[At the conclusion of my previous post on Warren Jabali, he’d wrapped up the 1975-76 season playing for San Diego in his seventh ABA campaign. San Diego desperately needed a heavy infusion of cash to hang on for one more season, and it didn’t look good. Bummer, as everyone said back then, but Jabali wasn’t exactly bummed. He was ready to retire. His knees ached from seven ABA seasons, and he wanted to embark upon a new life in Africa. But before hanging up his sneakers, Jabali sat down for a long interview with the Los Angeles Times, during which he explained that his recent first trip to Africa had changed him for the better:

“All the anger I had in me doesn’t affect me the same way now. I realize emotional outbursts aren’t going to change anything. I recognize the need to be disciplined, and that social change comes more easily through successful endeavors, not upheaval. The militancy, if you call it that, was meant as an expression of anger at past and continuing injustices. Those feelings haven’t changed, but my methods of expressing them have.

By the 1990s, Jabali’s new life in Africa had come to naught. He had settled down in Miami, where he once played for the ABA Floridians, and now spent his days with a whistle around his neck. He was a somber-faced physical education teacher at an elementary school in Miami’s hardscrabble Carol City.

On September 17, 1995, the Miami Herald ran the following story from reporter Gregg Doyel, who caught up with an older and wiser Warren Jabali. The former meanest man in the ABA, the one who once infamously stomped on the head of an ABA opponent, was now all about helping kids and doing the right thing.]

****

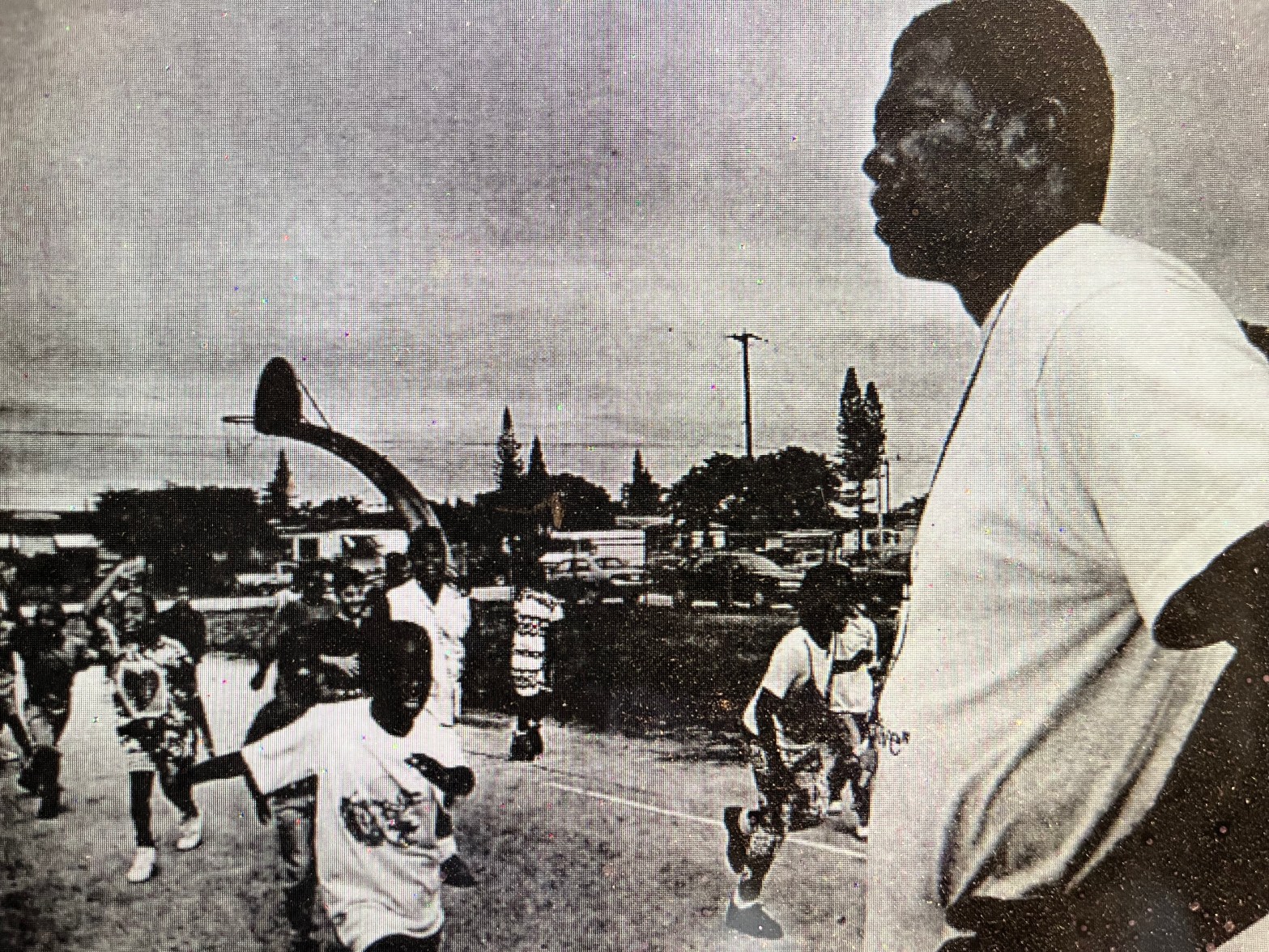

It’s a hot, muggy afternoon in the gut of Carol City, the kind of afternoon this neighborhood of barred windows and broken-down cars seems to get. School is out at North Dade Elementary. A boy scurries into the street but is stopped halfway by a booming voice that bores a hole through the humidity.

“Where are you going?” The voice sounds like an old Buick missing a muffler. “Get back here and find a crosswalk!”

Warren Jabali, 49, the somber face that comes with the huge voice, leans against a nearby fence as the boy scrambles back. This is vintage Jabali: trying to steer another kid in the right direction.

Jabali is a physical education teacher at North Dade. People who have crossed his path in the last 30 years have known him as more: professional basketball player, hero, villain.

He is also a commissioner of Overtown’s Midnight Basketball League, which uses hoops as leverage in the lives of men ages 17 to 30. They play four nights a week, from 8 to midnight at Booker T. Washington Middle School, and get counseling and tutoring. Players make strides off the court—or they don’t get back on it. As commissioner, Jabali counsels men who have made mistakes. He breaks up fights. “I keep the lid on,” he said.

“Warren doesn’t have to do this,” said Miami attorney Deborah Mayo, a league director. “He is the one man who has held the league together. Warren Jabali is my hero.”

****

He wasn’t born a social activist. Warren Jabali wasn’t even born Warren Jabali.

Warren Armstrong was born 49 years ago to a Kansas City, Mo. steel worker and housewife, the first of 11 children. One brother became an alcoholic, another a drug addict. Armstrong avoided those potholes, using basketball to get a scholarship to Wichita State University. He is WSU’s No. 12 all-time scorer with 1,301 points from 1965-68.

“Warren was one of the more talented players of his generation,” WSU teammate Ron Mendell said. “He had the body of a fullback but almost literally could jump and touch the top of the backboard.”

Because of basketball, Armstrong saw the 1960s through the eyes of a student. America was changing with every campus protest, and he attended many—at schools where WSU was playing that night. Then he began changing, Mendell said. “He was very nice, a terrific guy the first time I met him,” said Mendell. “When he came back to school one year, he had changed. He was indifferent, aloof, restrained—angry at everything.”

Jabali doesn’t remember whether he was a freshman or sophomore, but he figures his life changed the day he heard Malcolm X. “In his analysis, Black people were captured and brought to this country as slaves, and later took the names of their masters,” he said. “The first step in my evolution was realizing my identity.”

Warren Armstrong became Warren Jabali in 1969, his second year with the Oakland Oaks of the American Basketball Association. Jabali—Swahili for “The Rock”—once dunked against Kentucky and came down with the rim in his hand.

“People viewed him as hostile,” said Hal Blitman, coach of the ABA’s Miami Floridians. “I don’t think he was hostile against all whites. He was hostile against what was happening to African Americans. We spent a lot of time talking about it.”

They would have another conversation, years later, that would send Jabali’s life in another direction.

****

Mayo might now call Jabali “my hero,” but men who knew him in the ABA had a slightly different opinion. Jabali was one of the league’s popular players, according to Loose Balls, Ohio sports writer Terry Pluto’s 1990 book about the ABA seen through the eyes of former players and coaches. In a chapter titled “The Meanest Men in the ABA,” two were singled out—one was Jabali.

Said opponent Mel Daniels: “Jabali was as mean a guy as there was in the league.” Added foe Dave Twardzik: “The whole league hated Jabali.” Said teammate Dan Issel: “Our whole team was scared to death of the guy, because he was so mean.”

Mean? Maybe. Opinionated? Definitely.

After winning the 1972 ABA All-Star Game’s MVP award and the accompanying free airline ticket to anywhere in Europe, Jabali said: “I want to go to Africa. If they won’t send me to Africa, I want the money instead of the ticket.”

Al Bianchi, who coached Jabali briefly in Washington, said: “I never really knew what was going on in his head, but I didn’t care, either . . . the man played.”

Jabali believes politics got him kicked out of the ABA. During the 1974 All-Star weekend, players were housed in what they felt was a substandard hotel while the league’s owners stayed in a plush resort. Rankled, they voted to boycott a meet-the-public luncheon.

Word got around: Jabali organized the boycott. “It was my idea,” Jabali said and unleashes a rare, throaty laugh. “It wasn’t like I organized it, though. I merely suggested an idea. But, ‘It was Jabali’s fault.’”

Jabali was released by Denver—the next day. Although he was averaging 16 points and a league-best 7 assists at the time, not one team in the ABA would spend the $500 waiver fee to add him to their roster.

“Can you name one other athlete,” he said, “who was selected to start in an all-star game and then the next day was released.”

****

Jabali talks about preferring to mingle with African-Americans only—yet lives in a mostly white apartment complex in southwest Broward County. He was moved by the Muslim movement to change his name—but stayed a Christian.

“I’m a pragmatist,” he said. “There’s only one house in this neighborhood I want to live in, and it was built by a drug dealer. So I live in Pembroke Pines. I do what I have to do.”

In 1979, social activist Warren Jabali donned a coat and tie and entered an executive training program at a Miami department store. One customer recognized him. “I never thought I’d see Warren in a suit,” Blitman said. “I was principal at Nautilus Junior High at the time, and I talked him into working as a P.E. teacher. It wasn’t hard. I think he always had a drive to help kids who were at risk.”

Jabali has taught for 15 years. He wants to run interference for the next generation, but knows it won’t be easy. In North Dade’s fourth-grade alternative education program, for example, the number of students who live with foster parents is twice that of students living with her mother and father.

On this day at North Dade, Jabali slides through the milling children as they head home. A little girl holding a pickle. Gives him a hug and moves on.

“You see her? She is what you call an at-risk fourth-grader. Have you ever seen an ‘at-risk’ fourth-grader? That’s a scary concept,” Jabali said. The girl, he says, lives with her grandmother, because her mom is a crack addict.

“That’s the kind of kid we need to reach. Unfortunately, that’s the kind of kid this society is producing at an alarming rate.”

I felt he lost his militancy attitude due to the fact of his fear of water. Coaches and owners like to control folks like a caged animal.

LikeLike