[Nate Thurmond remains one of the all-time great NBA centers and an iconic Golden State Warrior. However, he didn’t age gracefully jostling the NBA giants in the post night after night. By his early 30s, foot and knee injuries had slowed Nate the Great, and the Warriors entertained trade offers for the former cornerstone of the franchise in the spring of 1974.

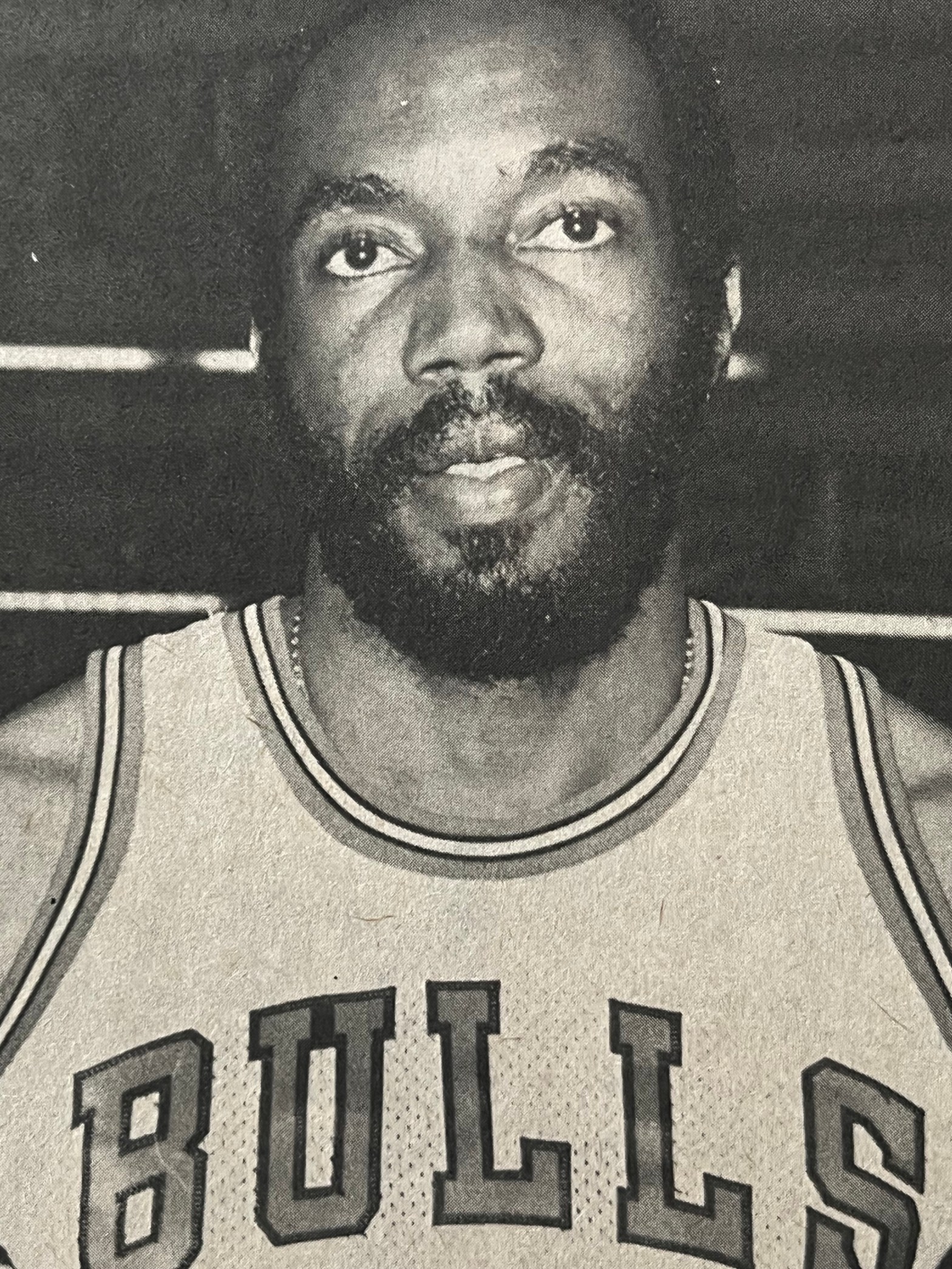

By that summer, the Warriors had received a firm offer from Chicago coach Dick Motta, and Thurmond became a Bull about a month later in exchange for the young, athletic, but offensively-challenged center Clifford Ray and, important back then, lots of cash. As writer Dave Newhouse notes below, Motta considered Thurmond, his chronic injuries aside, to be the dominant veteran center that his Chicago teams had always lacked. Or, as Newhouse put it: Thurmond would be the final piece in assembling Motts’s NBA championship machine for the 1974-75 season.

It sounded good when Newhouse wrote his piece. But Thurmond failed badly in the Second City. He couldn’t get comfortable running Motta’s methodical offense, and coach and center never quite saw eye to eye. In fact, when Newhouse’s article hit the newsstands in March 1975, Thurmond was well on his way to logging near career-worst averages for points (7.9 per game), field-goal percentage (36 percent), and rebounds (11.3 per game). Of course, the irony was the Warriors, starting Motta-reject Clifford Ray in the middle, would win the 1975 NBA championship.

By the start of the 1975-76 season, Thurmond had threatened to retire, then refused in late November to dress for a game to avoid answering the chorus of questions about his impending departure. The Chicago newspapers had reported the day before that the Bulls planned as soon as humanly possible to unload Thurmond—and especially his then-hefty $350,000 annual salary.

“Soon” turned out to be a few days later when Cleveland took Thurmond, an Akron native, off Motta’s hands along with reserve swingman Rowland Garret in exchange for the lower-paid backup center Steve Patterson and rookie forward Eric Fernsten.

“Nate was a distinct disappointment to us,” Motta said of the Thurmond experiment. Thurmond said roughly the same of the fiery Motta. “Motta’s killed my spirits, and I don’t think I can play under these conditions,” he said on the eve of the Cleveland trade. “If they want to get out from under my salary, I hope a trade or something can be worked out. I don’t want to be the third center. My floor time is down to nothing . . .”

Despite Thurmond’s nightmare in Chicago, Newhouse’s article about his presumed long stay there still has its merits. The article offers a timely check-in on Thurmond after his long Golden State tenure and tells why he left his heart in San Francisco. The article, published in the March 1975 issue in the magazine Pro Sports, also provides a clear look into the mind of Motta and his attempt to build a pretty darn-good machine in Chicago with legends Chet Walker, Bob Love, Jerry Sloan, and Norm Van Lier.]

****

There is no star system with Dick Motta. He doesn’t look at his players as six-figure athletes with double-figure statistics. They are simply parts to a machine. This machine: the Chicago Bulls.

Whenever a part of that machine malfunctions, Motta sends out for another. You see he demands—call it bullish—precision at all times. Anything less will drive him up a wall . . . or a referee’s neck.

It is generally accepted in the National Basketball Association that no one, but no one, has a more precision machine than Motta, even though other teams have parts which are better known and cost more. A Jerry Sloan is less expensive than a Nate Archibald. A Chet Walker or a Bob Love isn’t worth as much on the open market as a John Havlicek or a Spencer Haywood.

Motta’s machine has won 50 or more games each of the last four seasons without one first team All-Pro. Getting more out of less, one would think, would be a source of satisfaction to Motta. Only he was still searching for the one spare part that would make his machine more feared than respected. He found it in Nate Thurmond.

Thurmond would be more than just a part in NBA terms. He’s an antique. Not only aging, but often broken down and repaired. Yet he’s still the heart of any machine. And the heart of new championship dreams in Chicago.

“There’s no way we’re declaring ourselves, the champions,” said Motta. “But I can sit on the bench night after night and feel more comfortable playing an opponent than I ever have. Getting Nate was . . . well, it’s like a guy who keeps playing par golf. You need some trick, something extra special, to get below par. We have an adequate situation at center, but I wanted more than adequacy.”

Motta wanted more than good defense and board strength from his center. He wanted scoring. Thurmond fits all these categories, plus two more. “Nate plays very well against Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Bob Lanier,” said Motta of the Milwaukee and Detroit centers.

The Lakers, Pistons, and Bulls are members of the NBA’s Midwest Division. All three made the playoffs last year. It is likely the toughest division in basketball. “I’ve felt all along our forward line, Chet Walker and Bob Love, was comparable to any set in the league,” Motta continued. “And we don’t lose games because of our guards, who get the ball up the court, play good defense. And even though we’ve gotten good defense from our centers, Nate will give us even better defense.

“But I’d never make a trade just for defense. I don’t know how many points Nate will score this year, but I do know that opposing centers will pay closer attention to him than they did our previous centers. No more forgetting the Bulls’ center and two-timing one of our forwards. Those days are gone.”

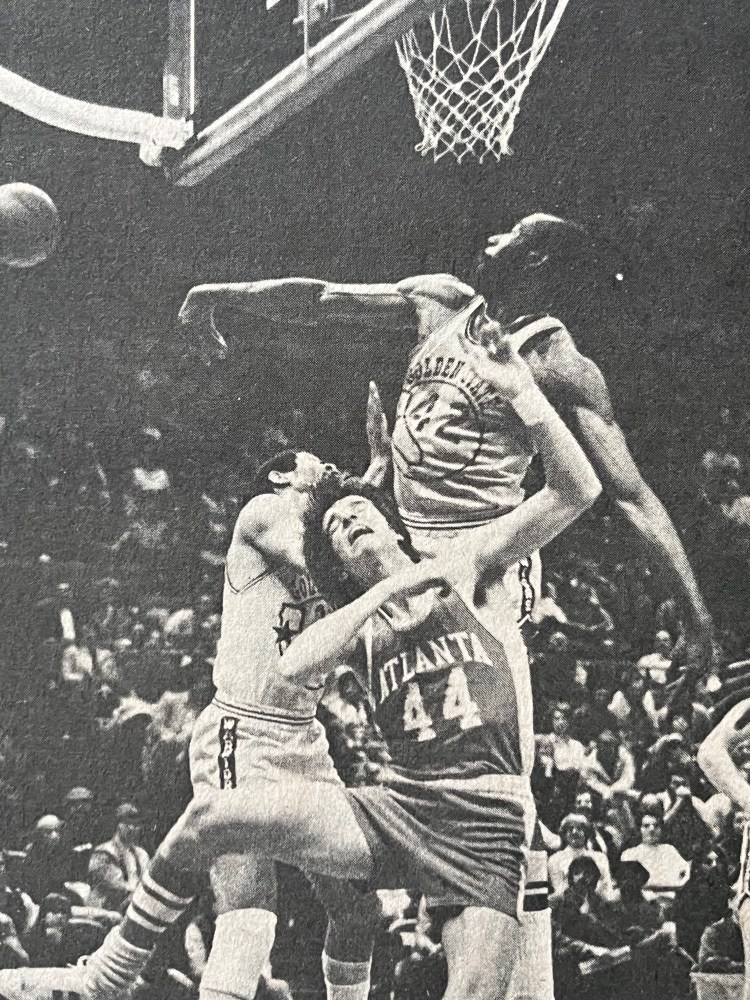

Motta gave up center Cliff Ray and reportedly $100,000, plus a draft pick, to the Golden State Warriors for the 33-year-old Thurmond. For the Warriors, Thurmond’s physical condition and his salary, which is around $240,000, meant a parting of the ways. Golden State has finished just one year in the “black”—in 1966-67, the year before Rick Barry jumped to the American Basketball Association.

A new Warrior management wanted to save some money, so they sliced off Thurmond’s salary—Ray reportedly makes $60,000 per annum—plus the $100,000 paid to the disenchanted Cazzie Russell.

Thurmond, in 10 years with the Warriors, had missed 125 some games (about a season and a half) with various injuries. He missed the final month of last season, and the Warriors collapsed. The Warriors felt a younger player (Ray is 26) would provide more dependability—and years—in the pivot. It’s all a matter of priorities.

“I know they’re counting on me, but I don’t feel any pressure,” said Thurmond of his new role with the Bulls. “I’ve maintained a good scoring average during my career. I had five 20-point-per-game seasons. I didn’t score as much last year, but I didn’t shoot as much either. I think I can get the Bulls 17-18 points a game. But over the course of the year, they might not need that much, because they play such tough defense.

“I’ve had injuries, but they haven’t slowed down my career. Motta told me when he got me that it was his lifelong dream to get a big center. That made me feel good. The Bulls always seem to win 50 games. Maybe I can help them win 60 or more.”

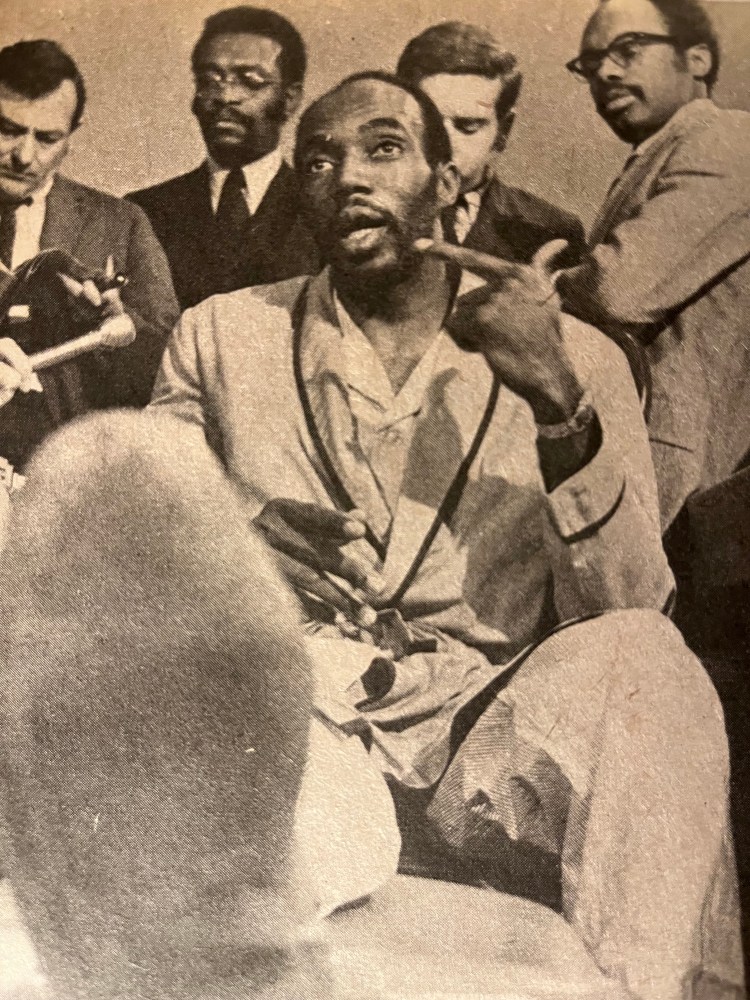

It was astonishing to Motta—and a number of Warrior fans—that Thurmond was available. “At the end of last year, I began reading and hearing rumors that Nate was expendable,” said the Bulls coach. “I called Bob Feerick (then Warrior general manager), but then talks died down. When Dick Vertlieb replaced Feerick, I got in contact with the Warriors again. It took five weeks of negotiating, some of it at my cabin at Bear Lake on the Utah-Idaho border.”

However, Motta was concerned with Nate’s physical condition. Thurmond had a severely sprained instep the final month of 1973-74. The Bulls didn’t want a one-legged center.

“We were worried enough to where there was a stipulation in the deal that Nate had to pass a physical by a doctor of our choice. We made the examination and found Nate healthy enough, so we went ahead with the trade,” Motta recalled. “No, I’m not worried about Nate’s health. I worry about the health of all my players—Chet, Sloan, Love, ALL of them.”

Thurmond, in his younger days, was a 45-48 minute-per=game center. The big man, despite his 6-11 ½, 227 pounds, seldom was rested. If the 76ers and Lakers could get a full game out of Wilt Chamberlain, why couldn’t the Warriors do the same with Thurmond?

Motta didn’t pursue Thurmond with the idea, figuratively speaking, of burying him, six feet under Chicago Stadium. He’d like to keep him three feet over the rim. “I have a regimented time schedule with Chet that will prolong his career. I want the same thing for Nate,” the coach said. “There’s no reason why the two of them can’t play 30-32 minutes a game without hurting themselves or the team.

“This may sound corny, but Nate and Chet are like natural resources . . . oil wells. You don’t want to pump them dry too soon. If I can save them, five minutes here or there, those minutes are in the bank, and I’ll collect the dividends later on.”

Which is reassuring to Thurmond, a lot more reassuring than the manner in which his relationship with the Warriors ended. That was on an icy note.

“Right after the trade was announced, Jeff Mullins called and so did Al Attles,” said Nate. “I thought it strange that Rick (Barry) didn’t call because I had called him when he went to the ABA. Not that I cared all that much, but he always said he was such a good friend. And Franklin (Mieuli) never called either. I’m usually hard to reach, but he never even left a message. Nothing.”

Mieuli, owner of the Warriors, always has played the paternalistic role. Each Warrior player is like a son to him, or so he says. But when Nate left, nary a word. It wounded Nate’s pride, but not his professional sense.

“The 10 years I was with the Warriors they paid me,” he said. “They don’t owe Nate Thurmond anything, and I don’t want them to owe me anything. It was a business deal, and they felt they were helping their business.

“I never believed that Nate Thurmond was the Golden Gate Bridge. Athletes are meat, and once you get to thinking that you aren’t, then you’re in trouble.”

However, Thurmond knew something was up when the Warriors asked him to take a physical before training camp. “The day it happened, a waitress from my restaurant called and said, ‘Oh, I feel so bad,’ and I said, ‘Oh, it happened?’

“My first reaction was for my restaurant, The Beginning, which I opened two years ago and which was doing very well . . . even though I was hardly around. I wanted it that way. I wanted people to like the food, the surroundings, without my having to be there to draw them in.”

His next reaction was to a new city, new friends, new way of doing things. “I don’t think life for me in Chicago will ever be like it was in San Francisco. I like entertainment, and it was always easy to get a ticket to some show in San Francisco. I was always around, so I knew people. I don’t think I’ll ever become as well known in Chicago,” Nate said.

Not if Motta has his way. And he usually gets his way. Even his newest “part” knows that. “Motta gets more out of his material than any other coach. He’s like the George Allen of basketball. Dick’s had some old guys and others you wouldn’t consider stars and really made them work together,” Thurmond said.

And what about the fiery Motta temper? The little bantam rooster leads the league yearly in coaches’ fines. He even topped himself in the last playoffs, when angered by an official’s call, he whipped off his jacket and threw it at the official.

“He’s like Red Auerbach in that sense,” said Thurmond. “Auerbach’s players never had to get on the ref because Red would do it for them.

“One thing Motta really hates is turnovers. His theory is possession of the ball is worth at least one point. I’d hate to lose a ball in a key situation and then have to face him.”

This is Jerry Sloan’s seventh year with Motta, and the talented guard pays his coach the ultimate compliment. “There are probably 13 or 14 teams in the NBA who’ve had better personnel than we’ve had over the past few years,” Sloan pointed out.

But that was BBT (Bulls Before Thurmond). Nate the Great adds a new dimension in Chicago. “Nate will give us scoring in the middle, a luxury we haven’t had before,” said Sloan. “And he’s a great defensive player to go along with a great defensive team. So he will even make a difference on defense.

“The ideal situation would be to get 15-16 points from five guys, which is how Motta’s offense is designed. We’re closer to that offense than ever before.”

Sloan, like his coach, is reluctant to predict a title for the Bulls. “You still have to play,” the guard stressed. “You can write all you want, but there are 82 games and whatever follows. A lot can happen. But the big thing is that everyone stays healthy.”

Another new addition on the Bulls has Motta excited. Cliff Pondexter, a 20-year-old forward, was drafted No. 1 as a hardship case and signed after just his freshman year at Long Beach State. Pondexter was the youngest player ever signed by the pros until the Utah Stars of the ABA cornered Moses Malone, who was headed for the freshman year at the University of Maryland before those Rocky Mountain Millions changed his direction.

“I don’t want to put a monkey on Cliff’s back, but he’s going to be a star in this league. He’s a genius,” Motta exclaimed. “He’s a man. You can tell he’s 20. Spencer Haywood came into pro ball just a year older, and he did all right. Cliff will take some of the rebounding load off Nate.”

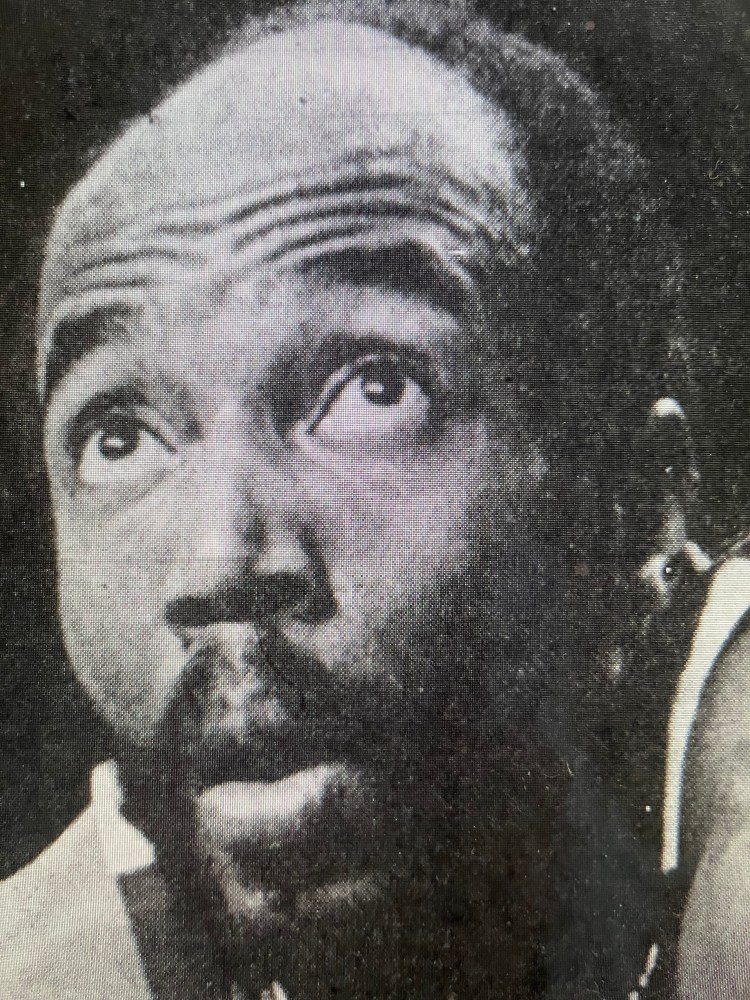

Meanwhile, Thurmond begins his “second life” in the NBA. A year ago, Thurmond stretched his long legs in the back room of The Beginning. His Rolls Royce, with the “Nate 42” license plates, was parked out in front. Soft music filtered through the restaurant, interrupted only by the basso profundo voice of Nate’s bartender serving the luncheon crowd.

“The only thing missing from all this basketball,” said Nate, scratching his beard, “is the championship. That’s the only goal I have left.”

He thought it would happen with Barry, Mullins, and the rest in Oakland, where the Warriors play their home games. But it didn’t. It may not if Golden State opponents drop off Ray to two-time Barry. Motta may have transferred this problem into Attles’ lap. [Ed note: As mentioned above, the Warriors would win the 1975 NBA championship with Ray playing quite well.]

But the championship could happen in Chicago under Motta’s leadership and Thurmond’s center play. “I’d like to finish out my contract, which is two more years and an option year,” said Thurmond. “I’m sure I wouldn’t want to go much further. That would make it 14 years. That’s enough. But if I could help, the Bulls win a championship this year, then I might consider retiring.”

Through all of this, Dick Motta pretends not to count the years he will have Thurmond. He thinks instead of the years he didn’t have Thurmond. “I’ll tell you personally how I feel about it,” said Motta. “I’ve been in this league seven years, and I deserved the right to coach Nate Thurmond.”