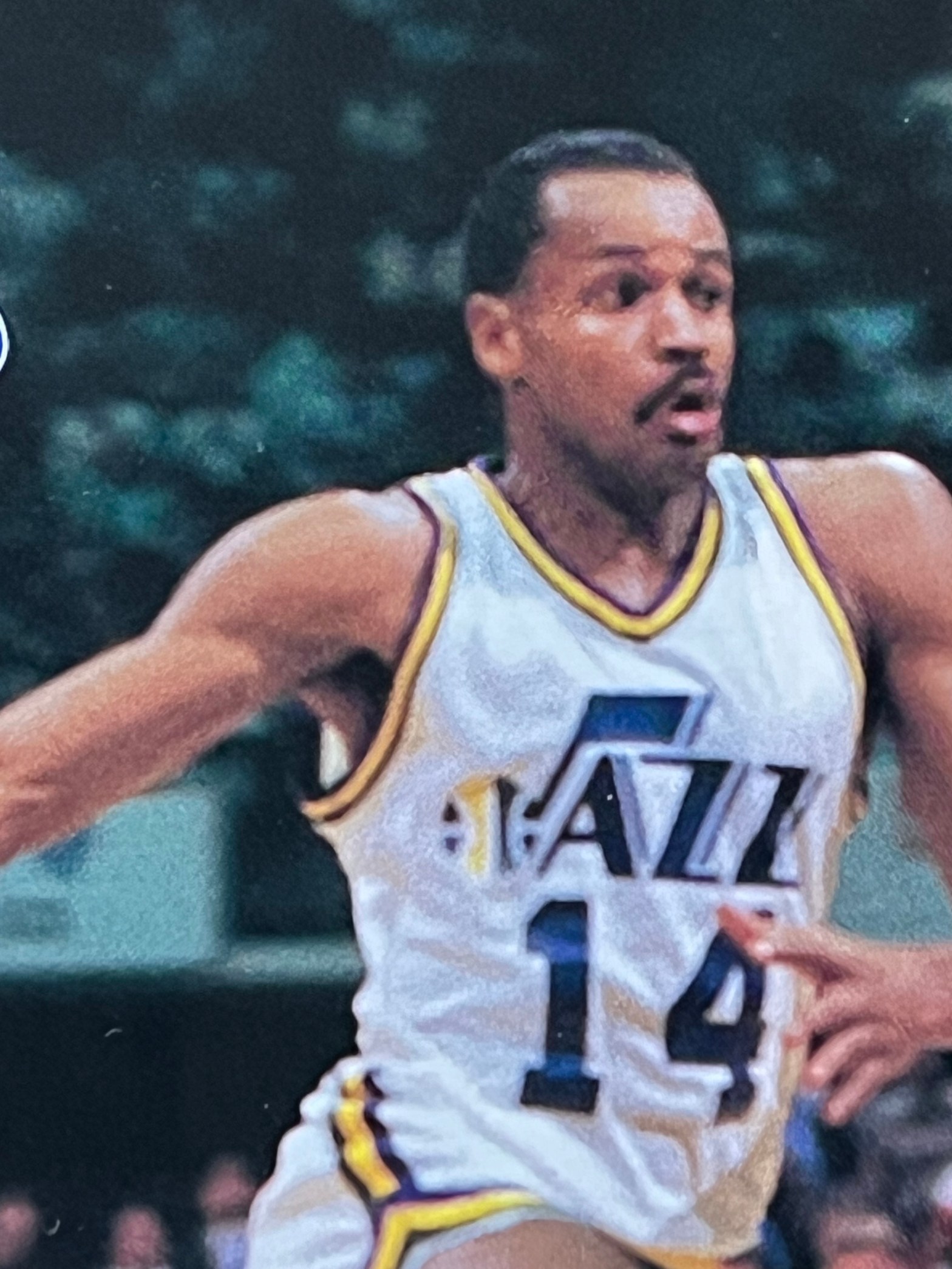

[If you listened to Utah Jazz games on the radio in the early 1980s, chances are good that you remember announcer Hot Rod Hundley repeating at least three or four times per contest, “Pass stolen by Rickey Green. They’ll never catch him.” Yes, Green could fly up the court. In fact, Hundley referred to number 14 as “the Fastest of Them All.”

Today, Green is remembered as one of the Jazz’s all-time greats. He was the guy who ran the Utah offense before John Stockton took over. But Green’s rise to NBA stardom nearly went bust first. Here’s a good summary of Green’s NBA ups and downs, as reported with no byline in the November 1995 issue of Home Court Magazine. After the summary, I’ve added a longer newspaper article from 1980 about Green’s early struggles to stick with an NBA team.]

****

“Adrian Dantley was the most important part of the beginning of Utah’s success, but getting Rickey Green was the turning point for the Jazz franchise,” says Jazz president Frank Layden. “He immediately gave us quickness on defense, and he could bring the ball up the court against anyone under pressure. He was the fastest player up the court in the league.”

Most basketball fans are familiar with Dantley’s celebrated career, beginning as a two-time college All-American, gold medalist in the 1976 Summer Olympics, and his all-pro NBA career. But very few fans are aware of the obscure path that Rickey Green took from being named first team All-American at Michigan to becoming an NBA first-round disappointment, eventually ending up in the Continental Basketball Association and working his way back to become an NBA all-star.

****

Rickey Green was drafted by the Golden State Warriors in the first round of the 1977 draft (the 16th player chosen overall), and saw action in 76 games for them during the 1977-78 season. Then his roller-coaster ride began: He was traded to Detroit prior to the start of the 1978-79 training camp and played in 27 games for the Pistons before being waived. He spent the next season playing in the CBA, averaging 23.3 points per game and 7.8 assists in 44 games for Hawaii. He was then signed as a free agent by the Chicago Bulls in the summer of 1980, but was once again waived, this time during training camp. He started the 1980-81 season with Billings of the CBA, playing in five games and averaging 22.6 ppg before getting the call from Frank Layden of the Utah Jazz.

“I remember going to Billings to toss up the opening tip-off of the 1981 CBA season,” recalls Layden. “As I’m watching the game, I’m saying to myself, ‘These kids (Green and another soon-to-be Jazzman, Jeff Wilkins) are better than anyone we have on the Jazz.’ I just kept thinking that I couldn’t believe these guys weren’t in the NBA. I went back to Billings the next night and watched them play again. Following the game, I gave Rickey a ride back to the hotel, and I remember him saying to me, ‘Don’t forget to bring me up to the NBA.’ Two days later, both Rickey and Jeff were in the starting lineup for the Jazz.”

Green finished the 1980-81 season with Utah averaging 9.0 ppg and 5.0 assists in 47 games. “The Fastest of Them All” (as nicknamed by Jazz announcer Hot Rod Hundley), had blossomed into one of the top point guards in the NBA. In 1981-82, he averaged a career high 14.8 ppg and dished out 7.8 assists per game. He continued his steady play in 1982-83 when he averaged 14.3 points and 8.9 assists per game and was rewarded for his outstanding play in the 1983-84 when he was selected to take part in the NBA All-Star Game. That season, he finished with a 13.2 ppg average, won the league steals title (averaging 2.65 a game), and established a Jazz franchise record with 748 assists (a 9.2 average) to finish sixth in the league in that category.

All told, in eight seasons with Utah, Green played in 606 games, averaging 11.4 points, 6.9 assists, and 1.8 steals per game. He remains second on the Jazz all-time list in assists (4,159), third in steals (1,100), sixth in games played, seventh in points (6,917), and ranks in the top 10 in nine different statistical categories.

With the emergence of John Stockton, Green was left unprotected in the 1988 expansion draft and was selected by Charlotte. He began the 1988-89 season with the Hornets, but was waived on February 22, 1989, and picked up by Milwaukee. The following season, 1989-90, he signed with Indiana and played in 69 games for the Pacers, then spent the entire 1990-91 season with Philadelphia, averaging 10 points in 79 games. In 1991-92, he joined the Boston Celtics, seeing action in 29 games before being waived on March 23, 1992, thus seeing his 14-year career come to an end.

After his playing days, Rickey returned to his hometown in the Chicago area with his wife, Dayna, and their now 12-year-old daughter, Candice . . . At 41, Rickey still plays ball occasionally in the Chicago area (mostly in pickup games) with an occasional tournament on his schedule. When I asked if he thinks he could still play in the NBA, Green replied: “I still weigh the same as when I played in the league, and I try to jog three or four times a week to stay in shape. I think I could still give you about five minutes a game—but I don’t think I could go to 10.”

[As mentioned above, here’s more detail on Green’s early NBA struggles. This story ran in the Chicago Tribune on June 27, 1980 under the headline, “Fallen Star,” referring to Green. But writer Skip Myslenski included some really good background on summer league ball in Chicago and some of the other players on the scene back then. Well worth the read, as is this article posted previously on From Way Downtown that mentions Green’s plight in the Continental Basketball League.]

The moments recall days of glory past. Here is Rickey Green collecting a rebound and whirling and high-stepping up the court. Confronting two defenders, jerking his head to the left, throwing his hips to the right, freezing the opponents, knifing by them, and finally flashing a behind-the-back pass. There is Rickey Green, this time on the right wing and flying, and he accepts the pass off a fastbreak, dribbles once, skies, and rattles in a jumper.

Once more it is Rickey Green, at the top of the key now and facing off against a lone defender, and he backs the man off with a juke to the left, dribbles three steps to the right, twitches his head and shoulders, watches the defender rise. He rises as his foe descends and finally tosses in another jumper just before half’s end. “Aaahhhhh!” the crowd exults.

The plays are like photographs from an old family album, so many pages of a scrapbook that remind us of times gone by. There was 1973, when Green led Hirsch High School to the Illinois championship. There were 1974 and 1975, when Rickey Green broke Bob McAdoo’s scoring records at Vincennes Junior College. There was 1976, when Rickey Green guided Michigan into the NCAA final against Indiana. There was 1977, when Rickey Green was the No. 1 draft choice of the Golden State Warriors and a starting guard at the beginning of the NBA season.

But then he started coming undone, and now the pages of that same scrapbook also hold snapshots of times less kind. There was the winter of 1977-78, when Green was benched by the Warriors and left to flounder. There was the fall of 1978, when he was traded to the Detroit Pistons and remanded to limbo. There was the season of 1979-80, when Rickey Green toiled in high school gyms for the Hawaii Volcanoes of the Continental League, and there is now the summer of 1980, when Rickey Green moves through the 25th year of his life attempting to recapture the special magic he once owned.

****

On this night, he is searching for it in the packed gym at Chicago State University, where he is leading the Chicago Defender team in the summer league sponsored by the Chicagoland Sports Federation. Once again he is on a court faced off against the best. Once again, he is on a court exhibiting his skills. Once again, he is on a court nurturing a dream.

“I know I’ll be playing somewhere this year,” he explained earlier this day. “When I can’t play anymore, then I’ll get a job. I don’t know what it will be, but then it’ll be that job first, basketball second. I know some people who just play, play, but I can’t see myself doing that. I see some guys who keep thinking they’re going to get a shot, I see that and say to myself, ‘Not me. No way.’ You want to play (in the NBA), but if it’s not there”—and here he stared off into space and unconsciously gnawed on his fingers—“if it’s not there, well, I don’t trip on it like I did. I’d like to go back. If I don’t, I’m not going to worry about it.

“But when you can still run like you did in college, when you know the game better than you did in college, it’s hard to give it up, especially when they pay you. Survive? No question I’ll survive. A lot of players bug out, but I’m young, I’ve got plenty of time to decide what to do after I’m finished. But I know I can play four, five more years, and right now it’s my way of eating, buying clothes, paying the bills. I’m not going to do it ‘til it’s not there for me anymore.”

****

At the edge of the stands, Artis Gilmore looms stoically, patiently signing the sheets of paper shoved up toward his face. Along the far baseline, Walt Frazier stands in understated splendor and tactfully rebuffs the enticements of any number of sweet young things. At the door, security guards guide people toward empty seats, and in the stands, some 2,000 basketball aficionados alternately fuss, cheer, chatter, and stomp.

It is the opening night of the Chicago State tournament, a new baby that this summer is offering treats in addition to those provided by the league that is again performing at Malcolm X College. For an audience, both provide festivals of fun, a mélange of games featuring exhibitions by unknown talents, recognized stars, and faded legends. For the players themselves, both provide nothing more than a chance.

For Glenn (Doc) Rivers, the splendid guard from Proviso East High School, they are a chance to hone his skills for the challenges he will face this fall at Marquette. For Frazier, they are a chance to see if the fires burn brightly enough to encourage extension of his already brilliant career. For Gilmore, they are a chance to further test his reconstructive knee. For a number of undergraduates, they are a chance to be seen. For any number of postgraduates, they are a chance to test themselves again. For former Loyola star Tony Parker, for former Northern Illinois star Matt Hicks, for Rickey Green and countless others, they are a chance to remember and to once again hope.

****

“I’d say the European pros still desire, a chance to be seen,” says Shelly Stark, who coaches one of the teams at Chicago State and has been involved in summer basketball for some 20 years now. “Others, who’ve been drafted in the past hope for a free agent tryout from this exposure. College seniors want more exposure.

“For example, Ronnie Lester. Two years ago, Rod Thorn didn’t like him, and now he’s a first-round draft choice. Tony Parker. He says he’s very happy in Europe, but deep down I think he desires another look see. There are an awful lot of players like that.”

“Probably more than half come out to be seen by scouts because they know they’ll be here,” adds former Chicago State star Mike Eversley, who was drafted and cut by the Bulls.” The other half come out to play and have a good time, and I’m in that half. I have hopes, sure, but hopes are like dreams. If they will be, they’ll be. But the competition here is the best you’ll find. You can make a name for yourself, get self-satisfaction. I come out to do well against the best. That’s something I can talk to my kids about.”

****

“The reason I’m doing it is, hey, to be myself, so to speak,” says Billy Harris, the former Dunbar High and Northern Illinois star who will always be “Billy The Kid.” He is irrepressible and glib, and he is now sitting in an office just off the gym and awaiting his chance to perform in the night’s second game. “I don’t think of myself as just a guy who can bounce a basketball. I think of my abilities as God-given. Few can do what I do with a basketball, but it’s not always appreciated. Bach, Beethoven. They did what they did, but when they were alive, no one appreciated them.

“But I’m realistic. There’s not many as realistic as I am. There are a lot here who have the ability to play in the pros. I had more than just ability. I was a talent. But I know that’s not the only reason you’re in the NBA. That’s where the dream thing comes in. ‘Hey, I have the ability.’ Hey, that’s OK. But when you’re Black, poor, and play some kind of sport, it’s not realistic to believe that.

“I’d go so far to say that 75 percent of the guys just out of college, one, two years, they’re all thinking that way or they wouldn’t be out here. I am here because I owe the people. They love my game. But the rest strive for it. I don’t blame ’em. Think of the time you put in working hard for it. Do you get over it? You never get over it. How can you get over it when you can still jump two feet over the basket? Hey, I dreamt of the NBA from the first time I shot a jump shot, ‘cuz that shot went in.

“Think of the mental challenge you go through when you’re finished with your basketball life. How do you expect the guy to spend his character-building years thinking of the NBA and having it cut off, how do you expect him to handle it with a brown bag? If you’ve forgotten how to survive, you can go crazy. If you remember, you’ll make it. The average guy’ll lose his mind. We got guys around here who’ve been in the pros walking around in overcoats, and it’s a hundred degrees out there.”

****

He claims that he has escaped the dream, yet there are times when Rickey Green still sees himself in front of the klieg lights on an NBA court. Those moments occur infrequently, only when he is watching games on TV, but suddenly some guard makes a move and Rickey Green is in his place. “Naah, naah, he shoulda done this,” he might think on one occasion. “I woulda done it that way,” he might think on another.

“I definitely do that,” he says. “Yeah, I put myself out there.”

It is, of course, unlikely that he will ever again be out there, a realization he was able to embrace only after 15 months of false hopes. He festered during the latter part of his season with Golden State, presumed he was gone once that team acquired premier playmaker John Lucas, then was buoyed by the trade that sent him to Detroit and returned him near the scene of his college, glory. “But it didn’t work out with (former Piston coach Dick) Vitale, and then he said some things about me that weren’t true,” Green says. “But they were said, and they kinda hurt me a little bit.”

“There are so many Rickey Greens, kids that shoulda been . . .” Dick Vitale said. “He came with an attitude—‘I am a superstar’—and kept talking how he didn’t get a shot at Golden State . . . That scared me . . . After 17 years coaching, you can see the chip on his shoulder . . . He never got nasty. He didn’t sulk, didn’t pout. And do you know something? I like him. He’s a good kid. But he just didn’t really want to work.”

At lunch at a Near North Side restaurant, as his salad disappears, the mixed emotions that still churn within Green clearly appear. “I believe I can play in the NBA. If someone gives me a real look,” he says at one point.

“If Italy wants to sign me, I will sign. Time’s passed, and I’m not getting any younger,” he says at another. “Charlie Criss (of Atlanta). How many years did he play in the Continental League? Like eight years. So it’s always there if they call your number,” he says later.

“The NBA’s not No. 1 anymore. You have to think of something else or you’ll go crazy,” he says even later.

****

He lays down his fork and sips from his orange juice. “It’s hard to explain,” Green finally says. “You trip on it. You think about it. You try to figure out what went wrong. You go through depression. You can’t remember what you did. You get angry. You wonder why. You get frustrated. But eventually you’ll grow out of it.

“That’s what I did. It’s not just the NBA now. I don’t trip on it now. Some guys’ve been out five, six years, they’re still tripping about the NBA. That’s crazy. I know cats who’re 30 still thinking they’ll get a shot. I say, ‘Not me.’

“Rather than sitting around and worrying about the NBA, you’ve got to do something else. I mean, everybody wants to be in the NBA. It’s the best in the world. It’s everybody’s dream. But dreaming about it grows old, and you just got to move on.”