[Pro athletes, like Hollywood stars, have long been the subjects of wild “read-all-about-it” headlines in the American tabloid press. From Way Downtown generally doesn’t scrape the bottom of the barrel for copy. But some of the tabloid stories of yore, with their wild conspiracy theories, are fun to revisit after all these years.

Take this stop-the-presses “plot” pulled from the April 1971 issue of the magazine Sports Today. Larry Bortstein, a very respected NBA scribe at the time, makes the case that the NBA powers- that-be secretly plotted to turn the expansion Milwaukee Bucks into an overnight NBA title contender. It’s an interesting theory, and Borstein tracks a few trades and a major hiring to make some interesting connections by association.

Ironically, his speculation doesn’t go far enough. Mainly because Bortstein doesn’t chase the right question. It is: Why would the NBA want expansion Milwaukee to win it all so quickly? Putting on my 1970s tabloid editor’s hat, the answer is rooted in the NBA’s then-addiction to expansion. The divvied-up expansion fees subsidized many a struggling NBA franchise through a difficult decade with its rising costs and saturated big-city sports markets.

For the new owners, however, their million-dollar-plus plunges into big-league basketball bought them shoddy rosters and losing ballclubs. According to NBA projections, the blowouts would last on average for five years or more before an expansion team became competitive. For many remorseful expansion owners and prospective NBA investors, the question became: Why buy into a such a losing proposition? It didn’t reflect well on their business acumen at the arena and among their pals at the country club.

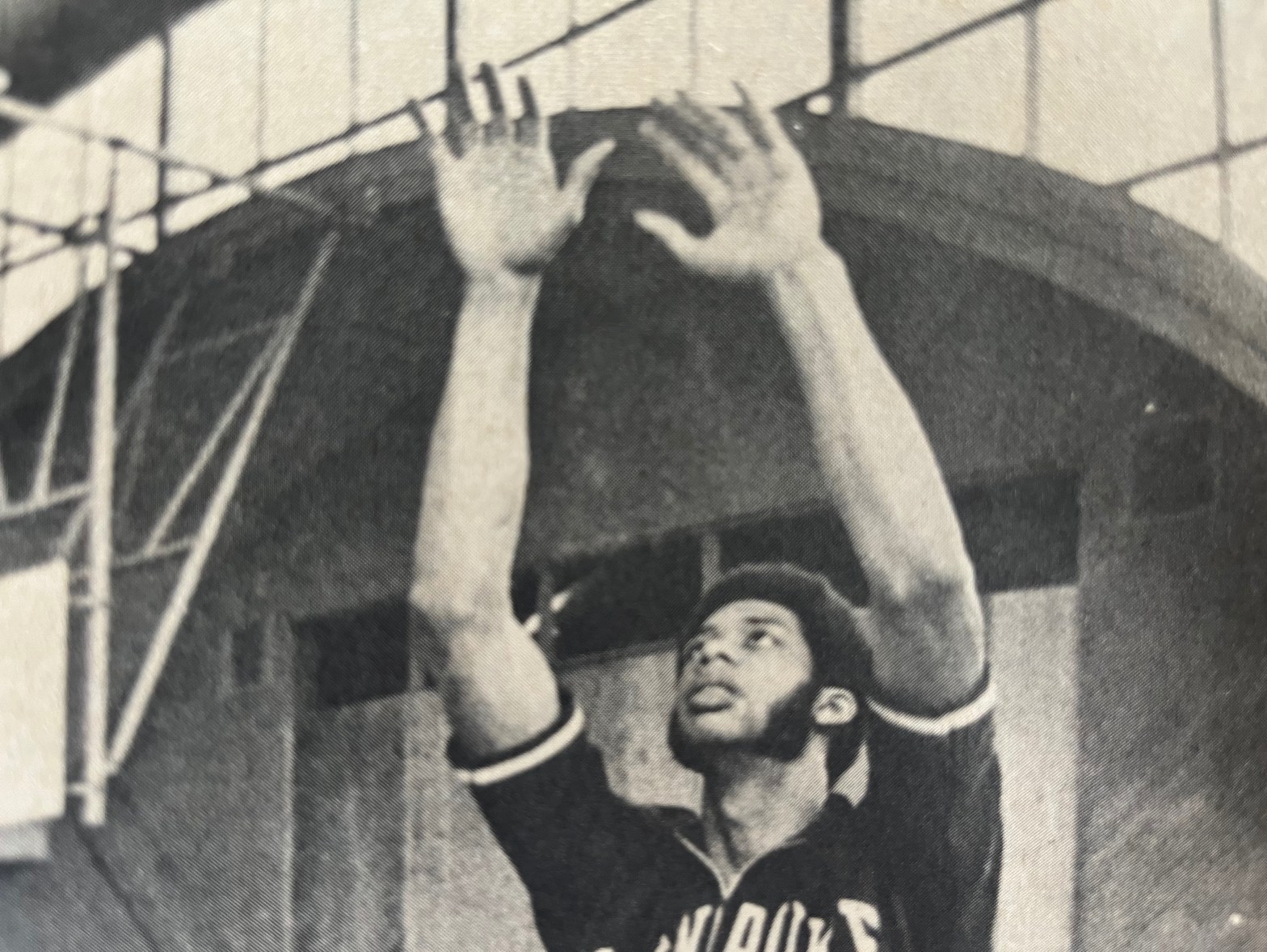

To stop the chatter, the NBA needed an expansion team in the winner’s circle. Milwaukee lucked into drafting (and signing) Lew Alcindor, pro basketball’s next seven-foot superstar, and the NBA needed to surround him with a veteran superstar or two to put the Bucks in the winner”s circle. Ergo, Oscar Robertson landed in Milwaukee.

I can’t prove my above narrative. I’m just going for the sensational, riffing off what I know thematically about the 1970s NBA, and offering some big-picture background as you dive in Bortstein’s sensational piece. So, here’s the article, the cover story for a Sports Today issue that included stories titled, “I Saw Willie Mays Hit All 628 Home Runs,” Agony of a Baseball Gypsy,” and “The Sleepness Nights of an NHL Goalie.” ]

****

The phone rang in the City Hall Building office of Boston’s recreation director. A large man rushed down the corridor, reached across a desk, and picked up the receiver.

The call was from the NBA’s Milwaukee franchise. The large man had spent his final season as a player with the Bucks two years earlier. He had helped the expansion franchise get off to a relatively smooth beginning in the hotly competitive NBA. The man on the other end of the phone hadn’t forgotten.

“Wayne,” the man in Milwaukee said. “How’d you like to come back out here and work in our front office?”

The big man in Boston was impressed and flattered. He had hoped to obtain an executive position with a professional basketball team since he quit playing. However, the closest he came to another link with the sport was as a commentator during broadcasts of Celtic games and as the head of the city’s recreation program.

Apparently sensing a receptive response, the man in Milwaukee spoke again. “Besides,” he said, “we think we can get Oscar to come with us if you’re involved.”

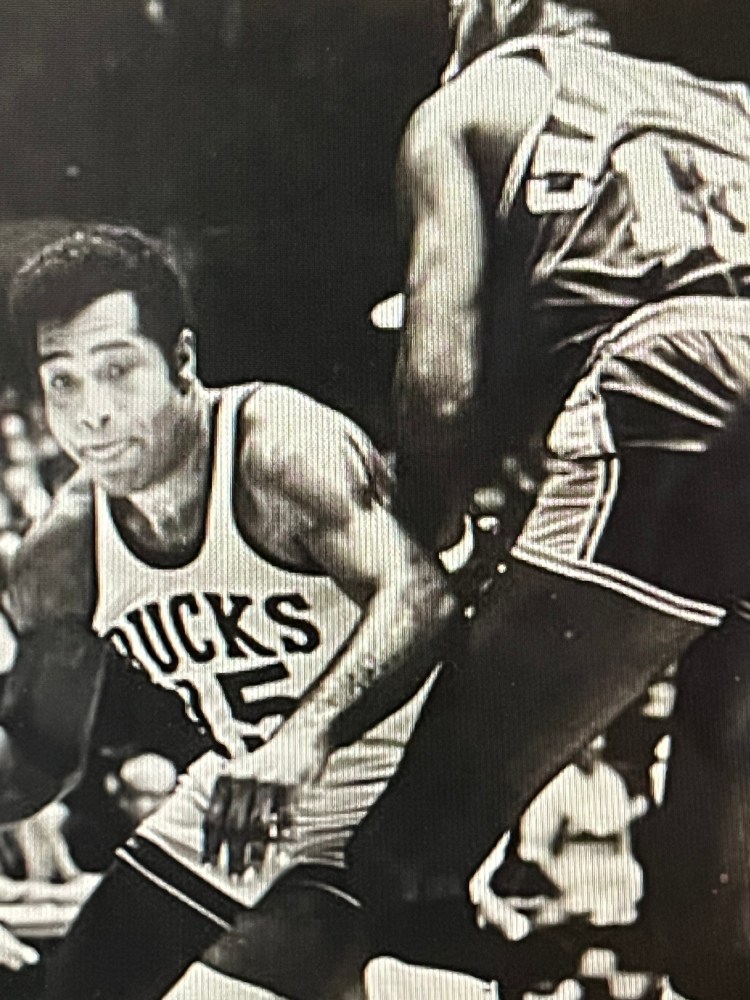

That’s how Ray Patterson, president of the Bucks, persuaded Wayne Embry, the team’s captain and center in its first year, to return to Wisconsin. And subsequently, that’s how Oscar Robertson, the greatest playmaking guard in NBA history, was persuaded by Embry to join Lew Alcindor and the Bucks.

A number of other teams had been seeking to obtain the Big O following his dispute with the management of the Cincinnati Royals. The reunion of Robertson and Embry, two of the key players on Cincinnati’s contending teams of the early 1960s, is just one of the significant, largely unnoticed, pieces of evidence pointing to the possibility of a plot to fashion an NBA championship for the Bucks this season.

The Bucks’ management was very anxious to coax Robertson into the Milwaukee fold. Oscar had long considered Embry one of his closest friends in basketball. The 6-8 Embry felt the same way about Robertson, attributing much of his success as a wide, rather slow, NBA pivotman to Oscar’s slick ballhandling.

“Oscar made me a better ballplayer,” Wayne says. “I was averaging 10 points when he joined the Royals in 1961. After he came, my average went up to 18 or 20. He is the greatest of them all.”

Embry’s closeness to Robertson was needed by the Bucks, who feared that the Big O would agree to join another club in the NBA. Robertson, who had a clause in his contract granting him the privilege of selecting the team to which she would be traded, was considering the New York Knicks, the Phoenix Suns, and even the ABA Indiana Pacers, based in Indianapolis where Oscar grew up. The previous season, he rejected a trade that would have sent him to Baltimore.

Wayne sought out Robertson to offer advice. “He told me,” recalls Oscar, “that the Milwaukee organization was the best he had ever seen in basketball. Everyone thought I was just after more money. The finances were important, of course, but I wanted to know the organizational structure of the club and the general situation. After going through a year like I had in Cincinnati, I had to know more about the team I was going to play for than the names of the other guys on the club. Wayne’s advice clinched the decision for me to come to Milwaukee.”

Embry is now administrative assistant in charge of player development for the Bucks, and he will direct the club’s selection of college draft choices in the spring. Launching a long winning streak earlier this season to take command of the NBA’s Midwest Division race, the Bucks employed a set lineup. Since they figure to be one of the last teams to choose in this year’s college draft, they will not obtain one of the top prospects. But Embry already has earned his season’s salary for his role in bringing Robertson to the ballclub.

But the plot to bring the Bucks a title goes deeper than the Embry-Robertson case. The Bucks called attention to it themselves by making their controversial trade of Bob Boozer and Lucius Allen appear even more controversial.

During the training season, Milwaukee sent Don Smith, a reserve forward and rebounding specialist, to Seattle for Boozer, a veteran forward, and Allen, a sophomore guard. On the surface, the Bucks seemed to get a far better deal, receiving two players of proven worth for one who played infrequently during NBA stops in Cincinnati and Milwaukee. Many people wondered how come.

Then Walter Kennedy, the NBA commissioner, revealed he had levied “substantial fines” against both Milwaukee and Seattle for failing to follow proper procedure. This procedure, explained Kennedy, had been outlined the previous year in a new rule handed down from league headquarters.

The rule stipulates that a conference phone call must be held between representatives of both teams and the commissioner’s office before a trade can be consummated. No other sport has such a ruling, and the Bucks and Sonics were the first teams held in violation of the NBA dictate.

However, the feeling persisted among knowledgeable NBA observers that there remained a hint of conspiracy in the air, because Boozer was a close friend of Robertson’s and Allen was one of Alcindor’s very closest buddies.

Boozer entered the NBA with the Cincinnati Royals, the same year as Robertson, 1960-61, after they had been teammates on the United States Olympic team in Rome. An All-America at Kansas State, Boozer was not an immediate sensation as a pro, but by the 1963-64 season had become a key member of the Royal team that challenged Boston right down to the wire in the Eastern Division. However, midway through the season, Boozer was surprisingly traded to the New York Knickerbockers.

“Bob was just becoming a helluva player in the NBA,” recalls Robertson. “But the Royals always seemed to trade away players they felt were getting better, and who would eventually ask for more money the next season. There was no reason for trading him. With him, we could have had a championship team.”

Since being dealt from Cincinnati, Boozer played for New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Seattle, before finally rejoining Oscar in Milwaukee this season. He has never been a star, but has always been one of the finest outside shooters among NBA forwards. It is easy to see how the long-term relationship between Robertson and Boozer helps solidify the Milwaukee ballclub. Though they live at opposite ends of the city, the 11-year NBA veterans are among the closest teammates on the Bucks.

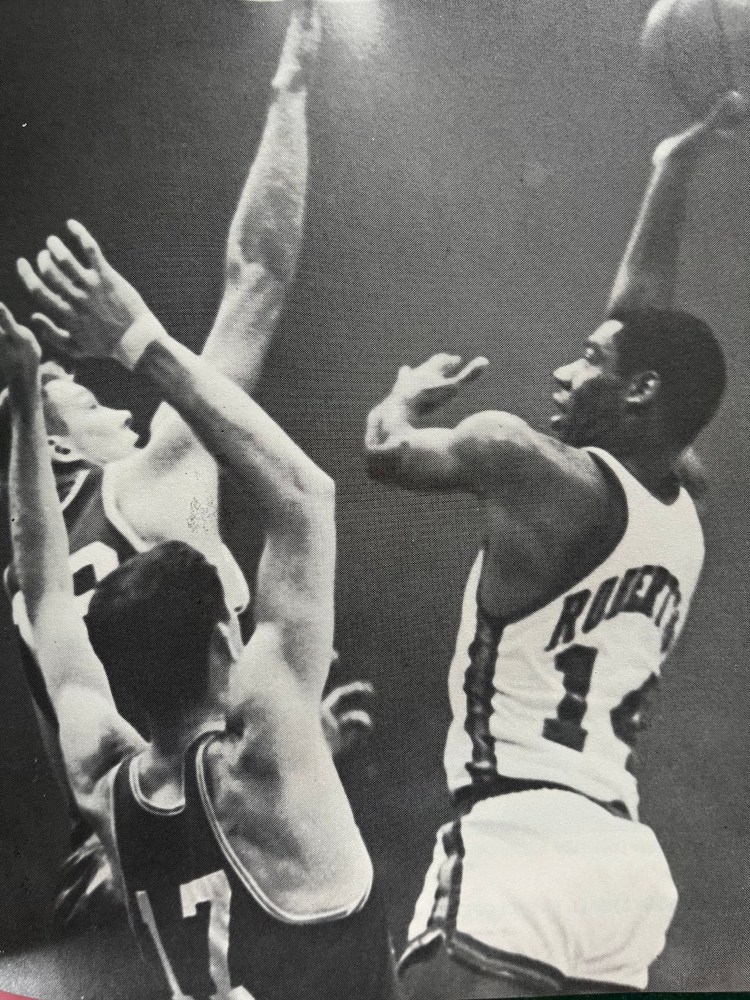

Allen is even closer to Alcindor. They were roommates on two UCLA collegiate championship teams. A product of Kansas City, Allen, who started this season as a regular then alternated between starting and coming off the bench, is the only member of the Bucks who calls Alcindor by his Islamic name, “Kareem.”

Smith’s story is clouded in doubt. He spent only three months with the Royals in 1968-69 before being traded to Milwaukee for Fred Hetzel. He seemed to answer the Bucks’ need for a strong rebounding forward, and served in that capacity last season inasmuch as Bob Dandridge and Greg Smith, the other Milwaukee frontliners, were smaller and better suited for a shooting and running game.

It has been alleged that during Smith’s short stay in Cincinnati, he was the target of Robertson’s sharp tongue. Oscar has been known to blast players who failed to hang onto his passes. During his years in Cincinnati, Boozer was supposed to have come in for much of this treatment.

But Smith apparently didn’t develop into the player Boozer became under the guidance of Robertson. And when it became obvious that the hostility between Smith and the Big O might be renewed if they were reunited as teammates this season, Smith was traded.

Aside from the strange cooperation, the Bucks have received from rival teams in these trades, there has been a suspicion held my some that Milwaukee has also been given the edge by the NBA itself.

The matter of the Bucks’ unusually light schedule during the early weeks of the season is a case in point. By November 15, with the season in its fifth week, Milwaukee had played only 10 games. By contrast, the Detroit Pistons had played a whirlwind schedule of 17 games, as had Phoenix, the Bucks’ main Midwest Division rivals. The Chicago Bulls, the fourth team in the league’s toughest division, had played 13.

There are other unanswered questions, reaching back to the early months of 1969. How, some people ask, did the Bucks sign Lew Alcindor when, by the giant center’s own admission, the offer made by the ABA’s New York Nets was more substantial. Rumors persist that a committee of prominent NBA people, Celtics’ general manager Red Auerbach among them, had received. Alcindor’s signature on an NBA contract long before his graduation from UCLA to assure his joining the older league.

After the Bucks’ first offer, a reported $1.4 million, topped the original offer of the Nets, the ABA people came back with a counteroffer. This one included part ownership of the New York franchise, a share in television and gate receipts, plus an outright cash bonus of $500,000. But Alcindor wouldn’t budge. He said he would consider only one offer, and he remained adamant in this decision. He accepted the Milwaukee offer without equivocation.

The man making the offer was Wes Pavalon, owner of the Bucks, a 36-year-old multimillionaire. “There’s nothing mysterious about paying tremendous salaries to tremendous athletes,” Pavalon insists, “or in making them happy in other ways.”

His other ways include taking the Bucks on a swing of exhibition games in Hawaii last September and regularly inviting his players and other staff members aboard his luxurious yacht. “Oscar feeds Lew, scores, takes a lot of pressure off Alcindor and helps the gate,” Pavalon points out. Although the Milwaukee Arena has a seating capacity of only slightly more than 10,000, the Bucks made a sizable profit last season. They grossed $1,208,700, and the net was $408,509. They also had the largest road attendance in the NBA, largely due, of course, to the fabulous rookie, Alcindor.

Without Alcindor, the Bucks in their first season, 1968-69, grossed only $558,400 and lost money. This season, with title talk still abounding, the gate receipts and enthusiasm are greater than ever.

Just good business? Or something more.