[More Julius Erving, so no long intro needed. This article offers the popular columnist Mitch Albom’s take on the 34-year-old Dr. J as the best thing in pro basketball during the early 1980s. Though Albom is remembered best for his outstanding work in Detroit, he wrote this story for the Fort Lauderdale (Fla.) News, where he was a staff writer on April 23, 1984. All you Dr. J fans out there, enjoy!]

****

Julius Erving is the best thing in pro basketball today.

Now please, hold your fire. No one is debating the sky hook of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the dead-eye shooting of George Gervin, the all-around play of Larry Bird, or any of that stuff. But with Julius Erving, we’re talking a non-statistical category.

Mass appeal.

The kind that sells out visitors’ arenas. The kind that makes TV executives drool. The kind that makes kids holler, “Doctor J!” as they leap toward makeshift baskets. The kind of appeal that keeps a sport alive. The kind pro basketball needs in the worst way right now.

Mass appeal.

Follow Julius Erving to an afternoon practice at a local Philadelphia college. Kids are waiting at the door. He says, “Hey, fellas,” and they fall in line alongside him. A young woman stops him for just one snapshot (she takes three). Before he gets to the locker room, two reporters and a TV anchorman grab him for interviews. When he emerges in a red tank top and white shorts, he is corralled for a video session with a large, furry green creature called the Philly Phanatic. He stages a brief game of one-on-one. “Cut. Thanks, Doc.” The creature gives him a bear hug. The kids giggle.

Mass appeal.

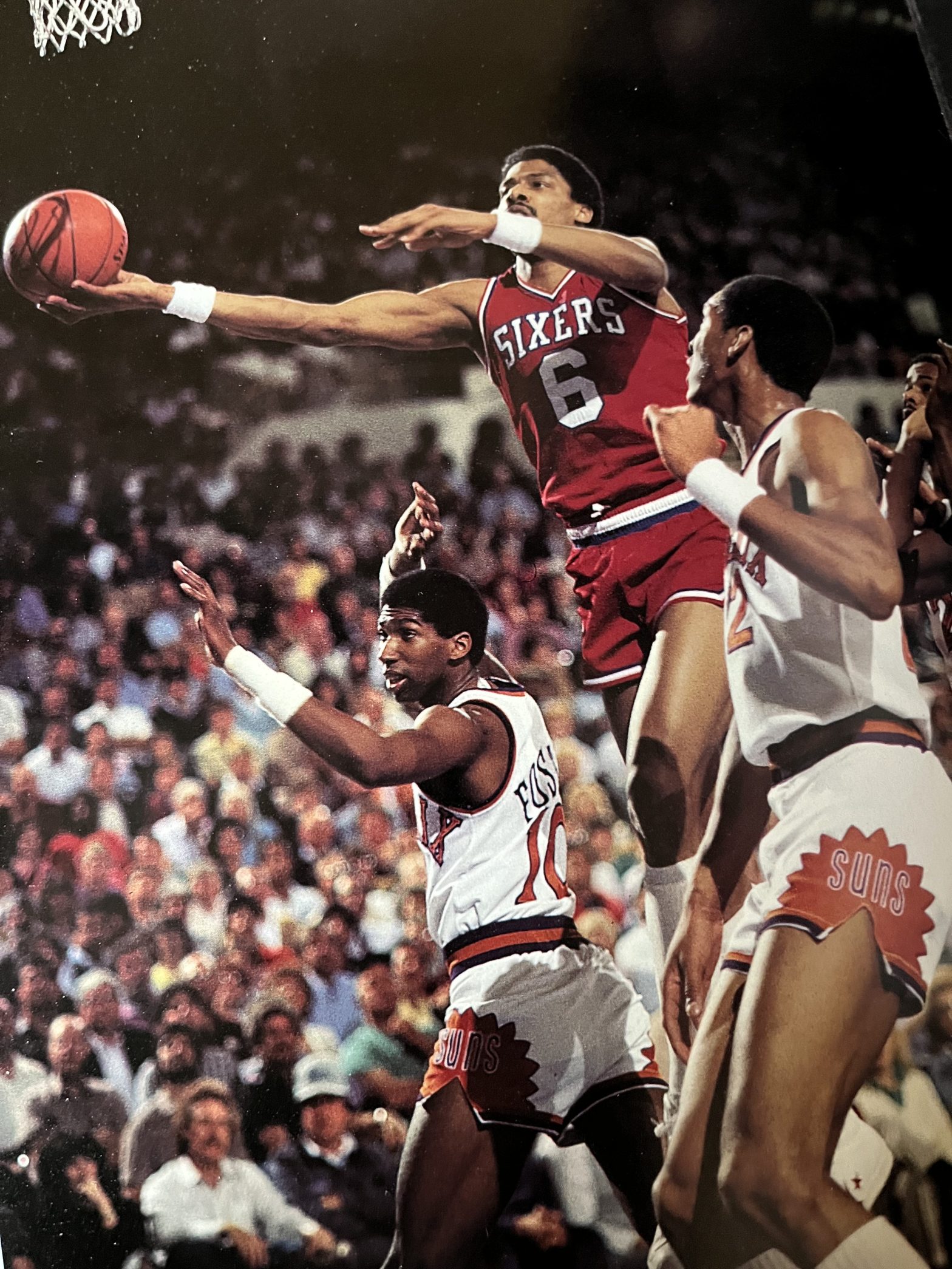

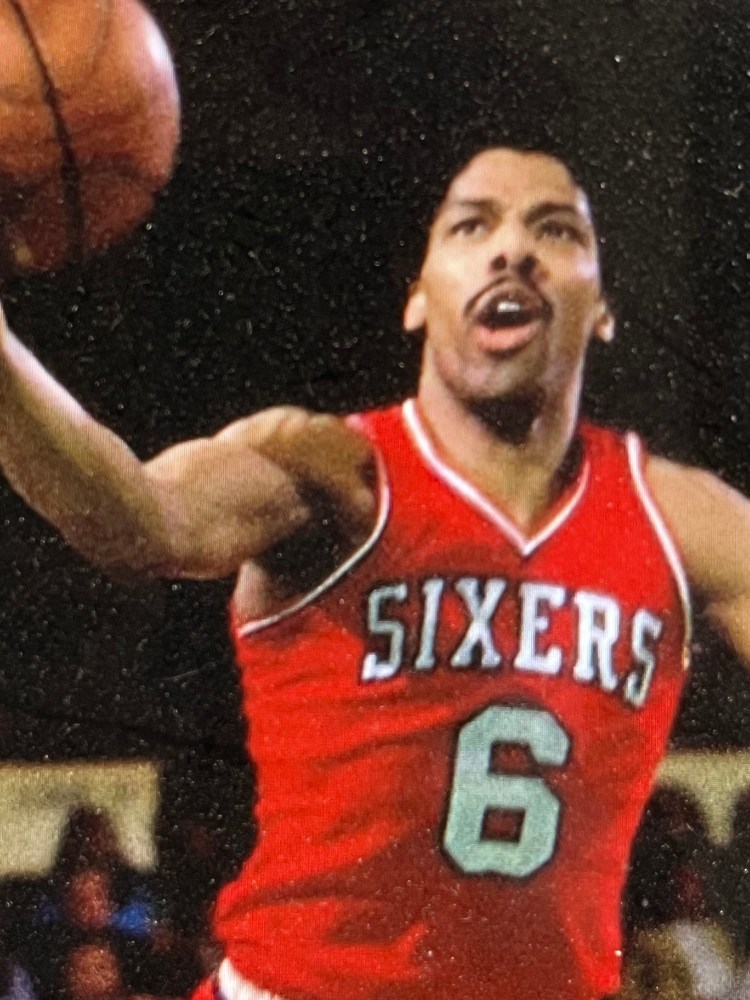

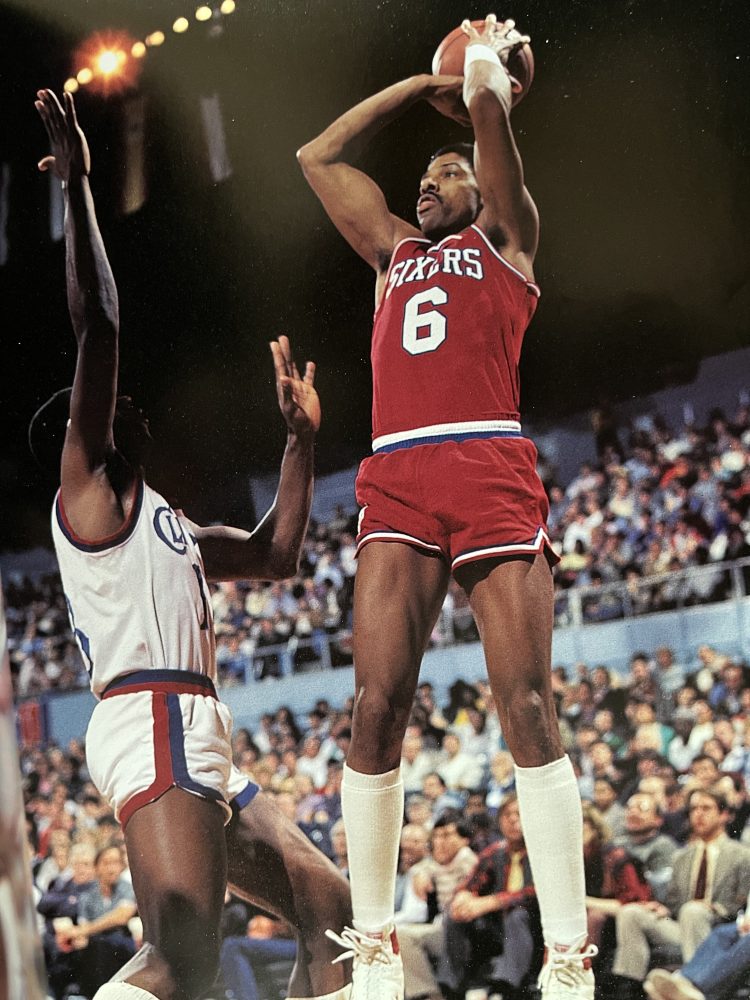

Follow him to a game at the Philadelphia Spectrum, where the announcer always saves his name for last—” . . . and at forward, 6 foot 6, from the University of Massachusetts, Jul-i-us ERRRRRVING!” The place erupts. Two minutes into the game he takes a lob, pirouettes toward the basket, and delicately rolls the ball through the net. Thirty seconds later. A steal, two dribbles, and a flight that commences at the foul line and concludes with a slam through the quivering rim.

“Ooooh,” says a blue-haired grandmother, “that Doctor fellow is very good.”

“Ooooh,” says a 12-year-old kid. “Doc’s so baaad.”

Mass appeal.

Sit by his locker after the game. Reporter after reporter. From Time Magazine to a 15-year-old high school journalism student. Every question gets a pause, then an answer. The pause is to think. “If you’re going to give of yourself,” Julius says, “give fully.”

Mass appeal.

Now take the overall game of pro basketball—if you can find it. Out of 943 regular-season games, network television shows eight. Nine of 23 teams couldn’t draw 10,000 fans a game this year. The players have a nagging reputation for big egos, big salaries, and big problems. Drug incidents have grown so frequent that the league adopted a “get-caught, get-out” policy to save face. There’s been an undertow of racial prejudice for several years and a rap for being a game that you can watch “for the last two minutes of the fourth quarter and not miss anything.” Trying to spur interest, 16 of the 23 teams in the league are now invited to the playoffs—four of this year’s entries have losing records—and much of the sports world is laughing.

Mass appeal. The NBA needs it. Julius Erving has it. The best thing in pro basketball, he is. And there’s one good reason.

Everybody loves him.

“When I was in high school, there was this guy who played football on our team, and I mean, this guy could run the football. He scored three to four TDs every game. But he had the biggest ego, always bragging about himself, never giving credit to teammates or coaches. It was such a disgusting situation. I could see what kind of target he made out at himself . . . Partly because of that experience, I always chose the other route. Let your actions bring you to center stage, not your conversation . . .”

What is it that appeals to us about Julius Erving?

There is, of course, his basketball ballet, so enchanting that he’s been awarded an honorary doctorate in dance from Temple University. “The rest of us play,” says a teammate. “Doc flies.” So poetic are his moves that the biggest homer doesn’t mind clapping when Erving scores against his team. Applauding the Doctor, after all, is just a form of art appreciation.

Then, there is Erving’s seven-year quest for an NBA title—painfully thwarted until last season. Everyone knew what a championship ring meant to Julius. But it kept slipping away. With each Philadelphia playoff elimination—and the losses were constantly gut wrenching—Doc became more humanized in our minds. Such a great player, but no glory. We empathized. He waited. When the 76ers beat the Los Angeles Lakers in four straight last May, it seemed like divine retribution. Everybody was happy for Julius, even the Lakers.

There are other factors that draw us to the man. He deftly walks a line between downtown slick and uptown elegance. “Doc can deal in any world,” said Darryl Dawkins of the New Jersey Nets, alluding to Erving’s hero status to both blacks and whites. Jazz musicians compose songs to Doc’s funky style. Businessmen admire the way he invests his $1.5 million-a-year salary.

He is handsome and well-proportioned (6-6, 210 pounds), not a gawking skeleton like some basketball giants. “I want a picture with Julius,” said a teenage girl waiting outside the Spectrum last week. “You know, he’s so fiiine, I can hardly take it.”

Still, what most appeals to us about Julius Winfield Erving II, the grandson of South Carolina sharecroppers, is his quiet confidence. Superstars who boast embarrass us for rooting for them. Superstars who deny their talent lose us with modesty. Julius Erving does the things we wish we could do with a basketball and comes off the court like the rest of us come home from work.

“Playing basketball well doesn’t make me any better than you or the guy next to you,” he says, “or any worse.”

In our heart of hearts, this is the way we want our sports heroes to treat us.

“I cringe a little when I hear guys interviewed, and they just sort of ‘uh-huh’ their way through . . . To me, a chance to talk with a reporter from Time or Newsweek is not something you should take casually. You shouldn’t do it while you’re lathering up to go into the shower and just blurt out a few things that can be taken in 12 different ways . . .

“You’ve got to be careful. If there’s any room for misinterpretation for what is said, I’m not going to jump into it. I’m not going to leave that room . . .

“My image, I sense, has become more marketable in the last five years. In the first five years, the only thing I was asked to do was public service spots. I was sort of flattered that they asked . . . now the offers are such that if I don’t put the reins on it and act more intelligently, I could find myself spread way too thin. I probably already am . . .”

What does Julius Erving mean to the NBA right now?

“You couldn’t begin to measure it,” said Pat Williams, general manager of the 76ers. “The TV ratings, the TV sales, the image. How can you put a dollar figure on it?”

You can’t, really. But if you’re CBS, the network of pro basketball, you know it’s a bread-and-butter figure. Since 1981, CBS has had to cut its number of NBA broadcasts in half, as viewer interest declined sharply. It is no accident that of the eight regular-season games shown this season, three featured Philadelphia. Last year, it was three out of seven. In 1980-81, it was seven out of 14.

“The way it works is like this,” said Ted Shaker, executive producer of The NBA on CBS. “Turn on the TV. ‘Who’s playing? It’s the 76ers. Oh good. I wonder what the Doctor will show us today.’ With Erving’s talent, the viewer sits there always in anticipation of some remarkable feat.”

They usually get it. A rise above the rim to slam back a shot, a swooping dunk that rocks the backboard.” From a TV point of view,’ said Shaker, “Julius Erving is almost too good to be true.”

“Sometimes I’m out there and I plan a move, and I’m able to execute it. But then there are other times I go for a drive, and it’s not until I’m running down the court the other way that I say to myself, ‘Hmm, did I just do that?’ But I never know till I go up . . .”

This week, Doc and his Philadelphia teammates are completing the first round of the NBA playoffs. And just as a Super Bowl network prays for the Dallas Cowboys, so do the CBS brass keep fingers crossed for the Philadelphia charge. “We can’t play favorites,” said a diplomatic Sharker. “But let’s just say, we’d be very happy if Philadelphia made it to the finals.”

So too, it seems, would the NBA. Its image has been smeared by cocaine busts, contract disputes, and players who can barely mumble through postgame interviews. Erving, by contrast, is a splash of mountain water. No drugs. Articulate to the max. A religious man who hasn’t lost his cool. That rarest of animals who can rock the house like Elvis, then slip quietly home to his wife and four kids.

“You take his graciousness, warmth, and concern, and couple it with his distinctive playing style,” said Williams, “and you’ve got a combo the world doesn’t see much of.”

In truth, few players in NBA history have commanded the overwhelmingly positive attention of the Doctor. Sure, Chamberlain drew fans—but many came to vilify him. Bill Russell was great, but often perceived as a brooding giant. Oscar Robertson and Bob Cousy had the moves but never the intimidating presence. Elgin Baylor had Doc’s flamboyance, but lacked his subtlety. Jerry West, John Havlicek, and Elvin Hayes were loved at home but sometimes loathed on the road.

Erving is idolized wherever he goes, in cities and foreign continents. “His name is worldwide,” said Williams. “Europe, Africa, South America. They all know Doctor J. The only place I’ve ever seen him go unrecognized is mainland China.”

“I can’t forget where this all started, just playing out in Long Island, two on two or eight on eight or crazy ball. And I know that just as one can rise from that position to, say, something where I’m at now, so can one decline from that position very fast . . .

“I understand the cycles of sport. You can play a certain number of years and then suddenly you’re out of the spotlight. You’re treated differently. But then, people who judge me only by what I do on a basketball court don’t know me, and they won’t know me when I’m not playing . . . those are people who won’t let you be human. Even when I try and say, ‘No, I didn’t really make that play’ or ‘Nah, you’re the greatest,’ and all that. So a lot of what I hear, I can’t let make my day . . . The fact is, it hasn’t all been apple pie and ice cream . . .”

Mass appeal.

It is not something a young Julius Erving was counting on. His father walked out of their Roosevelt, Long Island, home when Julius was four years old, leaving him, his older sister, Alexis, and younger brother, Marvin, under the care of their mother, Callie Mae Erving, who has since remarried.

When Julius was 11, his father was struck by a car and killed. “Even though he hadn’t been around,” Erving once told Sports Illustrated, “now there was no chance he ever would be.” That ended what Erving calls “the first phase” of his life.

Then, in 1969, while Julius was a freshman star at UMass, his brother fell victim to Lupus Erythematosus, a disease in which antibodies deadly to the body’s own tissues are produced. Julius last saw his brother during spring break of that year. No sooner had he returned to school then he was called back home. His brother died before he got there.

“That,” he said, “was the end of phase two.”

Phase three was the “merry-go-round” of pro basketball success, the stellar years in the ABA—three scoring titles, two MVP awards, two championships—and the highly controversial jump to the NBA in 1976. (In a bitter dispute after the merger, Erving held out on his ABA New York Nets contract, which paid $350,000 a year. The Nets eventually sold his rights to Philadelphia of the NBA for $3 million.)

“If you ever wondered how crucial Julius is to the game,” said Williams, “just look at that incident. His personality kept the ABA alive. He practically merged the two leagues single-handedly.”

As a player for the 76ers, Julius was a star in his first year, winning the MVP award in the 1977 All-Star Game. He had a six-year, $3.5-million contract. He had more adulation than he ever dreamed possible.

He had no idea where he was going.

“For those first 29 years, I didn’t know why when I dunked the ball, it was any different than anybody else. Or why when I did good things, they were looked at as being bigger than they were, and when I did bad things, they were so quickly forgiven . . . It was all too easy. I hadn’t done it by plan, but here people were coming and asking me for advice. They’d say, ‘Why is your life as it is, and my life isn’t like that? I want it to be like yours.’ I couldn’t tell them . . .

“Five years ago, I went to a family reunion, and my Uncle Alfonso put it in perspective. He said, ‘Somebody along the line really laid a blessing on you.’ Somehow that made everything so much more sensible. I got more interested in the Bible and spiritual fulfillment . . . That didn’t mean I had to become a preacher. I’ve never been that way, and I haven’t been asked to do a 180-degree turn. But it helped me fill the void that I felt. Now I’m much more at peace with myself . . .”

Erving’s status only grew with his NBA tenure. He was chosen the league MVP in 1980-81. And his patience with a cast of ball-hogs, such as Lloyd Free, George McGinnis, Joe Bryant, and Dawkins (eventually dismissed by the 76ers in favor of players like Bobby Jones and Moses Malone), strengthened his reputation as the rarest of sports types—a superstar in the guise of a team player.

He is 34 years old now. He has won the NBA title. If things go according to plan, 1985 will be his final season. It’s a cause for concern inside the game. “We’ve already spoken about what’s gonna happen when Julius retires,” said CBS’ Shaker. “We’ve wondered what we’re gonna do, who’ll come along to fill his place in the game.”

The answer? A shrug. “We don’t have an answer.”

Mass appeal. You can hear it right up the line.

Ask Erving’s younger teammates, like 24-year-old Wes Mathews. “He’s like a big brother, the role model every kid wants to follow.”

Ask his former teammates, like Lionel Hollins (now with Detroit): “When we were losing in the playoffs (1979-1982), he’d come back each training came and say, ‘Hey, falling short doesn’t make you less of a person. Let’s keep things in perspective.’ And we’d come back and win 60 ballgames.”

And his coach, Billy Cunningham: “There’s no better team leader than Julius. He does things quietly, and everyone takes their cues from him.”

Ask his general manager Williams: “When Doc goes, we’ll lose one of the greats. His image, what he does for the game, we’ll never replace.”

Mass appeal.

Ask the TV people, or the folks at Coca-Cola, Converse or Spalding. Ask the legions behind the Lupus foundation, Muscular Dystrophy, or the numerous Christian organizations he chairs and supports.

Ask the people of Philadelphia. And while you’re at it, ask the folks in Boston, New York, Washington, and every other city that should logically root against a Philly ballplayer.

Ask basketball fans and basketball critics. Those that will watch the playoffs, and those that won’t when the 76ers aren’t involved.

Ask them in Munich, Rome, Nigeria, Colombia, Canada, Greece, and Russia. Ask them who is Doctor J? And they’ll tell you true.

He’s the best thing in pro basketball today.