[Long article, no need here to introduce Utah’s John Stockton and Karl Malone. Their Hall-of-Fame reputations precede them. However, I must introduce Lee Benson, the great sports editor of the Deseret News and the silver pen behind this article. It appeared in the 1989 Street & Smith’s Pro Basketball annual. Enjoy!]

****

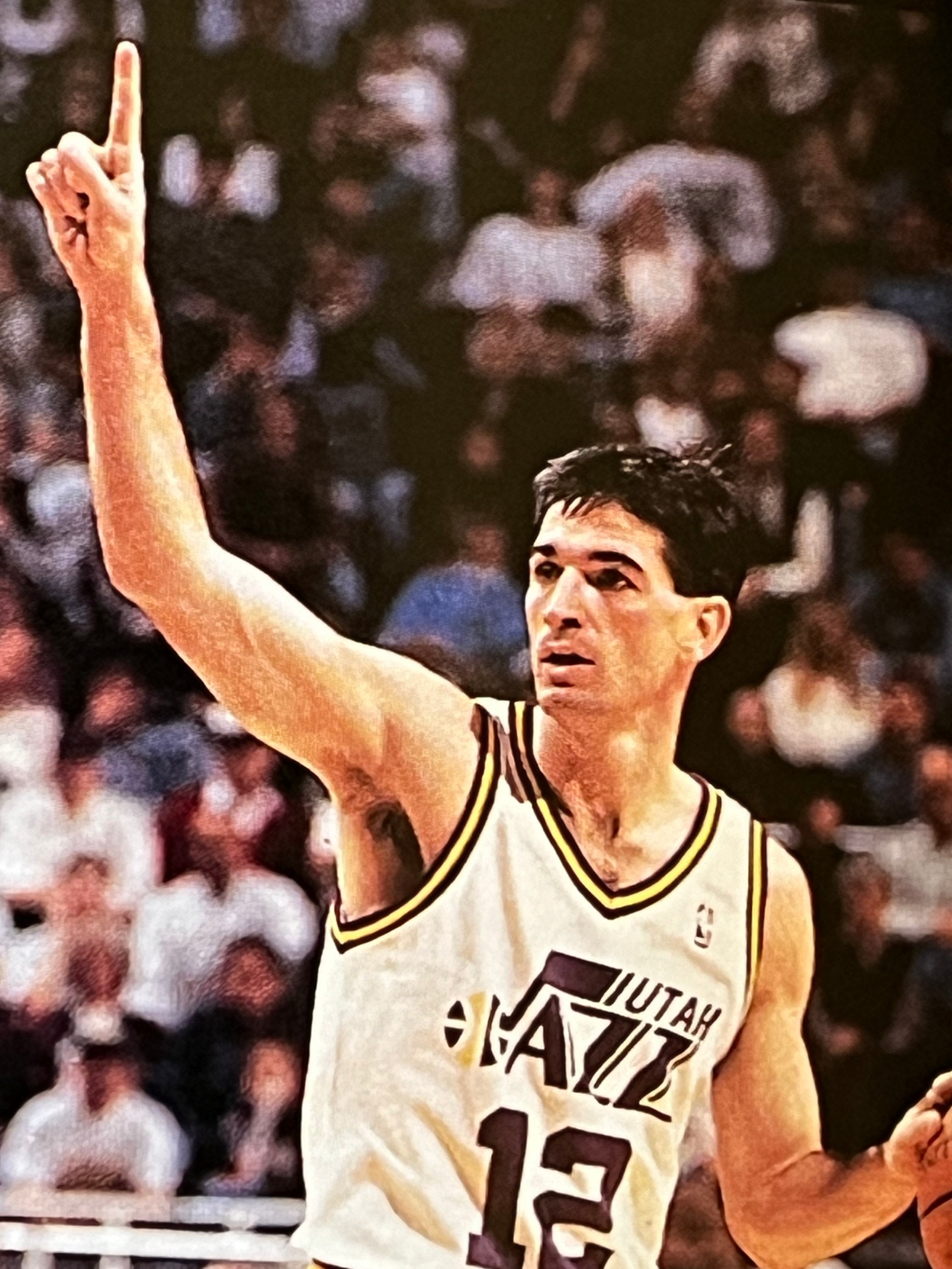

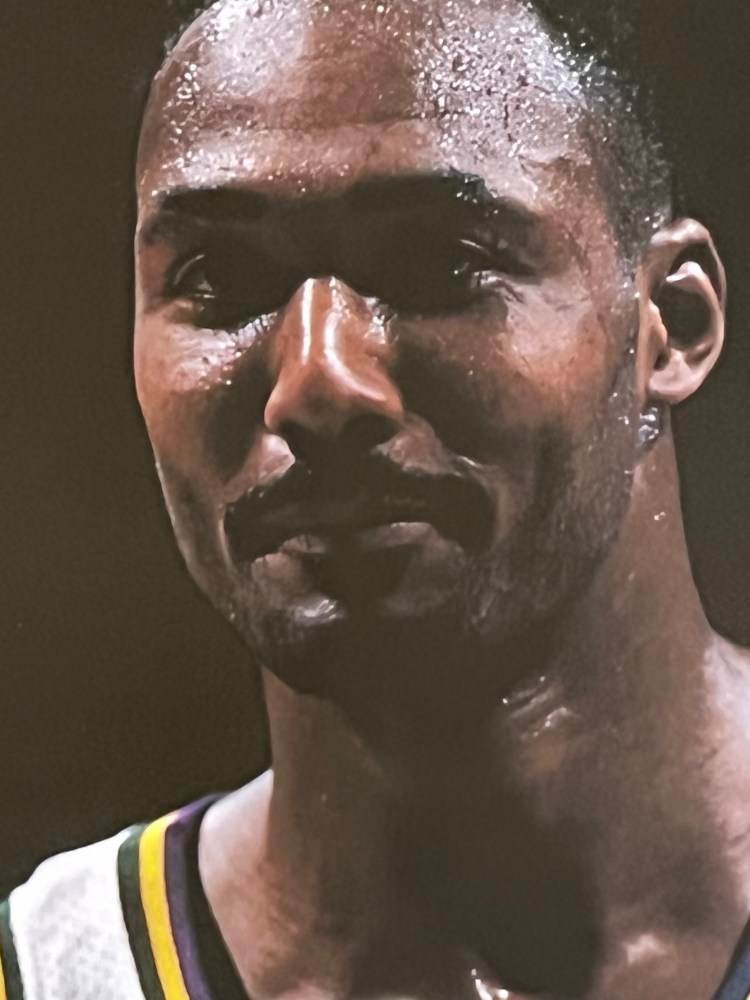

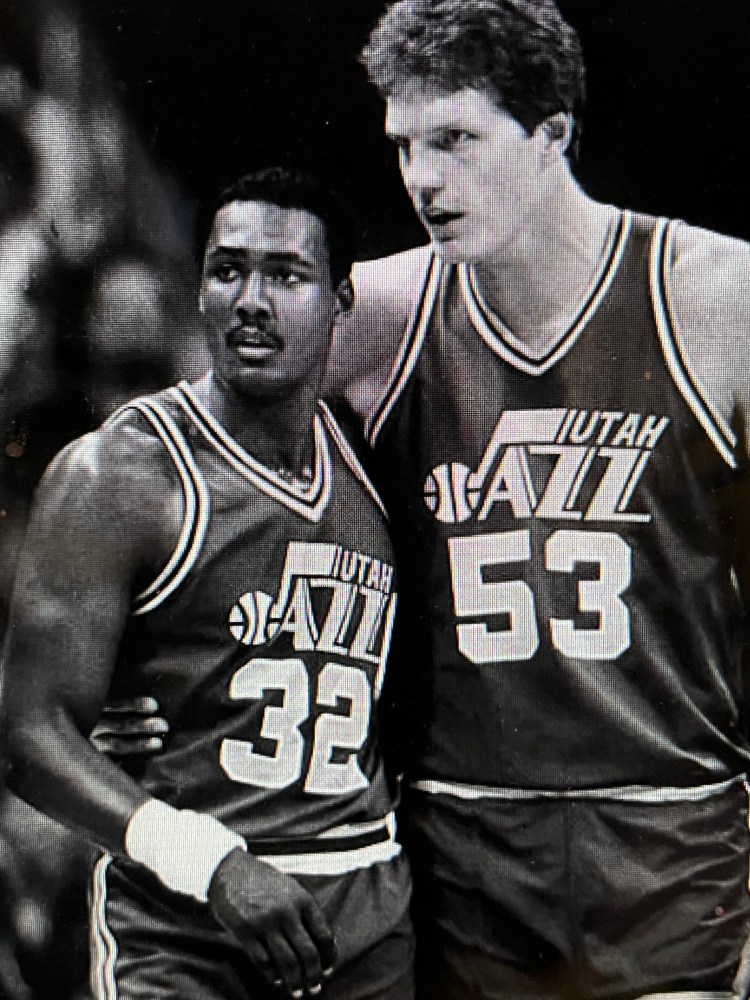

On the one hand, there’s a 6-foot-1 introverted white guy from the Pacific Northwest who played his college ball at an obscure college in his hometown and who goes by the name John. On the other hand, there’s a 6-foot-9 extroverted Black guy from the Deep South who played his college ball at an obscure college near his hometown and who goes by the nickname, The Mailman.

That the two of them would come together in Utah and turn themselves into the NBA’s hottest one-two punch since the invention of the 24-second clock is as unlikely as cold fusion in a University of Utah chemistry lab.

But put John Stockton and Karl Malone together, and you get some HEAT; enough to light up a city the size of, oh, say, Salt Lake, and enough to light up a basketball game the size of, oh, say, the 1989 All-Star Game.

In that showcase game last February, played in the Houston Astrodome by every healthy star in the NBA, what it came down to at the end was this: Either Stockton or Malone was the best player on the floor.

In this case, Malone, who had 28 points and nine rebounds in the West’s 143-134 win, was the top choice, followed closely in the official MVP balloting by Stockton, who had 17 assists and 11 points. But the choice hadn’t been an easy one for the panel of media voters, just as it hadn’t been easy for Stockton and Malone’s Utah Jazz teammates when they voted for their team MVP the season before (the Jazz players exhibited survival instincts in that vote and went for the guy who really makes the deliveries, choosing Stockton over Malone—but only barely).

John Stockton and Karl Malone represent the basketball version of the chicken-and-egg question. Realizing that you can’t have one without the other, which is more important the jab or the left hook? What do you like, a sunrise or a sunset? Is it better to give or to receive? But, then, the Jazz spend a little time these days worrying about who’s on top. Indeed, in 1989 the team dispensed with voting for its own MVP. Why make anyone mad (as Malone had been the year before when the voting results were announced)?

Instead, the Jazz management allowed the Salt Lake community to decide between Malone and Stockton. It was a lot like asking Utah skiers to pick a favorite local world-class resort between, say, Alta and Snowbird. The vote was so close it was declared a draw.

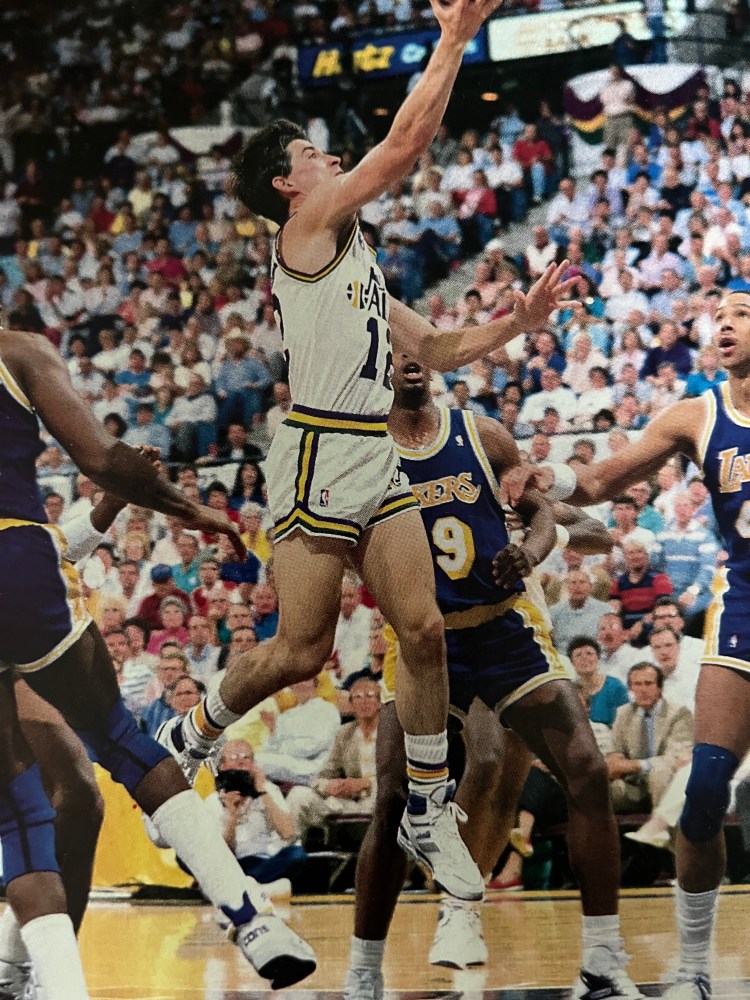

Mainly, what the Jazz are doing is riding the Stockton-Malone ticket as far as it will carry them. In 1987-88, when these two got cranking, the Jazz were good for a franchise-high 47 wins. In 1988-89, they were good for yet another franchise-high 51 wins.

In the process, Stockton has emerged as one of the league’s premier point guards and Malone as one of the league’s premier power forwards. Statistically speaking, Stockton has only Magic Johnson as a peer at the point, while among power forwards, only Charles Barkley comes close to matching Malone.

Together, they’re a regular Michael Jordan. Figure this: As a tandem during the 1988-89 season, they scored an average per game of 46.2 (Malone 29.1, Stockton 17.1), 13.7 rebounds (Malone 10.7, Stockton 3.0), 20.3 assists (Malone 2.7, Stockton 13.6), and 5.01 steals (Malone 1.8, Stockton 3.21). Malone was second in the league in scoring, fifth in rebounding, and third and MVP points with 362. Stockton was first in the league in both assists and steals, 10th in field goal percentage and seventh in MVP points with 28.

No other guard-forward pairing in the NBA could match the above. Only Magic Johnson-James Worthy of the Lakers, Kevin Johnson-Tom Chambers of the Suns, Fat Lever-Alex English of the Nuggets, and Jordan-Jordan came even close by comparison.

It’s no wonder that Jazz coach Jerry Sloan, when asked if he’d trade Stockton-Malone for any other point guard-power forward combination in the NBA says, without hesitation, “No,” and looks at you like you’re crazy to even ask. And it’s also no wonder that last season the Jazz called the two of them into their renegotiation office and wrapped them in Mardi Gras-inspired uniform colors into at least the next century. Stockton on an 8-year, $10 million deal, and Malone on a 10-year, $18 million deal. As Jazz owner Larry Miller, who approved the long-term contracts, explained, “If those two guys aren’t around here, I don’t want to be either.”

****

So, how do you tell them apart?

Well, John Stockton is the shorter of the two, and he’s the one who, if you were sitting at a dinner table and wanted, say, the sour cream and chives for your baked potato, he’d have them to you before you could say, “Please pass . . .” He came to pass. In the history of NBA basketball, nobody has been as giving as Stockton has the past two seasons.

He broke Isiah Thomas’ NBA season assist record of 1,123 by delivering 1,128 assists in 1987-88, and then to show it was no fluke, he handed out 1,118 last year, giving him the No. 1 and No. 3 playmaking spots all-time. To add validity to his totals, almost exactly half of his more than 2,000 assists the past two seasons have come on the road.

At 6-foot-1 and 175 pounds, Stockton is not intimidating physically—certainly not in the NBA. And being white, he is hardly looked on as a speed merchant. But if five years is enough to pass judgment, there may not be a more physically fit player in the league, or a quicker guard. Stockton is yet to miss a Jazz game, regular season or otherwise. He has played in 410 straight regular-season games, ranking first among current players in that ironman category, and in 1988-89 he was on the floor 39 minutes a game. According to Frank Layden, his former coach, “He never gets tired. Never.”

And his quickness? It’s, well, deceptive. “Time and again, I’ll hear other players comment about Stock,” says Sloan, “they’ll say he doesn’t look like he’s going very fast, and then, all of a sudden, he’s past them.”

It can be a rude awakening, just as it was several years ago for an aspiring college point guard from Los Angeles who was trying to find a school to play for. The guard was granted a tryout—NCAA investigators should look the other way—by Gonzaga University in Spokane, where Stockton was the point guard. The coach asked the kid from L.A. to play a little one-on-one against Stockton. He did, and in the course of the next 10 minutes, began to rethink if he could ever play on the college level. Stockton beat him to every ball and every basket, and the guard went back to L.A. without an offer.

Only much later, when he was on his way to an All-American senior season at the University of Arizona in 1988—and Stockton was making a lot of other people, in the NBA yet, look slow—did Steve Kerr (who’s now with the Phoenix Suns), appreciate who he’d gone up against in Spokane.

It’s that deceptive quickness that not only makes Stockton the top stealer in the league—his 3.21 steals average led the NBA the past season, and his 2.95 average in 1987-88 was third—but also triggers his whole unique game, which, according to less an authority than Isiah Thomas, “is a joy to watch and awful to play against.”

As Sloan explains, it’s Stockton’s ability to get the ball on the defensive end, either off a steal or an outlet pass, and then use his quickness and his decision-making on the offensive end that makes him a complete point guard. “He creates opportunities other people just don’t create,” says Sloan. “He is such a good decision-maker. You want the ball in his hands as much as possible.”

Stockton’s decisions account for approximately half of all the Jazz’s points. His 13.6 assists per game, taking into consideration three-point shots, account for a little over 30 points a game, and he adds his 17.1 scoring average to that. His own shot selection is uncanny. He knows when and he knows when not to—as illustrated by his .555 field-goal percentage over the past two seasons. His .574 accuracy in 1987-88 ranked as the second-best percentage ever by an NBA guard and placed fourth in the league that season. His .538 last season was 10th best in the league, and he was the only guard on the top 10 list.

This double jeopardy approach to the game—will he pass or will he shoot?—is simple but highly effective. The recent history of the NBA’s Good Hands Award, sponsored by Allstate Insurance, suggests just how effective. The award, based on a formula that involves points, assists, steals, rebounds, and turnovers, is designed to recognize the top point guards in the league. It is given monthly and yearly. Over the past two years, Stockton has won it 12 of a possible 12 months, and two consecutive years.

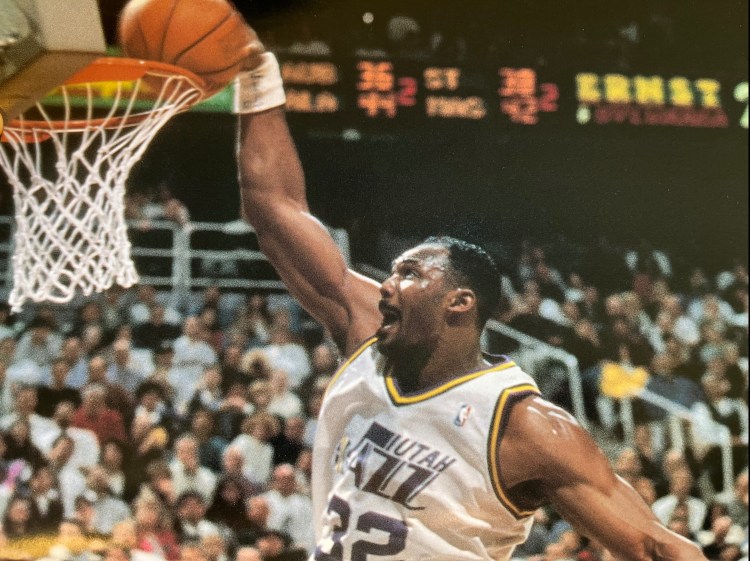

Of all people in the universe, it’s Malone who is most aware of the above. How aware? Aware enough to threaten to boycott last February’s All-Star Game if Stockton wasn’t also invited. Either that, The Mailman suggested, or he’d wear Stockton’s No. 12 as a sign of protest. When Stockton was selected by the coaches—after being snubbed by the fan balloting—the protest didn’t have to happen . . . and, with Stockton at his side, The Mailman was on his way to becoming the All-Star MVP.

To tell Karl Malone from John Stockton, look for the guy who’s on the other end of Stockton’s passes. More than half of Stockton’s assists go to Malone, and well more than half of Malone’s points come from Stockton assists. Stockton gets things started. Malone gets them finished. It’s not hard to understand his meaning when The Mailman says, “Anyone messes with Stockton, messes with me.”

Messing with Malone requires roughly the same level of intelligence as walking into Gold’s Gym and liberally throwing around the word “wimp.” The Mailman is not a turn-the-other-cheek type of individual. He made that point quite clearly his first year in the league, in 1985-86, when, from the get-go, he was no respecter of persons. Go ahead, name a superstar. Malone ran into him.

There was one memorable confrontation with Maurice Lucas, the noted enforcer. Lucas put an intimidating offensive move on the rookie, complete with the patented Lucas glare. On the other end, Malone got the ball, slam-dunked over the top of Lucas and screamed, “No one intimidates me!” Then, after the game, Malone said how much he admired Maurice Lucas.

Ever since, it’s been one dragon-slaying after another. At 6-foot-9 and 256 pounds, Malone is one of the more imposing athletes anywhere. When Mike Tyson showed up at Magic Johnson’s All-Star Game in L.A. a year ago, it was The Mailman that The Champ wanted to meet. Malone is, in most respects, the direct opposite of Stockton. What you see, is what you get. He looks like he should play a power game, and he does. He is not timid about going to the glass, or about rebounding. His 29.1 scoring average last year was second only to Jordan’s 32.5, and his 10.7 rebounding average was behind only Hakeem Olajuwon, Charles Barkley, Robert Parish, and Moses Malone.

He was the only NBA player to rank in the top five in both scoring and rebounding, and he did it for the second season in a row. Malone went to the free-throw line (918 appearances) more than anyone last season, including Jordan—a statistic that reflects the increasing respect he’s getting in the league. From referees, especially. Just two seasons before, while playing almost the same amount of minutes, Malone went to the free-throw line just 540 times.

But he is like Stockton in one respect. He is a lot faster than he looks. Or, as Sloan says, “He’s 6-9, 250, and he can move. He’s one of the better runners in the game at the four position. He can be behind somebody and get past them in a hurry. And when he gets out on the break and Stockton’s looking for him . . .”

Even the stoical Sloan shows a hint of a smile when he lets that statement hang. As Stockton is quick to point out, “Karl Malone is one of the best finishers in the game. And when you work with someone every day for several years, you’re going to get a lot better at knowing what you’re each going to do at any situation.”

That’s the other imposing part of The Mailman’s game. He keeps getting better. Every season he has surpassed his previous season. As Lakers coach Pat Riley noted in an interview, “He’s the best power forward in the game right now . . . and I just hope he doesn’t get any better. I don’t think there’s ever been anybody chiseled like Karl Malone, who can do what he does.”

Or, as the Converse Company, whose shoes Malone wears, was proud to announce in a full-page nationwide magazine ad after last year’s All-Star game: “Neither Rain, Nor Snow, Nor Sleet, Nor Michael, Nor Charles, Nor Moses, Nor Dominique . . . Nothing could stop Karl Malone in this year’s NBA All-Star Game. Congratulations to The Mailman, who now carries letters that read MVP.”

****

All this, from two guys at least half the league could live without.

They came to Utah a year apart—and with similar anonymity. Fifteen franchises passed on Stockton in the 1984 summer draft before the Jazz picked him up. The next summer, a dozen franchises passed on Malone before it was the Jazz’s turn to choose.

Neither one had a can’t-miss tag. They were as obscure as the places they came from—Stockton from Gonzaga University, a private institution of 3,800 students located just a mile or two from where he grew up in Spokane, Wash.; and Malone from Louisiana Tech, a public institution of 10,200 students located 40 miles from where he grew up in Mount Sinai and Summerfield, La.

The first thing Stockton did after he discovered he’d been drafted by the Jazz was to write to the team’s offices and ask for videotapes of Jazz games. He wanted to know the offense before he came to rookie camp, and he wanted to study the game of the Jazz’s starting point guard Rickey Green.

Stockton elevated himself to first-round draft status with a similar work ethic. Or, in his case, call it a play ethic. From the first time he was introduced to a basketball in grade school, he couldn’t put it down. When his grade school coach offered to open the school gym at 6 a.m. every morning, if anybody wanted to play before school, Stockton took him up on it. Every morning.

His older brother by four years, Steve, helped hone him competitively—taking him downtown on the driveway basketball court for as many years as possible. Stockton’s life was simple enough in Spokane, revolving around the three Catholic schools that saw him through his education—St. Aloysius Elementary School, Gonzaga Prep, and Gonzaga U.—and around their gymnasiums.

In March of 1962, 10 days before John was born, his father, Jack Stockton, along with Dan Crowley, bought a Spokane neighborhood bar. They named it Jack & Dan’s, and it still stands on Hamilton Avenue, next to University Pharmacy. It has become a Jazz outpost in Washington. There, you can get a beer in a souvenir Jazz mug, and on Jazz game nights, the TV above the bar will be tuned in via satellite.

In summers, John and his wife, Nada, and their two children retreat to Spokane, where John has bought the house next to his parents, and where he plays on the Jack & Dan’s softball team. In most ways, he has moved only slightly from his roots. He is still outwardly shy, though cordial enough. He doesn’t seek out publicity. Indeed, he still stays true to a college habit of not reading newspaper articles about himself. He prefers to not be tempted to get caught up in himself or other trappings or hype.

It’s always been his game that does his talking. In college, he was the MVP of the West Coast Athletic Conference his senior year. Since the WCAC isn’t exactly the mainstream of American college hoops, that didn’t make him a household name. But it did get him invited to the postseason all-star games and to the Olympic team tryouts (where he survived to the final 20 before he was cut). His NBA stock started to slowly rise.

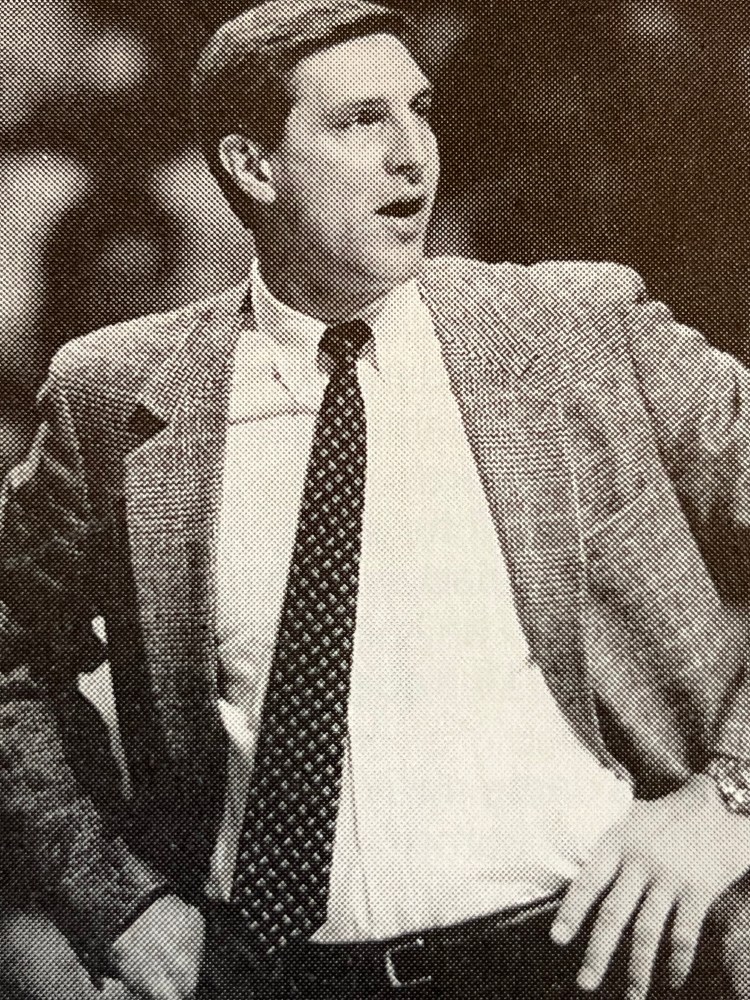

He came to the Jazz’s attention when special Jazz scout Jack Gardner—the Hall of Fame college coach from Kansas State and Utah—saw him play during his senior year of college. With Rickey Green in his prime and just coming off an all-star season in 1983-84, the Jazz weren’t necessarily, looking for a point guard with their first-round pick.

But Gardner said he’d stake his reputation, which was considerable, on Stockton. When Frank Layden and his assistant coach son, Scott, saw Stockton later in an all-star game, they concurred. For almost two months, until the draft in June of 1984, the Jazz kept their thoughts on Stockton under wraps. He was their well-guarded secret. So well-guarded that when he was announced as the Jazz’s first-round selection, and 16thplayer taken overall in the draft, the 5,000 Jazz fans listening to the news in the Salt Palace asked, “John Who?”

The next June, when Malone was taken by the Jazz as their first-round pick, and the 13th player taken overall, the Salt Palace reaction wasn’t quite as subdued. More people were aware of The Mailman, since he was, after all, a 6-foot-9, 250-pound specimen who had broken two backboards in college, and he’d been the subject of a glowing Sports Illustrated story.

Still, he was leaving college a year early and, beyond his imposing size, he was something of a mystery man. People in Utah barely knew more details about him than he did about them. When he spoke in Madison Square Garden on draft day, he said he was looking forward to playing for the “town of Utah.” Further, he was crying when he said it, happy and relieved to have finally been selected. Malone is nothing if not emotional. He lives his life that way, and he plays basketball that way. And when he was growing up in Mount Sinai, La. (pop. 250), he got in trouble that way. As he recently told writer Peter Knobler, “From when I was 12 till 17, if I went a day and a half without getting a whupping, something was wrong . . . If I didn’t get a whupping, I just couldn’t sleep at night.”

Shirley Malone Turner, Karl’s mother, administered his whuppings. But she did more than that. She raised her family of eight children by working three jobs, and then she’d become a human backboard for Karl to shoot baskets at in the evening when she was home. She was Karl’s inspiration, and remains so. He still calls her before or after many Jazz games, and, like Stockton, Malone goes close to home in the summers. He lives in Dallas, which is close enough to drive home often for Shirley’s cooking.

Shirley and her second husband, Ed Turner, run a country store in Summerfield, La. Last February, they closed it down long enough to drive to Houston for the All-Star Game, where they found themselves on nationwide TV at the finish, hugging Karl, the MVP. The Mailman thanked his mother and stepfather and said he’d put Utah on the map. “A lot of people don’t know where Utah is,” he said on television. “But they will now—it’s in Salt Lake City.”

At any rate, he’s getting closer on his geography, and the Jazz never worried about that part of his education. When scouting him in college, what they liked was his rebounding and his drive. He averaged 9.3 rebounds per game for his career at Louisiana Tech, plus two shattered backboards. When he signed on as a freshman and discovered he couldn’t play ball because his high school grade point average of 1.97 was .03 below eligibility standards, he dug in and became a 2.6 GPA student as a non-playing freshman.

That’s the Malone intangible—an insatiable desire to right the tables, to come out on top. The kind of competitor who will shoot 48 percent from the free-throw line as an NBA rookie. The kind of competitor who then hired shooting coaches and practiced till his fingertips get sore in the summer. The kind of competitor who improved to 59.8 percent his second year, 70 percent his third year, and 76.6 percent in 1988-89, when he shot more free throws than anyone in the NBA.

****

After nine years now in the NBA—five for Stockton, and four for Malone—logic suggests that their prime is just beginning. But their somewhat meteoric rise to prominence and success were derailed slightly in the playoffs of 1989. After considerable playoff success in 1988, climaxed by a seven-game series with the Lakers, and after their one-two MVP finish in the All-Star Game, they and the Jazz were leveled in the first-round of the Western Conference playoffs by the Golden State Warriors.

Warriors coach Don Nelson exploited the Jazz’s relative team slowness, spreading the court away from the Jazz’s 7-4 defensive ace Mark Eaton. That cut down on the Jazz’s outlet passes and on Malone and Stockton’s tandem fastbreaking effectiveness. The Jazz were swept in three games. Their rematch with the Lakers never came to be.

All of which sets the stage for a redemptive season of sorts for Malone and Stockton (and the Jazz) in 1989-90 and keeps the jury sequestered as to their niche in NBA history. For all the extraordinary statistics to date, and their six-figure annual incomes, and their odds-defying rises from obscurity, they have yet to lead their team to anything more than a Midwest Division title.

“There are two guys who take losing very seriously,” says Sloan. “I’d expect they’ll come back, ready to play and improve even more.” Which is precisely what Pat Riley—and a lot of other rivals in the NBA—don’t want to hear. Stay tuned. If the Stockton-Malone pairing improves any more notches, the Jazz will have less and less free time in the summer on their hands.

[The Phoenix Suns would upset Stockton, Malone, and the Utah Jazz in the first round of the 1990 NBA playoffs. Like Michael Jordan and the Bulls, Utah would have better luck in the postseason a few years later.]