[The blog’s last posted story asked whether the ABA would be ready in 1970 for the arrival of the New York Nets’ fiery new “college” coach Lou Carnesecca. Now, in the post below, we get an answer. Reporter Pete Alfano spent a day trailing Carnesecca during his second season with the Nets, who nearly won the ABA title that year. Alfano’s piece offers an excellent behind-the-scenes look at life in the ABA and captures the action during a league game in the Island Garden, the Nets’ creaky home-floor before relocating to Long Island’s brand-new Nassau Coliseum. Alfano’s story ran in Newsday on December 11, 1971. Enjoy!]

He sits with his feet propped on an easy chair in the living room, barely aware of the bank robbers making their getaway in a 1954 Ford or of Cary Grant’s romancing his leading lady.

New York Nets basketball coach Lou Carnesecca probably has witnessed the endings countless times. The old movies are merely a backdrop, a source of inspiration. Some people are motivated by silence, others by soft music. Carnesecca diagrams plays for Rick Barry and his teammates while the Marines head back to Bataan.

“I love the old movies,” Carnesecca says. “I watch them over and over again.” His night life, like his daytime activities, is devoted to basketball. It’s a full-time job, and the inspiration comes at 2 P.M. or 2 A.M.

He has to be aware when it does. A new play, Carnesecca chomps even harder on his abused pencil and squirms a bit more through a restless night. A new play. Something to share with the players the next day. Will it work? Has it been used before? The nights are too long to wait. The next game isn’t soon enough.

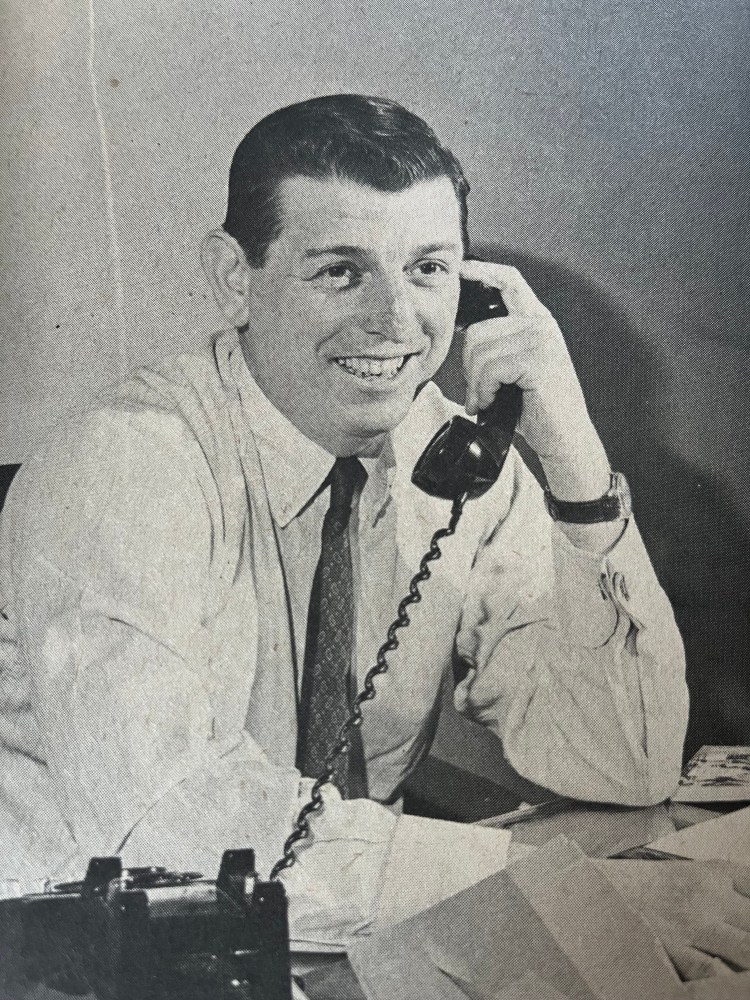

“I get to the office at 10 A.M. I answer mail and do organizational work. People come to visit, and I talk with people who have ticket requests.”

The play will have to wait. There’s a call from Jack Leaman, the basketball coach at the University of Massachusetts. “Hello, buddy, how ya doin’?” Carnesecca says. “How many do you need? What date is that?” Leaman coached Julius Erving last year, and now the college star from Long Island’s Roosevelt High School plays for the Virginia Squires. Leaman is bringing his team down to see Erving play against the Nets.

Carnesecca puts down the phone, and for a brief instant the smile disappears. Carnesecca reflects on what might have been. Julius Erving, the one that got away. Erving had two years remaining of eligibility, but decided instead that he would sign a big pro contract. He walked off the street and asked the Nets to sign him. They refused on ethical grounds, but wars, such as the merger war between the NBA and ABA, are rarely concerned with ethics. The Nets know that now.

****

“Let’s see the new uniforms,” and Carnesecca is fidgety again. “Fritz, where are the uniforms?”

Trainer Fritz Massmann walks into the office with the Nets’ mod, new uniform. White pants and jersey, with wide red and blue stripes running lengthwise down the front. There are matching flare warm-up slacks. The Nets will wear them on opening night in the Nassau Coliseum.

“How do you like them, pretty sharp, uh?” Carnesecca says and then walks briskly back to his desk.

Carnesecca looks as out of place sitting behind a desk as a banker would look on a pro basketball team’s bench. But Carnesecca has to work at the desk because he is also the Nets’ general manager. It is a full-time occupation in itself, involving signing, scouting, and trading players.

“Only in terms of player personnel, though,” Carnesecca says. “I only help in those other things, such as setting up speaking engagements.”

There are things to do, and Carnesecca excuses himself for a moment. He takes out a pad, grabs a pen—as if he were snaring a pass from one of his players—and begins writing. He frowns as he writes. Carnesecca approaches the letter-writing chore with as much enthusiasm as a child about to swallow a spoonful of castor oil.

“I write them longhand,” as he looks up to ask the spelling of a word. “The secretaries usually have trouble deciphering the content. They come back a lot, asking me what I wrote. I have one of those talkie things to dictate into, but I always get it screwed up. There is tape all over the place—a real Peter Sellers bit.”

Carnesecca leans back, the letter-writing chore is over. Time-out for reminiscences. “My father was a typical Italian father,” Carnesecca says. “He wanted me to become a doctor and play the accordion. I guess he thought I would play at the feasts. I took up the clarinet instead, and through my whole life, I haven’t learned to play either.”

****

Carnesecca has come a long way from his home on East 62nd Street in Manhattan. “Between First and Second Avenue,” he says. “The Block, we called it. My wife, Mary, lived across the street from me.” The neighborhood was mostly Italian, and Italians were expected to marry Italians. And to learn to play the accordion. Basketball was a game, and few could expect to earn a living playing a game. Or coaching a team.

“What time is it?” and Carnesecca is looking at his watch. “I’m getting edgy,” as the fidgeting becomes more noticeable. “I’m going over there [to the Nets’ homecourt, called the Island Garden] at 4:30. I’ll talk to John [Kresse, his young assistant coach and scout] and maybe we’ll look at some films.”

The Nets are the film attraction, not James Cagney, and Carnesecca pays close attention, hoping to spot flaws of his own players that he can correct. He’ll take a look at his opponent, too, looking for weaknesses. There isn’t much time.

The most difficult part of Carnesecca’s day is the waiting. The tightening in the pit of his stomach is something he lives with most of the season, and the tension is even greater before one of the 84 regular-season ABA games.

“It used to be that after a victory or defeat at St. John’s, I could sleep,” Carnesecca says. “Now, I wake up earlier in the morning. That’s one change I’ve noticed.”

“He does?” Kresse is surprised about a new fact of Carnesecca’s life. It is one hour before a Friday game with the Floridians, and Kresse is watching some players take extra shooting practice.

“Yeah, sometimes I take walks behind the Island Garden,” Carnesecca says. “I feel like a monk. I think of all the things that can go wrong.”

Now Carnesecca is in the locker room, diagramming plays on a blackboard. Perhaps the play he was thinking about the night before. Outside, Kresse peers from behind a pair of yellow-tinted glasses as John Roche and Bill Paultz continue to practice.

“Kresse handles me well,” Carnesecca says. “He’s been with me eight or nine years and knows what I want. Any suggestions he makes, I take.”

People file into the Island Garden, which was enlarged this year to hold 6,000 people. It still resembles a big barn, where the fans are so close to the players they can seemingly reach out and touch their favorites and where cotton candy is a big seller. The intimacy and carnival atmosphere will disappear when the Nets move into the Coliseum, but Carnesecca’s and the Nets’ close identity with the fans will remain, they hope.

“You have to make a fan feel like he’s your guy,” Carnesecca theorizes. “He pays the bill.”

The bill-payers cheer as the Nets come on the court. “Hey, Rick,” a fan shouts, waving a pen and paper at Barry. Neither he, nor his teammates, pay attention, however, as they run through the warm-ups they’ve practiced infinite times.

“Stuff it, Ollie, stuff it,” but Ollie Taylor, the Nets’ high-jumping guard, settles for a layup. Near the bench, Carnesecca waves hellos to the crowd.

While Barry, Bill Melchionni, and the rest of the starting five are introduced, Carnesecca sits uneasily on the bench, occasionally applauding with the fans as the players run onto the court. It’s as close as he comes to cheerleading. Pep talks are for Pat O’Brien and the late show.

“Okay, let’s go,” Carnesecca gives some last-minute instructions, and his players take the court for the game—what Carnesecca has been waiting for. Starting at St. Ann’s High School in Manhattan, then coaching under Joe Lapchick at St. John’s, before taking over there himself, Carnesecca has worked 21 years to earn a seat on a pro bench.

He doesn’t stay seated long.

“C’mon, let’s move,” and Carnesecca is up, imploring his players to move more on offense. The Floridians take an early lead, and Carnesecca is down on one knee, alternately praying and working up a locker-room sweat. He is a most demonstrative coach, expending as much energy as his players.

“I fear for the guy who isn’t demonstrative,” he says. “The acid takes its toll.”

On Carnesecca, too. While Kresse sits stoically, eyes glued to the court, Carnesecca jumps and heads for the other end of the bench. “Atta boy, Joe, atta boy.”

Joe DePre, who played for Carnesecca at St. John’s, has just made a jump shot, and the Nets are two points closer. In another game, a basket by DePre prompted Carnesecca to run onto the court and pat the guard on the back while play continued. “Did I do that?” Carnesecca asks. “I didn’t even know it.”

While he was at St. John’s, one of his players stole a pass and went uncontested down the court for a layup. Carnesecca matched him stride for stride along the sideline. “Pass it to Louie, he’s open,” a voice in the crowd shouted.

The fans could joke then. In five years as head coach at St. John’s, Carnesecca’s record was 104-35. Last season, his first as a coach of the Nets, the team lost 44 of 84 games.

“No, no,” Carnesecca leaps out of his crouch and signals the letter T with his hands for a timeout to slow down the Floridians’ momentum. The players sit for a breather while Carnesecca, on one knee, faces them, constantly gesturing with his hands.

“Communication is the important thing,” Carnesecca says. “You have to understand the personality of a pro. They have achieved success with their individual skills, and why should they change just because you tell them to? They will change, though, if the players know you can make a contribution to him or the team.”

****

Carnesecca’s contribution made during the timeout, the players walk back on the court. He has a last word with Barry, his superstar, and for the first time since the game started, Carnesecca sits down. Roche passes the ball inbounds to Melchionni, and Carnesecca is up again. “Okay, let’s go,” there are no time-outs for the coach.

“I have to try and group all my individual forces and energy in every game,” Carnesecca says. “A lot of people have been telling me for 15 years to take it easy. I am physically drained after each game. It takes its toll.”

An already-weary Carnesecca trudges off to the locker room at halftime. The Nets have tied the Floridians, but the team hasn’t played well, and it shows on the coach’s face. While Carnesecca is diagramming new strategy on the blackboard, the fans are talking about the 45-foot shot Melchionni made that tied the score.

“It’s a matter of concentration,” Carnesecca says. “The [team’s] problems are solved on the floor. They won’t come down from heaven.”

It’s evident that the Nets could use a little supernatural help as the second half begins. They fall behind again. The halftime chalk was wasted. Carnesecca shadows players in and out between verbal outbursts against the referees and instructions to the players. He can be heard more easily as the hushed crowd watches the Floridians increase their lead from five to 10 to 15 points.

“I think the players are getting used to me,” Carnesecca says. “When I yell out there, some interpret it as my disagreeing with their play. But my displeasure was with the play itself, not the player. He has to know I’m his guy, and I have feelings for him.”

Almost unnoticed, Carnesecca slips back into his chair. There is still most of the fourth quarter to play, but for Carnesecca sitting down is conceding defeat. He wipes his forehead with a white handkerchief and talks quietly with Kresse. Defeats come more often in the pros, and even Carnesecca must learn to conserve himself. In college coaching, where there are considerably less games, it was different.

“We were playing Army once while I was at St. John’s, and it was like hand-to-hand combat,” Carnesecca says. “On one play I found myself down under the basket, sitting in a seat next to a woman and a little kid. I was giving her the elbow. The referee came over to me and said, ‘Lou what are you doing here?’ I was very embarrassed.”

He was embarrassed now, too, watching his team being soundly beaten. “Timeout, timeout, Johnny,” and Carnesecca is up again. The Nets are well out of it, but Carnesecca is paid $40,000 a year to coach 48 minutes each game, and something on the court was upsetting him. The players head slowly back on the court, and Carnesecca prepares to sit down looking back first to make sure the chair is still there. “I once fell off my chair, and another time I sat and the chair wasn’t there.”

****

The torture is finally over; the Floridians have humbled the Nets. Carnesecca walks slowly to the locker room, accepting condolences along the way. He looks older than 46, and it’s difficult on October 29 to accept the fact that he will endure 75 more games in the regular season.

“I don’t go to the games because I feel he is going to have a heart attack,” says Mary Carnesecca. “I just turn on the radio every half hour for the score.”

The door to the locker room remains closed after the game for a few minutes as Carnesecca talks to the players. It opens, and reporters head inside. Carnesecca has loosened his tie and removed his sport jacket. A Coke can dangles in his right hand.

“Erase that,” and the blackboard diagrams are gone. And now Carnesecca must talk about the loss. Some coaches are evasive during interviews, others belligerent unless they win. Carnesecca is eager to share his frustrations, although much of what he says is colorless to someone who has seen him on the bench.

“We just weren’t ready. I don’t know why,” Carnesecca says. He searches for a reason for the lack of preparation. “The greatest fear is failure, and it is also the greatest driving force,” Carnesecca says. “You lose more here [in the pros], but you have to look at the overall picture. You must learn to live with defeat. The games are so frequent.”

At St. John’s, Carnesecca was forced to live with a defeat for several days, sometimes for a week. The Nets have an opportunity to redeem themselves two nights later. “That’s good when you lose,” Carnesecca says. “I can hardly wait for the next game. When we win, I don’t want to play for an eternity.”

The locker room empties, and Carnesecca repeats the answers for a late-arriving reporter. Kresse speaks to some friends, while Massmann is the busiest, collecting sweaty uniforms. Outside, 50 or so fans linger asking for players’ autographs.

Carnesecca is the last to leave, and the drive to his home in [the Queens’ neighborhood of] Jamaica will be a long one. He pauses to chat with some fans, answering their questions as he would those of a reporter. His coaching may be criticized and the transition from college coaching has been slow, but it’s been smooth in one respect. Carnesecca always has been a pro at public relations. “I’m conscious of public relations. I try to sell basketball.”

The drive home is mechanical. The lost game is on Carnesecca’s mind. He also thinks of his wife and daughter, Enis, a freshman in college, and their reactions to the game. “All I know is when I go home, Mary says, ‘Take out the garbage.’”

His wife and daughter try to ignore the loss, pretend it never happened. “I try not to talk about the games too much,” Mary says. “I let him lead the way. I know him so well. I try not to be psychological.”

The car pulls into the driveway, and the inner tension reaches a peak. Defeat is too fresh in Carnesecca’s mind for it not to show on his face. “I consider my family, but I guess I become selfish. The family lives with wins and losses. I think to myself, ‘Please don’t take the game home. Don’t let it affect your family.’ But I show depression and dejection. I don’t think you can call it anger, though.”

Eventually, Carnesecca relaxes, although sleep is a long way off. While the fans at the Island Garden think about weekend plans, Carnesecca replays the game again and again. How much longer is he willing to endure the life of a basketball coach?

“I can’t picture him doing anything but coaching,” Mary says. “But I do hope he will retire from coaching and still be young enough to enjoy life.”

“I’ve been coaching for 21 years and wouldn’t know what else to do,” Carnesecca says. “I have wondered how it would feel to go to a game and not be a part of it. I do hope I have enough brains to know when to say this is it.”

It’s late, and there’s a full day of work awaiting Carnesecca tomorrow. Mary has gone to sleep, and Lou is alone. Still restless and as fidgety as he was 17 hours earlier, he switches on the television.

Carnesecca finds his favorite chair, kicks off his shoes and watches an old movie. With a pencil and pad, of course. “Hmmmmm, wonder if this will work,” and the countdown for the next game begins.

Still a great describing the Life of Louie 54 years later.

LikeLike