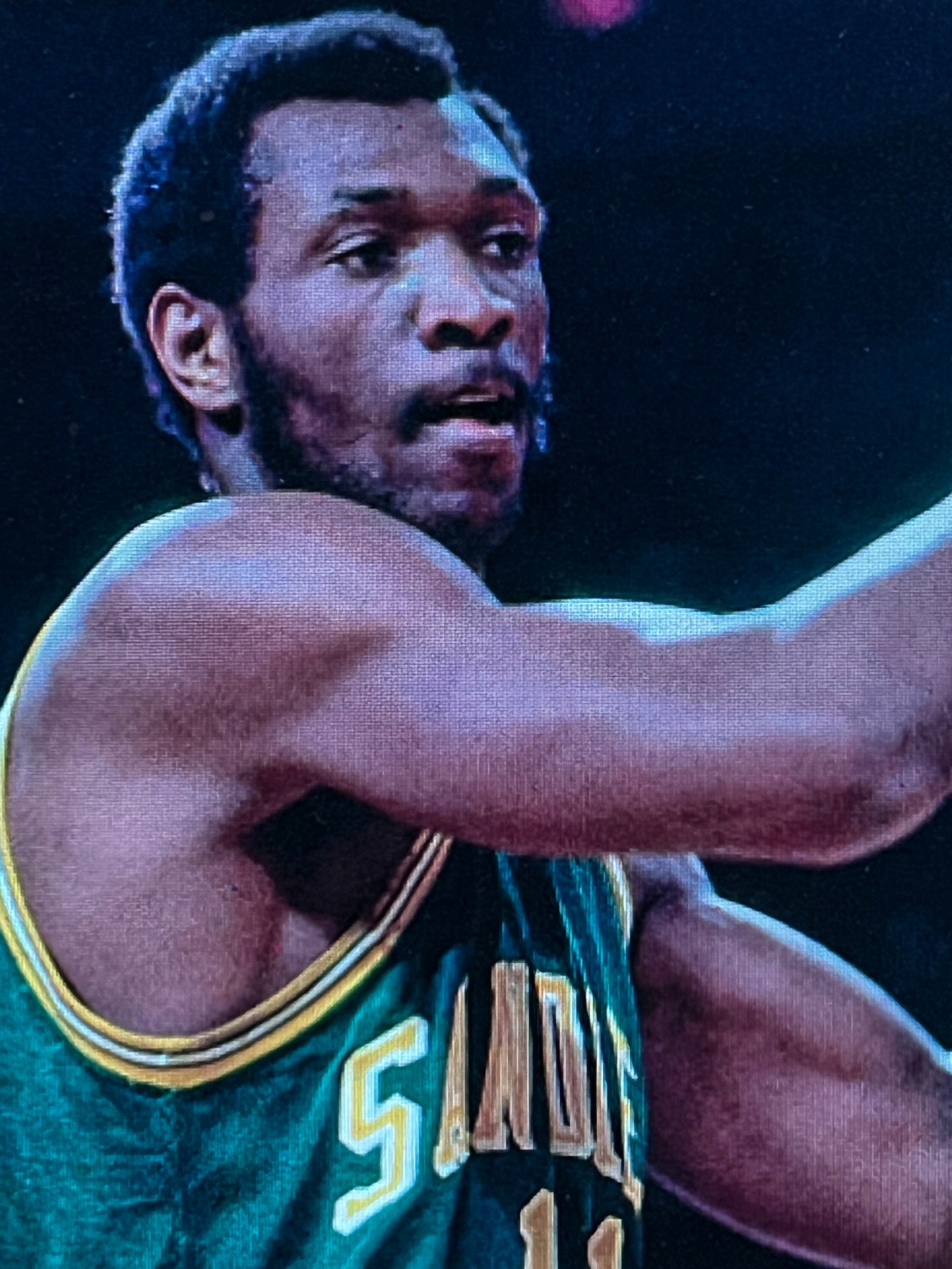

[Yes, 1971 was a new year for Elvin Hayes. Too bad that after this article published, 1971 turned out to be more of the same for Hayes. He shined again individually throughout the season (28.7 points and 16.6 rebounds per game), but his San Diego Rockets continued to fizzle on the floor and in the divisional standings. In 1971, most NBA analysts continued to finger Hayes for the fizzle, calling him a ball hog, a flawed big man, and a lot of other more personal snipes and epithets.

Even though 1971 wasn’t especially kind to Hayes, I think the better headline for this story would have been the broader: In Defense of Elvin Hayes. For that’s what this story is all about. Defending Elvin Hayes in general.

Merv Harris, a fantastic sportswriter with the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner who covered the Lakers, steps forward here to defend Hayes from his growing number of detractors. Harris starts the story with a bullet list of items in defense of Hayes that, in my eyes, doesn’t really work as a lead. It’s got formatting issues. That aside, Harris raises many valid points and opens a more thoughtful window into Hayes’ early pro career. Harris’ defense appeared in the March 1971 issue of magazine All Sports. Enjoy.]

****

ITEM: In two years as a professional, he’s been the National Basketball Association’s leading and then fourth highest scorer, as well as the fourth highest and then leading rebounder.

ITEM: In two years as a professional, he twice has been starting center for his division in the annual NBA All-Star Game. As a rookie, he earned the assignment away from Wilt Chamberlain. The next season, he was the leading scorer in the game.

ITEM: In two years as a professional, he’s been the most durable athlete in the league. He has yet to miss a game. Twice, he has led the league in total minutes played.

ITEM: When he won the scoring championship in his first season in the NBA, he became the first rookie since Wilt Chamberlain to win the title.

ITEM: Before coming to the pros, he set NCAA career and/or single season records for total field goals, total points, and then several other vital categories. That some of these marks have since been broken (mostly by Pete Maravich) doesn’t dim the fact that he accomplished more in these statistical categories than any of the hundreds of thousands of collegians who came before him.

ITEM: Before coming to the pros, he scored 39 points and added 15 rebounds to lead his university to a victory over Alcindor and UCLA, which ended a 47-game Bruin winning streak and which was watched by the largest crowd—more than 50,000—ever to see a basketball game.

And, finally . . .

ITEM: Elvin Hayes, despite all these glittering accomplishments, failed to get as much as a single third-place vote last season in balloting among his fellow pros for Most Valuable Player after leading the San Diego Rockets in 10 of 12 offensive categories. Ask the average fan to name the superstars of the game, and he’d get few mentions, even in San Diego, where he is the primary hope of the Rockets to establish themselves as a successful franchise. He’s easily the most underrated center in the league. He’s all too aware of these things, permits them to gnaw and burn at him. And he thus makes it even more difficult for himself to earn the acclaim his achievements would seem to have earned.

So . . .

“What’s wrong?” Elvin Hayes asks painfully, tolling off some of his accomplishments in a uniquely earnest way of his which easily could be interpreted as bravado or bluster, but which, in truth, is a product of a boyhood and young manhood spent tirelessly to escape the suffocating poverty and obscurity of the Black, rural deep South.

When Elvin Hayes talks about himself, he speaks in superlatives, it’s true, and he can recite awards and statistics at the drop of a rebound. And he’s often—far too often—spoken indiscreetly in bitter criticism of those who have given honors to other players that he felt should have gone to him.

He flits always with that fine line between exaggerated ego and an element of earnest de- personalization. The pronouns may be “I” and “me” and “mine,” but behind them seems to be a third-person element which softens the surface egotism. He seems to ask not for recognition personally, but for what he’s done on the court, almost as if the points and rebounds and blocked shots composed a separate personality all their own. He is saying, in effect, “These are things I worked hard to achieve. I ask not homage for native talent, but for recognition of the effort expended to reach this plateau.”

Of course, he might not say it with quite that much rhetorical flourish. At age eight, he was out in the cotton fields around Rayville, La., adding to a large family’s meager income. Within a couple of years, he was working from four in the morning until noon, without a break, at $4 or $5 a day.

Then he would go to school in the ramshackle, primitive facilities of Dixie. That was followed by hours of shooting a stuffed sock or some other makeshift missile through a scrap metal, improvised hoop tacked to a pole or a tree on a dusty, dirt farmyard, until he’d grown enough, gotten skilled enough, to have access to a real basketball and regulation hoop.

That kind of boyhood, isolated and insecure, is not the environment that produces orators. But it can produce families with determination to reach out and do better, such as the Hayes family, and it can shape an Elvin Hayes—ambitious, distrustful at first of white faces, cautious to avoid being ridiculed, capable of moods ranging from boyish revelry to cursing and rage.

****

The transition from Eula Britton High School to the University of Houston, and then to conservative WASPish San Diego hasn’t been an easy one. These things have contributed to Elvin Hayes’ low public esteem, despite his obvious athletic skills and his initial three-year, $308,000 contract (which later was torn up in favor of an even richer deal).

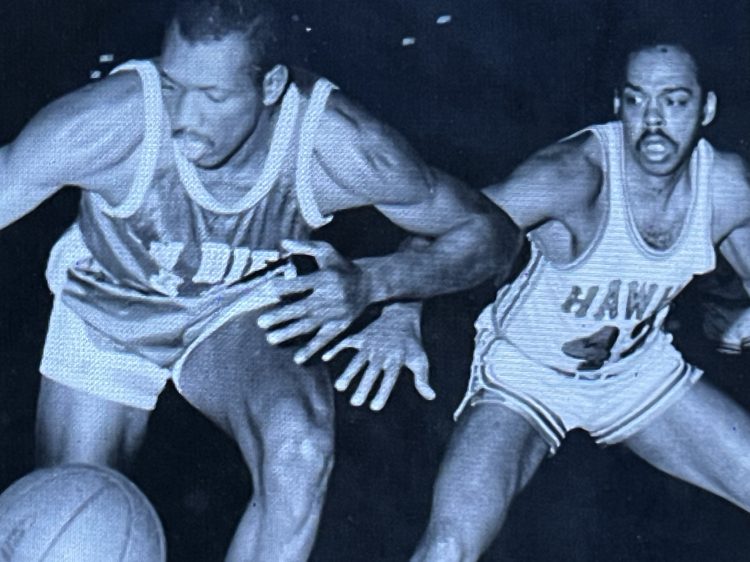

From his first days as a pro, however, lack of faith in himself as a player has not been his handicap. His second exhibition game as the No. 1 draft choice of the Rockets (first player selected by any NBA team that year), the 6-9 Hayes was matched against the smooth, versatile, universally liked Nate Thurmond of the San Francisco Warriors in front of Nate’s own fans at the Cow Palace. It was to be a first barometer of his pro potential following a collegiate career which had ended on a bitter note when Alcindor and UCLA thrashed Houston in a much-heralded “rematch” for the NCAA championship. Could Hayes play effectively at center against so skillful a proven pro as Thurmond.

The next morning, I sought out the rookie to hear his reaction to the experience. “Tell me, Elvin,” I asked, “how was it to play against Nate for the first time?”

The rookie paused to consider an answer. “How many points I get?” he asked finally.

“Eleven,” I told him, puzzled.

“How many points Nate get?” Hayes continued.

“Twelve,”

“How many rebounds I get?”

“Ten.”

How many rebounds Nate get?”

“Sixteen.”

“How many shots I block?”

“Eight.”

How many shots Nate block?”

“Two.”

Hayes broke into a self-satisfied smile. “Well?” he asked.

“Well, what?’

“Well, that tell you how it was to play against Nate?”

The strange catechism was Hayes’ means of pointing out that, despite his lack of experience—he’d played mostly at forward, around the free-throw line at Houston in an unorthodox 1-3-1 offense—he’d more than held his own against one of the great ones.

The performance and interview set the pattern for Hayes’ first two years as a pro—individual brilliance for an otherwise troubled team, coupled with controversy and sometimes intense arguments with teammates and opponents. Reporters heard about or saw firsthand these things and then relayed them to the public. An image as a sullen, self-serving prima donna began to build, never mind that he carried so much responsibility for the team, and never mind that he was only 22 years old and facing social experiences he’d never dreamed about as a Louisiana schoolboy.

On the court, though, there was no question about his skill. Hayes quickly found his style. Offensively, it was up to him to score for the Rockets, and he did this in abundance with either his strange, but accurate, line-drive jump shot or with spectacular running dunks. Defensively, it was up to him to rebound aggressively and lurk around the basket to block shots and close off the lane like a young Bill Russell (no accident, since Elvin had patterned his defensive play after the all-time great Celtic star).

“Prospect?” pondered Wilt Chamberlain of the Lakers after one of his early head-to-head meetings with Hayes. “He’s not a prospect—he’s here.

“Like most outstanding players,” Wilt continued, “he’s rather unique. Hayes is strong, big, can jump. He typifies today’s player—he’s quick, and he likes to run. When I came into the league, men 6-9 were slow, and they did mostly mechanical stuff. Hayes has a lot of dexterity.”

Wilt was asked to catalogue Hayes’ weak points. “I was so busy looking at his strong points, I didn’t notice any weaknesses,” he laughed. Then he turned serious. “He’s inexperienced right now. Just give him time.”

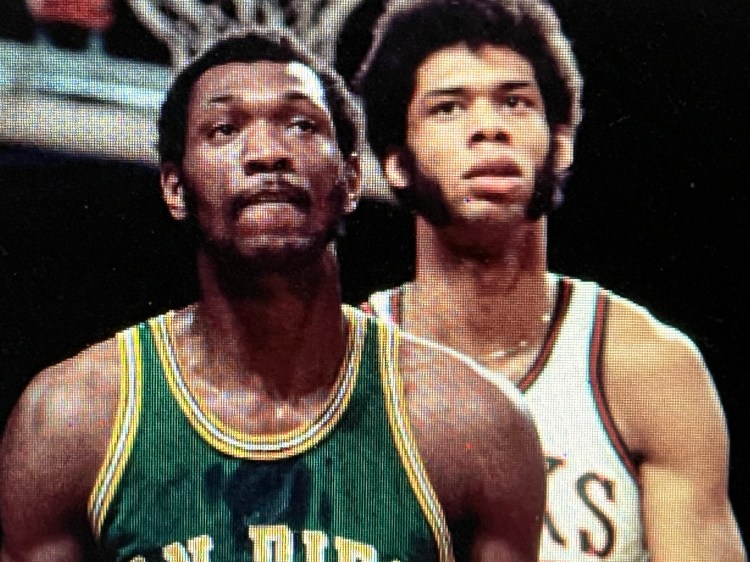

Oh yes. The Rockets lost the game, and that was the rub that rankled Elvin most. Despite his eventual league-leading 2,327 points (28.4 p.p.g. average), the Rockets weren’t winning as often in the Western Division as Baltimore was in the East with its rookie center, 6-7 Wes Unseld of Louisville, the No. 2 choice in the NBA draft who was being acclaimed as the Rookie of the Year and MVP, although Hayes outplayed him individually each time they met and also out-statisticsed him in most categories over the full season. When these two sets of votes were announced, Hayes was sought out for comment . . . and angrily claimed he’d been unfairly overlooked.

Last season, Hayes played just as well, but the Rockets didn’t do even as well as the year before. Veteran Don Kojis spent most of the season complaining that he deserved much more money than he was getting, based on what Elvin was earning. And Coach Jack McMahon’s search for a playmaking, team-leading guard who could mesh five individualists into a smooth unit was no closer to success than during the expansion club’s first season.

In early December, as the losses mounted, Hayes felt more and more—whether justifiably or not—that he was being blamed. After a bitter loss to the Lakers at the Forum—Jerry West, naturally, scored before the final buzzer to overcome a game-long Rocket lead—Hayes was caught in a particularly glum mood by a San Diego sportswriter. He proceeded to (a) berate his teammates, and (b) demand to be traded. His public image dropped another notch.

Elvin was called into the front office the next morning and instructed to apologize for the shocking statements. But the further damage to his team and to his image had already been done. Less than two weeks later, McMahon was dismissed as coach in favor of Alex Hannum, returning to the NBA after an ill-fated, one-year experience in the ABA.

Under the dire circumstances of the moment, a change inevitably had to be made. McMahon’s coaching credentials are strong, and he later was sought out to take command of the ABA Pittsburgh team. But he hadn’t gotten through to Hayes or to enough of the others.

Hannum, a former teammate and still close friend of McMahon’s, started fresh with Hayes and plunged into the task—along with general manager Pete Newell—of building toward the future. Hannum experimented with various combinations of players the rest of the season (Hayes, the one man who stayed in the lineup most of the time) and won just 18 of 54 remaining games while looking to the future. That included selling Kojis to Seattle for the sake of harmony.

McMahon’s approach to basketball is steady, the cute Eastern-style requiring clever backcourt play and demanding finesse. Hannum’s teams traditionally have been more muscular, more motivated by Alex’s high-pitched chirping, and, on the eve of the current season, the change gave promise of turning Elvin’s personal frustration and the team’s floundering into success at last.

“It was like Alex sent me back to college,” Hayes said with enthusiasm not long ago, recalling his first opportunity to spend a full preseason training period under Hannum’s direction.

“Alex was a big man himself,” Hayes fairly bubbled, “and he could help me. He gave me more time, taught me different moves, showed me how to play the pivot position. He helped me on my range of shots, my defense . . . the total game. I really respect him. He really makes you want to play. He’s been around 22 years. He really knows the game, and he can put it into your head. Everybody on the team wants to play.”

It was the first of many interviews in this era of his career in which Elvin has spoken warmly of other Rockets, and he continued with praise for trade-acquired Larry Siegfried, the Rockets’ new floor leader, and the tiny Calvin Murphy, the 5-foot-9 rookie mini-marvel from Niagara (“He’s small, but he’s gonna run guys crazy,” Hayes laughs).

There are other developments, which indicate Hayes has outgrown the moods and problems of his first two seasons, the most important of which is an involvement with a San Diego-based organization campaigning on behalf of servicemen captured in combat by North Vietnam. “I attended a luncheon in San Diego early in the summer,” Hayes reported, “and I was really touched by the problems of the wives. The kids don’t know if their fathers are alive or dead.”

The organization is called Concern for Prisoners of War, Inc., organized by San Diegoan Joe McCain, whose brother [the now late Senator John McCain] has been a prisoner of war since 1967. With Hayes’ help, the organization arranged with the Rockets to have the team’s opening game last October 20 dedicated in its honor and to share in gate receipts. “Our treasury now has less than $200 in it,” McCain said at the time, “so you can see what a miracle this is for us.” McCain went on to explain that there are 1,600 U.S. male prisoners are missing in Southeast Asia, and that the nonprofit corporation is determined to convince the North Vietnamese government to conform to the 1949 Geneva Convention on treatment of captured prisoners of war.

“I heard Lt. Frishman (Navy fighter pilot Robert Frishman of Long Beach, Calif.) talk at that luncheon,” said Hayes. “He told me about how he dropped from 205 pounds to 130 after he was shot down, captured, and before he was able to escape. He said POWs are tortured and humiliated, that their meals are pumpkin soup, pig fat, and bad water. I wanted to do something. The guys who have say-so should pitch in. We need everybody we can get.”

So, during the summer, Hayes took part in meetings and planning with the group. “Working in the city during the summer, I met a lot of people,” he said. “’You’re really amazing,’ lots of them said after a while. ‘I know something must be really bugging you.’ Once people understand, once people know you, you can reach them. I think people should get better personal relationships with players. They realize better what being a pro ballplayer is like.”

Instead of enjoying next summer at home in San Diego with his wife, Erna, and their three-year- old son, Hayes already is planning to travel to Europe with officials of “Concern” to ask assistance from foreign government leaders to help persuade North Vietnam to improve the treatment of POWs, perhaps even free them.

But first, there’s this year of basketball for Elvin. It’s a new year for a new Elvin, really. It’s all a selfless campaign, hard to imagine for the once-brooding rookie who caused so many problems for himself and his team two years ago.

“Hayes went to see a Charger game last week,” one of his abused teammates noted that first fall. “Elvin saw [quarterback John] Hadl and [receiver Lance] Alworth and the other football players go into a huddle, and he got mad. He figured they were talking about him.”

But it’s different now.