[A quick admission. I’m a dyed-in-the-wool Utah Jazz fan, going back to the early 1980s and the franchise’s first winning team in Salt Lake City featuring Adrian Dantley, Darrell Griffith, Mark Eaton, and Rickey Green. Calling the action on the radio was the folksy, always-fun Hot Rod Hundley, who’d learned his play-by-play chops in Los Angeles working alongside the great Chick Hearn. Hundley’s signature lines in Utah were: “You gotta love it, baby,” when the action turned wild and wooly, and “You can put this one in the refrigerator,” when the Jazz secured another hard-fought victory.

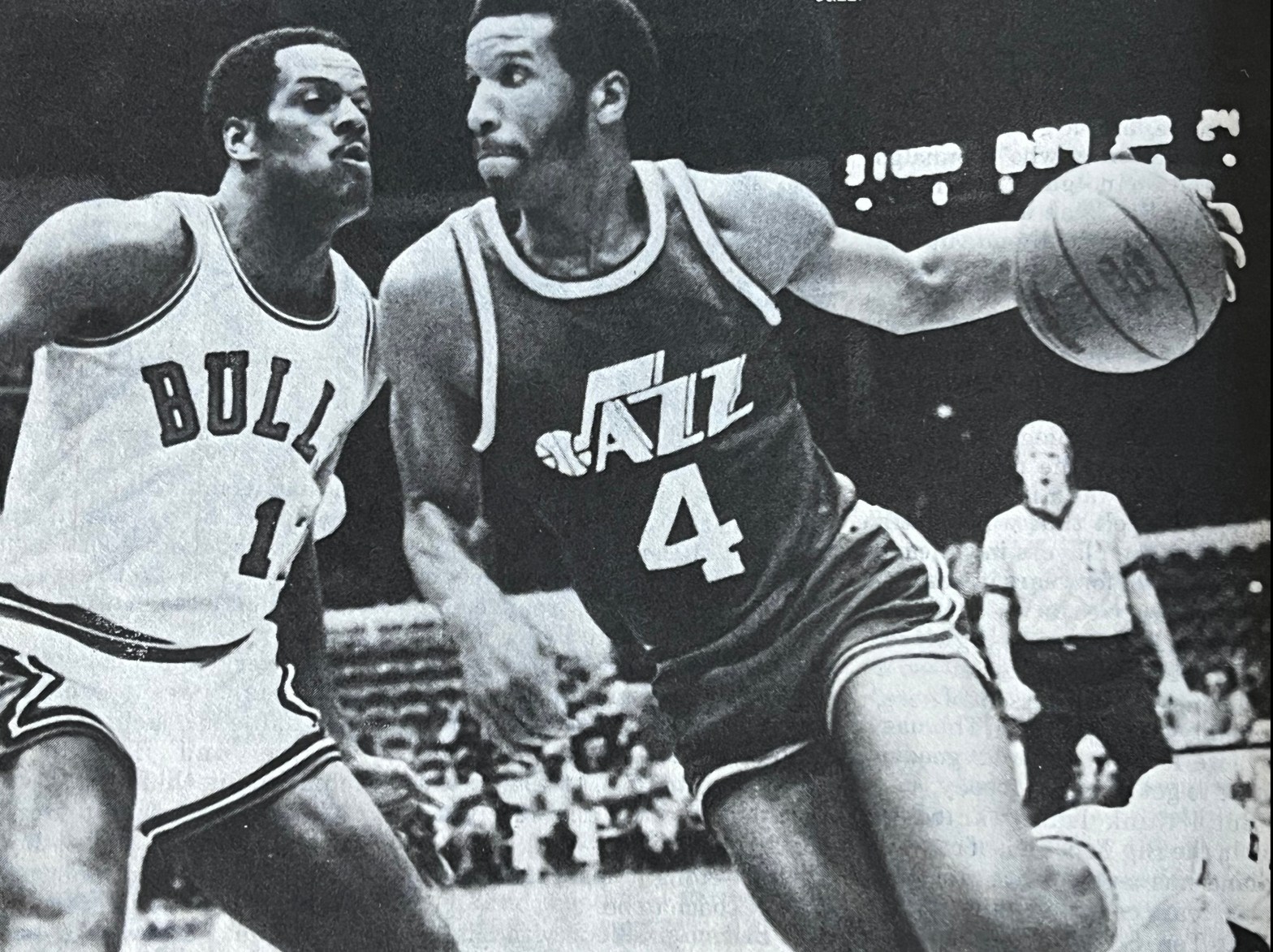

In his autobiography titled, Hundley recalled relocating with the former New Orleans Jazz to Salt Lake and trying to sell pro hoops in those first seasons with three big-time NBA scorers on the roster: Pete Maravich, Bernard King, and Adrian Dantley. Hundley wrote: “In Dantley, Maravich, and King, we had three guys who combined for more than 58,000 points in their career. That’s more than Karl Malone, John Stockton, and Jeff Hornacek combined for, but there was no comparison. King only played 19 games for the Jazz, and Maravich only played 17 games in Utah. Dantley was the only one who emerged as a key player for the Jazz in their early years in Utah.”

In this article, published in the Winter 1980-81 issue of the magazine Basketball Special, sportswriter Jay Searcy taps out a short piece about the early-and-improved Utah Jazz. Searcy presumed that the Jazz would harmonize in 1981 around Dantley, King, and college superstar Darrell Griffith, the team’s top draft pick. Searcy was wrong about King. He was battling his demons while in Salt Lake, got into some serious trouble, and was suspended for most of the 1979-80 season. By September 1980, or weeks after Searcy had filed his story, the Jazz sent King to Golden State for his sake and to clean up the team’s image.

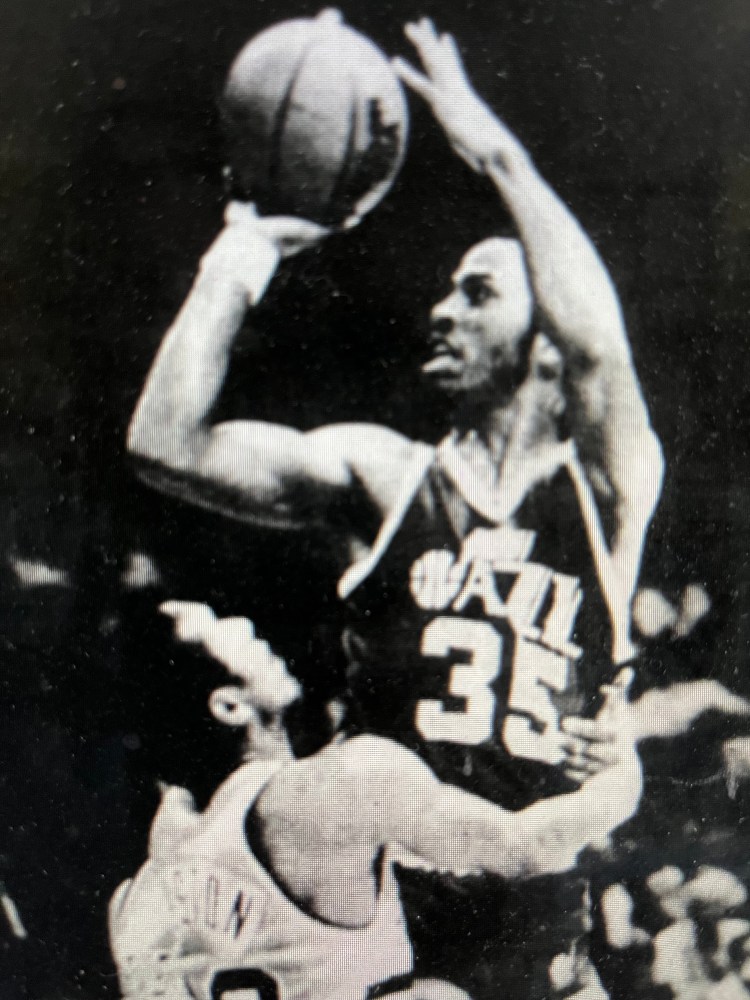

Searcy was right, though, about Dantley and Griffith. They would put on quite a show for several seasons in the old Salt Palace, solidifying the franchise in Utah and shoring up its fanbase across the Wasatch Front.

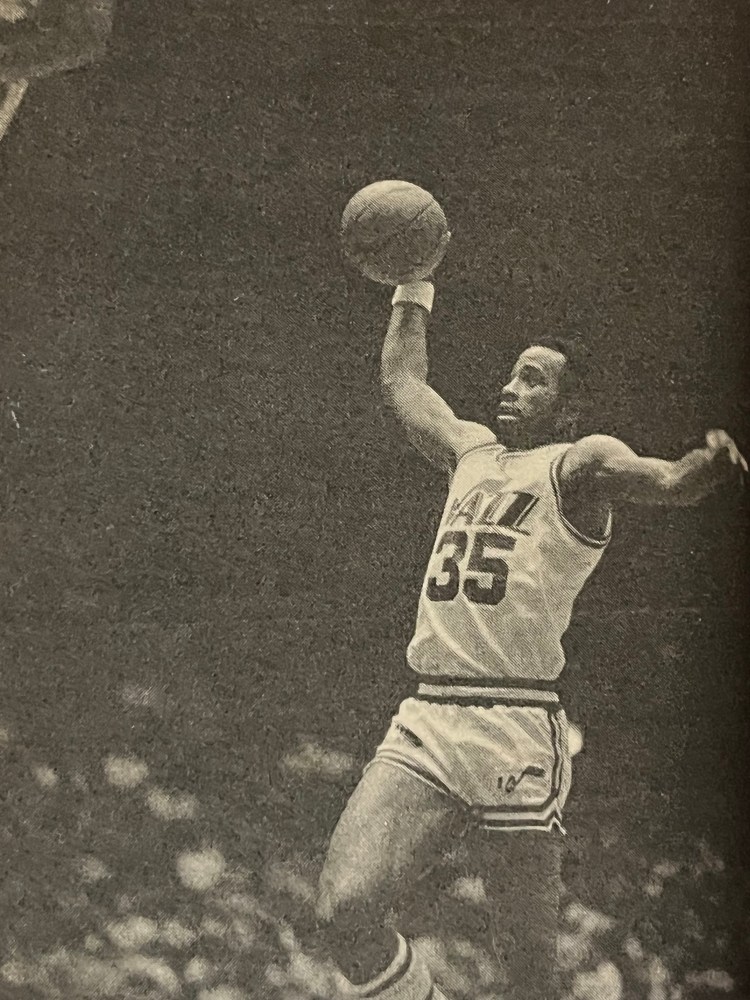

Hundley would later lament one small might-have-been. Instead of drafting Griffith first in 1980, the Jazz could have grabbed instead forward and future Hall-of-Famer, Kevin McHale. As Hundley correctly noted, McHale turned out to be a franchise player, Griffith not quite. “The Golden Griff,” as Hundley called him, could didn’t have the best of hands and could fumble-finger passes and open shot attempts. Funny that those same hands releases one of the softest, high-arching, and accurate shots from three-point land during the 1980s. Or, as one publication put it, Griffith had a “hit-the-ceiling three-pointer” that was beautiful to watch.

Left unsaid, Griffith was a class act in Utah, and the franchise was lucky to have him for 10 seasons that produced a solid career average of 16.2 points per game. And Hundley would have been the first to agree.]

****

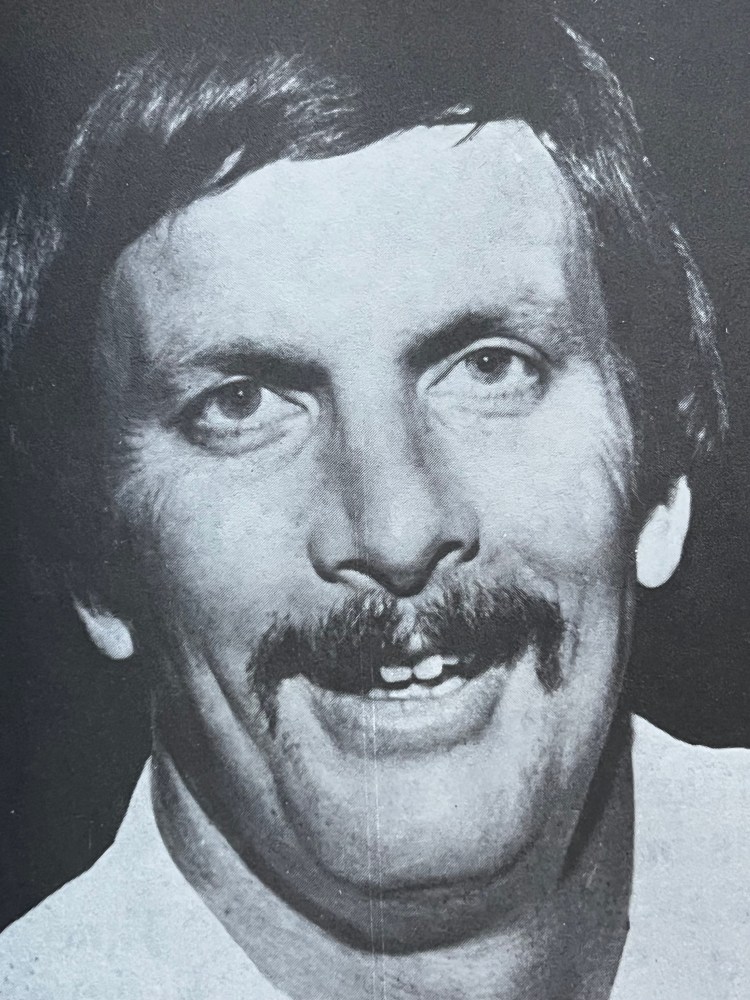

Tom Nissalke, coach of the Utah Jazz, would like to tell you this is the year that the Jazz win the NBA championship. He would like to . . . but he can’t. Not even with the addition of Darrell Griffith, the hottest item in college basketball last season. Not even with Adrian Dantley, Bernard King, and Darrell Griffith on the floor at the same time. No, the Jazz, which turn six years old this season, isn’t quite ready.

Sadly, this team is still paying for mistakes made by well-meaning owners and management when the team was in New Orleans. There, they were impatient and tried to trade draft choices for an instant winner. It was a mistake that will not be repeated by the new owners of the Jazz, nor by coach Tom Nissalke, who recently signed a new multiyear contract.

“I don’t think there are any shortcuts in this business, unless you have unbelievable wealth,” said Nissalke. “Los Angeles possibly could buy a championship. New York (Knicks) has tried spreading money around fairly liberally, and they haven’t been able to (succeed). It’s unfortunate for us now. It was just that they (former Jazz management) were not thinking through completely some of the trade decisions in the past.”

Nissalke pauses as if he is dreading what he is about to say. “They traded three first-round draft picks for Maravich. They traded two first-round picks for Gail Goodrich. Between Maravich and Goodrich, that’s five first-round picks. Another one was a No. 1 pick traded away to get guards. Fortunately, Houston was good enough to take Slick Watts from us, so now we have a No. 1 choice next season.”

The Jazz’ No. 1 pick a year ago went to Los Angeles. “That should have been our pick,” said Nissalke, “and it was Magic Johnson.”

Magic Johnson, of course, helped turn Los Angeles into a world championship team last season. Larry Bird, another rookie, helped make the Boston Celtics a serious contenders again. Could not Darrell Griffith, the guard who led Louisville to the NCAA title, do the same for the Jazz in 1980-81? Especially with Dantley?

“No,” says Nissalke. “It takes more players than that. But those two players, along with our others, can make us respectable this season. We’re still two years away, I’d say.

“We have Bernard King back, and if he comes back in the right frame of mind and is ready to play the way he played when he was with the Nets, he could make a big difference. He played in the California summer league and was clearly the top player out there. That doesn’t mean much, but it does mean he was in good physical condition.”

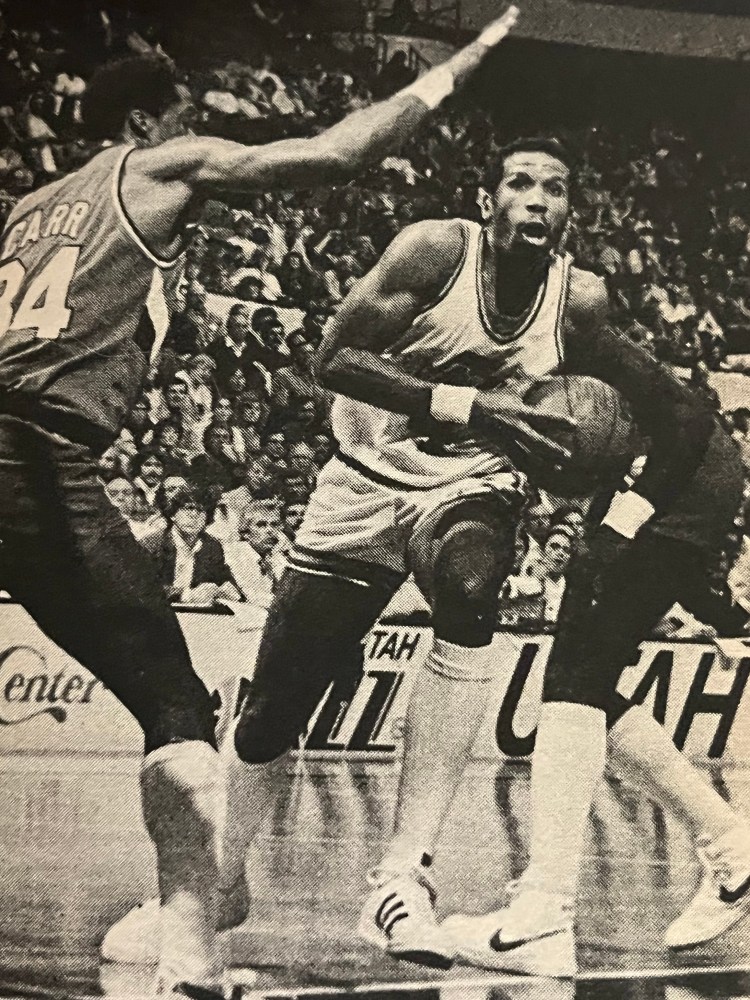

The trouble with the Jazz this season is that the team simply is too small. Ben Poquette, the probable starting center, stands 6-9. The fourth-year pro was the leading rebounder last season, averaging only seven a game.

The Jazz were one of the top shooting teams in the NBA, yet finished last in its division with a season record of 24-58. The big reason? The team was dead last in the league in rebounds, both offensive and defensive. This year’s team will be better, but not much bigger. Dantley, 6-5, and King, 6-7, will be the forwards. Griffith, 6-5, and rookie John Duren, 6-3, will be the guards.

“In the past, we’ve had weaknesses all over,” said Nissalke, “especially in the backcourt. But I think with Duren and Griffith, we now have two guards who will be our players of the future. I think our guard position is now solidified and stable. The forwards, Dantley and King, are both great players, but the big disadvantage is that they don’t have the size that we need up front.”

Despite the size factor, despite the fact that the Jazz have never had a winning record in five years, they are welcomed in Salt Lake City, their now year-old home, as if they were on the verge of a world title. And perhaps they aren’t that far away. Last season, the team, averaged 8,000 fans at the Salt Palace. “If we had that team in another city,” said Nissalke, “I think we’d be looking at 2,500 a game.”

The basketball atmosphere in Salt Lake City is good. It is the only major-league team in town, and it is surrounded by good college basketball to whet the city’s appetite for the pros. And now, stepping onto the scene, is college basketball’s most-exciting player of the 1979-80 season, Darrell Griffith.

Last year, the Jazz could find only four other NBA teams willing to play exhibition games. The Jazz simply didn’t have a gate appeal. With Griffith, the Jazz got six exhibition games quickly, and the season-ticket sales approached the 5,000 mark as fall practice began.

Griffith may not mean an immediate championship, but there is something about his presence that gives the Jazz fans hope. For one thing, Griffith has a habit of playing for winners. “Every institution I’ve ever been at, we won the championship,” he said. “We did it at Virginia Elementary, at DuVall Junior High. We won the state championship at Male High.”

And in his senior year at the University of Louisville, the Cardinals won the NCAA title. People in Salt Lake City, think the Jazz are next in line for a Darrell Griffith-led championship. “There is no more dominant player in the United States or one who means more to his team than Darrell,” said Denny Crum, the Louisville coach. “He dominates a game as probably no guard ever did.”

There has always been something special about Griffith, even when he was a little boy. The first time he ever dunked a basketball, he was in the eighth grade. He took aim at a hoop attached to his garage in the back of his house on Louisville’s West Side. He needed a push off the garage wall to do it, but he did it. “I decided that day that Darrell might be special,” said his brother Michael, “that he might be able to do things other people couldn’t do.”

“I always knew he was going to be a star,” said Darrell’s father, Monroe, a 61-year-old steel worker. “When he was a boy, I couldn’t buy enough steel hoops for him. He was always dunking and hanging on the rims and breaking them down.”

Griffith was a star on every team that he joined, but he didn’t really become a complete player until last season with Louisville. Coach Crum helped him achieve that goal, helping him understand the values of remaining in college instead of applying for hardship entry into the NBA.

“I always thought he was better off waiting,” Crum said. “Before (his senior) year, I didn’t think his game was refined enough to make it in the pros.”

Griffith worked overtime to refine his skills. Throughout the summer before his senior year, he drilled himself on his ballhandling skills, refining his passing, shooting jump shot after jump shot, sometimes right up until midnight. He did it again this summer in preparation for his first pro season.

One of the things that motivated him was that he wanted a perfect ending to an extraordinary career in Louisville. And, of course, he got it. In the NCAA final against UCLA, he took charge when the Bruins opened a 50-45 lead with 6:30 remaining. In four minutes, he was responsible for 11 points, including a silken jump shot from the top of the circle that gave Louisville a 56-54 lead and the eventual 59-54 victory.

Now, as he enters the NBA, he has new goals, new pressures. Coach Nissalke, who has been named coach of the year in both the NBA and the old ABA and who has coached in the pros for 12 years, also has new goals and new pressures.

Asked just before the season to compare this year’s challenge to all of his other challenges in the pros, Nissalke said: “I think this is going to be a little tougher. Number one, when I came here we had no surplus of players, so even if you wanted to trade somebody, no one was interested in our players. Now, at least people can say there’s an interest in a Dantley, in a Griffith, in a King. So at least we have players that people have an interest in. But we have no intention of trading.

“Our owners are cognizant that there have been just a ton of mistakes made in the past. It will take time to undo. They like where we are playing now, we are getting the kind of cooperation it takes to build a winner,” said Nissalke.

“You know,” he said, “I was talking to Doug Moe not too long ago, and he’s been with several teams also. We were talking about the importance of ownership, the importance of their cooperation, and he said, ‘I think having the right ownership is almost like having the right seven-footer.’ I think that makes a lot of sense. I think we’re making a lot of sense in Salt Lake City now.”