[These days, the first round of the 1986 NBA Draft is most remembered for its tragic figures, from Len Bias and Chris Washburn to Roy Tarpley, John Williams, and Pearl Washington. But the first round also launched some notable NBA careers. That includes the seven-foot “Goliath” Brad Daugherty, the draft’s top pick, who spent eight productive seasons with the Cleveland Cavaliers. Among his achievements: All-Rookie first team (1987), third-team All-NBA (1992), five-time NBA all-star.

As recounted in Terry Pluto’s book Vintage Cavaliers, Daugherty should have landed in Philadelphia 76ers, who had its eyes fixed on him and held the No. 1 pick. But the 76ers, struggling to make ends meet, couldn’t afford Daugherty and his projected whopping salary. Aware of Philadelphia’s financial woes, the Cavs’ moved in and traded up, handing over $800,000 in cash and their high-flying, young forward Roy Hinson (soon to be flying at a lower altitude in Philly because of his cranky knees).

In his book, Pluto describes nicely what it was like with the well-schooled, rookie Daugherty lumbering around the paint on offense:

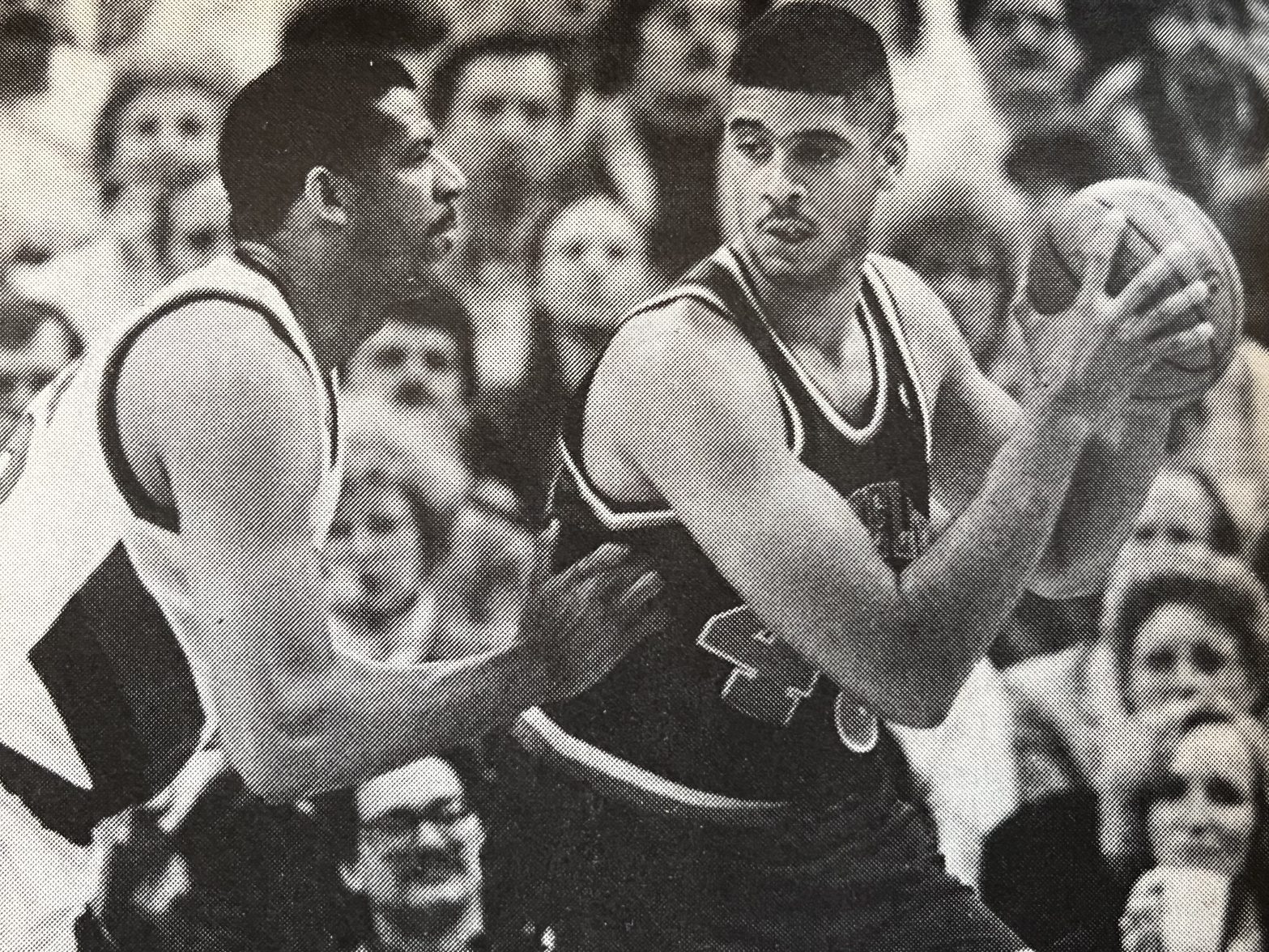

The Cavs were trying to construct a team with no superstar, but a group of high-character, unselfish and very talented players. Six-foot Mark Price looked like he was a senior in high school, not a 24-year-old in his second pro season. I watched him dribble the ball up the court. As he reached the top of the key, Brad Daugherty came from under the basket to set a pick.

The 7-foot Daugherty was only 22 years old and had the face of a high school sophomore. As Daugherty set a pick on Price’s man (Chicago’s Sam Vincent), Price Took a dribble, then stopped at the foul line. For a brief second, it appeared price would take a jumper.

But Daugherty was lumbering to the rim. His man (Chicago’s Dave Corzine) had stopped to stare at Price. And Daugherty was wide open. Price delivered a perfect pass.

Daugherty layup . . . two points for Cleveland.

Chicago broadcaster Johnny Kerr was a former NBA center. He raved about Daugherty’s ability to set picks, catch passes on the move, and score with fluid grace, near the rim. “Fundamental basketball,” marveled Kerr.

In this article, published in the April 1991 issue of Basketball Digest, Pluto picks up on Daugherty’s career in its fifth season at the tender age of 25. He’d finish the season averaging 21.6 and 10.9 rebounds per game, his best numbers as a pro by a whisker. But the Cavs wouldn’t make the playoffs, ending the regular-season at a lackluster 33-49.]

****

The life of most NBA centers, especially a fundamental, seemingly plodding player such as the Cleveland Cavaliers’ Brad Daugherty begins like this: He comes out of college as a high draft pick, and the expectations are even higher. When you’re a seven-footer and play a game where the accent is on height, fans naturally expect very big things from the biggest men. He is given a one-year grace period, assuming he shows some promise. Even the most intolerant fans have some patience with rookies.

Then it starts. Why doesn’t he get more rebounds? Why isn’t he more aggressive? Why can’t he block that guard’s shot or keep that midget off the boards? Why doesn’t he make the team better?

It’s the Goliath Syndrome. The point guard is supposed to be the quarterback on the court, the man who controls the offense. But the point guard usually is the smallest player, a Mark Price-type player whose size tends to bring empathy from the fans. A center is supposed to play bigger than life because he seems bigger than life.

Ask Wilt Chamberlain, Tree Rollins, Robert Parish, or Daugherty. They all have stood there and sweated as the finger of blame pointed directly between their eyes after their teams were eliminated from the playoffs. The irony is that as the years pass and the center’s knees begin to creak and his hair turns gray or simply disappears, the fans attitude changes. Frailty makes the big guy more human, and suddenly he becomes the venerable veteran, an old warrior worthy of respect.

Parish is the classic example. At 27, he was booed by the Golden State fans who believed his never-changing facial expression was a sign of indifference. Parish never was a great leaper, a tenacious elbow-swinger or a terrifying dunker, so he was labeled lazy and underachieving on the West Coast. Like Daugherty, Parish was labeled “soft” as a young player.

Ten years later in Boston, Parish was no longer a cigar-store Indian; he had become The Chief. He is stoic and reliable, a guy you can count on because his emotions are under control.

Daugherty appears to be heading down that same path, probably destined to be fully appreciated only when he is nearly gone. “I just can’t let myself worry about that stuff, what people say or write,” Daugherty says. “Just playing the game is hard enough.”

****

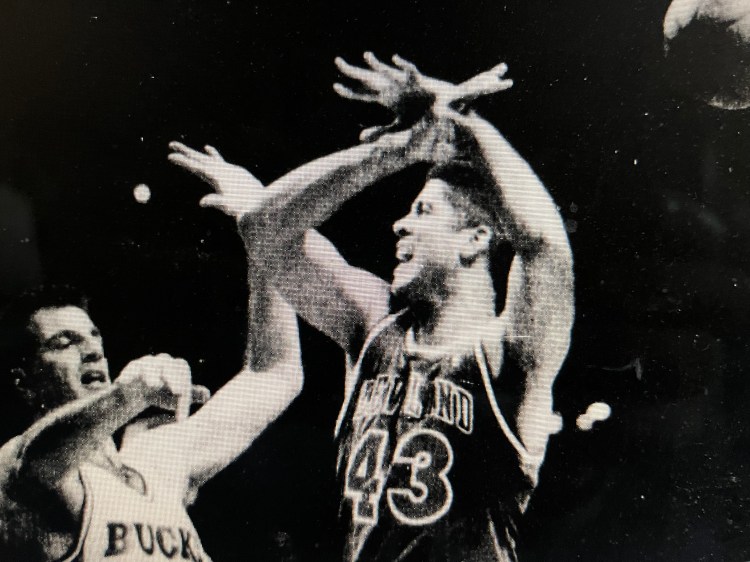

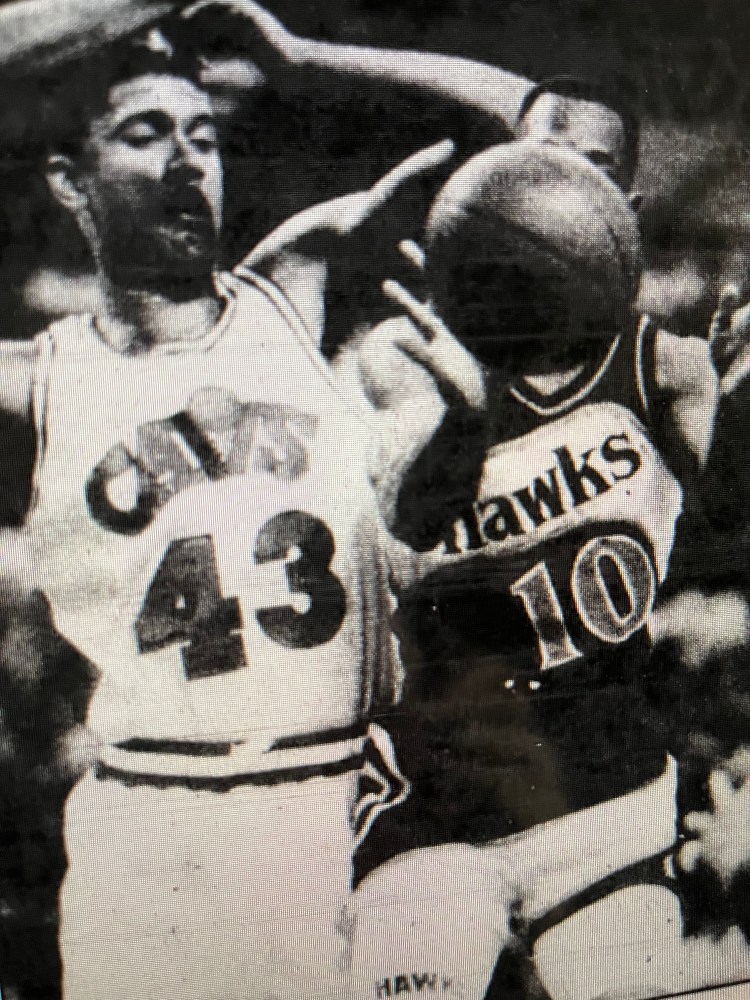

Daugherty was only 20 when the Cavs traded Roy Hinson and paid $800,000 to Philadelphia for his draft rights, a trade that looms as crucial as any ever made in the 20-year history of the Cleveland franchise. Daugherty averaged 16 points and 8.1 rebounds as a rookie while immediately establishing himself as the NBA’s premiere passing big man.

But that is much like being the league’s top rebounding guard—it’s nice, but it’s not really what you are paid to do. At least that is how most fans viewed it.

Most young seven-footers are either too fat or too skinny. It is as if their metabolism is still in a state of flux, not having caught up with all that height. In Daugherty’s case, he was dubbed a soft player in college because some scouts said he wasn’t aggressive enough. His 265-pound frame coated in what was nothing more than baby fat, did nothing to belie those changes.

The Cavs were eliminated in the first round of the 1988 and the 1989 playoffs, series in which Daugherty struggled on the floor and with minor injuries. He bobbled his way through the 1988 playoffs with a plastic cast on his right thumb, which inspired one columnist to ask if Daugherty’s problem was “no thumbs or no heart.”

Somewhere, Parish, Chamberlain, and the rest probably were smiling—not from warm nostalgia, but from memories of similar cheap shots aimed in their directions and from the knowledge that this, too, shall pass.

****

Unlike Patrick Ewing, Hakeem Olajuwon, and David Robinson, there is little about Daugherty’s earthbound game that brings fans out of their seats. His most effective shots are sweet, quick half-hooks or short-range turnaround jumpers. He dunks, but it seems more of an afterthought than a statement.

The thing that’s definitely soft about Daugherty’s game is his shooting touch. But his style is machine-like, almost mechanical. Fake right, go left. Fake left, go right. Most centers fake right, fall down left. Daugherty’s coordination and skills when he has the ball in his hands are truly remarkable.

On defense, Daugherty says, “I’m just not going to block many shots. I try, but I just don’t jump like Hakeem or those guys. I try to work on position, keeping my body between my man and the basket.”

NBA coaches like what they’ve seen in Daugherty. They voted him to the 1988 and 1989 All-Star teams as a reserve. “That was nice,” he says. “But I’m not into that weekend, all the parties and people. I don’t sit up at night wondering if I’m going to make the All-Star team. I’m more concerned about becoming a better player and our team winning. That’s what’s important.”

A lot of players say as much, but Daugherty has demonstrated it in one key area—contract negotiations. He has been with the Cavs for five seasons, and despite being the No. 1 pick, a two-time all-star, and the only seven-footer on the roster, he never has held out, and there never has been a word publicly uttered about him having contract problems. Twice, his contract quietly has been reworked in the summer.

General manager Wayne Embry has praised Daugherty for his understanding of the salary cap and his willingness to fit into the team’s payroll structure. Daugherty is earning about $1.5 million this year, with incentives that reportedly can take him close to $2 million.

“From the moment we drafted Brad, I said that he was an asset to this franchise, not just as a player but as a person,” Embry says. “He wants to be well-paid, and he should be, but he also wants to be a good team player, too. People around here may not fully appreciate it, but Brad is a winner.”

Daugherty says: “A million a year, three million a year? It all sounds so incredible to me. I’m not hung up on making more money than this guy or that guy. I also know that if you give all the money to one or two guys, then the salary cap means you can’t pay everyone else, and you don’t have a good team.”

****

Also, Daugherty not only realized that he has weaknesses as a player, but that they can be corrected. The first is his weight. “I am at 265 now, which is where I usually am,” says Daugherty. “But since I met my wife, I’ve changed my diet around. I don’t eat red meat, and I cut out most junk food. I’ve been lifting and working out in the summer.”

The result? “Brad came to camp in the best condition of his career,” says Cavaliers coach Lenny Wilkens. “He looked sensational.”

Another change is that Daugherty has shown a more aggressive mindset. He once had a tendency to catch the ball and hold it, waiting for a teammate to break to the basket for a return pass, while his teammates stood and stared at Daugherty, waiting for him to shoot the ball. That would bring the offense to a halt while the defense swarmed Daugherty.

Wilkens has been telling Daugherty to be decisive, to catch the ball and immediately make a move, shooting or passing. Daugherty has done just that. In two preseason matchups against the Spurs’ David Robinson, Daugherty averaged 16.5 points and 9.5 rebounds. He piled up 34 points in three quarters against Mark West of Phoenix and had 14 rebounds against Parish in preseason games. By far, Daugherty was the Cavs’ most effective player in training camp.

“Rather than playing pickup games, I spent the summer working on my shooting and my footwork with Joe Wolf at North Carolina,” Daugherty says. “I think it will pay off.”

At 25 and with five years of experience, Daugherty is one of the Cavs’ veterans. “That’s hard to believe,” he says. “I still feel like a kid. I’ve had to tell myself that I have to step forward, that I’m one of the guys on the team that the younger players will be looking at.”

Daugherty is concerned about this season. “I just don’t think we have enough experienced guys to play with the elite teams, such as Detroit,” he says. “Our core is very good, but we don’t have the depth we need. I like the guys we have; I just wish we had more players who have been through some tough situations. We’ll just have to stick together, and the veterans must show a lot of leadership for us to have a good year.”

****

Daugherty missed 42 games because of surgery to remove a neuroma (a tumor made of nerve tissue) from his right foot. “The doctors told me the operation should be no big deal, that I shouldn’t miss any games,” Daugherty says. “But they did say there was a 1-in-20 chance that a serious infection could form. The odds sounded good, so I had the operation and I ended up missing half the season.”

When Daugherty did return, he was in first gear while the rest of the NBA was playing pedal-to-the-metal midseason basketball. He was stiff, rusty, and often frustrated. “Even though I was playing, I couldn’t move like I used to,” he says.

By the end of the season, Daugherty began to be a major factor. He averaged 22 points in the playoffs, partly because the Cavs’ outside shooting improved to the point where he didn’t see as many double- and triple-teaming defenses. But there also was a change in Daugherty—he played with more confidence and authority.

“When I was hurt, I did a lot of jokes about sitting there in that hotel room, watching Andy Griffith,” Daugherty says. “But I also had time to think. I found myself missing the game so much. Never before had I stopped playing basketball for that long, and it was only then that I realized how much I loved it.

“I came into the NBA thinking I’d play eight to 10 years, make some money, and then go home to North Carolina. I liked the game, but I didn’t love it the way I do now. I think that will help me to be even a better player because I want to make the most out of what I have.”