[In the late 1980s, Ben Yagoda spent his days as a Philadelphia free-lance writer (and former movie critic at the Philadelphia Daily News) who was working on a biography of the great American entertainer and popular cowboy philosopher, Will Rogers. The latter, like most biography projects, was a long slog and quest for more information and perspective. Yagoda hung in there, wrestling with the inherent difficulty of capturing a bygone hero.

But before publishing his first book and biography in 1993, Yagoda slipped in some freelance sports assignments. That included this piece about Mike Gminski, the new center of attention in Philadelphia 76er-land. Yagoda does a really nice job with this one, published in the November 1989 issue of the magazine Philly Sport. Enjoy!]

****

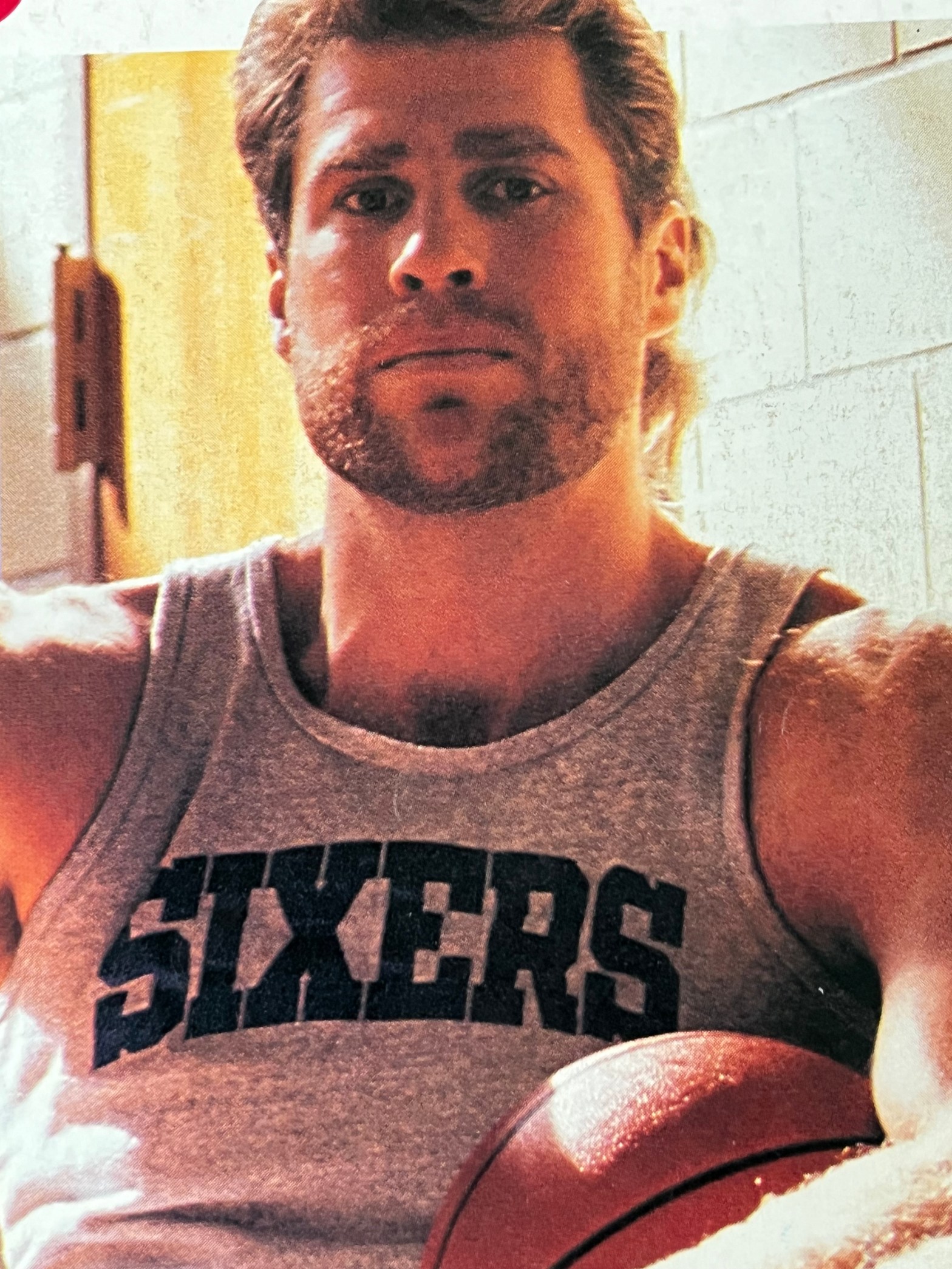

When Mike Gminski was an undergraduate at Duke, the student newspaper dubbed him “G-Man.” The moniker was perpetuated when the New Jersey Nets, his employer for 7 ½ NBA seasons, embroidered it on the back of his warm-up suit. (During the early years at New Jersey, Gminski was in his warm-up suit a lot, especially during games.)

Nobody who knows him actually calls him G-Man, although some friends shorten it to “G.” His Duke frat brothers all call him “Big Guy.” As the 6-11 Gminski points out, with his trademark dry humor, they’re an observant bunch.

But if Gminski didn’t have a nickname, a perfect one would be the first word of this paragraph.

But.

That’s because almost anytime anybody talks about Mike Gminski’s abilities as a basketball player, they eventually get around to using that word. This was glaringly apparent last March, when Gminski signed a five-year, $8.75 million contract with the 76ers that made him, after Moses Malone, the second-highest-paid player in the team’s history—higher than Charles, higher than Dr. J!

Sixers GM John Nash: “Mike is not flamboyant. He is not the weak-side defender that an Hakeem Olajuwon or a Patrick Ewing is. But if you check the statistics on blocked shots, you’ll see he is better than most.”

Elmer Smith in the Philadelphia Daily News: “He is not outstanding in any category except as a foul shooter. There is nothing about Gminski that inspires awe. But he is as reliable a rebounder and scorer as there is in the league today.”

Even Gminski gets into the act: “Even when I look at game films of myself, it doesn’t look like I’m doing a lot. But then you pick up the box score at the end of the night, and I’ve got 18 or 19 points, a couple of blocked shots, a few assists, and I’ve played good defense.”

Even worse was when Sixers coach Jimmy Lynam forgot the but: “I think because he’s not a great intimidator on defense, a lot of people don’t think that much of him. They’re just is not a wealth of talent available out there. We know what we’re going to get from him. He certainly is no liability on defense, and you’re going to get those 10 rebounds and 17 points.”

In all, there was so much back-handed complimenting going on that it seemed like a Wimbledon preview. But in fact, far from getting snookered, the Sixers were lucky to get the G-Man for the price they paid.

For starters, Gminski is considered a proficient, legitimate big man by those in the NBA inner circle. Second, there is a distinct shortage of proficient, legitimate big men in the NBA—and, after a couple of years of revisionism, the dominant thinking is once again that a winning team needs a proficient, legitimate big man.

Third, had Gminski not agreed to terms, he would have become an unrestricted free agent at the end of the 1988-89 season, meaning that he could sign with any team in the league—and he could have signed for extremely big bucks. This became apparent in the summer of 1988, when Danny Schayes, a center whose picture belongs in the dictionary next to the definition for “journeyman,” inked a six-year, $9 million pact with the Denver Nuggets. Says Gminski’s father, Joe: “When I read about that, I said to myself, ‘This is it for Mike.’”

Indeed, if Gminski had waited till the season was over to sign, he clearly could have gotten more. Lots more. In August, Atlanta backup center Jon Koncak signed a new contract for $13.5 million over six years. And Koncak is an even bigger but that the G-Man.

But Gminski has no regrets about not waiting a few more months to sign, even though the Koncak bombshell would have upped the ante. “Nobody here has a crystal ball,” he says. And as a prominent sports agent who represents more than one NBA center says, “He might have gotten more, but so what? Unless it’s an ego thing, what’s the after-tax difference between $9 million over five years and $11 million over five years?”

****

Besides, on the whole, Mike Gminski would rather be in Philadelphia. In July, he and his wife, Stacy Anderson, bought a large, new house in Villanova, just down the road from Julius Erving. They’ve just moved in, as is indicated by the absence of furnishings and abundance of boxes (“They multiply at night,” says Stacy). Even so, it’s quite a spread. The room count is well into double figures, the master bathroom possesses the biggest stall shower in Montgomery County, and there’s a mirrored workout room downstairs—complete with exercise equipment and built-in sauna. At this point, the tennis court in the backyard is still in the daydream stage.

Right now, Mike is in the kitchen (the granite countertop has just been put down) munching on a tuna hoagie (he’s off red meat) washed down with some Orangina. Stacy’s in her office, off to the side on the ground floor. Up until the move, she’d been a vice president of marketing at Smith Barney in New York (the youngest VP in the history of the firm, her husband points out).

After Mike was traded from New Jersey to the Sixers in the middle of the 1987-88 season, they embarked on a commuter marriage from hell, splitting their time between a North Jersey house and a City Avenue apartment—with Mike taking off for various NBA cities and Stacy logging more time on the Metroliner than most conductors. A year-and-a-half of that lifestyle convinced them the emotional and physical costs were too high, so Stacy—who isn’t particularly tall, has big black-rimmed glasses, wears her dark hair in a dramatic pompadour, and is vivacious where her husband is laid-back—resigned from her job to start her own business, doing marketing and promotional work for banks and brokerage houses.

Options, careers, a rejection of the concept of the maiden name: all of this may give you the idea that Gminski and Anderson are . . . well, the word is too much of a cliché to even put in print. Let’s go with the standard euphemism: “the y-word.” [Yuppies]

The point is, Gminski and Anderson are not the typical NBA couple. “When Mike first started in the league,” Stacy once said, “I was the only wife who had a job, much less a career.” They’ve put off having children for the sake of both their careers. Mike’s favorite band is Little Feat. Since their last birthdays, they both even qualify for “thirtysomething.”

But Gminski doesn’t fit all the stereotypes. For one thing, he drives, not a BMW, but a smoke-spewing Audi with Jersey plates, a Duke sticker, and 98,402 miles on the odometer. (He says he’ll trade it in when it hits 100K.) “A car is the most ridiculous expenditure one can make in a lifetime,” he says. “I had the choice between buying two Mercedeses or putting a down payment on the farm.” (That’s the country place in the Catskills to which he and Anderson like to repair for vacations and long weekends.) For another, his best friend with the 76ers isn’t some Ivy League marketing executive, but his frontcourt partner, down-to-earth Charles Barkley.

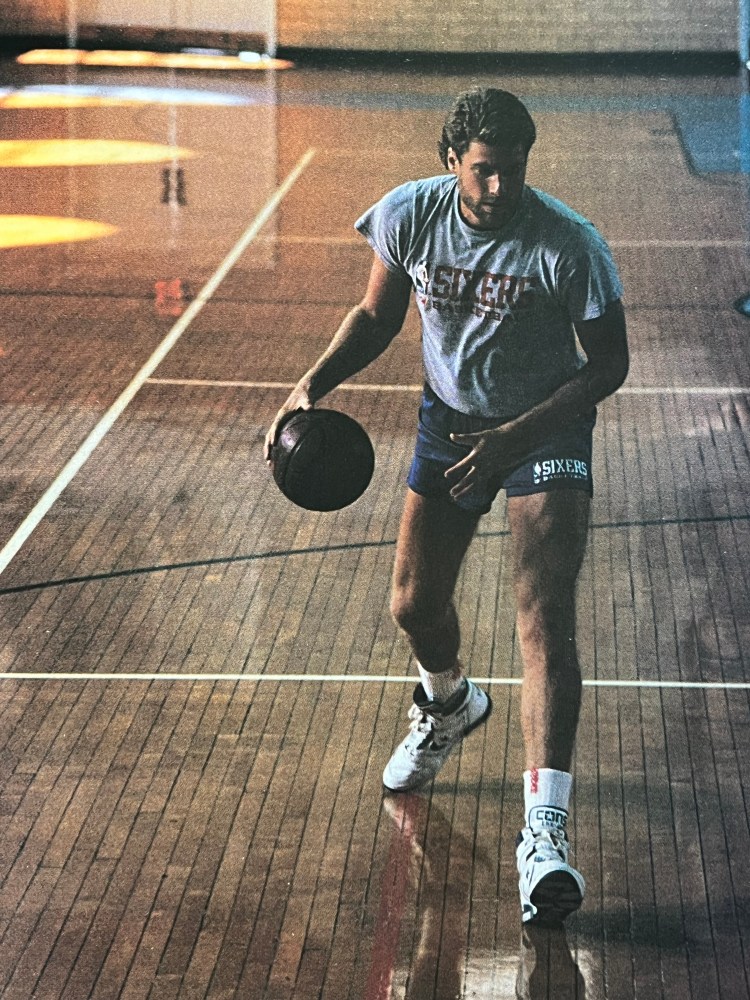

And though his wife found her niche in the white-collar world of Wall Street, Gminski, the scion of several generations of carpenters that go back to Poland (his mother’s family is from Denmark), has a blue-collar approach to the game of basketball. This is made patently clear after lunch, when he gets in the Audi for the five-minute drive to the Villanova University weight room. There he embarks on 90 minutes of weight training, all Olympic-style lifts “to develop explosiveness in the lower back, thighs, hips. That’s where the game is played.”

It’s a daily routine throughout the summer. In the morning, he swims—easier on the knees than running. He doesn’t play a single game of basketball between the last playoff game and the start of training camp (only some shooting to keep his limbs loose and his shot from getting rusty)—just the lifting and swimming, all by himself, day after day.

“I always thought it was ironic,” says Stacy, a swimmer in college, “that I did an individual sport and always needed a coach to drive me along, where Mike plays a team sport and is completely self-motivated.” And so it goes at ‘Nova. As he methodically grunts and jerks and cleans, a couple of hulking linemen look on in a kind of awe.

****

Everyone who knows him says that Gminski has always been a nut about practice and conditioning. “When he was a kid, he used to love Ted Williams’ book on hitting,” Joe Gminski says. “On the second-to-last page it says, ‘To succeed you need three things.’ Then you turn the page, and it says, ‘Practice, practice, practice.’ Mike used to take that book into the pot with him every day.”

The senior Gminski (who, at 6-8, played basketball at the University of Connecticut) attests that he spotted Mike’s athletic potential at an early age. “Mike was two or two-and-a-half,” he says. “I remember that it was winter, and he was wearing his snowsuit. We’d play a game where I tossed him the football and then he’d run at me. I’d tackle him, and each time I hit him a little harder. Finally, I belted him to the ground. Tears welled up in his eyes, but he didn’t cry. He could have said, ‘I don’t want to play anymore,’ or he could have gotten up and kept at it. He got up, and this time I threw him the ball, and he ran at me. I fell down, as if he had knocked me over. He got up laughing. That’s when I knew he was an athlete.”

Mike continued with football and actually won the Punt, Pass, and Kick championship at the age of 11, but his first love was baseball. Unfortunately, by the time he was a sophomore at Masuk High School in Monroe, Connecticut, he was 6-9 and pitchers could get him out by throwing at his knees. This coincided with the clearing up of a childhood asthma problem, so the time was right for a complete switch to basketball.

“My father felt that nobody had worked with him to develop his skills, and he wasn’t going to let that happen to me,” Gminski says. So Joe Gminski quit his job, moved his family in with his mother, built a court, and spent all his time teaching his son to play basketball. There were weight programs, drills, a special diet—just like today. To pay the bills, Mike says, his mother worked “in sales.”

It was a difficult situation. Mike was an only child, and he says there may have been too much pressure, too much time spent together. His relationship with his father today, he says, is “tenuous.” (Stacy is an only child, too. “It makes for an interesting marriage,” she says. “’Share? What’s share?’”)

But the system worked. “The most important thing my father did was give me a love of practice,” Gminski says. “I wasn’t born with a lot of natural ability. He showed me what hard work can do.”

He played JV ball as a freshman and averaged three points a game. He was, says Masuk athletic director John Giampaolo, “a klutz.” His sophomore year, he was first-team All-State. By that time, Gminski’s combination of size and skill was unstoppable; his junior year, he broke Calvin Murphy’s state high school scoring record of 40.1 points a game.

He felt he had gotten all he could out of high school. As he says, “What was I going to do, score 50 points a game?” So he decided to graduate a year early. This wasn’t a problem academically: he was second in his class, and his SAT scores were an impressive 1,200. He only took the test once, Gminski is quick to point out (the implication being that he could have done even better a second time). It wouldn’t be a social problem either; Gminski had always had the only child’s ease with adults. His usual lunch partner at Masuk was Giampaolo. He enrolled at the only college he visited, Duke.

****

Gminski’s college career was four years of glory, marred only by the Blue Devils’ failure to win an NCAA title. The 1977-78 squad featured Gene Banks, Kenny Dinnard, and Jim Spanarkel, along with the G-Man, but they were defeated in a memorable final by Kentucky. Asked to assess his Duke years, Gminski falls back on that old reliable, the but: “I was never real flashy—my career scoring high in college was 33 points. But I wound up as Duke’s all-time scoring, rebounding, and shot-block leader.”

He also wound up with a 3.6 grade point average, an abiding loyalty to the school, a dressing style (haute preppy) that he’s only now trying to transcend and a wife. Stacy Anderson was a swimmer from Pittsburgh; she and Mike met when they were freshmen. By the last semester of their senior year, they got around to dating. It wasn’t the last time Gminski would be accused of being slow.

The Nets drafted Gminski with the seventh pick in the first round. He and North Carolina’s Mike O’Koren, drafted right before him, were supposed to turn around the franchise, still mired in the post-Dr. J doldrums. They didn’t.

Though the cliché hadn’t been coined yet, Gminski was a “role player” with the Nets, capable of great contributions if surrounded by talent. What’s more, Gminski, just 20 years old when he graduated, felt for the first time that his youth was a problem. “I was 17 as a freshman in college, but the oldest guys I was going up against were 20 or 21,” he says. “Now I was playing against 30-year-olds—that’s a big difference. Also, I was a late bloomer physically. If I could change anything about my basketball career, I’d take a fellowship, like Bill Bradley and Tom McMillen, did, and go into the NBA a couple of years later.”

Matters weren’t helped when he injured his funny bone in training camp, leaving his shooting hand numb for the 50 games he played before having an operation. Even worse, he suffered a staph infection in his back that summer. It was initially misdiagnosed as back spasms, and Gminski lay near death with a 106-degree fever before his doctors realized the problem. He recovered soon enough to play a good part of 1981-82 season, but he wasn’t any more impressive, and he was pigeonholed as a backup.

In a way, it was the best thing that could have happened to him. Being a second-stringer gave Gminski a chance to learn his trade in practice against wily veteran Maurice Lucas and, later, Darryl Dawkins. It took some of the pressure off, too, and it gave his body a chance to catch up with the rest of the league. He came to some realizations about what he could and couldn’t do: “If I was going to survive, it would be because I was steady, and because I had to think a little more.”

Nor did Gminski ever grow despondent over the fact that for the first time ever he was something less—muchless—than a local hero. “He used the bad times as a motivator,” says his wife. “He wanted to prove that he could play in the NBA—not so much to a bunch of strangers as to himself.”

By his fifth season, when opportunity struck, he was ready. Dawkins inspired as many whistles with the Nets as he had with the Sixers; the more foul trouble he got into, the more Gminski got to play. To prevent Double D from fouling out, the team eventually started Gminski, with Dawkins coming off the bench. In 1985-86, when Dawkins suffered a series of injuries, the G-Man averaged 31 minutes.

His other numbers were Impressive that year, too: 16.5 points a game, 8.2 rebounds, 89.3 free-throw percentage. A major contributor of his success was the hiring of Stan Albeck, the latest in New Jersey’s string of coaches. Albeck had remembered that in college Gminski had very effectively used a jump hook from the low post. The coach encouraged G-Man to resurrect the shot, which gave him an inside option to go along with his always dependable outside game. Albeck, wanting the team to improve its free-throw shooting, instructed the players in an elaborate finger-placing ritual. Within a few weeks, all the players had dropped it—except Gminski, who still uses it and has been among the NBA free-throw leaders ever since.

Not the least of Albeck’s contributions lay in the area of grooming. One time the Nets had a winning streak that would reach 11 games, and Gminski pledged not to shave until the team lost. Albeck urged him not to shave even then. “I’ve noticed that most white backup centers just don’t get calls,” Albeck says, “so I told Mike that a beard would make him look more macho, less like a choir boy. I said, ‘I want you to look like a goddamn woodsman.’”

With the beard, the mature Gminski game was in place. On offense, it consisted of the reliable 15-18-foot jump shot, taken whenever it was conceded, and the surprising jump hook from the baseline. (The hook gives Gminski, who reckons his vertical leap at “about the size of a Sunday paper,” his only chance to shoot overmost defenders.) The upshot was 17 points a game—typically, a couple of tip-ins and seven or eight free throws, including a technical. (It does wonders for your scoring average when you’re a great foul shooter.)

And on defense, helped by the down-and-dirty moves Maurice Lucas taught him—“when you can hold, when you can move your legs, how to move a guy out of position”—he had become a kind of man-to-man arbitrageur, skilled at taking the last margin of leeway the refs would allow.

This was the game that the Sixers were after when they acquired Gminski, together with Ben Coleman, for Roy Hinson and Tim McCormick in January 1988. And so the team’s travails at center, which began with the trading of Moses Malone and continued with the collapse of Jeff Ruland and the disposal of the draft pick that could have gotten Brad Daugherty, were over. John Nash and Jimmy Lynam profess their complete satisfaction with their center—especially after he, on the team’s suggestion, went from 272 to 255 pounds and from 19 to 13 percent body fat last summer.

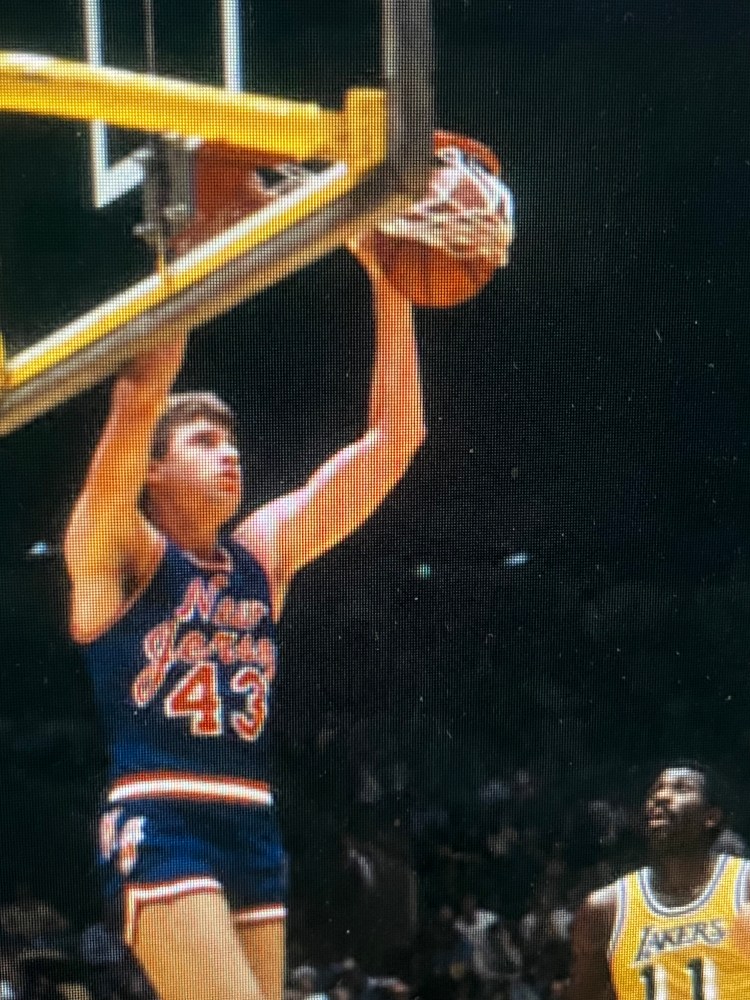

What sealed his acceptance was his performance in last year’s playoffs against the Knicks, in which he held Patrick Ewing to well below, his season average by forcing Ewing to set up a couple of feet farther out than he would have liked. “Those two feet are the difference between him scoring 40 percent and 60 percent of the time,” Gminski says.

No, the Sixers brass feel the Gminski deal has worked out even better than expected. His outside game has turned out to nicely complement Barkley’s interior pneumatic drilling. And—especially with Mo Cheeks gone—he provides a young team with a salutary veteran presence. “There’s so much to be said for Mike in terms of intangibles,” Nash says. “He’s a calming effect on Charles, who tends to erupt. There’s a maturity about him that rubs off well on teammates. He’s a consummate professional.”

And to those who still consider Gminski at best a consolation, prize compared to what might have been, consider this: Gminski averaged almost as many points as Daugherty last year (17.2 to 18.9), more rebounds (9.4 to 9.2), and more than twice as many blocked shots (1.3 to .5)

No if, ands, or buts.

****

His weight session over, Gminski—tanned and bleached blonder than usual after a week’s vacation in Florida—walks over to the Villanova gym. The summer stragglers shooting hoops look appropriately impressed with this NBA giant in their midst. He starts his shootaround with a couple of dozen layups from either side, then starts systematically working his way around the perimeter. Every so often, he’ll go over to the foul line, where he once made 44 straight as a pro. What’s his personal record for consecutive free throws? “I don’t know,” he says, “because I never take more than a few at a time. It doesn’t make any sense to shoot hundreds in a row because you don’t shoot hundreds in a row in a game.”

He’s working on a few specific things for the season. The first is a pump move, so he can give the matador treatment to leaping shot blockers. He’s also experimenting with a fall-away shot a la Moses Malone, a low-box alternative to the jump hook. Then there’s the three-pointer, never before in his repertoire (he took and missed six last year). He’s come up with a kind of one-handed set-shot style, and after a few miscues, he starts popping them.

“Jimmy Lynam was watching me shoot them the other day,” Gminski says. “I don’t have the green light yet, but I am definitely making some inroads.” [Ed. Note: During the 1989-90 season, Gminski would make three of 17 (17 percent) and two for (14 percent) during the following year. So, the inroads would remain just that.]

****

Mike Gminski will no doubt develop a decent three-point shot, because, as everyone agrees, when Mike Gminski sets his mind to doing something, he does it. As his college coach, Bill Foster, says, “Mike’s as good as any I’ve ever seen at knowing what he has to do and going out and doing it.”

It’s the way he approaches things. A couple of years ago, when Mike was thinking about going into politics after his NBA career, Stacy found a reading list—autobiographies of great statesmen—that Elizabeth Dole had compiled for [husband] Robert. Gminski plowed through the books, one by one.

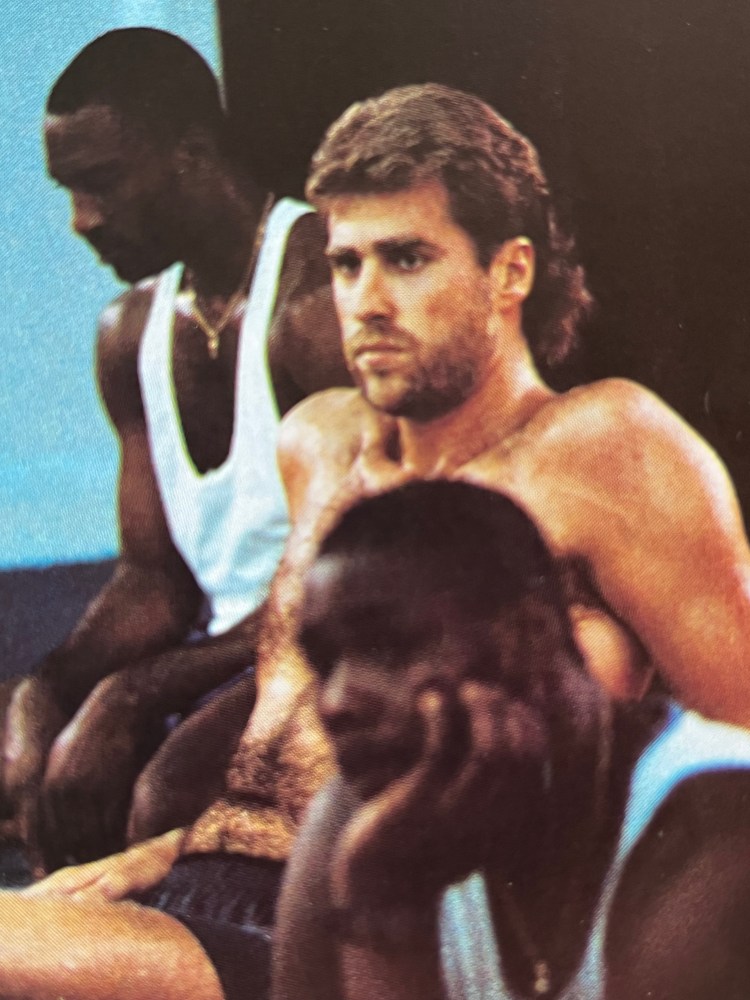

Of course, anyone who’s spent any time watching him knows that this determination, more than his deficient shot-blocking or his inability to make a spinning move to the basket, is his weak point in a league that worships entertainment. Gminski is not without grace on the court, yet rarely has there been a first-quality basketball player—he’s just below the all-star level, the consensus is—who displays such a complete and palpable lack of freedom and joy.

As a kid, he says, his sports idol was Bjorn Borg—as much for his expressionless demeanor as for the way he dominated his sport. Following Bjorg’s example, Gminski today makes a conscious effort not to show emotion during games. “I don’t want people to be able to read me,” he says, “to know when I’m tired, intimidated, angry.” He’s never been thrown out of the game, and he can count the technical fouls he’s received on one hand. The most displeasure he’ll usually permit himself is a grimace and a quick handclap.

Gminski almost never makes a bad pass or a goofy shot. How could he? Inherent, implied, in every move he makes are thousands and thousands of hours of solitary practice, in gyms like this one, or in his backyard in Monroe . . . say on an early November afternoon, the light getting dim, his father passing the ball out to him for shot after shot after shot. He tries so hard. You can sense it most of all on defense, when he concentrates so intently on his man that he often lets guards drive right to the basket without so much as a glance.

But it even shows up in Gminski’s most vaunted quality, his consistency. Here’s a man whose scoring average has been no lower than 16.5 and no higher than 17.2 points per game over the last four years. It’s almost scary. It seems that in some subconscious and transcendental way, Gminski has seen to it that his numbers are as unvarying as his demeanor.

The paradox is that off the court, Gminski is funny, friendly, relaxed, by all evidence, and all accounts, a prince of a fellow. “He’s off-the-board in terms of who he is as a guy,” says Jimmy Lynam. But on the court, the mask never comes off.

Except for once in a great while. The one time that Gminski memorably showed excitement last year was in a game against the Knicks, when he was under the Sixer basket and Charles hit him with a half-court, pinpoint, behind-the-back pass for a layup. Knicks coach Rick Pitino immediately called timeout, and Gminski ran to the bench grinning and clapping.

“It was the only NBA highlight film I ever made,” Mike Gminski says, not at all wistfully.