[This post was meant to feature former NBA star Mychal Thompson, Klay’s dad. But then I got distracted. I got distracted with Thompson’s iconic New York-based agent, Irwin Weiner, now almost 23 years in the grave. The red-headed Weiner, a lookalike for comedian Red Buttons, was a truly unique character and a pioneer in player representation, renowned for his colorful negotiating style and at times brilliant promotional skills. “Total management,” he called it, making a point to loudly loathe the word agent. “I am not an agent,” Weiner frequently scolded. “I believe in total management. I do more than negotiate fat contracts. My responsibility is to plan and build for the player all the way—on and off the playing field.”

Or, as many an owner grumbled, Weiner’s total management style was a recipe for chaos. “Weiner comes every year to renegotiate every contract,” lamented Nets’ owner Roy Boe. “It’s on a continual basis, so I deal with that every year.”

Weiner got his feet wet in total management by dumb luck in his late 30s. He had a chance meeting with New York Mets star Ed Kranepool. That connection put him in touch with New York Jet running back Emerson Boozer and then, momentously, with the Knicks’ flashy-but-shy star Walt Frazier. Weiner and his big personality seized the opportunity to serve as Frazier’s squinting, half-blind driver and eventually his business partner. “Wonder,” Frazier called him, and W.F. (Weiner-Frazier) Sports Enterprises was what they called their total management business.

By the mid-1970s, W.F. Sports Enterprises represented a formidable 150-plus stable of pro athletes, including Julius Erving and George McGinnis. Though Weiner would have a falling out with Frazier, he boldly shilled on as only he could, an ever-present cigar smoldering in hand, through the 1980s and into the 1990s.

Long story short, the Mychal Thompson post has morphed into a remembrance of Irwin Weiner, though Thompson does make a few guest appearances. As you’ll see, I’ve stitched together several articles about the influential Weiner’s many irons in the NBA fire from the spring and summer of 1978. The stories offer a nice intro into Weiner and a telling snapshot of the sports representation business during the late 1970s. To get things started, let’s time travel to a March 2, 1978 column in the New York Daily News by the great Mike Lupica. As one of its subheads rightly reads: King of Renegotiation. That was Weiner.]

****

On the wall over his head were bullhorns, and stuck on the end of each horn was a dollar bill. Appropriate. In his business, bull makes money. Irwin Weiner sat at the huge round conference table that serves as his desk. When he set down the receiver of his phone, the soft lights of his plush office reflected off a monstrous diamond ring set in gold that covers most of the third finger of his left hand. This was the modest corner of W. F. Associates, where Irwin works.

From here, he sends his mouth and his street smarts into action to make money for athletes, and for himself. Irwin loves the action, but this morning he was mad about the Lenny Randle incident with the Mets, for one thing.

“A set-up,” said Weiner in his voice which is from 116th Street and 1st Avenue. “The whole thing smells like a set-up. I read now that Randle’s takin’ the rap himself. But this whole thing looks to me like an agent (Gary Walker) pushin’ a player. He pushes him into tryin’ somethin’ like this, and then he lets him hang out there for a couple days before pullin’ him in. Now people forever will be lookin’ at this Randle like he’s an ingrate. An agent who lets this happen to somebody is a schmuck.”

Irwin, who started his firm with Walt Frazier, and now manages such athletes as Julius Erving and George McGinnis in a multi-million-dollar business, which takes up the entire 17th floor of a Lexington Avenue building. He is the king of renegotiation, which Randle was trying with the Mets and is the new national pastime. Irwin admits this. But he also says he picks his spots, he’s never hurt a client by trying it, and he never tried it with an owner who didn’t know it was coming.

“I’m known for breaking contracts,” said Weiner, waving a long cigar that he said cost a dollar. “But we’ve always let these things be known at the outset, y’ see. If they want to lock up one of my guys long-term, for security reasons, then ‘Fine,’ I say. But I also tell ‘em we’ll be back to renegotiate. Now you can’t have that written into the contract ‘cause no commissioner’s gonna go for that. But they know. Roy Boe, he knew it was that way with Erving. If he didn’t want it that way, we woulda signed a short-term deal, and I woulda fought him for every penny. But remember I was dealin’ with Julius Erving there.”

Weiner, who is tough and not stupid, said yesterday that when Erving was holding out last fall before going to Philadelphia, John Williamson came to Wiener and wanted to try the same thing. “I kicked his ass out of the office,” said Weiner. “I told him he was in no position to stay out of camp. He left the office mad as hell. But when he cooled off, he calls and he says to me, ‘Irwin, you were right. I ain’t like Doc. It’s a different situation.’ Bottom line? It woulda ruined his career. Now he’s got the big contract and sits pretty.”

This is what happens everywhere now. Naïve athletes get bad advice from agents, and careers are ruined or damaged. Randle is back with the Mets and his career goes on, the people will never forget that a player who beat up a 53-year-old man and was nearly out of baseball came back the next year and wanted a new contract.

Brian Taylor had a $300,000 contract to play for the Denver Nuggets; he walks out on them on the advice of an agent Abdul Jalil, saying they have reneged on certain bonus clauses.

Tom Skladeny comes out of Ohio State and does not like the contract offered him by the [football] Browns. So he sits out a year so he can go back into the draft. It is said by his agent Howard Slusher that Skladany has principles. The question is, whose?

“Everything is timing, thinking,” said Weiner. “Now you gotta have talent. But you gotta think, too. When you take a shot with a Randle or a Skladany or a Taylor, you better know the market and what your options are. ‘Cause if you taka e shot and you’re wrong, maybe you kill a guy. Jalil comes along and fills Taylor’s head with great visions. But Taylor’s a guard in a year when good guards are out of work. So he sits, and Denver goes on without him. Skladany? How’s he ever gonna make up for that lost year. He can’t. No way. He’s been damaged.”

It happens more and more often this way, and it makes you sick. Weiner is no saint, but at least he takes care of his people. He never would’ve let the Randle thing happen.

“These are terrible thing happenin,’” said Irwin Weiner yesterday, the big ring glittering, the left hand holding the cigar. “They’re givin’ the business a bad name.” Above him, money hung on the horns of the bull.

[Let’s go next to Weiner’s client, George McGinnis. As stated in this article, from the June 6, 1978 issue of the Philadelphia Daily News, McGinnis’ days in the City of Brotherly Love are suddenly numbered. Here’s Phil Jasner on the call. Note, I’m copying here only the relevant first half of Jasner’s story.]

Yes, George McGinnis still has a no-trade clause in his contract. No, he has not agreed to any arrangement that would send him back to the Indiana Pacers. But if the 76ers are actively pursuing a deal with Indiana (and they are), what would it take to convince McGinnis to waive the no-trade clause?

‘Easy,” said Irwin Weiner, McGinnis’ agent and business partner. “It would take three things: first, for Philadelphia to guarantee the existing contract (the three remaining seasons); then, for the contract to be extended two years; and then for George to get some financial compensation (a cash outlay of, say, $50,000).

“The point is, we came to Philly with a no-trade clause as a protection for George. He wouldn’t now ask for a new contract or a raise . . . he’s said he’s unhappy with the contract he has. But he has also lived up to his end of the agreement.

Now, for him to move his family, take his kids out of school, sell his house . . . I don’t think you can ask him to just pick up and move without compensating him in some way.”

But haven’t the Pacers recently been refinanced? And haven’t they come up empty in their attempt to lure Indiana State hero Larry Bird away from another year of college eligibility?

“Being refinanced,” said Weiner. “What does that mean? Three weeks ago, their checks were still bouncing. Does being refinanced now mean another 3 to 5 months? More? Less? That’s obviously why we’d want Philly to guarantee the contract if George went back there.”

“We want Indiana’s pick (the first choice in the first round of Friday’s college draft),” said Pat Williams, the Sixers’ general manager. “But all is quiet on the Western Front. It’s heating up, sure, but it’s heating up because of the time factor. Indiana hast to make up its mind. I’m not gonna say definitely that we’d take (North Carolina guard) Phil Ford, but we think there are two premier picks in the draft . . . Ford and (junior-eligible) Bird. These two are a cut above.

“After them come (Minnesota’s) Mychal Thompson, (Kentucky’s) Rick Robey, (Las Vegas’) Reggie Theus, (Marquette’s) Butch Lee, a few others. Ford and Bird are at the top.”

Williams admittedly spent the weekend trying to finalize something with the Pacers. “Today . . . tonight . . . tomorrow, I doubt it’s gonna happen that quick,” he said. “It’s more likely to drag.

“Indiana might wait until Friday morning. They’re extremely interested in George, and I doubt that anyone around the league can make them a better deal for that pick than we can. From our end, we’ve talked to just about all the teams, but I don’t see anything significant right now with anyone, but Indiana.”

[Fast forward a few weeks, and the McGinnis saga continued. McGinnis was now headed to Denver. Or was he? That was the question asked by reporter Dick Weiss. He started his story, which ran in the June 20, 1978 issue of the Philadelphia Daily News, by going to the source: Irwin Weiner.]

Irwin Weiner, George McGinnis’ agent, met with members of the Philadelphia 76ers’ front office to discuss alimony payments. The New York-based attorney reportedly is asking the Sixers to pay McGinnis close to $200,000 if they want the powerful 6-8 forward to sign a release waiving the no-trade clause in his lucrative multi-year contract.

Big bucks? You bet.

But Weiner may have [owner] Fitz Dixon and the rest of the bluebloods right where he wants them in this complicated business deal that would send George to Denver for Bobby Jones and Ralph Simpson.

The Sixers have no qualms about openly admitting, they want to get rid of McGinnis, offering him first to Indiana for the top pick in the college draft and then, when the bid for Phil Ford fell through, offering him next to Denver for a defensive-minded forward they felt would blend in better with Julius Erving (also represented by Weiner).

Just two weeks ago, when the NBA draft was held, Sixers’ general manager Pat Williams was quoted as saying, “We have an unspoken agreement with Denver—not a trade.”

Yesterday, Williams was saying, essentially the same thing. “No trade yet,” he claimed. That is about all that came out of the Sixers’ front office, leaving clues to the effect that the deal could be this much as a week away from finalization.

Or, even worse the deal may be in jeopardy.

*****

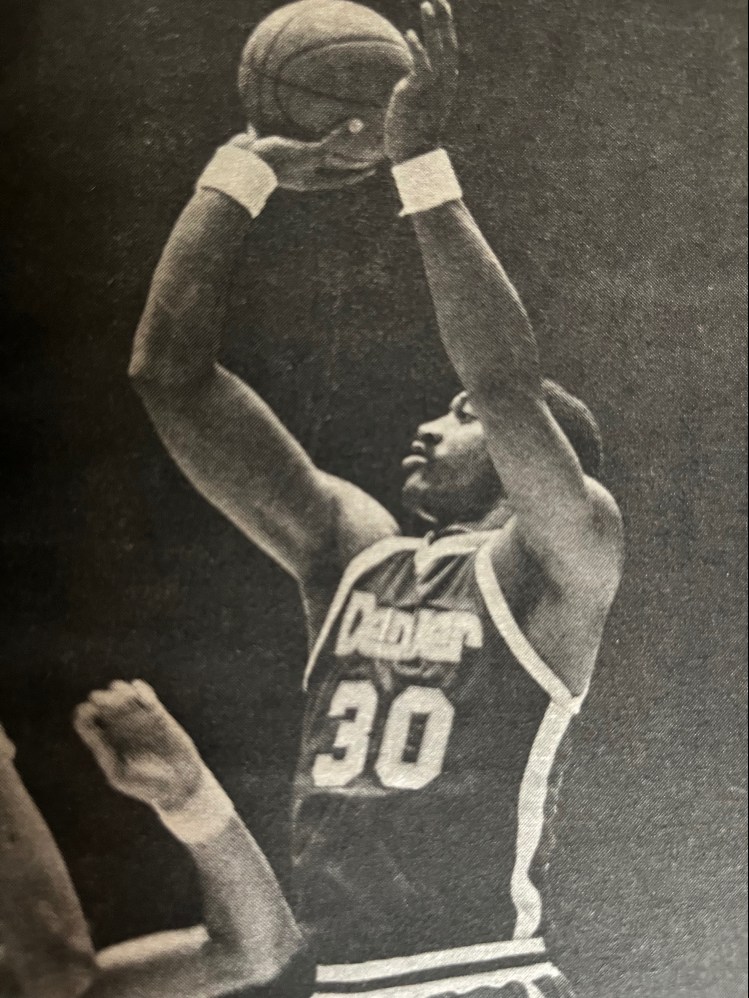

[While Weiner hunted for another home out West for George McGinnis, he tried to land the right starter home in Portland for Mychal Thompson, the top pick in the 1978 NBA Draft. Weiner runs through the latest rigamarole in his negotiations with the Trail Blazers and more with Augie Borgi, a New Jersey kid gone West to write for The Oregonian. Borgi story ran on July 26, 1978 under the headline: Thompson Wants More Money.]

Today’s episode in the Mychal Thompson-Irwin Weiner-Portland Trail Blazers triangle started when Weiner placed a call to Portland. (It should be stressed that Weiner—as in hot dog—likes to brag: “Tell him to call me. I don’t return calls, you know that.”)

Weiner also had some news: George McGinnis has been traded by Philadelphia to Denver for Bobby Jones. Back to the news after the commercial from Irwin Weiner.

“I’ve never been down to Portland,” Weiner said. “When I come to town, they’ll give me the red-carpet treatment. It will all be blood.”

Irwin Weiner talks New Yorkese. He was speaking from the plush office at W.F. Sports Enterprises. In New Yorkese, Portland is down there somewhere in the geographic sense, not out there. But geography is not Irwin Weiner’s concern right now. Money is his only concern.

“We’re apart on money—way apart,” he said. “We’ve got the no-cut situation settled and certain other things that I don’t want to go into. They’ve been discussed and settled. But I’ve got to move. I’ve got to realize the top players are going to get more money this year than last year.”

Why?

“Because (Kent) Benson was represented by a former general manager (John Erickson) who is not a negotiator, and now they’re dealing with me—the best.”

What makes you best, Irwin?

“I’m still the best, from Julius to . . . Look at the deal I got for George McGinnis from Denver. An extra million-two ($1.2 million), maybe even an extra million-four, just on a no-trade clause that we took out of the contract so that they could trade him to Denver. That news will come out later this week,” Weiner promised.

But what about the Blazers and Mychal Thompson, the No. 1 draft pick? And why does Weiner think Thompson is worth more than Benson, other than that Benson had the lowest rebounding percentage (based on minutes played) of any center in the National Basketball Association last season?

“Last year has nothing to do with this year,” Irwin said, “Look, (Donald) Dell has the second guy, who do you call it, the name is on the tip of my tongue—Phil Ford. And (Larry) Fleisher has Butch Lee, and look at what Fleisher did for David Thompson. But that was really nothing compared to what I did for McGinnis. An extra million-four just for a no-trade clause.”

Irwin Weiner and the Blazers understand the no-cut part of contracts perfectly. “I did Herm Gilliam’s contract (an estimated $125,000), and he was protected on no-cut and he got paid for the whole year,” Weiner said.

“What do you think of T. R. Dunn? He’s one of my players, and he got another year of no-cut. They (the Blazers) don’t want him, but he’s got to get paid another year,” Weiner said.

Now comes the time for the Blazers to pay Thompson or for Weiner to accept what Portland is offering. “You think (Portland center) Lloyd Neal is all right? I don’t think so, and Mychal, he can play two positions.”

Irwin Weiner is not a doctor, but he will use every edge to improve Thompson’s bargaining position. “I hope we can sign before camp,” Weiner said, never mentioning that the Blazers’ management would have liked Thompson to have learned something about the Blazers’ system in the summer league. “But I don’t want to say we won’t sign by then. I hope they get out of the middle.

“I spoke with Stu Inman (Portland’s director of player personnel), and I can’t judge him yet. I met with Larry Weinberg (the Blazers’ owner), and he seems to be a nice guy. I found him to be a nice guy. He’s from Brooklyn.”

Welcome back, welcome back, welcome back to New Yorkese. Weinberg can understand Weiner, and Weiner can understand Weinberg. No language barriers. It comes down to Weinberg’s checking account and the hope that Memorial Coliseum may be expanded by 4,000 seats so that the Blazers will be able to realize a bigger and better profit, even after bigger and better player contracts.

It’s easy to say who should pay Irwin Weiner’s and Mychal Thompson’s demands. Larry Weinberg should pay. How much he should pay is something else. “I told him yesterday that they should get off the middle and call me,” Weiner said.

[Now for more on the McGinnis trade and his unhappy parting of ways with the 76ers. Irwin Weiner had finally enriched McGinnis enough to move him to Denver so that his other top client, Julius Erving, could shine properly in Philadelphia. Here’s more from the fantastic Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Frank Dolson. His column ran on August 17, 1978.]

At the end George McGinnis was a bitter man, a disillusioned man, and that’s a shame, because few athletes in this town have ever been accepted so warmly, so generously by fans and media alike.

He came here as the Three Million Dollar Man who was supposed to restore pro basketball to major-league status in Philadelphia, and, in that, he succeeded. Don’t underestimate the importance of McGinnis’ arrival. “I think that was the point that pro basketball turned around in Philadelphia,” Pat Williams, the general manager of the 76ers said yesterday at the press conference called to officially announce McGinnis’ departure.

But if McGinnis put the 76ers on the map, if he provided them with almost instant respectability, he did not carry them to the very top of the mountain. The 76ers’ frontcourt, it turned out, wasn’t big enough for two offensive-minded, crowd-pleasing superstars. “George and Julius (Erving) tried so hard to complement each other,” coach Billy Cunningham said. “I just don’t think they were able to do it.”

One of them had to go. For more than two months, it had been obvious that George was the one. Sadly, he left, screaming and kicking and complaining, not the way you would’ve expected George McGinnis to do anything. At almost all times during his three years here—even those very rough times in the playoffs—he handled himself with dignity and class. And he was treated with dignity and class.

“He began developing a following of fans, the likes of which I never saw in the city,” William said. “You think of all the athletes in this town who went through bad times and were ridden out of town on a rail. It never happened with George, which I think is remarkable.”

What did happen, though, was that the Three Million Dollar Man outlived his usefulness here. Throughout his career, teams had begged for his services. College teams, pro teams, all sorts of teams. Suddenly, he was on a team that didn’t want him . . . and it hurt.

The pain, the injured pride, call it what you will, was most evident Tuesday when McGinnis held his last pre-trade meeting with the 76ers on the 20th floor of United Engineers Building in downtown Philadelphia. “Everybody was there but Denver,” Williams said, explaining that McGinnis’ new team had already mailed a contract.

“Everybody”—included McGinnis, his agent Irwin Weiner, Weiner’s attorney Ed Deutsch, Williams, and the 76ers’ attorney Peter Matoon. For five hours they met and talked and waited for George McGinnis to sign the piece of paper that would permit the 76ers to trade him.

“I saw a George McGinnis I never saw before,” Williams said. “(I saw) a hostile George McGinnis. Hostile to me as a symbol of the 76ers, I guess. He was glaring. His teeth were grinding. He was an angry young man. I think the bottom line is that he didn’t want to go. If the deal collapsed, it would’ve been all right.”

All right with George. Not all right with the 76ers.

“He knew we didn’t want him anymore,” Williams said. “The amazing thing to me, three years ago, he didn’t want to come to Philadelphia. Then, because of money, persuasion [including from Weiner], the state of the American Basketball Association, he came. Now he didn’t want to leave . . . I think he’s very upset, very distraught. He’s embarrassed. His pride is hurt. This is the first time in his life that he was told somebody didn’t want him. When he was in high school, 300 colleges were after him. The Knicks wanted him so much, they signed him illegally. We chased after him. Now, at age 28, he’s been rejected. I guess it stung him. It wounded him.”

It prompted him to say the things he’s been saying these final days before the trade . . . and to act the way he did in Tuesday’s long, hard meeting with Williams and the attorneys. For a few fleeting minutes, the 76ers’ GM found himself wondering if McGinnis would ever sign that piece of paper. “I called George at one point during the summer,” Williams said, “and he told me, ‘I’m prepared to come back (with the 76ers).’ He meant it.”

But the 76ers weren’t prepared to take him back. For George McGinnis, the superstar who restored pro basketball to major-league status in Philadelphia, it was a tough way to go.

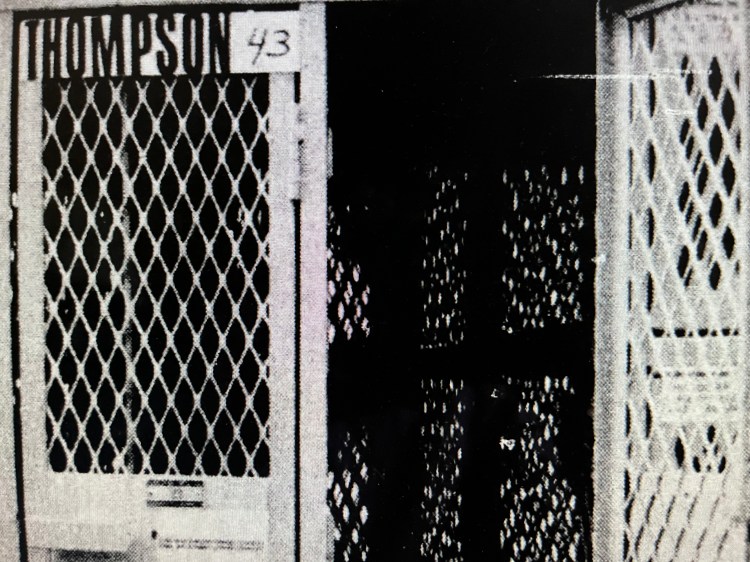

[“Down there,” as Weiner called it, in the Pacific Northwest, he finally struck an attractive deal for Mychal Thompson to join the Portland Trail Blazers equitably. The University of Minnesota All-American would be in camp shortly to replace the departing Bill Walton. The Blazers’ hobbled big redhead had declared his desire to play elsewhere with an upgraded medical staff. To tell us more about Weiner and mostly Thompson’s long journey into the pros is the Minneapolis Tribune’s Jon Roe. His story appeared on September 13, 1978.]

For more than a year, the telephone would start ringing at 7 a.m. and wouldn’t stop until after midnight. Mychal Thompson’s roommate, Bill Harmon, used to invent stories about why Thompson couldn’t come to the telephone. Seemingly everybody whoever called himself an agent—Thompson estimated there were more than 40 who wanted to represent the University of Minnesota All-American—had to a deal to offer.

The marathon ended Tuesday in Portland when Thompson signed a contract with the NBA Trail Blazers for a reported $1.3 million over five years. “I’m glad it’s all over with, sighed Thompson. “Now I can think just about playing basketball. I knew it would probably take this long, and I was willing to wait. But it has been quite an experience.”

The experience started near the end of Thompson’s junior year. He had been the central figure in the NCAA probe into Minnesota’s basketball program. Thompson had said that he sold two season tickets for more than face value two years before, and he had finished his sophomore, season playing under a court order. When his junior year was over, he considered turning pro via the NBA hardship draft.

“When I said I was considering turning pro,” said Thompson, “the phone started ringing. Calls from New York to L.A., at all times of the day. Each one said he could get more money than the last guy who called. Some were even willing to loan me money right away if I wanted it, but those are the ones I turned down first.

“When I decided not to turn pro, to come back for my senior year, the calls stopped. But just for the summer. They started in again last fall. Bill (Harmon) had to make up stories to get rid of all the callers. He would say I had just stepped out of our apartment a few minutes before. Or that I was in the shower. Or that they must have a wrong number.”

Thompson’s father, DeWitt, was suffering through the same ordeal at the Thompson home in Nassau, Bahamas. “I don’t know how many people called,” said the elder Thompson. “If Mychal says it was more than 40, he’s probably right. I just know it was a lot. Of course it was a hassle. But I always felt that Mychal is a person who can cope. And both of us knew what kind of a person we were looking forward this year to represent Mychal.”

It turned out to be Irwin Weiner, a well-known agent in New York. On the surface, however, Weiner seemed an unlikely choice. “At first,” said DeWitt Thompson, “I was taken aback by Mr. Weiner. He was somewhat brash on the outside and not a bit reluctant to say what he had been able to do for other athletes who were clients of his. Other agents have been just the opposite of that, very pleasant, very modest.

“And there had been a lot of agents and other people who had knocked Mr. Weiner. That was something that I didn’t especially like. Whenever one agent said something against another agent, I checked him off as the man for Mychal. I can show you the records I kept where I actually put a check next to the man’s name to show that that wasn’t the man we wanted.

“I tried to offer as much counsel to Mychal as I could. When I went to New York to meet with Mr. Weiner, I unhesitatingly knew he was the right person. He is involved in so many humanitarian projects (mainly for vision research) that I just knew he couldn’t be the kind of person others were saying he was.”

Mychal Thompson had all the endorsement he needed when Julius Erving, the superstar of the Philadelphia 76ers, said Weiner was his and was the agent Thompson needed. “Irwin had the track record that showed he knew how to get the top dollar,” said Mychal Thompson. “But he also was a first-class guy.

“He knew what to do in negotiations, but he also knew how to plan things out for me for the future. There was no way that I could ever understand all the things that go into a contract, but he could rattle things off like nothing.”

Now Thompson embarks on his pro career. He has been practicing with the Portland rookies for two days and will have another week before his first exhibition game in Seattle. With the expected departure of center Bill Walton, Thompson’s negotiating position was strengthened, but it also means he has to learn to play both forward and center.

“I hope I can live up to my expectations and the expectations of everybody else,” said Thompson. “I’ve still got a lot to learn about the pro game, but it’s coming along and I think that I’m a quick learner.”

He has learned a lot in the last 18 months.