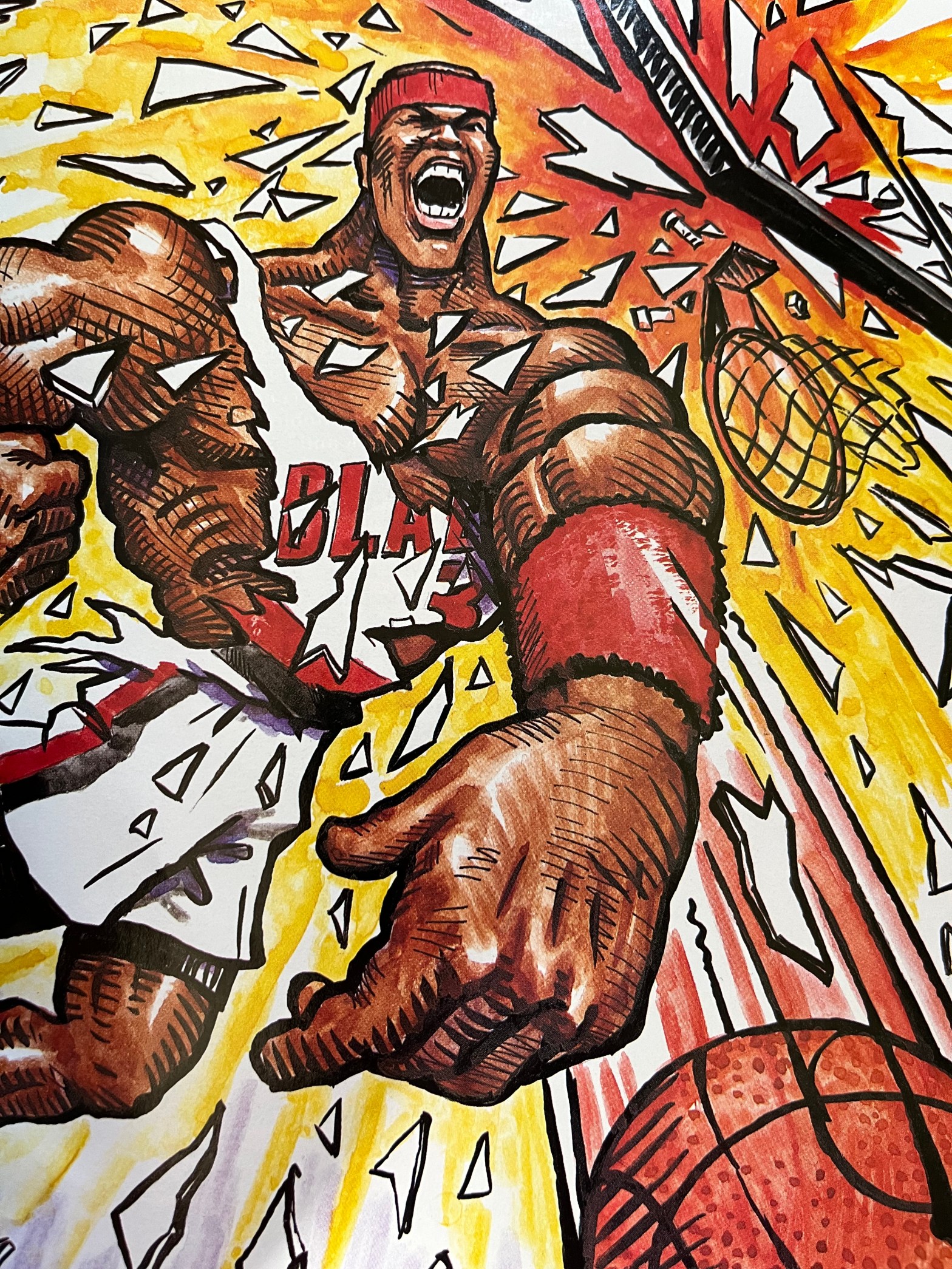

[Super Swingman . . . and Uncle Cliffy. That was Robinson’s nickname for the signature dance that he broke out a few years earlier at a Portland night club. Uncle Cliffy also captured the yin and yang of his reputation as a flighty kid and trusted veteran talent.

But Robinson is interesting to revisit in our position-less present for being a seminal jack-of-all-frontcourt-positions 30 years ago. He stands out as one of the first modern super swingmen and played a big part in opening up the floor for tall, quick guys to show just how much game they really had outside the paint. For all of his then-freakish versatility, Robinson was named the NBA’s Sixth Man of the Year in 1993. Strangely, this article, from the April 1994 issue of the magazine Rip City, doesn’t mention Robinson’s honor. But writer Terry Frei, always solid, hits all the other major points. If you like this article, Frei has since become a prolific author. If you’re looking for something good to read, take a look at some of his titles.]

****

Since the Portland Trail Blazers drafted him in 1989, Clifford Robinson has defied categorization and played an often-spirited game of one-on-one against his reputation. An unquestionably talented, skinny forward from the University of Connecticut, Robinson rarely tried to camouflage his emotions. His college coach, Jim Calhoun, now scoffs at the notion that Robinson had a “down” senior season and says he spent the predraft period telling skeptical NBA personnel that they were overreacting to Robinson’s volatility and his trademark glare.

Still, some scouts were wondering: Was Robinson going to be another of those skilled headcases who never fit in? And it wasn’t just an issue of attitude. The 6-10, 215-pound Robinson seemed too lean to be a center or a power forward, and not quite smooth enough to fit the small forward prototype.

Five years later, even some of Robinson’s occasional critics—and this is coming from the laptop computer of one of them—admit this: Instead of letting it run him out of the league, a determined Robinson has taken advantage of not being a “natural” anything. He has put on 20 pounds and established himself as one of the top forwards/centers in the NBA, a legitimate all-star.

The slash is crucial, since Robinson has little company—Danny Manning, Sam Perkins, Shawn Kemp—in the fraternity of men who can swing effectively across the front line. And even when he has been introduced as the starting center, as he has for much of this season, a qualification is necessary.

When Robinson seems to be the Blazers’ center in a front line with Buck Williams and Jerome Kersey, for example, Williams often ends up matched up at both ends of the floor with the other team’s center, in part because Robinson inevitably gets into foul trouble against the league’s centers. “I am the center, but I’m not the center,” says Robinson, making perfect sense. “Buck and I switch off on different players. It all depends on who has the most fouls.”

But Robinson can step into the true center’s role, if necessary, and his versatility remains a crucial component in Portland’s game. Even if he is plugged into the power positions (center and power forward), Robinson can take advantage of his extraordinary quickness for his height. He can attack the boards at both ends of the court, run the floor, and leave the bigger opponents in his wake.

At small forward, he has to give his man more room than perhaps does a Jerome Kersey, but Robinson often can make up for that with his reach. “His best position might be small forward, where he has a huge advantage over some guys in size,” says coach Rick Adelman.

Robinson agrees, but understands why the Blazers can’t afford to lock him into a forward’s role. “I have the ability to guard smaller players because of my quickness,” Robinson says. “But on offense, I can go into the paint and take advantage of them with my size. For this team, me switching and playing three different positions is the best for the team because it gives everybody opportunities.”

****

Five years into his career, this seems just as striking as his versatility: Robinson has thrived in situations which provided him opportunities to live up—or down—to is collegiate image. Would he rebel if he continued to come off the bench? Wouldn’t his game suffer? And could his restlessness become a problem?

The answers, to varying degrees, were no.

The man who came into the league with the reputation for immaturity occasionally has allowed it to rise to the surface. His emotionalism, for example, has put him in the middle of the Blazers, frequent preoccupation with the vagaries of officiating. But for the most part, he’s used that negative reputation as motivation, channeling his energies into proving it unwarranted. The reality is that without that image, he wouldn’t have lasted until the Trail Blazers could draft him.

As the 36th selection, Robinson went in the same neighborhood of the draft that landed Portland such never-finished “project” picks as Panagiotis Fasoulas, Lester Fontville, and George Montgomery. The Blazers also have not had a great record with other talented men with attitude question marks following them out of college (Walter Berry, Ronnie Murphy). The Blazers took Robinson—after they selected Byron Irvin in the first round—at the stage of the draft when he was taking a chance on.

To their credit, the Blazer trumpeted Robinson as an exceptional talent for a No. 2 pick. They have said that before and since about ultimately forgettable No. 2 choices, but it’s not automatic. They also have at times admitted that a No. 2 pick is a long-odds player whose best qualities are that he does not kick his dog, he is nice to his mother, and he has to duck through doorways. With Robinson, the Trail Blazers hoped he could do more than make their roster and be the final man on the bench for a season or two. But they had no idea Robinson could become this valuable.

“I can’t lie like that,” says a laughing Brad Greenberg, the Blazers’ vice president of player personnel who helped scout Robinson. “He was much thinner back then. Because he was the tallest guy on campus and was playing center, a lot of people were looking at his inside game. They did not like the way he competed there, because he was taking a lot of jumpers. I saw him more as a combination-type forward and was especially intrigued by his potential to be a small forward.”

****

Calhoun, who has been Connecticut’s coach since Robinson’s sophomore season, now relishes being able to say to any and all NBA scouts about Robertson: “Why didn’t you listen to me?”

He and Robinson had their moments of disagreement, but Calhoun maintains that they weren’t monumental and that Robinson’s attitude was praiseworthy. Calhoun also leaves the impression that he’s secure enough to allow his young players their occasional outbursts of honest emotion and opinion—as long as they work hard.

Calhoun says he always will be grateful for the way Robinson persevered to regain his academic eligibility after running afoul of a since-changed formula that left him on the sidelines, despite a decent 2.3 grade point average.

“Even the president of the university told him he got a raw deal,” says Calhoun. “Other schools contacted him, by the way, whether they should have or not. He worked and got back into school, and I’ve always appreciated the way he showed us loyalty. Now, look, I’m not saying Cliff was perfect. But we’re dealing with young kids at 19, 20, trying to establish their own identity.”

Calhoun says Robinson’s college play foreshadowed his professional versatility—and that it should have been obvious. “When I took over the program, Cliff didn’t have an established game,” says Calhoun. “Sometimes guys bring great things right to your program, sometimes they bring excess baggage. Cliff didn’t bring either, and we were able to mold him, I guess you could say.

“He was a very versatile player in college, and you could see that he was going to get bigger and stronger. What he brought was a great work ethic, a great body, and athletic skills.”

After he joined the Trail Blazers, Robinson’s versatility earned him more minutes early in his career and accelerated his development. Lest we get carried away, some flaws remain. Once capricious, Robinson’s jump shot has become fairly reliable, but he sometimes seems convinced he’s another Eddie Johnson, a streak shooter extraordinaire. He’s not. He still gets out of control, but those moments are increasingly rare and are acceptable tradeoffs in the big picture of Robinsons emotion-driven game.

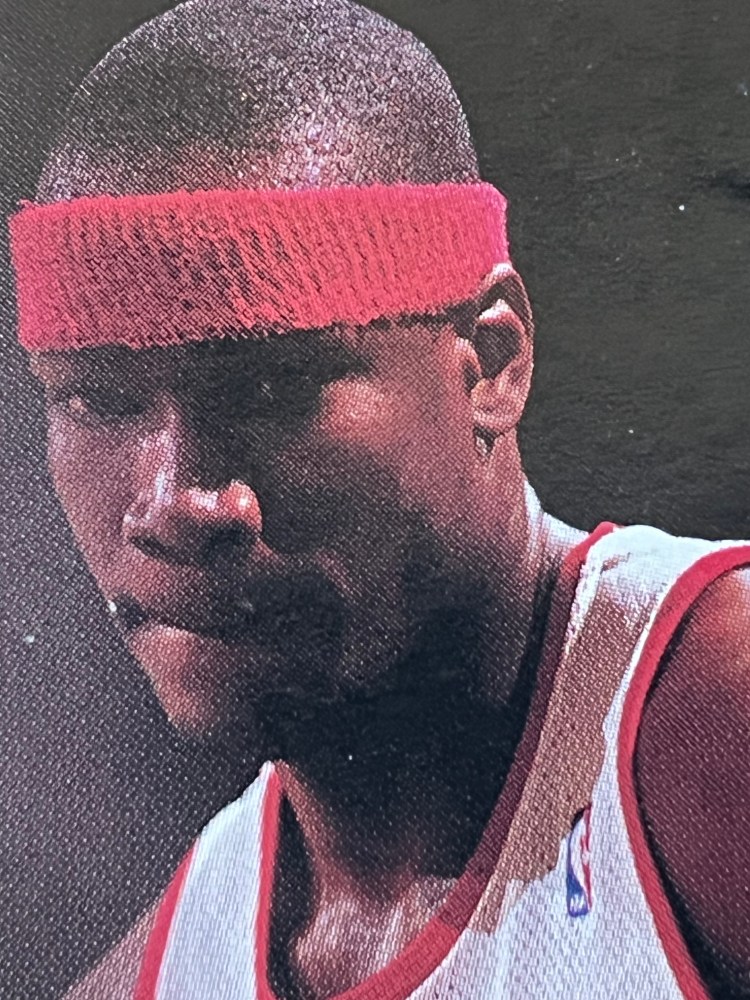

The bottom line for the Blazers: Robinson is about as effective as possible at the wildly desperate tasks required of a front-line player in the NBA of the 1990s. And that’s why Adelman was so reluctant to start him. Adelman preferred to use Robinson as his “X” factor in early game adjustments. Eventually, Robinson would be getting ready to wrap his headband around his shaved skull. And when waved in, he would take the place of Chris Dudley or Mark Bryant or Buck Williams or Jerome Kersey or Harvey Grant.

Even if Robinson becomes a “permanent” starter—and that seems inevitable—his adaptability will continue to magnify his importance. “I admit what I like about starting him,” says Coach Adelman, “is that it’s easier to get him 36 minutes or so.”