[In the early 1970s, Mr. Hayes went to Washington . . . after a one-season layover in Baltimore. Gene Shue, then coach of the Baltimore Bullets, traded for Elvin Hayes believing that the Big E was one of the greatest players of that era. Or, as Shue would tell me many years later, one of the greatest forwards ever. Shue believed that teaming the versatile Hayes with the sturdy Wes Unseld would equal a frontline match made in heaven, placing the Bullets on track to win an NBA championship, which turned out to be correct.

But first, Mr. Hayes had to silence all the critics from his mostly unhappy four seasons with the San Diego-turned-Houston Rockets. In this article, the Baltimore Sun’s Alan Goldstein toggles between the critics and the optimists to frame the state of Hayes’ career as he prepared to make good with his second NBA team. Goldstein’s article appeared in the April 1973 issue of the magazine Super Sports.]

****

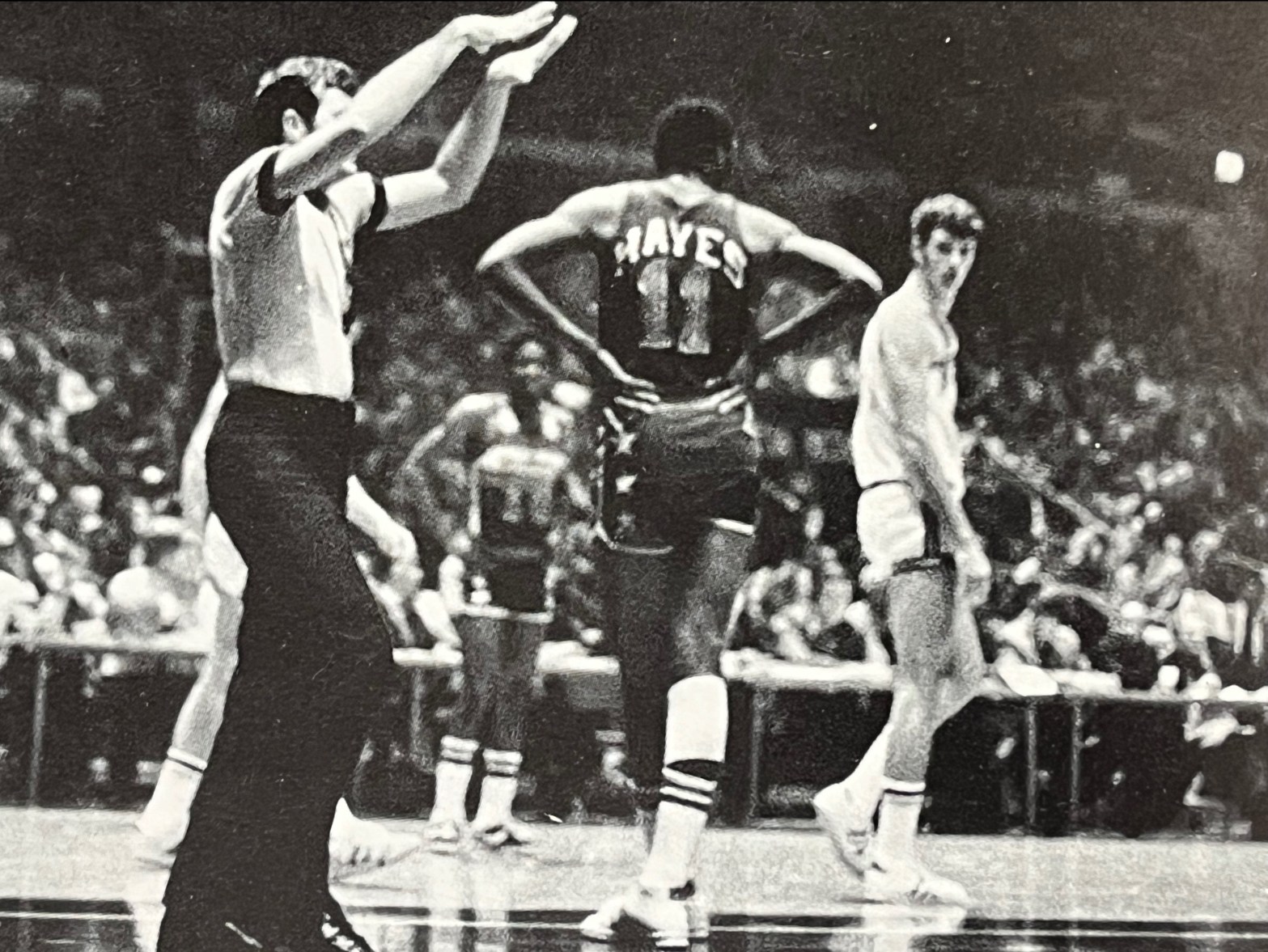

Back in 1968, Elvin Hayes was the College Player of the Year and known as the man who outplayed Lew Alcindor (a.k.a. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) to lead the University of Houston to an upset over UCLA. The Baltimore Bullets, who finished last in the Eastern Division the previous season, had a chance to land the “Big E” by winning a coin flip with the then San Diego Rockets. The Bullets called “heads,” but it came up tails. The groans in Baltimore, led by coach Gene Shue, could be heard in San Diego.

As a second choice, Shue settled for Wes Unseld, the baby bull from Louisville. He won Rookie of the Year (not Hayes) and Most Valuable Player honors his freshman season in leading the Bullets from last to first in the East.

Now, it was four years later, and Shue was asked, in retrospect, whether given another coin flip, he would still have preferred Hayes over Unseld. “I don’t have to answer that now,” he laughed, “because I’ve got both of them.”

Shue, of course, wasn’t joking. He had just completed the biggest trade of the offseason, swapping his high-scoring all-star forward Jack Marin for the 6-9 ½ Hayes, who was rated one of the game’s bona-fide stars.

On paper, it sounded like the biggest swindle since Peter Minuit grabbed Manhattan Island from the Indians for $24 worth of baubles. The obvious question was why then did Houston make the deal? The most logical answer was that Hayes and Rocket coach Tex Winter were incompatible. The same was true, some cynics might say, of Elvin’s stormy relationships with his earlier pro coaches, Jack McMahon and Alex Hannum, who bossed the Rockets in San Diego.

One wag at the Bullet press conference announcing the deal suggested that the “future considerations” meant that a psychiatrist would be included in the transaction to handle Elvin’s many problems.

“I know he’s had some attitude problems,” Shue said in the understatement of the year. “But, as I see it, a lot of players have attitude problems. Athletes can be temperamental. I just hope he’ll be able to adjust his attitude and realize his true potential with us. If he does, we can become legitimate title contenders.”

****

When Elvin finally arrived in Baltimore, he looked and acted about as much like a troublemaker and coach-killer as Little Lord Fauntleroy. After four stormy and frustrating years with the Rockets, the Big E appeared to be the “Most Happy Fella” in joining a team that had been in playoff contention that last four seasons and gone to the championship finals in 1971.

“The players’ attitude in Baltimore is much better,” Elvin said. “This is like a big, happy family here. In Houston, it wasn’t a family.

“In a way, it’s like you’re married to your team. It’s like having another wife. You spend the better part of six months living and playing with these guys. If there’s trouble, you have to solve the problems inside the family.”

The 26-year-old native of Raysville, La. realized there was tremendous pressure on his slender shoulders. He was being regarded as the Messiah who would finally lead the Bullets to the mountaintop. “Sure, there’s a lot of pressure on me,” he acknowledged. “But I’ve always played under great pressure. Now people in Baltimore think we have the makings of a championship team. But the Lakers had two superstars—Jerry West and Elgin Baylor—and never won it. Each guy on the team has to do his job to make us a winner.

“But I’ve always had a great deal of confidence in myself,” Elvin added. “I never accept defeat or the idea that anyone is better than me. I might be ‘burned’ by somebody one night. But the next time, I might ‘burn him.’”

Unfortunately, it wasn’t only the opposing players Elvin burned in his controversial career as a pro. He also burned a few coaches, and Jack McMahon in particular blames Hayes for costing him his job.

“I was fired by San Diego in 1969,” recalls McMahon, “because Bob Breitbard (then Rocket owner) made a choice between myself and his big center. I’d fine Elvin repeatedly for breaking the rules, but the big guy would just go down the office hall and talk to Breitbard. I don’t know if the fines were lifted, because I never saw his checks.”

McMahon also contended that Hayes had an identity problem, sometimes mistaking himself for the coach of the team. “During a playoff game with San Diego in 1969,” McMahon recalled, “Elvin kept criticizing his teammates. He kept yelling at Don Kojis for not doing a better job on the Hawks’ Lou Hudson. I had to take him aside and remind him that it was my job to criticize the players, not his, but five minutes later he was back at it again.”

According to McMahon, Elvin almost became a Bullet as early as 1969. The Bullets reportedly offered Earl Monroe and LeRoy Ellis in exchange. “It was a firm offer,” McMahon insists. “Baltimore was the only team in the league which consistently displayed interest in Elvin. But Breitbard wouldn’t trade him.”

But the trouble didn’t end with McMahon’s departure. When Hannum took over, the Big E still managed to antagonize his less-publicized playmates and cause Hannum to lose a few more hairs of his already shiny scalp.

Hayes’ favorite sparring partner was Kojis, the eloquent forward who used his time between games, keeping a diary on the Rockets with Elvin as his chief character. Elvin reportedly got wind of it, ripped up the diary, and helped create a little more chaos on the team.

When the Rockets went into a particularly bad tailspin in 1970, Elvin, who felt he was doing all he could to turn the tide, branded his teammates “a bunch of losers” and asked to be traded. A few days later, Elvin was feeling apologetic.

“With all the stuff that was written,” he said, “my teammates still care about me, and how do I tell them how much I appreciate that? These guys are all winners, every one of them, not losers. If they’re losers, I’m a loser also. I’m not going to cut these guys down and make myself come out smelling sweet. If they’re dirty, then I’m dirty, too.”

But this didn’t stop the internal bickering on the Rockets. A number of the spear carriers felt Hayes was too intent on being a one-man show. As [Rocket] Toby Kimball said, “It’s the old story—one man can score 100 points, and the team can lose the game. It’s the history of sports: one man can play for points, and the game is lost.”

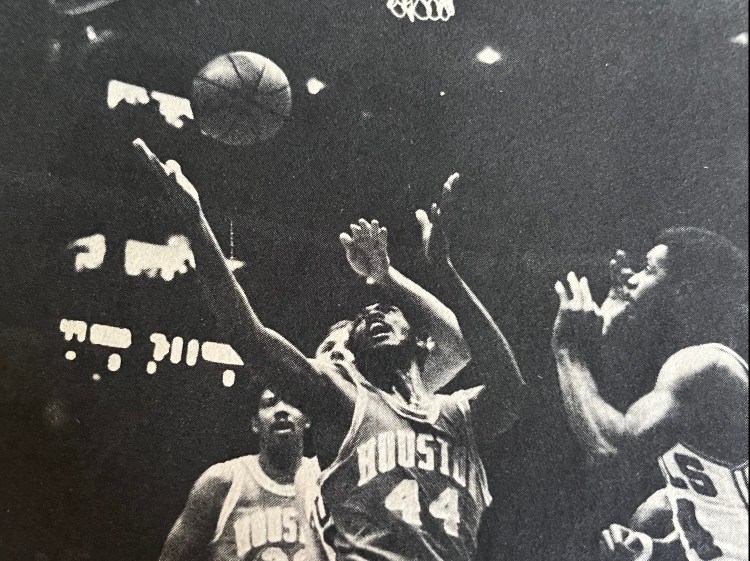

When the Rockets left San Diego for Houston in 1971, Elvin saw it as a new lease on life. He felt he would find peace and harmony in the Texas metropolis where he put basketball on the map as a celebrated collegian.

“I’m glad I’m leaving San Diego,” Hayes said at the time. “Nobody knows me here. I’m just a big hulk of nothing. I head down the street with my wife and baby, and people go right on walking. In Houston, I can work for Judge (Roy) Hofheinz. I can make public appearances, and I can make a lot of money in the off months. But not in San Diego. Nobody will have me.”

But Elvin soon discovered that Houston wasn’t Paradise. He had a winter of discontent playing for the Rockets’ new coach, Tex Winter, who needed only a few months to convince himself that his “marriage” with the star center was quickly headed for divorce.

Hayes, who had averaged over 28 points a game in his first three seasons, saw his average shrink 25.2 under Winter’s style of ball. Elvin also had many mad moments trying to understand Winter’s coaching philosophy.

“I’ve always relied on quickness against the big guys to get my shots off,” he explained. “But Winter had us running a slow set-offense like the Bulls and Knicks. This was a new style for me. I remember my first game last year. Cliff Ray, the Bulls’ rookie center, blocked my first four shots. It took me a long time to get adjusted.”

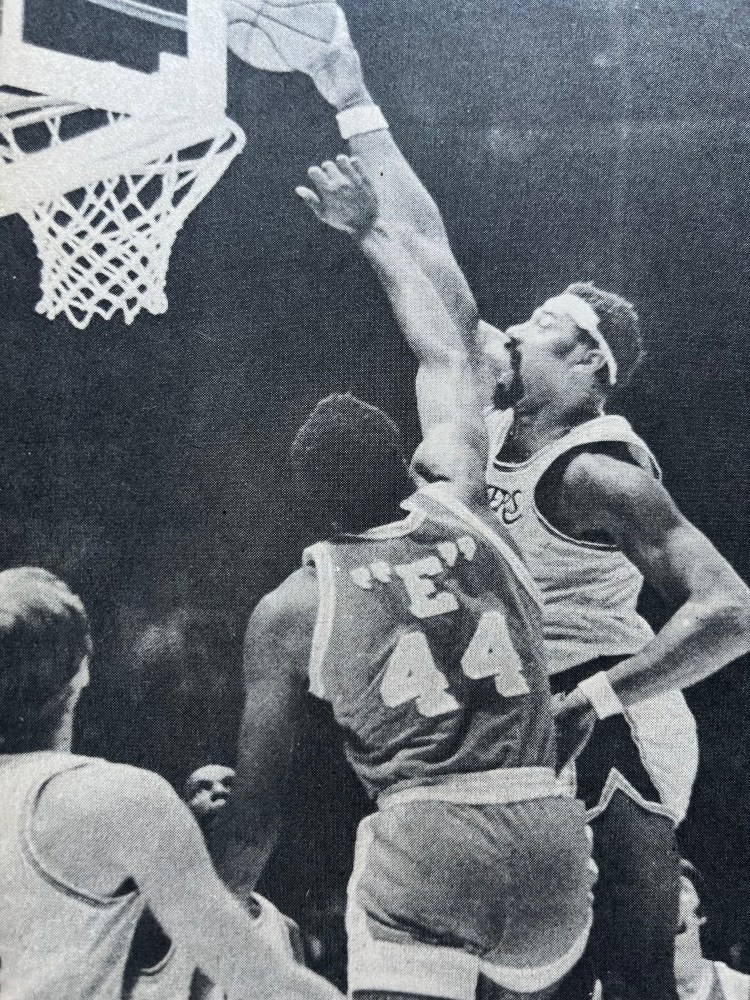

In welcoming Hayes to Baltimore, Gene Shue has tried to take as much pressure as possible off his new star. Originally, Shue had considered the idea of installing Elvin as his new center, shifting Unseld, whom he always considered a perfect forward, to a corner position.

But after several exhibition games and team practices, the Bullet coach had a change of heart. When the season started, Unseld was back at his familiar stand, clogging the middle on defense and playing the opposition’s big man, whether it was Jerry Lucas or one of the legitimate giants—Nate Thurmond, Wilt Chamberlain, or Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

On offense, Unseld was again positioned in the low post, while Hayes roamed around the foul circle looking to get off his near unstoppable jump shot. “Elvin is a great offensive machine,” Shue said, “and I want him to feel free to ‘do his thing’ when we have the ball. Defensively, he is the best shot blocker we’ve ever had. I think he’ll block even more shots as the weak-side forward. He can switch off this man and get the shooter coming through.”

Hayes was obviously happy with his new situation. Elvin’s carefree attitude was also a result of a new five-year contract that he signed with the Bullets calling for a reported $250,000 a season. When the Bullets acquired him from the Rockets, he still had seven years remaining on a 10-year contract he signed in San Diego in 1969.

But his attorney, Al Ross, persuaded the Bullets to renegotiate. “We didn’t think it was valid,” Ross explained. “Elvin wasn’t properly represented. People acted in his behalf as his friends, but it turns out they were acting in their own interest.

“Elvin didn’t have any security for himself or his family in case of injury. There was so much deferred compensation. When he signed, the Rockets told him he would never be traded and the team would never leave San Diego. So he went into the restaurant business there and bought a house. But they didn’t keep their promises. It was highly inequitable.”

Ross found the loophole he needed in discovering a California labor law that restricted personal services contract to seven years. “If the Bullets had refused to renegotiate, we would have taken it to court, and, I’m certain we would have won,” Ross said. “But we didn’t want to spend the next two years litigating his contract. Elvin believes Baltimore will be a contender, so it was in his best interest to sign.”

Even at $250,000 a year, the Big E isn’t one of the top-paid players in the league at today’s inflated prices. But Hayes realizes he has come quite a ways from his days as a timid youngster in Raysville, La., where he was forced to work at an early age because of the death of his father.

“You know, I never had shoes until I was a freshman in high school,” he recalls. “I‘d always go barefooted. I remember once I was going somewhere to a football game, I think, and I had to borrow a pair of shoes from another boy. I was always borrowing some shoes. But this kid wore 11, and I wore a 12. They crammed me so much I had to walk with my heels out of them. That was the most miserable day of my life.”

But Elvin also remembers the long, hot days of toiling in the cotton fields back home. “I was picking cotton when I was eight years old,” he says. “When I got older, I was picking and chopping cotton from four in the morning until noon without a break, and you’d make four dollars or five dollars for your troubles.”

And Elvin also had to work just as hard to become a basketball star. He was anything but a natural, failing to make the Eulah Britton High squad as a freshman or sophomore. He hung the wash bucket on the wall and, in the summer, would practice shooting from nine in the morning until bedtime. “Sunday was out,” said Elvin. “My mother said I couldn’t play then.”

But basketball is now Elvin’s livelihood, and he has become one of the best at his trade. Still, he carries the stigma of being a “loser” and “malcontent.”

He knew he had something to prove this season in Baltimore. Leading the Bullets to a championship would be the best way to silence his many critics. That’s why in 1972, the Big “E” stood for Effort.