re[This is a long profile of Boston’s hustling, tough-as-nails, young center Dave Cowens leaving a mark on the NBA during his third pro season. The article, which ran in the May 1973 issue of SPORT Magazine, is from the accomplished journalist Jeff Greenfield, now in his 80s and who has just about done it all in his writing career. Though the “unflamboyant” Cowens proves to be a tough nut to crack (he’s not really one to bare his soul, just his snap judgments of right and wrong), Greenfield offers some good historical background on the Celtics and basketball-indifferent Boston in the 1960s. If you stick with the story, you’ll gain a nice snapshot of the era and the reemerging Celtics, post Bill Russell. But first, how about a vision of Cowens soaring over Wilt Chamberlain, meeting his demise on a basketball rim, and popular murmur? That’s where we begin. Kind of funky.]

****

I know how Dave Cowens is going to die.

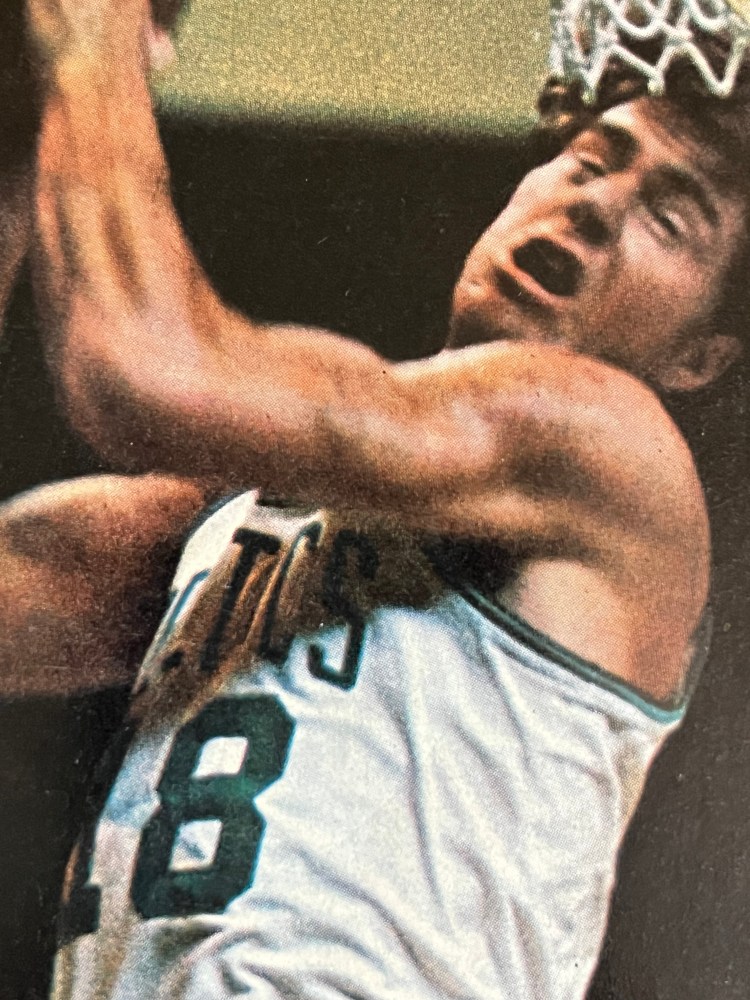

It is sometime in the future, the fourth quarter of the seventh game of the National Basketball Association playoff series; say, Boston against Los Angeles, a tight game. The Celtics are on the fence. Cowens, ranging far from the basket, is harassing the guards, then moving back to battle Wilt Chamberlain. With a split second of freedom, Gail Goodrich moves behind a screen and shoots.

Suddenly, Cowens leaps far above the five-inch-taller Chamberlain and slams the shot away. Before his feet come back to the floor, he is turning, moving toward the ball. His red hair flying, his mouth agape with effort, Cowens takes the ball the length of the court, twists himself into the air, stuffs the ball through the hoop—and on the way down hangs himself on the rim of the basket.

Given the insatiable appetite of sportswriters and fans for the heroic gesture, it is possible to imagine a quasi-religious cult emerging from such a glorious demise. Perhaps teammates would begin murmuring, “Cowens Died for Our Sins,” Or the Boston crowd, before each game, would recite chants spun from the cliches that surround Dave Cowens.

“He came to play.”

“Amen.”

“He plays both ends of the court.”

“Amen.”

“He puts out 100 percent at all times.”

“Amen.”

“Aggressive, a hustler.”

“Amen.”

****

Whether Dave Cowens becomes the Martyr of Boston Garden is best left to fantasy. Reality is remarkable enough. At the age of 24, and only his third year as a Celtic, Cowens has already:

- Led Boston to one of the best won-lost records in NBA history.

- Established himself as a leading contender for the Most-Valuable-Player award.

- Helped the Celtics draw the greatest attendance in their history, perhaps permanently, destroying Boston’s traditional indifference to professional basketball.

- Won the Most-Valuable-Player award in the East-West All-Star game.

- Outplayed, at one time or another, every other center in the league.

- And perhaps—just perhaps—suggested a reshaping of pro basketball as fundamental as the change generated by the “big-man” centers, Bill Russell and Chamberlain, 15 years ago.

The easiest thing to write about Cowens is that he runs all the time, with untiring effort, fighting, scrapping, ball-hawking, rebounding. Sportswriters frequently call Cowens a six-foot-eight John Havlicek or compare him with New York Knick forward Dave DeBusschere, Havlicek and DeBusschere being veterans who seem biologically incapable of relaxation on the court.

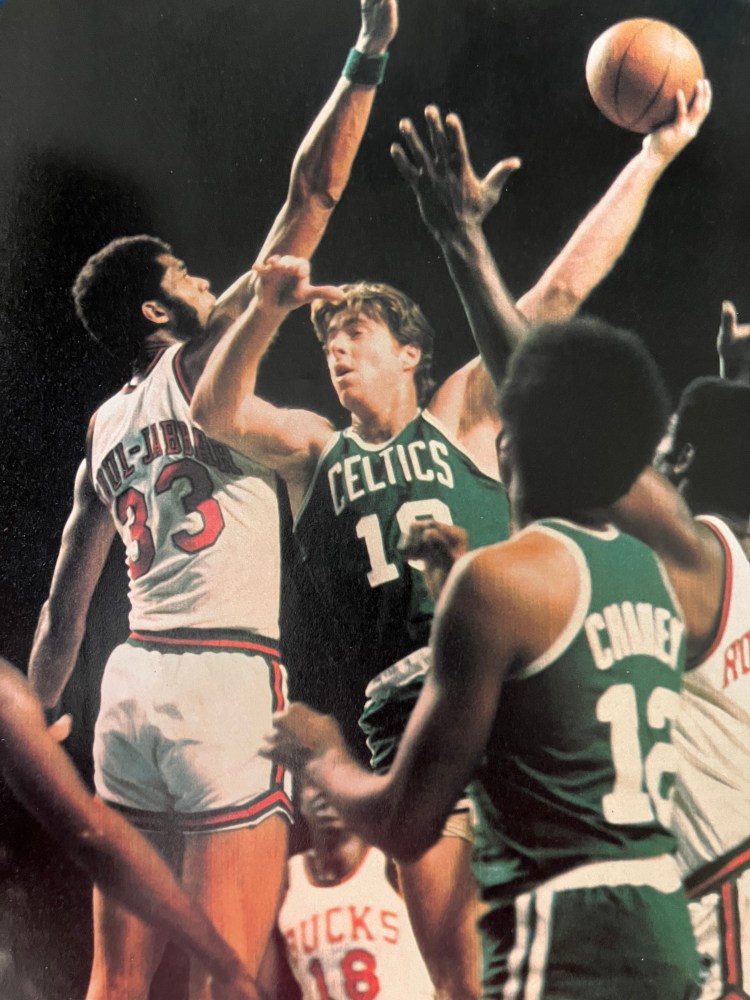

Yet there is much more to Dave Cowens than simply effort. It is that his attitude is fused with a remarkable breadth of skills. When you watch a ballplayer, over a period of a few weeks outrun Calvin Murphy, outmuscle Willis Reed, steal the ball from Walt Frazier, out-hook Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and out-rebound Wilt Chamberlain, you are not talking about sheer hustle. You’re talking about achievement. And while it is foolhardy to say that Cowens is now the best center in basketball, it is fair to say that no other center does as many things as well as Dave Cowens.

A team does not go into the final stretch of the NBA season with an .800 record on willpower; it is Cowens’ ability, linked to the near-lethal pace of his play, that has made the Celtics into a top team in less than three years after their sudden drop from championship to mediocrity.

“Dave Cowens is the most-improved player on the Celtics,” says Los Angeles Laker Jerry West. “He’s made the difference on defense with blocked shots and aggressiveness.”

“He does everything a ballplayer can do,” says the Knicks’ Jerry Lucas. “You can’t ask anything more of a player than what Cowens gives you.”

“He’s six-eight, but he jumps as well as the bigger guys,” comments Havlicek.

“Dave does something [Bill] Russell couldn’t do,” says Sam Jones, who helped make the earlier Celtics the greatest team in professional sports history. “He can come outside and shoot.”

A rebounder, a shooter, an intimidator on defense—what is Cowens’ unique gift? The answer, I think, is that there is none. It is the unique mix that makes Cowens remarkable. The statistics tell you that, with more than 20 points and just under 17 rebounds a game, he’s one of the top 20 scorers and top five rebounders in the NBA. But to watch Cowens display his range of skills tells you far more than a sheet of paper.

Not long ago, Boston played the Houston Rockets, who had just beaten the Knicks and the Milwaukee Bucks back-to-back under a new coach, Johnny Eagan. If ever a team figured to be. “up” for a game, it was Houston. Within the first quarter of that contest, Cowens:

- Hit a one-hander from 20 feet.

- Grabbed a rebound and threw a pass half the length of the court, triggering a three-point play.

- Slapped the ball away from Jack Marin, raced with the fastbreak downcourt and hit a running jump shot from the top of the key.

- Switched on defense and stole the ball from Calvin Murphy to set up another fastbreak.

- Crashed the boards for a rebound, then threw the ball the full length of the court to Havlicek for a layup.

By the time the quarter ended, Boston led, 47-24. Before the one-sided game ended, Cowens also hit hook shots from 16 and 18 feet, a 22-foot one-hander, a tip-in off a Paul Silas miss, plus a few spectacular baskets. Apart from these specifics, there is also Dave’s ferocious defensive play. Celtic guard Jo Jo White describes the impact of Cowens when the other team has the ball:

“Cowens is unbelievably quick for a center. When he comes out, he’ll switch and put his hand way out. With lots of centers—Wilt and Jabbar, for instance—they don’t like to come way out. They’ll move a little bit and then sag right back. So, all you have to do is hesitate, wait for them to drop back, and then move around the screen and shoot.

“With Dave,” White says with a smile, “a guard really doesn’t want any part of that monster shouting at him and waving his arm. They want to pick up the ball and get rid of it. And that gives you a chance to knock it away and run a break. We break with five guys—most teams break with two or three. If you’re a center, you don’t want to spend all day running up and down the court with Dave.”

“He’s super-quick,” says Celtic coach Tommy Heinsohn. “He’s almost a throwback to the days when there was no big man in the pivot.”

****

There is a special fascination in watching Cowens play basketball. He is constantly prowling the court, his eyes darting from center to ballhandler and back again, now skipping out to break up the flow of an offense, now crashing the boards for an impossible rebound, now driving around a momentarily sleepy defensive player, now stretching himself full length to pop a one-handed shot. He is a living demonstration of Newton’s first law: A body in motion tends to remain in motion. Cowens occasionally defies Newton’s better-known law, the one about gravity.

Yet Cowens is no superman. He is capable of nights of bad shooting, several games of bad play. He does not always win “the big one”; in the 1972 playoffs against the Knicks, and in a crucial week and series at the end of January against New York, Dave was outplayed by both Willis Reed and Jerry Lucas.

What he is is an extraordinarily gifted player whose skills are exactly matched with the style of his team; a quiet, unflamboyant individual who is utterly determined never to lose; and a performer who is helping to accomplish what once would have seemed impossible: Making basketball a first-rank sport in the hockey-crazed city of Boston, Massachusetts.

****

There were no ruffles and flourishes when Dave Cowens signed a three-year contract with the Celtics in 1970. Boston had just finished its worst year of basketball in memory; in the first year after player-coach Bill Russell retired, the Celtics posted a sixth-place, 34-48 record. For the first time in 20 years, the perennial champions had not even made the playoffs.

As for Cowens, his outstanding play at Florida State University—an 18.9 scoring average, a .519 shooting percentage, and a million rebounds—went largely unheralded by the national press, because the school was on NCAA probation and did not play in the publicity-drawing postseason tournaments.

Nor did Cowens have any press build-up as a high school player. This is perfectly reasonable, since he did not begin playing high school basketball until his junior year, preferring baseball and swimming (he competed in the 100-yard backstroke and the 200-yard freestyle).

But in the summer between his sophomore and junior years, his growth from a six-footer to six-foot-five in the presence of a new coach persuaded Dave to try basketball. He was good enough in his senior year to bring Newport (Kentucky) Catholic High School to the state championship tournament and to win a scholarship to Florida State.

“We played a fastbreak, pressing-defense game,” Cowens recalled. “I’d go from harassing an inbounds pass to picking up the ballhandler to running back to halfcourt. It’s the only way I’ve ever played basketball, and the only way I like to play.”

It is also the way Celtic general manager Red Auerbach likes his teams to play. He scouted Cowens personally and signed him to a three-year contract. (It expires this year, at which time Cowens will be in the strongest bargaining position since General Grant.) Auerbach’s original plan was to use Cowens as a forward, or as a temporary center until a permanent replacement for Russell could be found. It seemed logical, since Cowens had played both facing and with his back to the basket. But after watching Cowens’ strength and jumping, Auerbach and Heinsohn changed their minds.

“There was the matter of his attitude,” Auerbach recalls. “You could see that nobody was going to tell this kid he couldn’t do something if he wanted to do it, and Cowens obviously wanted to play center.”

He proved his intentions—and his capacity to make good on those intentions—even before the start of his rookie season. At the annual Maurice Stokes Memorial game at Kutsher’s resort in the summer of 1970, Cowens scored 32 points and was voted the game’s most valuable player.

He averaged 17 points and 15 rebounds a game in his rookie season (seventh in the NBA in rebounds) and tied with Geoff Petrie of Portland for Rookie of the Year honors. More important, the Celtics finished with a 44-38 record in the 1970-71 season, although that record meant only a third-place finish and no spot in the playoffs.

There were also frustrations and lessons to be learned. “I had an attitude, a feeling I never was a shooter, I couldn’t shoot a lick,” Cowens said. “So I’d have a shot and wouldn’t take it. My teammates told me, ‘You’ve got to shoot. It’ll come. You miss 10 in a row, you’ll make it up.’ It was something I had to learn.

“But you’re learning all the time. That first year, I remember one game when Gus Johnson just took me to the cleaners. I’d come out, he’d drove right by me. I’d hang back, he’d shoot over me. It’s just things you learn.”

****

Cowens was also learning that the NBA officials tend to look with suspicion on a rookie’s aggressiveness. He was called for 350 personal fouls (tops in the NBA) and fouled out in 15 games (second highest). He continued his whistle-baiting play into his second season, drawing 314 fouls and fouling out 10 times. This was, however, not the only bit of consistency in Cowens’ 1971-72 performance. He increased his scoring average to 18.8 points, increased his field-goal percentage to .484 and won himself a berth on the East All-Star team, where he scored 14 points and got 20 rebounds.

Once again, however, it was what happened to the Celtics that highlighted Cowens’ value. They finished with a 56-26 mark and first place in the NBA’s Atlantic Division. Then, in the playoffs, Boston beat Atlanta in six games before losing to the Knicks in five.

“Dave simply did not have a good series,” recalls a member of the Celtics’ family. “Lucas was shooting—and hitting—from 20 to 25 feet out, and Dave did not have the option of coming out from the low post or switching.”

Despite the loss to the Knicks, the Celtics were back as contenders—and Cowens had established himself, after only two years in the league, as an outstanding player. Apart from the season’s statistics, there were several outstanding individual games: 37 points against the Milwaukee Bucks, the All-Star game in which he blocked two shots by Jabbar and tied the game with 10 seconds to go (Jerry West won it for the West with a shot at the buzzer), 32 points and 21 rebounds against Baltimore, 26 points and 20 rebounds to eliminate Atlanta for the playoffs, and a 23-point, 16-rebound performance in the Celtics’ only playoff win against New York.

In the summer of 1972, the Celtics made a trade that helped turn Cowens from very good to superstar: They gave the rights to Charlie Scott to Phoenix for Paul Silas, a 29-year-old, six-foot-seven forward with a rebounding average of 12 per game. Silas became the “sixth man” of the Celtic offense—a job John Havlicek had held for years—coming in for starter Don Nelson. The acquisition meant that Cowens did not have to handle the rebounding chores on his own.

“Silas took some of the rebounding pressure off Dave,” Coach Heinsohn says, “and you see that on defense. But it also let Cowens move out further on offense, and with his outside shooting getting better, it gives our whole offense more variety.”

“Basically,” says Cowens, “Paul gives me the chance to freelance more. It makes it easier for me to play the kind of game I like to play.”

This season has been the kind of season the Celtics like, the kind they have not seen since the days of Russell. They won 40 of the first 47 games, doing it with the classic Boston pattern: running the other team into the ground. The Celtics are a team of opportunity. They prefer to score off a fastbreak, rather than by moving their men in a pattern offense as the Knicks do. This requires, among other things, a defense that makes its opportunities, by stealing, knocking the ball away, and rebounding consistently off the defensive boards.

With John Havlicek, the Celtics have a consistent high scorer; with Chaney and White, they have a good shooter and ballhandlers at the guards. What makes them different is that their center runs. Opposing big men who are used to taking an occasional breather by hanging back after a fastbreak starts will not find Cowens keeping them company.

This means that the Celtics have a number of advantages: an extra rebounder on the offensive boards if the shot off the fastbreak does not go; another outside shooter, if the fastbreak is shut off; and a most disheartening influence on the opposing center, who has the choice of either running with Cowens or feeling like a man on the sixth day of a five-day deodorant pad. (In Boston’s 120-96 win over the Milwaukee Bucks in February, Cowens twice left Jabbar flatfooted and took the ball the length of the court for baskets.)

By running—and winning—the Boston Celtics with Dave Cowens are simply keeping faith with a long-standing Celtic tradition, going back to the days of Cousy, Russell, Sharman, Heinsohn, and then-coach Auerbach. There is, however, a difference that is starting to emerge. The current Celtics have more of one thing than their illustrious predecessors: fans.

To understand how significant this is, you have to understand the strange legacy of the Celtics and the curious role played by perhaps the greatest basketball player who ever lived: William F. Russell.

****

The Celtics are a bittersweet fusion of triumph and frustration. As a sports franchise, they are the greatest artistic success in the history of professional sports. From the time, Bill Russell returned from the 1956 Olympics and joined Boston in midseason, to the time he retired as player-coach in 1969, the Celtics won 11 NBA championships in 13 years. They won eight of those championships in a row; nine years in a row, they won their division championship.

There is nothing like that record. The Montréal Canadiens of the late 1950s, the Green Bay Packers of the 1960s, the New York Yankees of the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s, all were supreme in their sports. None of those teams could win eight-straight championships.

And yet, the Fates have seen fit to place the extraordinary Celtic team in a city whose residents seem to see basketball as something to watch while waiting for the ice to freeze. The greatest basketball dynasty plays in a city that really does not care all that much about basketball. It is an ironic mismatch, as if Bobby Fischer toiled in a society that worshipped backgammon, or as if Mark Spitz lived in a land that abhorred both water sports and money lust.

You can see this indifference graphically in the bookstore of North Station, of which the ancient Boston Garden is a part. There are endless books on hockey; the Boston Bruins books alone, fill a shelf. There is exactly one book by, on, or about a Celtic: a seven-year-old autobiography by Bill Russell. More important, you can look at the attendance figures. The Boston Bruins have always been the toughest ticket in town, whether they were the doormat of the National Hockey League or Stanley Cup contenders. Even the minor-league hockey Boston Braves pack them in.

****

And the Celtics? In Russell’s first-year, 1956-57, the Celtics averaged 10,500 per game. Only once since then has the attendance averaged over 10,000. (The Garden holds 15,315 for basketball games). All through the great Celtic years, Boston drew between 7,000 and 8,500 people per game. In 1961-62, the year they won the fourth of their eight-straight championships, they averaged barely 6,600 per game. Even playoff games in those championship seasons were sometimes played in front of empty seats.

“This is a hockey town,” says Richard Goodwin, the former White House assistant. “The only basketball enthusiasm I can remember around here is during the Cousy and Heinsohn eras at Holy Cross. This city gets cold in the winter; the kids are on skates when they’re five years old, and instead of basketball leagues, they’re playing hockey. Go to the arenas in Boston. You’ll find pee-wee hockey leagues practicing 24 hours a day.”

“There is no basketball heritage at all in Boston,” says Johnny Most, the radio voice of the Celtics for 20 years. “A lot of major high schools never even played basketball when I came to Boston. And pro ball only started up in the late 1940s, while you had baseball and hockey here forever. You contrast that with New York City, where the high schools and colleges always had strong teams. So, our fans are college kids today, who were just born when the Celtic era started. We don’t have that many 50-year-olds fans.”

Then there is Red Auerbach’s “128” theory—the idea that the Boston area’s basketball fans live out in the suburbs, beyond Route 128, while the hockey fans are the blue-collar, white working people who live within the city and find the journey to the Gothic horror of Boston Garden less of a burden.

And finally, perhaps the most-complicated issue: That of race and the impact of Bill Russell.

Boston has, for a large Eastern city, a small Black population. Its sportsfan population is overwhelmingly white. It was here that Bill Russell came—17 years ago by the calendar, light years away from now in attitude. It was a time when Blacks were Negroes, when sports were still bathed in illusions, when the pressures of the outside world seemed not to intrude into the locker room. It was also a time when Black athletes south of the Mason-Dixon line were expected to eat and sleep in segregated quarters and not to complain about it.

Bill Russell was not that kind of man. He believed—with reason—that a racial quota existed in basketball, and he said so. He believed that a proud man did not accept bigotry—and he said so.

“Good ballplayer, I’ll give him that,” a Celtic rooter says. “But as a man—” he waves his hands. “Didn’t like whites.”

“Guys like Russell,” says a cab driver. “They get to the top, and they think they’re God.”

Now, by accident of fate, many of the obstacles between the team and their fans are gone. Cowens is white, red-haired, and familiar. (“He’s not Irish, but people think he is,” grins a Celtic official.) The fans have tasted the defeat which makes victory more desirable. A new generation of fans has seen basketball on network television. And they are coming to the Garden. The Celtics will, in all probability, set an attendance record this year, and the construction of a new arena, designed to accommodate rather than the tolerate basketball, will soon begin.

Thus, the Era of Cowens seems, for a host of reasons, to be coinciding with an Era of Good Feeling between Boston and the Celtics. And Dave Cowens is both a cause and a beneficiary of this popularity.

****

A conversation with Dave Cowens is not an exercise in self-revelation. It is not a seminar in political philosophy or the building of a financial empire. It is a talk with a young man who cares intensely about basketball, about winning, about achieving what he sets out to do, and about preserving his own privacy from an increasingly curious world.

Cowens, remember, is in a position few of us ever find ourselves in. He is in a profession whose best practitioners achieve their best performances, and their highest acclaim, at an age when most people have only a vague idea of what they want to do with their lives. The slow, steady path from novice to success is a matter of months, not years or decades. Cowens is also in a job where strangers flock around him while he is undressed, asking whether he expects to do a good job and then ask him why he did or did not do the job he wanted to do.

Imagine this in your own life: You are putting on your socks, and 13 people with notebooks, microphones, and tape recorders are pushing around you.

“Herb, you’re trying to negotiate a big sale today with Consolidated Widgets. Last time you didn’t get the order you hoped for. What are you going to do differently?”

“Herb, is Mr. Blodgett the toughest boss you ever worked for? How do you compare him with Mr. Firkins?”

****

By its nature, Dave Cowens’ job is an interesting one; yet when we talked, the interest was painful for Cowens to reflect on. We were in a snack bar in the bowels of LaGuardia airport late on a Saturday night, waiting for a 1 a.m. plane to take the Celtics and the Knicks up to Boston for their second meeting in 19 hours. Barely an hour before, Boston had lost to New York 111-108, in a brutal, hard-fought game in which no team ever led by more than seven points. Cowens had scored 21 points and gone 9-for-18 from the floor, but he brought down 11 rebounds instead of 16 or 17. Further, the Celtics’ fastbreak was completely shut off in the fourth quarter: Not a single point was scored off a Boston break in the last period.

“I take a lot of responsibility for losing,” Cowens said over a meal of sandwiches, pre-cooked, French fries, and a milkshake. (The glamorous world of professional athletics gets a lot less glamorous around midnight in a deserted airport.) I should have got 10 more rebounds . . . the amount of time I played . . .” He shook his head.

“Yeah, but doesn’t it make any difference that the last time you played New York, you got 38 points and 21 rebounds?” I asked.

“No,” Cowens said quickly. “You can’t play one good game and one bad one.”

“All right. But you guys have won more than 80 percent of your games. You keep this up, and you’ll have one of the best records in NBA history.”

“I don’t understand that kind of thinking,” he said. “I don’t want to lose any games. If I say to myself, ‘We’ll win 60,’ we’ll probably win 40. You have to set that goal as high as possible. I know that sooner or later, we’re going to lose, but I don’t expect to lose any games. Do you think it makes sense to go out and say, ‘Well, maybe we’ll lose tonight, but that’s okay, we have to lose sooner or later?’ Doesn’t make any sense to me.”

“Do you mean,” I asked Cowens, “if you found yourself on the [then losing] Philadelphia 76ers, you’d expect to win all the time?”

Cowens nodded. “If I woke up in Philadelphia, I’d say, well, I better learn about what Mr. Carter does, and how Mr. Loughery plays. You have to learn to complement your teammates. Then if I found anybody on the team who wasn’t doing his job, I’d hope we got rid of him. We get paid well enough to put out.

“I have a very simple notion of how you win,” Cowens said. “If you go out and hustle all the time, and you’ve got good people around you, you’re going to win. The most games I ever lost in a college or high school season was nine. We always won more than we lost. I just can’t see myself on the losing team.”

A few minutes later, we crowded into the coach cabin of a packed flight to Boston. The NBA Players Association has demanded—and won—first-class seating for all flights lasting more than an hour. The flight to Boston is 50 minutes, and the Celtics have had too many management and money problems to disregard those costly 10 minutes. Consequently, the Celtics rode in back while the prosperous New York Knickerbockers rode the same plane in the first-class cabin. Celtic general manager Red Auerbach rode up front, too.

I asked Cowens about writers—and what they don’t understand about the game. “The things they least understand,” he said, “are the subtle things that don’t have anything to do with where the ball is. It’s tough for anyone to understand who hasn’t played. You might be on the other side of the court, but you’ll be reacting, thinking, and what you do may have a lot to do with the basket—even if you never get to touch the ball. No one can really appreciate that except your own teammates.

“I think I know better than anyone else how I’m doing. I know I’m going to make mistakes, but you don’t say, ‘Oh, I lost, I’m depressed.’ You say, ‘I’m not going to do that again.’ That’s what’s really important. Is setting a record that important? Is getting the MVP for an all-star game that important?”

The next afternoon, in Boston, I watched Cowens come to grips again with the thing he hates most—losing. In the second quarter, the Knicks beat the Celtics’ brains in—and Willis Reed, who had suffered so badly at the hands of Cowens in November, hit seven of eight shots from the floor, inside and outside, to lead New York to a 53-40 halftime lead. The Celtics’ fastbreak was completely shut off; and Cowens did not score a point in the second quarter, missing on drives, outside shots, and hooks. For the first half, he hit only 2-of-12 (as a team, Boston hit only 30 percent of its shots in the first half).

Then, in the second half, Boston took advantage of a sudden Knick cold spell and began to come back. Cowens hit from 17 feet, then from the top of the key. With about three minutes left in the game, Dave fed Havlicek for a backdoor layup, and the score was 86-85. Boston got no closer and lost to New York, 96-93. Cowens went 7-for-21 from the floor, winding up with 19 points and 14 rebounds.

****

After the game, Cowens sat in the trainer’s room, on a table, a towel wrapped around him. He was cordial, but there is something about losing that cuts Cowens to the core. In another kind of personality, it could lead to a strong sense of depression. In Cowens’ case, it led to a brief slump after which he helped to beat the Lakers, destroy the Bucks, and keep Boston in first place. Not liking to lose is one thing. Doing something about it is another.

For Cowens, the future in basketball seems unclouded. Outside of basketball, the future is—so far—simply uninteresting. Money does not appear to be the most-important thing in his life. He lives in a converted bathhouse in Weston, Massachusetts, and the visual symbols of wealth— clothes, cars, luxury—don’t engage him. “He’s not one of your greedy, weirdo athletes,” a teammate says. “He’s more like somebody you grew up with.”) Apart from a basketball, camp and speaking engagements, he has no business dreams so far.

“I could never work behind a desk,” says Cowens, who spent part of one season, taking courses in automotive mechanics. “I have to work with my hands.” He needs the peace and quiet of the country.

“I hate cities,” Cowens declares, his voice for the first time taking on the tinge of his Kentucky origin. “I don’ like con-crete. I don’ like cee-ment.”

He is someone doing what he likes to do, and doing it very well. “There’s a pharmacologist I know,” Cowens reflected. “He’s in research. I told him, ‘I like to be doing something good, something worthwhile like you are.’ The guy said to me, ‘I take my kids to the Garden. We watch you. We root for the Celtics. We’re close to each other. That’s doing good too.’”

For a new generation of basketball fans, Cowens is doing a whole lot of good. It is likely to be a fact of life in the NBA until the day when Cowens goes up for that last lethal basket.