[When Bill Walton passed away in May 2024, I’d planned to post this Q & A in his memory. But I never got around to it. So, in the name of digital spring cleaning and to mark Walton’s passing nearly a year later, here you go. Bill Walton in his own words, superlatives, and deadpan humor.

What follows is a Q & A with the Big Redhead from 1994, when Walton was doing quite a bit of broadcasting on NBA and for the Los Angeles Clippers. Things weren’t great for Walton physically, but he remained a major basketball personality and forever provocative, including here in his back and forth with Portland reporter Peter Carlin.

Their edited conversation was published in the April 1994 issue of the magazine Rip City with a heavy focus on Walton’s years as a Trail Blazer. Carlin starts things out with an intro. It runs directly below, followed by the Q & A.]

****

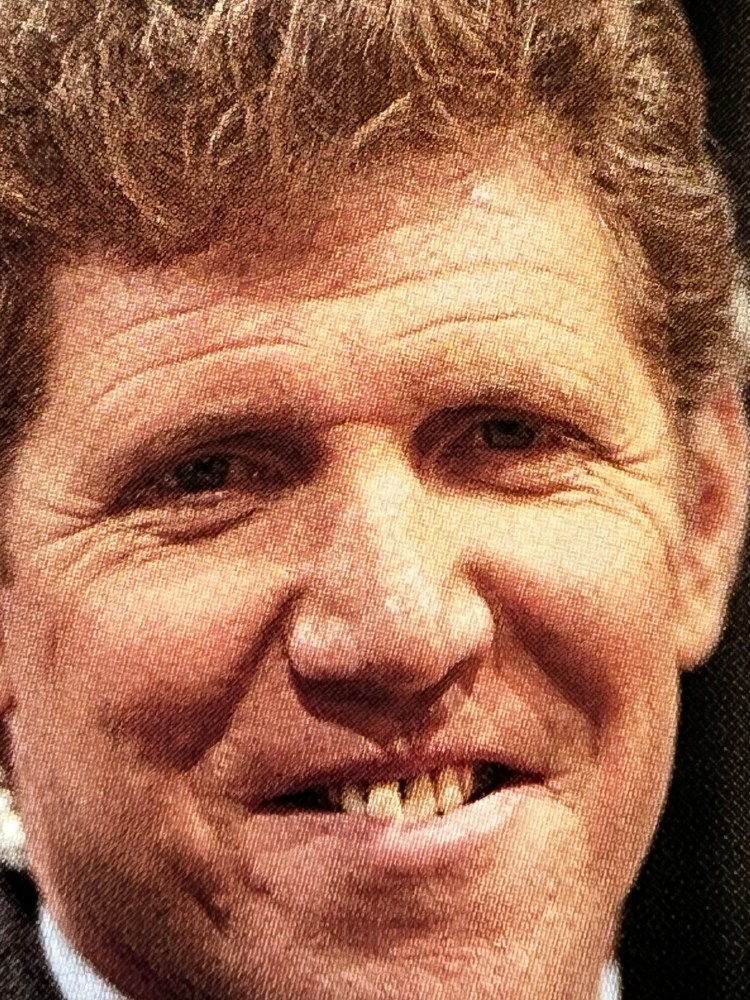

When Bill Walton glides into the downtown Portland hotel lobby, he moves so quickly you almost don’t notice the hitch in his step. His legs are long and powerful, his body still sleek and graceful. It’s easy to forget that the Hall of Fame center who led the Portland Trail Blazers to their only NBA championship in 1977 can barely walk.

Walton started his NBA career with the Portland Trail Blazers 20 years ago this fall. A brilliant, generous athlete with a white-hot sense of competition, Walton had dominated NCAA competition at UCLA. But the longer, harder NBA season wreaked havoc on the flawed bones in his feet. Walton’s professional career was bittersweet, a collision of talent, desire, and physical limitation. He played on two championship teams—Portland in 1977, and Boston in 1986—but paid a steep price for the privilege. When Walton finally retired in 1987, his battered feet required three years of surgery just to allow him to stand and stroll without pain.

A still-boyish, 41-year-old Walton recently wrote an autobiography, Nothing But Net. He now works as a broadcaster for the Los Angeles Clippers and as an anchorman for NBC Sports’ weekly NBA Insiders program. Walton’s success as a television announcer is impressive, and doubly so, when you consider that he still suffers from a serious stuttering problem.

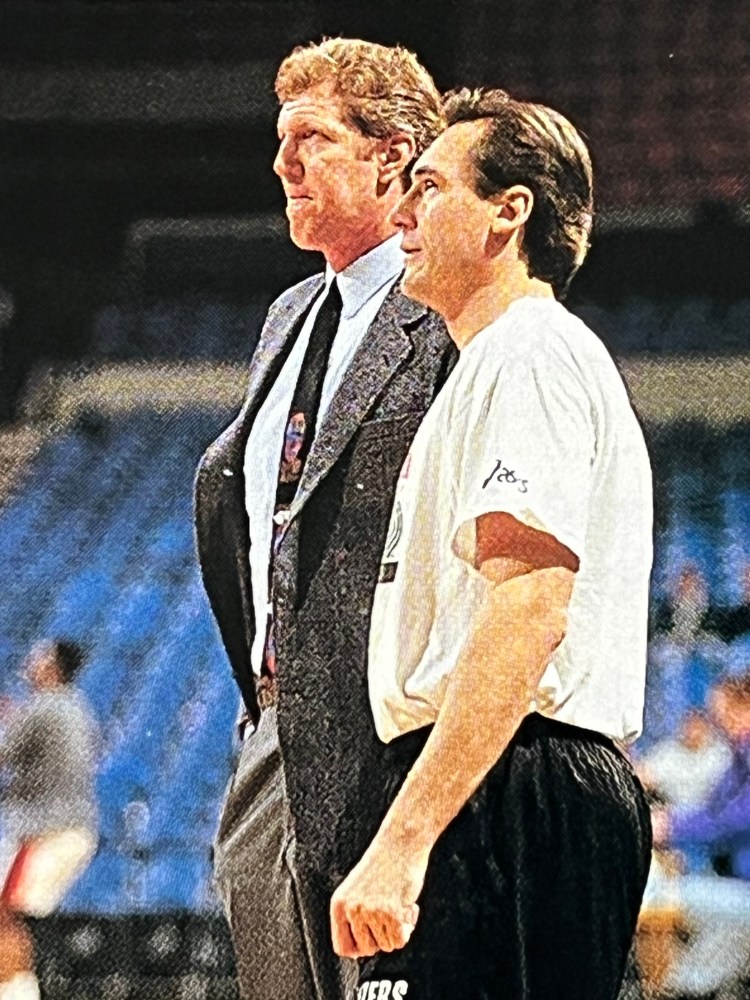

Walton is a confident man, and he demands success. This much became clear when he allowed himself to be driven from his hotel to the Memorial Coliseum one recent winter evening. The cars on Front Avenue might have had the right of way, but when he paused to wait for a break in traffic, Walton shifted into coach mode: “Don’t let those guys cut you out,” he barked.

I couldn’t tell if he was joking. Walton swung his head from side to side, watching the other cars pass us on the street. “I think they’ve got the right of way,” I explained.

Walton made a sour face. “You’ve got to be more aggressive than this,” he told me. I eventually got onto Front Avenue when the traffic cleared, but hoped to take his advice during our conversation.

****

Rip City: It’s been 20 years since you started your career with the Trail Blazers. What are your favorite memories of Portland?

Walton: The fans, the teammates, the coaches—Coach Ramsay, Lenny Wilkens. I loved the teammates here—Maurice Lucas, Johnny Davis, Lionel Hollins, and Dave Twardzik. And I really miss the building. It’s a special place. We had an unbelievable homecourt vantage here. The fans were so great—they had the best signs, the banners. They would cheer so loud. Rick Schonely’s son was in charge of the public address system before the game, and I’d bring him Grateful Dead tapes, and he played them during the warmups. I liked anything fast. Fast and loud. He’d crank it up, and by gametime, this place would be rockin’.

Rip City: I’ve been reading some of the books about your days with the Blazers, and what always impresses me is that compared to the average straight-laced jock, you were an absolute freak.

Walton: I’ve always been mainstream. Maybe you were out in right field.

Rip City: Maybe. But you lived in a commune, and you had a big beard and a ponytail dangling down your back. In Sports Illustrated, they called you the Mountain Man.

Walton: I never called myself the Mountain Man. I’ve always been Bill Walton. What other people say and do, I can’t control. Buck Williams has a beard today.

Rip City: But you were such a counterculture figure during the mid-1970s. For instance, you criticized professional sports so much, there was talk that you’d abandon the NBA and start your own semi-pro league, or just quit the pros and play in Wallace Park full-time.

Walton: Yeah, well, I did hate it when I first started. I hated the teams, the greediness, the selfishness of the players. It drove Lenny Wilkens nuts as well, but Lenny didn’t have the power to make personnel decisions. It’s impossible to be a coach if you don’t have control over your personnel. Or least reasonable control. And when he didn’t have that, and because of that, coupled with my injuries, he got fired. That was a very sad day for me. So I didn’t like it at all at first.

I always played basketball for the joy of the game, the competition, the team concept of winning games. I was never into it for the money. But I’ve always loved the NBA. Always wanted to be in the NBA, from my earliest days. Coming out of college, the ABA was going to make me the owner of a team. They were going to give me a team, and let me have any players I wanted, with the exception of Dr. J [Julius Erving]. But I turned that down to come to Portland and the NBA. I’m glad I did, and I’m still extremely proud to be part of the league. Basketball has always been my life. And it still is.

Rip City: Is it hard to be referred to as being “owned” by a team and knowing that you can be traded with no notice? I could see you might resent that.

Walton: I don’t see it that way. I think that’s the beauty of the salary cap. It makes the players part-owners, guaranteeing them a portion of the revenues. It’s a brilliant idea. But the other leagues are missing the boat when they say the salary cap keeps the league healthy just because it caps salaries. Sharing revenues creates a realization that the players need to have a sense of responsibility for promoting the event. You see the other sports where the guys don’t seem to care about the teams, don’t care about the fans, don’t care about the product that you see out on the field. It shows in their sports’ popularity.

But then you have the NBA, where the players are deeply concerned about the fans and everyone’s interrelationships. It’s truly a unique partnership between players and management, and it works to everyone’s advantage.

Rip City: What do you think at the latest generation of players?

Walton: I think the players today are bigger, faster, stronger than ever before. But there’s so much emphasis on individual spectacular play. There’s less emphasis on coaching fundamentals, which makes you able to make those individual spectacular plays. The public’s emphasis on dunking and physical play ignores the true beauty of basketball, which is mental competition. Working together to outmaneuver, outthink, and out-quick the other team.

But basketball has always been a sport dominated by personalities. And the personalities are what has always made the game so exciting. The dominating wills of individuals who are all battling for the same prize. That’s what fills up this building and every other building—the suspense, drama, and action. The uncertainty that makes it the perfect life to be a part of, to be in, to be the focal point.

Rip City: What did you think of Michael Jordan’s decision to retire [to play baseball]?

Walton: I was shocked. Disappointed. I just can’t imagine walking away from something you love to do. Jordan has done everything, but it depends on what you’re playing for. I played for myself and for my team. And that’s what I lived for. I realized I was going to leave everything I had on the court.

Rip City: When you started playing pro ball, you seemed so suspicious that the league or the franchise would force you into sacrificing your body.

Walton: Yeah, but then I put myself there. It’s not ironic—just the way I am. Basketball is very, very important to me. Success on the court is something that I needed personally. I gave it everything I had, and unfortunately it wasn’t enough. I didn’t have anything left to give.

Rip City: When you left the Blazers, you were angry at the team for encouraging you to play hurt.

Walton: I was angry at myself, too. A lot went on there. I played my best basketball right here, right here on this court. I played in Boston, but I was never the same player. And afterwards, I was just really happy that I was able, after lots of surgery, to get back to the point where I could walk around.

Rip City: How mobile are you these days?

Walton: I can walk from chair to chair.

Rip City: That must be frustrating.

Walton: My life is beyond frustrating. I’m happy that I can walk around, happy that I can go to sleep. I’m happy I’m able to work at what I do, physically. I wish I could water ski, but I can’t do anything like that. I just sit down. It’s hard, but it’s all I can do. All I’m able to do. If I try to do anything else, there’s just too much pain. But I have my interests, I’m very busy, and I enjoy my life as much as I can.

Rip City: Do you feel like you sacrificed a lot for basketball?

Walton: Everyone has sacrificed. And everyone’s got more out of it than he’s put in. The satisfaction of being part of something that’s great. Being a basketball player in the NBA, part of wonderful franchises, having such great friendships. Special personal rewards you get from playing professionally.

Rip City: So playing in the league gives you a heightened sense of reality?

Walton: It’s a very powerful stimulant. The drive it gives you. That’s where great coaching comes in—they drive you to be better and better. No matter how good you are, a great coach always pushes you to be better.

Rip City: Is that healthy?

Walton: Oh, that’s the best thing about it. Your ability to get near perfection makes it so worthwhile, because the more you work at it, the better you get. Not just the two hours you’re on the court, but the 18, 19, 20 hours a day that you’re awake, thinking about the game, thinking what you’re going to do, the strategy, your quickness. You dream about it all the time, dreaming about the game at night, and you wake up at night and you know you’ve got it. I know things are going well when you dream about playing basketball.

Rip City: Do you still dream about it?

Walton: I dream about basketball all the time, but I only dream about playing the game every now and then. But then, I usually wake up in too much pain.

Rip City: Do your sons play basketball?

Walton: Yes. Adam’s 18, a senior in high school, and he is an excellent basketball player. He plays center—6-10 so far and still growing. He’s got a scholarship to play at Louisiana State University next year. I’m very proud of him. He’s a very fine young man. I’m very happy for his prospects to be a contributing member of society.

Nathan is a 15-year-old sophomore. A top student, a good athlete himself. Luke is a 13-year-old eighth grader, outstanding young man, and so is Christopher. He’s a 12-year-old sixth grader.

Rip City: Do you envy your son, watching him head into the front end of his career?

Walton: For all my sons, I’ll be happy if they find something in their life—basketball, literature, business, entertainment, anything—that when they wake up in the morning, they can’t wait to get started. And that’s what I love about basketball. When I wake up in the morning, I cannot wait to get going.

Rip City: What advice do you have for Adam now that he’s becoming a serious basketball player?

Walton: Keep your head directly above the midpoint between your two feet. It keeps you in balance. Balance and quickness are the two most important concepts in life.

Rip City: How did you start your broadcasting career?

Walton: It’s very interesting that I’m here. I was encouraged by two people—Charlie Jones at NBC and Pat O’Brien at CBS. I was doing work with those two guys, and they encouraged me to go into it as a career. For someone who suffers from a severe speech impediment, it’s unbelievable that I’ve been able to go into broadcasting and make my living speaking.

I was a terrible stutterer. Still am—not something you get over. You have to work at it every day. I started to get it under control when I was 28. I did interviews on camera before then . . . but very bad ones. I stuttered on camera all the time. I worked at it. Got some help from Marty Glickman, the broadcaster. He was a good friend of mine, and he helped.

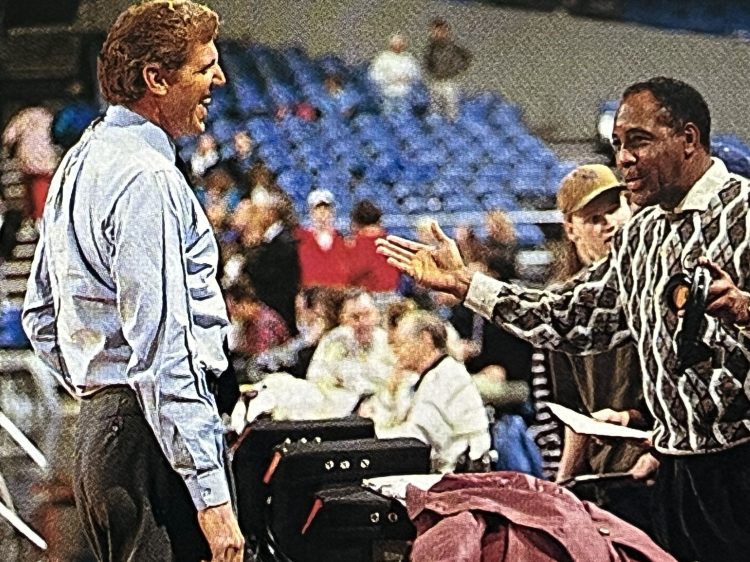

Rip City: What’s a basketball commentator’s life like?

Walton: I travel a lot and spend my weekends in New York City, which is fine. Not that I do much—I spend most of my time in my room, working the phone, keeping in touch. You have to know everything, keep in touch with everyone. Coaches, players, managers, agents, owners, the people who are making it happen.

Rip City: So big-league broadcasting allows you to flex your competitive muscles?

Walton: That happens with everything I do. I’m a very competitive guy. I just want to be the best at everything. The best dad, the best broadcaster. I want to be good at what I do, and I work really hard at it. I use the same principles that made me a successful basketball player. I learned from my parents, from the coaches I played for, the players I’ve played with. I use all those same principles in building my new career, building my new life, after that of a basketball player. My goal in broadcasting is to be part of the team that does the championships. That when the championship is there, the producer says, ‘Hey Walton, get in there and do the job.’

Rip City: You’ve been successful as a commentator, but it hasn’t always made you popular. After you criticized the Blazers in 1992, the fans started booing you when you came to work.

Walton (shrugging): Fans here have always treated me great. People are entitled to their own opinions. If they want to boo, that’s fine. I say what I believe. Always have.

Rip City: Do you still spend time with the Grateful Dead?

Walton: As much as I can.

Rip City: What music are you listening to these days?

Walton: The Dead, Bob Dylan, Neil Young, a lot of classical music.

Rip City: So, you’re true to your generation?

Walton: I don’t see me being separate from what you call ‘my generation.’ I am part of that, that is my life. I am an involved, concerned person who wants to be the best for myself, my family and friends, and everyone else.

Rip City: And you’re still politically active?

Walton: Very much so. Active socially, economically, politically. I’m out there every day.

Rip City: Are you more comfortable with the current Blazers organization than previous ones?

Walton: I’m more comfortable with myself, because I’ve learned how to speak. I’ve learned how to communicate, how to express myself. I’ve been anchored with a severe speech impediment. Now that I’ve somewhat got that under control, my life is infinitely better.

Rip City: How does it feel to see your name and number fluttering up in the rafters?

Walton: I am very proud of that. Proud of my relationship with the Trail Blazers and the wonderful team we had here. The friendships I still have to this very day. I just wish we had been able to keep our team together. I wish I would have stayed healthy. I wish it could have gone on forever.