[No need to waste space here introducing Julius Erving. The name still speaks volumes, and the prolific, Philadelphia-based journalist Dick “Hoops” Weiss fills in nicely throughout his story the myriad issues faced by the 1980 NBA version of Erving. Weiss’ timely overview ran in the December 1980 issue of the magazine All-Star Sports’ winter basketball issue. It’s definitely worth the read for the many Dr. J fans out there.]

****

Perhaps the worst mistake Julius Erving made since becoming a member of the Philadelphia 76ers occurred three years ago. The autumn after the Sixers had lost to Portland in the NBA finals, the brilliant 6-7 All-Pro forward was talked into recording that now infamous television commercial, the one that ended with an IOU.

“And remember,” the Doctor said, “we owe you one.”

The fans remembered all right. And they never let Erving and the rest of his teammates forget they owed us not just one, but two, then three world championships.

This past season, the Sixers finally started to pay off their outstanding debts, beating hated Boston in the Eastern Conference finals, then splitting games with LA on the coast before finally collapsing to the Lakers in the championship round.

Los Angeles won the deciding game of the abbreviated series, 123-107, at the Spectrum in Philadelphia, making up for the fact that 7-4 Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was some 3,000 miles away recuperating from a sprained ankle by summoning up a superb 42-point performance from splendid rookie Magic Johnson.

Pow. It was an unexpected shot to the head. “I guess the fans will swing over to the Flyers now,” Erving said in retrospect. “I may be an eternal optimist, but I am also a realist.

“I can’t say I blame them. I expect disappointment. And animosity. The best thing we can do is meet that head on and make people understand that nothing is guaranteed. And then we have to come back next year and work as hard as we can, and if they accept us again, fine. If they don’t, that won’t exactly be a new situation either.

“But I am not going to let losing in the finals negate all the things that we did accomplish this year. We won 59 games in the regular season, and I honestly believe we can win more next season. I am looking forward to next season. When we lost in 1977, I wasn’t. This time, I think we are in an ascending position.”

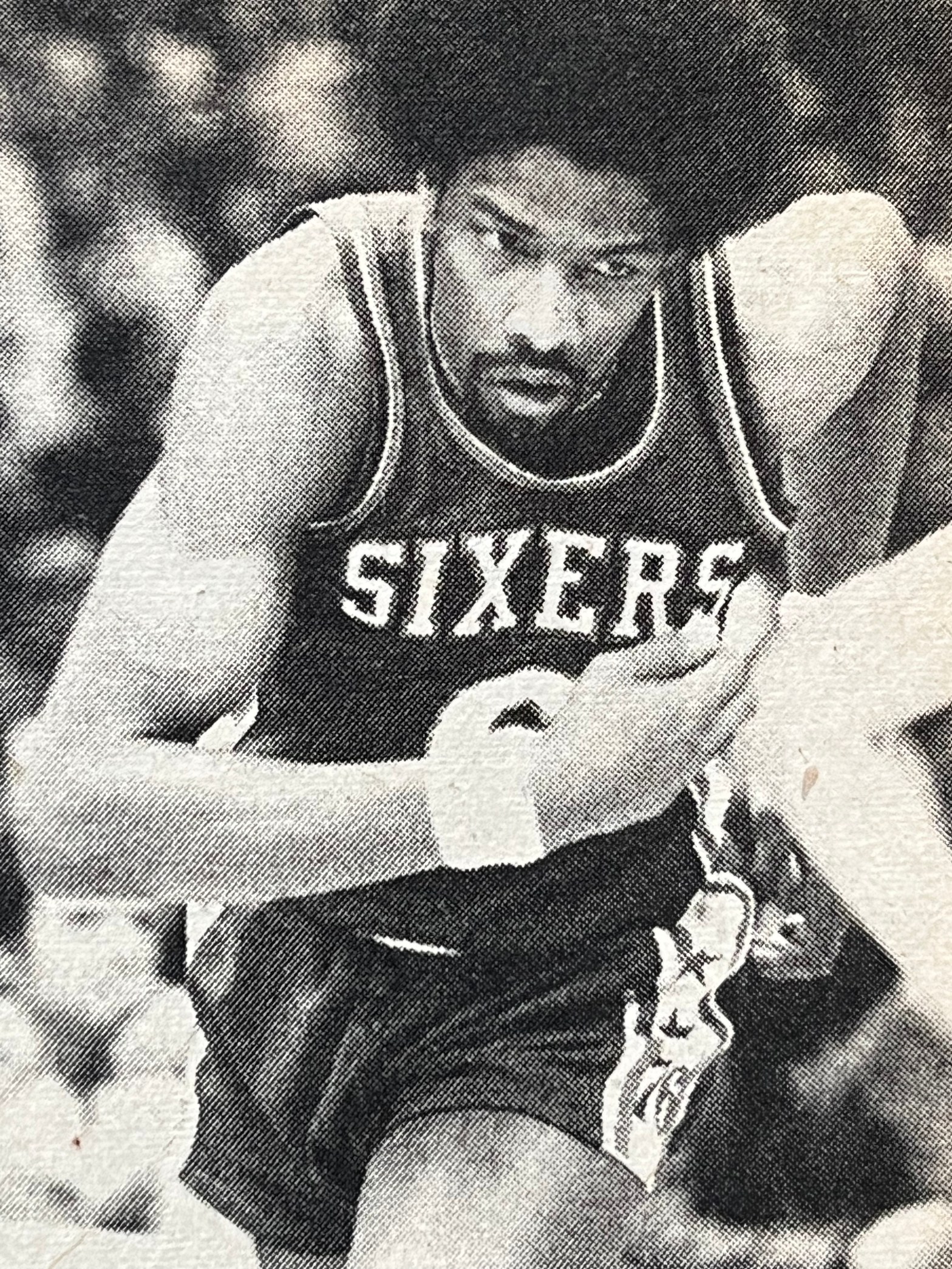

Julius Erving’s star certainly has risen back to the brightness that it once knew when he was Dr. J of the American Basketball Association. “Julius Erving,” says his coach Billy Cunningham bluntly, “is the greatest forward ever to play the game.”

He is certainly the most exciting. Erving’s statistics during the regular season—26.9 points, 7 rebounds, 4.55 assists, and 2.18 steals a game—can stand on their own merits. But the uncharted, explosive quality of his game is best seen through a movie projector, preferably one that is equipped with slow motion, stop action.

How else can we best understand the beauty of the Doctor’s windmill slam dunk over Dave Cowens, Rick Robey, and Larry Bird in Game 3 of the Boston series? Or truly appreciate Erving’s 15-foot finger-roll in Game 3 against Los Angeles?

CBS network television did manage to preserve one of Erving’s magic moments on camera, catching his near impossible baseline layup in Game 4 of the Lakers’ series. This was one play that is difficult to describe if you restrict yourself to words in the English language.

Simply put, though, Erving defied gravity, taking a baseline route to the basket. The Doctor floated along the out-of-bounds line, around Jim Chones, Mark Landsberger, and the menacing 7-4 Abdul-Jabbar. Then, he reached from behind the backboard, flicking in an impossible shot. “It’s gotta be in his top five moves of all-time,” Cunningham said later.

Just another day at the office. Erving scored that classic field goal with 7:35 to go in the fourth quarter, adding eight more points before the end of a 105-102 victory at the Spectrum. Yes, he completely took over the game when he had to, the same way he had taken it over whenever the Sixers sent out distress signals this past year. Make no mistake about it, even though the Sixers were probably more team-oriented than ever before, this was Julius Erving’s team. He was the flight pilot on this lunar mission.

Last year, when the Sixers were struggling, Erving had almost dropped off the radar scope. Writers throughout the country took a microscope to his game and found that he had heretofore present, but always unnoticed, flaws in his perimeter shooting, ballhandling, rebounding, and defense.

“I still remember reading an article by a guy from Sports Illustrated,” Erving said. “He said I was a struggling forward on a mediocre team.”

The words obviously stung the player who was once an ABA legend when he played for the New York Nets. “They took a shot,” Erving said. “It was just one of a series of shots people had taken. That’s really neither here nor there now before yesterday’s news is old news. Whether you feel it’s unfair or not, sometimes you don’t have any recourse except to go out and prove yourself. I know the opinion of that writer was not shared by everyone. But when you write for a national publication, a lot of people believe everything they read.

“And so for the first time, at the beginning of the season, I think I started to put more stock in statistical achievements. Not that I’ve become a freak about stats. But obviously, I’ve become a little more conscious of them, because stats in a lot of cases are a measure of how you are rated.”

Erving is the first to admit that stats have been the downfall of many players in this league. “In my nine years [as a pro], I hated to see guys just going and playing for stats,” he admitted. “I can’t stand to see a guy looking at a stat sheet at halftime, looking at how he’s doing when his team might be losing by 20 points. If I were the coach, I’d be really bleeped off.

“But this season, because of some of the hard knocks I received, I would analyze the stats in the locker room after the game, try to establish some level of individual achievement within the context of what we were doing as a team, so I would have my defense ready to throw out at the critics.”

Erving’s defense is right there in black and white. During March alone, he averaged 29.8 points and shot a blistering .616 from the field as the Sixers battled Boston for the Atlantic Division regular-season championship. His statistics were so dominant that he received a $10,000 check from Seagram’s for winning that company’s annual Seven Crowns of Sports competition as “the most consistent and productive” player in professional basketball.

The Seagram’s award evaluates every NBA player on the basis of overall achievement and consistency during the regular season, specifically on the ability to fulfill the responsibilities of an individual position. Seven major categories are analyzed to determine a player’s so-called Productive Efficiency Rating: scoring, shooting accuracy, free throw percentage, rebounds, assists, steals, and blocked shots. The last two areas provide a strong indication of a player’s defensive contribution to team effort.

A standard of achievement table has been established for the three positions—guard, center, and forward—and players are measured only in terms of their position, not against their positions.

Erving, the fourth-leading scorer in the NBA this season, was the second-leading scorer among forwards. He led all forwards in steals and was third at his position in assists. “In the past,” Erving reflected, “the guys who won the award were normally fantastic scorers. Robert McAdoo was a scoring champion. George Gervin was a scoring champion for two seasons in a row.

“Hopefully, in my case, the award was not just for my ability to put the ball in the hole, but for the contributions I was able to make to our team, both offensively and defensively.”

Not surprisingly, Erving donated his check to both his mother and his mother-in-law. That is typical of the man.

Erving probably handles being a superstar better than anyone in pro sports today. He has always had time for both the press and the fans. And he goes out of his way to speak kindly of the organization. “Right now,” he said, “I think I can really celebrate my move to Philadelphia.”

That was not always the case. When Erving first arrived on the scene in Philadelphia, he was viewed somewhat as a mercenary, a player who sold out to the highest bidder when Nets owner Roy Boe put him out on the open market after failing to successfully renegotiate his contract. In 1976, Erving signed a six-year contract with the Sixers, then coached by Gene Shue, for the tidy sum of $6 million. “The circumstances of my coming to Philadelphia were not ideal,” Erving recalled. “My contract was sold to Philadelphia. I did not elect to come here. I did not say, ‘I want to be traded to Philadelphia.’”

Erving was forced to spend two years in purgatory, playing on the same teams in 1977 and 1978 with all-stars Doug Collins and George McGinnis. The Sixers during those years were a flying circus, a gallery of stars who reached the finals one year because of their overwhelming mother lode of talent. That year, however, Portland had both a healthy Bill Walton and a healthy dose of discipline, the two necessary ingredients that combined to put the Sixers in their place.

Now, most of Gene Shue’s sideshow has been dismantled. McGinnis is back home in Indiana, by way of Denver. Lloyd Free is pumping up rainbow jumpers in San Diego, along with Joe Bryant. And even the once-mercurial Collins was nowhere to be found on the active roster this March, sidelined by a painful knee injury that he suffered two weeks before the end of the regular season.

In fact, four members of that 1977 team—Erving, Caldwell Jones, Steve Mix, and Henry Bibby—were around when the renaissance started in training camp. During those first practices, Erving, who tried only to fit in during his first three years here, was taking command.

He was on the verge of turning 30 years old. But, for the first time since his immigration to the NBA, he was completely healthy. “After our last game with San Antonio in May of 1979, a game we lost, I dragged myself home, dragging my leg. The stomach muscle was gone, the groin muscle was pulled. Had we won the quarterfinal series, I couldn’t have played against Washington without an injection.

“I went home and rested. Then, starting June 1, I started therapy to get myself together. Get the groin muscle healed. Get me as healthy as I possibly could be. It was something I hadn’t felt for a long time. I had been on a merry-go-round. My way of resting in the past was taking a couple of trips, playing some tennis,” said the Philadelphia star.

“Well, the first time I attempted to swim, I couldn’t kick. If I couldn’t swim, and I couldn’t play tennis, there goes the summer. When I first started therapy, I couldn’t lift any weights. Not one pound extra. I couldn’t hold it for the required seven seconds. So I worked, three times a week, three hours a day, with a team of physical therapists, headed by Joe Zohar of Long Island. They brought me along very slowly through the next two months.”

By August, Erving was able to run again, working himself up from a quarter mile to two miles. By the start of camp, he was so strong that he didn’t bother wearing those ugly braces on his once aching knees.

Erving flew into the season. His superb physical condition may have been one reason that Cunningham allowed him a green light offensively. To his credit, Erving never abused that privilege. He was always conscious of constantly involving himself in the team’s offense.

“People look at my first three years in Philadelphia,” he said. “I averaged 21, 22, 23 points a game. They should also look at the number of shots I’ve had, situations where I’ve sat, games decided in the third quarter. I’m not going to be a gunner, but the quality of my game concerns me.”

Erving established himself quickly this year, getting 28 points on Bobby Dandridge during the Sixers’ opener against Washington at Landover, Mary. The next night in Philadelphia, he ripped Houston for 41 points.

When Lou Schienfeld, the team’s new president, arrived here in February, he was so impressed by Erving’s ability that he came up with the idea of offering him a lifetime contract. Of course, with Scheinfeld’s background in public relations, this could easily be viewed as a cheap stunt to get the apathetic fans in the Sixers’ corner.

But Schienfeld views this as a chance to make sure No. 6 does not leave town when his contract expires two years down the road. “I would like to see Julius in a Sixers uniform until the day he retires,” Schienfeld claimed. “We would even consider offering him an executive position with the team after he finishes his career if those were his wishes. It’s obvious to me, we need to have people like Julius in our organization.”

Schienfeld has since gone on to say that negotiations to bring about this version of eternal life will continue through the summer. If the Sixers were interested, they may have to open the bank vault. Erving is now worth at least $800,000 in today’s inflated market.

Of course, there are some people who claim Julius Erving is priceless. “He is the man,” said teammate Darryl Dawkins. “Don’t anybody forget it.”