[John Brisker remains the ABA’s all-time favorite tough guy, the one that everyone loves to talk about even today. But Warren Armstrong, later Jabali, deserves a high honorable mention. In fact, he got that high honorable mention in Terry Pluto’s classic ABA oral history, Loose Balls. Steve Jones, the late ABA and broadcasting great, waxed on to Pluto about his enigmatic former teammat. Jones said in part:

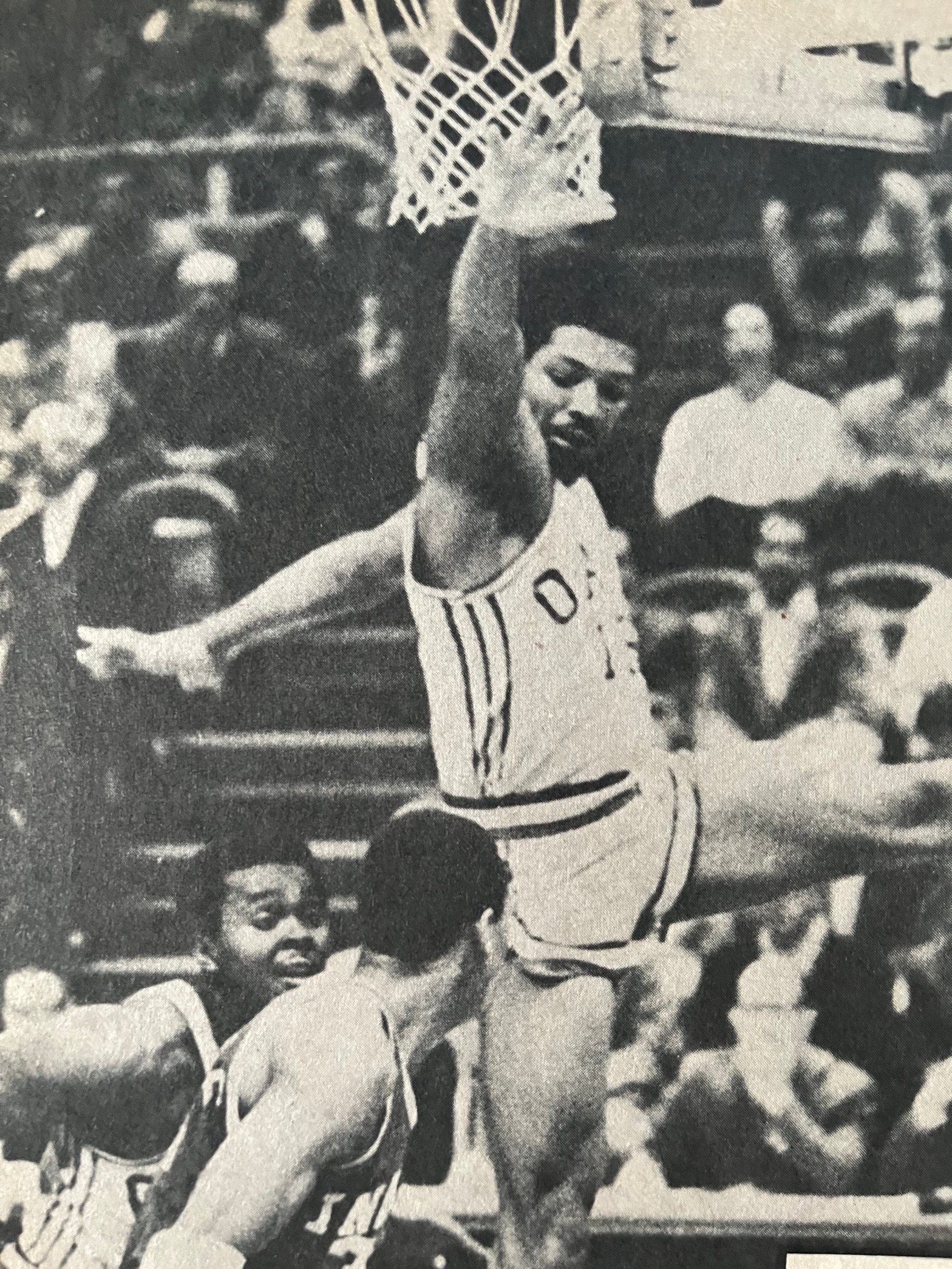

In his first year with Oakland, Jabali was Warren Armstrong, because he hadn’t become a Muslim yet and changed his last name. There was this great picture of him flying through the air—they called him Batman. Warren played a physically intimidating game. He’d drive on you to the basket, dunk it, then catch the ball and throw it into your face. He looked strong enough so that most people wouldn’t mess with him either.

This guy was a player. He could rebound in traffic with guys 6-foot-9. He could push the ball up the court like a guard, and he was absolutely fearless going to the basket. People never appreciated Warren for the kind of player he was because of his politics and the things that happened around him. Remember that this was when black awareness was coming to the forefront—1969, 1970. Warren wanted a little or nothing to do with anything that was white. If someone was in an accommodating state of mind toward the establishment, you always got an argument, and a strong one, from Warren.

To add some belated detail to Jones’ memory, I’ve pulled together some telling clips on Jabali’s seven-year ABA career. Let’s start with a short clip from his rookie season with the Oakland Oaks. The clip comes from the Oakland Tribune on April 9, 1969, and telling the tale is staff writer Dave Newhouse.

But first, one more thing. Jabali died at age 65 from heart failure. That was back in 2012. The following year, his autobiography Thanks to You was published post-humorously. If you want to know more about Jabali in his own words, that’s your ticket.]

****

Warren Armstrong played basketball last night the way Dr. Naismith must have intended it as the Oakland Oaks gained the upper hand again in the ABA Western Division playoffs. In a game more bruising than even Sunday’s in Oakland, the Oaks bounced Denver, 121-99, to take a 2-1 lead.

Elbows, punches, and verbal exchanges flew on both sides, and the crowd of 5,062 rained the court with cups full of ice, rock-like projectiles, and coins. The only hurt Oak wasn’t even a player—Ken Davidson, chairman of the board. A flying nickel hit Davidson, sitting at press row along courtside, in the left eye, cutting the skin between the eye and the top of his nose and leaving an ugly, purple welt.

If the extracurricular activities had lasted for four quarters, which they didn’t, they couldn’t have diminished the performance of rookie Armstrong, who, in a word, was awesome. Young Warren scored a pro-high 42 points (his previous best was 38) and plucked a game-high 15 rebounds. That’s for starters.

“Give one guy credit, Warren Armstrong,” said Denver coach Bob Bass. “He blocked shots, passed, made steals, rebounded, shot inside and out—what else is there to do in the game of basketball?”

The Wichita State phenom had 21 points by halftime, as the Oaks broke a 33-33 tie after one quarter to lead, 71-49. Denver had four field goals in the second quarter and had been humiliated on the boards at the halfway point, 39-17. The Rockets never drew closer than 15 points thereafter, as they lost the precious homecourt advantage they were seeking . . .

Nothing happened between Sunday’s combatants, Oakland’s John Clawson and Denver’s Larry Jones, who had 28 points last night, but only six after intermission. Armstrong played a part in this, too.

Jones and Larry Brown did get into a brief spat—a no-punch skirmish—in the first quarter, but were quickly pulled apart. Ira Harge and Denver’s Byron Beck made it more interesting about a minute later. Harge came off with a rebound, and on the outlet pass, somehow caught Beck in the beezer. Beck went after Ira, and they were swinging before Armstrong grabbed Beck around the neck from behind and dragged him away. Beck’s 6-9 and 230, while Warren’s 6-2 and 205.

Harge and Beck were cordial to each other later in the game, even smiling, and Bass stated that Harge’s action wasn’t deliberate. But Bass had more to say about Alex Hannum.

“Alex made the statement that what happened Sunday between Jones and Clawson was the worst thing he’s seen in 19 years of basketball,” Bass declared. “I’m not going to make other statements he made either, like the next game (last night’s) will be rough and aggressive.

“Whenever guys get hit, shoved, elbowed in the face, intentional or not, what can you expect them to do but retaliate? The fracas tonight had nothing to do with the outcome. There was just no movement in our game. But if they come to swing on us—and I’m not saying they are—we’ll swing back.”

The Denver fans seemingly come to boo Hannum, not to watch the game itself. And Alex doesn’t let them down, jumping and stomping, yelling at the officials and the Denver players, and going through numerous histrionics.

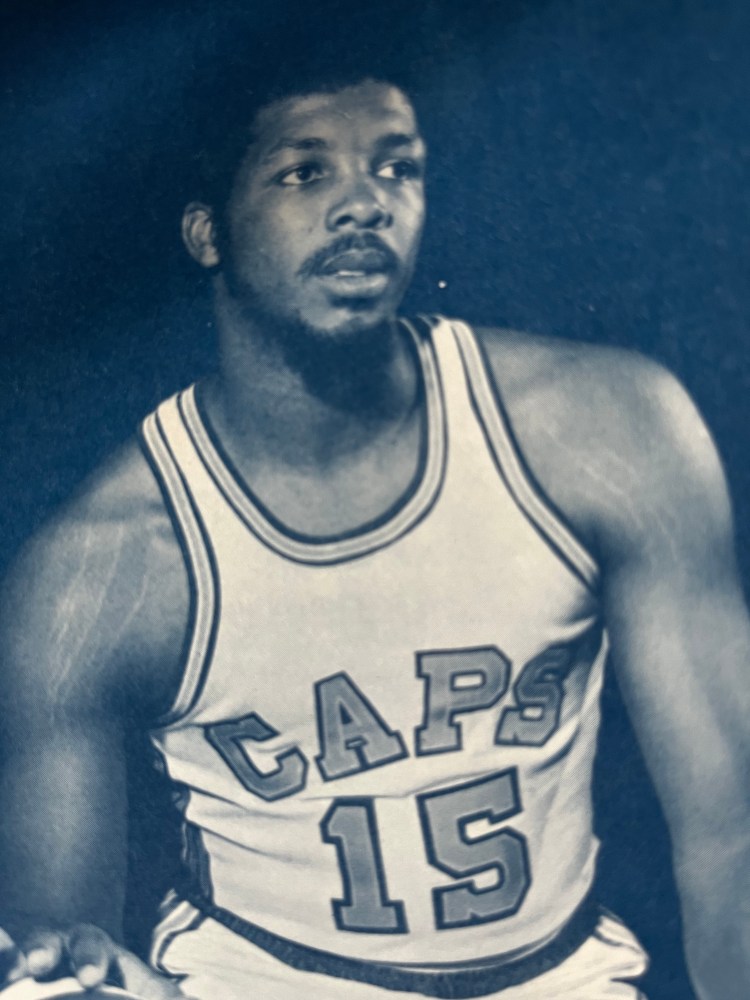

[The Oakland Oaks landed the next season in Washington, D.C. and morphed into the Caps. Armstrong (Jabali) tagged along with the team, but a rash of injuries interrupted his sophomore season. Nevertheless, when healthy, he continued to impress, routinely outrebounding his taller opponents. Take this brief write-up from November 7, 1969. It comes from Bob Whitney, a reporter with the Washington Daily News.]

Under ideal circumstances, Warren Armstrong would play at a guard position for almost any team in professional basketball. For the Washington Caps, defending champions of the American Basketball Association, the circumstance is not ideal.

It would seem to be a sad comment on the state of things around the league that Warren Armstrong, all 6-foot-2 of him, could fill in at forward and beat most of the big man around the ABA at their own thing. “It isn’t,” Washington Caps coach Al Bianchi said yesterday as the Caps worked out at the Andrews, Air Force Base gym.

Armstrong is easily the smallest forward in either professional basketball league. Yet after 11 games, he has 112 rebounds for a 10.2 average, second best average on the team. Only center Ira Harge has more. Harge is 6-foot-9.

“Size, and I mean height, does not always make a difference in rebounding,” Bianchi said. “Rebounding is timing, knowing where to go and being there. Some players have a knack for getting to the ball.”

Only once in recent pro basketball history has a guard, or in Armstrong’s case, the equivalent of a guard, led a major pro team in rebounding. That was Jerry Sloan of the NBA’s 1967-68 Chicago Bulls . . .

With a not-so-sound knee this season, Armstrong has played poorly at times. He was benched on the last road trip. But in the opening game on October 18, Armstrong did his thing—gimp-kneed and overweight.

“There is no way to stop a team with people like that,” New Orleans coach Babe McCarthy said after Armstrong made 6-foot-7 Jim Moreland look especially bad. “Here’s a guy who stand 6-foot-7,” McCarthey said. “He gets position for the rebound, and Armstrong, who is 6-foot-2, goes in over top and takes the ball.”

There must be and is a plausible explanation for Warren Armstrong. “You’re not talking about somebody that’s 6-foot-2,” Bianchi said. “You talk about what a man plays like. [The Caps] Henry Logan is six-foot. He’s physical, and he’ll challenge a bigger man. He plays like he’s a 6-foot-2 or 6-foot-3 guard.

“Warren plays like he was 6-foot-6 or 6-foot-7. It’s not all jumping ability, either. He can jump with anybody, but [when] he gets around the ball, he’s got timing and he’s strong. When I was playing with Philadelphia, Dolph Schayes was like that. Dolph was 6-foot-8, but he couldn’t jump high off the floor,” Bianchi said, holding his hands about six inches apart.

“Dolph couldn’t even dunk a basketball, yet every year, he led the team in rebounds.”

[Before his third ABA season, Armstrong (Jabali) was traded to the Kentucky Colonels. He arrived in Louisville heralded as a premier ABA talent, the “meanest man in basketball,” and, still only whispered, a real flake. His propensity for the latter promptly irritated the Kentucky front office. In fact, as this article from the Louisville Courier-Journal documents on October 10, 1970, so irritated did Kentucky general manager Mike Storen become with his new flake-in-residence, he suspended Armstrong indefinitely before the regular-season even started. Storen, a former Marine who liked to do things his way, soon traded Armstrong to the Indiana Pacers. At the typewriter is the Courier-Journal’s Dick Beardsley.]

Warren Armstrong, expected to be a starting guard for the Kentucky Colonels, was suspended yesterday, just five days before the start of the American Basketball Association regular-season. Though termed an indefinite suspension without pay, Colonels president Mike Storen listed Armstrong’s chances of ever playing for the Colonels again at “zero percent.”

Armstrong was suspended because of a “series of disciplinary problems . . . actions detrimental to the best interest of the team,” according to Storen. He refused to disclose specific problems or actions, saying, “There would be no advantage in doing that.”

The Colonels acquired Armstrong from the Washington Caps (now the Virginia Squires) during the offseason for next year’s No. 1 draft choice and a player still to be named. He came with glowing credentials—a 22.8 scoring average last season and the league’s Rookie of the Year award for the 1968-69 season.

He also came with a history of causing trouble. “I’ve talked with him at great length,” said Storen of the month that Armstrong was with the Colonels. “That’s one of the problems. I’d say we’ve had good communications. But it has to manifest itself in action. And that hasn’t happened.

“We as a team, as a unit, as a franchise, can’t live with the flip-flop. You never know when he’s gonna say, ‘I don’t want to ride the team bus,’ or one of 88 million other things, or ‘I don’t like that particular jersey. I want a different one.’ And you just can’t operate that way.

“Everyone has to know why there are rules and what they are, and that there are consequences if you don’t follow them. Now, if a guy wants to take it to these extremes to find that out, fine. But I’d say it was probably one step too far. Now the next guy will believe us, maybe, when we explain what we mean by cooperation.”

Storen was hesitant to say that Armstrong’s attitude might have affected the Colonels’ play on the floor. “To some degree, you think it does,” he said. “But how do you equate that against 20 points a game? I don’t know. I don’t think you can really put your finger on it.”

Two Colonel veterans, Louie Dampier and Jim (Goose) Ligon, said that Armstrong would on occasion play a slower game than the running game that the Colonels play most often. “He played a different style,” said Ligon. “He’s not slow, but he just seemed to like to take things a little easy.”

Both Dampier and Ligon said they each “personally” got along with Armstrong. “But some of the players were kind of what you might call afraid of him,” Ligon added. “They didn’t try to get to know him. They seem to be going on his past reputation. He was the kind to keep to himself. He didn’t socialize, or do some of those other things; but he doesn’t have to do those things if he doesn’t want to.”

Concluded Storen:

“He (Armstrong) has to decide what it is [that] he wants out of basketball. He can be a super athlete. The only thing that keeps him from building on the leadership potential he has is a decision in his own mind. Does he want to be a negative influence or a great player?”

[After just one fairly lackluster season (1970-71) with the Indiana Pacers, Armstrong got moved again. He joined the Miami Floridians for the 1971-72 season, still debatably reputed to be the “meanest man in pro basketball.” He also now publicly answered to the Muslim last name, Jabali,” meaning “The Rock.” Playing for the Floridians, Jabali was very much The Rock. He appeared in all 81 games, averaging nearly 20 points, 8 rebounds, and 40 minutes per outing.

The ill-fated Floridians folded after the 1972 season, and as part of the league’s dispersal draft, Jabali continued his ABA career in Denver. There, he was reunited with Alex Hannum, his coach in Oakland during his rookie season. But, as this article (no byline) details in the Winston-Salem (NC) Journal on February 15, 1973, The Rock wasn’t unbreakable.

Alex Hannum, who should know, uses this example of how great Warren Armstrong was in 1968-69 when he was Rookie of the Year in the NBA. “He’d get up in the air, and he didn’t know which hand to dunk with—he could dunk with both—but he always made the right decision before he came down.”

There have been plenty of changes—a new name, knee surgery, three new teams—since that time for the former Wichita State All-American, who now calls himself Warren Jabali. But Hannum still is the one best qualified to describe Jabali, the Most Valuable Player in the ABA All-Star game. Hannum coached him that first season with Oakland and coaches him now with the Denver Rockets.

“Now he has to warm up just to dunk at all,” Hannum says.

But the operation on his right knee that forces Jabali to play in pain has not made him any less a ballplayer in the eyes of Hannum and the other followers of the ABA. If anything, he might be even more productive than in his first year and a half, when he averaged about 22 points and 10 rebounds a game before entering the knee.

“He is a more rounded player now, more savvy,” Hannum says. “He has a great feel for what is happening on the court. He is certainly one of the best playmakers and clutch players I’ve ever coached.”

Jabali was also selected to the All-Star team for the third time this season and went on to win the MVP award in the classic last Tuesday, as he led the West to a 123-111 victory at Salt Lake City.

After a brief fling with Indiana, he averaged 19.9 points, 8.1 rebounds, and 6.1 assists a game last season with the Floridians before coming to Denver in the dispersal draft. This year, he has taken over as quarterback in Denver, along with being the Rockets’ man in the clutch, the man who gets the ball in the final quarter when the game is on the line. He usually comes through with the big play.

He ranks 21st in the league in scoring with a 17.3 average. He ranks ninth in three-point field goal shooting at 26.4 percent; he ranks eighth in free-throw shooting at 81.5 percent; he ranks fourth in assists with 6.7 a game; and he ranks fifth in steals with 134.

Jabali likes it better this way, although he still remembers how it used to be as a high-powered scorer and rebounder. “I exploded much more on the court in those days,” says the muscular guard in his quiet way. “But it hasn’t been that much of an adjustment since the knee injury. High jumping is just spectacular. Rebounding is a timing thing. I can get just as many rebounds now without jumping as high.”

Playmaking is nothing new to Jabali either. He held the career assist record, along with the rebound mark at Wichita State as a 6-2 forward. “I still controlled the ball then as a forward,” he says, “but now I run the whole offense from the backcourt. I like it better this way. It’s a growth thing, and I think I’ve done a lot of growing since those first seasons in the ABA.”

[Finally, let’s jump ahead one year to the February 20, 1974 issue of Basketball Weekly. Dave Overpeck, the knowledgeable ABA scribe from Indianapolis, published his weekly column titled, “The Warren Jabali Case.”]

You knew Alex Hannum wanted to be rid of Warren Jabali. The trade rumors had been in the wind since mid-December. Still, it came as a surprise. You just don’t put the first team all-league guard on waivers. Not one who leads the ABA in assists. Not one who is scoring 16 points a game, not one who stands fifth in the league in three-pointers, not one who is in the top 10 in steals.

Sure, you may trade away a starter in the All-Star game—even two games after that showcase. But you don’t put him on the waiver list, you don’t put him on the counter where anybody can pick him up for the pocket-change $500 waiver price.

Only Alex Hannum couldn’t get anything for Warren Jabali. Nothing. Despite all those glowing credentials, nobody wanted this player of proven outstanding capabilities. And, in the end, Hannum and the Denver Rockets wanted him less than anybody. For on February 1, Jabali did go on the waiver list—an all-star among the Jerry Chambers and Billy James and Joe Reeves.

And like the Chambers, the James, and the Reeves, he went unclaimed. From late Friday afternoon until late Tuesday afternoon, he sat there on the counter, marked down to $500. And nobody claimed him. Nobody wanted an All-ABA guard, the MVP of the 1973 All-Star game, the top playmaker in the league. He cleared waivers. He was released. A free agent.

From the bare statistics, without knowing anything else, you almost had to presume nobody in the other ABA cities was watching the Telex—or reading the papers. But it really wasn’t that great a surprise that Jabali went unclaimed. A bigger surprise would have been somebody grabbing him up.

Warren Jabali is Black, militantly so. When he won a trip to Europe for being the All-Star MVP, he wanted to be sent to Africa instead. That alteration was made—but not without ill-feeling. He sees the world in two unshaded colors. He is devoted to one, at war with the other.

Despite his multitude of talents—which were truly awesome before a variety of injuries and ailments robbed him of much of his speed and quickness, it has been his outlook on life that has gained him his greatest reputation in the ABA. The label reads “trouble.” A bad actor. A source of dissension. A public relations blemish.

In six ABA seasons, Denver was Jabali’s fifth stop. He had played longer and better with Alex Hannum than for any other coach. You could almost hear the wheels turning: if Alex is so fed up with him that he would put him on waivers, why do I need his kind of trouble?

So Jabali was not claimed.

But, according to Hannum, Jabali did not go on waivers because he was creating problems or making his race consciousness obtrusive. His strong, thoroughly independent personality was not viewed as a debilitating force to the Rockets. But, said Hannum, “Warren Jabali is such a strong, dominating player that he takes complete control of the game. He plays the game a certain way, and when he’s on the floor, you simply have to play the game his way.

“We finally came to the decision that his style wasn’t the best for what we were trying to achieve. So we were faced with riding out the rest of the season that way or doing something now to see if our young players can perform in the way we want to go or whether we have to draft in that direction.

“We couldn’t do the latter with Jabali here. Frank Goldberg (who, with Bud Fischer, are primary owners of the Rockets) and I were together almost all week. We talked about it, and finally decided this is what we had to do. There were no off-court problems at all with Warren. We just thought this was something we had to do for the betterment of our club.”

Opinion on the move was mixed. Quite obviously, some of the Rockets were happy to see Jabali gone. Some fans just as obviously weren’t—they booed Hannum when he was introduced before the next home games. First returns on the floor were mixed. In their initial outing without Jabali, the Rockets clubbed Virginia, a bad road team, 138-120. But the next night, his floor leadership was clearly missing as Denver fell, 111-102, to Indiana, another poor road club.

Probably, the Pacers’ George McGinnis summed up the majority ABA opinion when he said, “I don’t care what anybody says, the Denver Rockets are not as good a club without Warren Jabali.”

[After clearing waivers, Jabali moved to Tanzania as an advisor for the nation’s new basketball program. By early November 1974, already nine games into the regular-season, the San Diego Conquistadors signed the now 28-year-old Jabali. After ironing out a few passport problems, Jabali returned to the U.S. and joined the Conquistadors. “He has a cut contract, and so I’m not worried about anything,” said his new coach Alex Groza. “If he is not going to help us, we can waive him again.” Jabali, claiming his sojourn in Africa had cured his quick temper, caused little, or no, trouble on the court and earned kudos for his play, just not his politics, in his final ABA season. He averaged 12 points, 4 rebounds, and 30 minutes a game.]