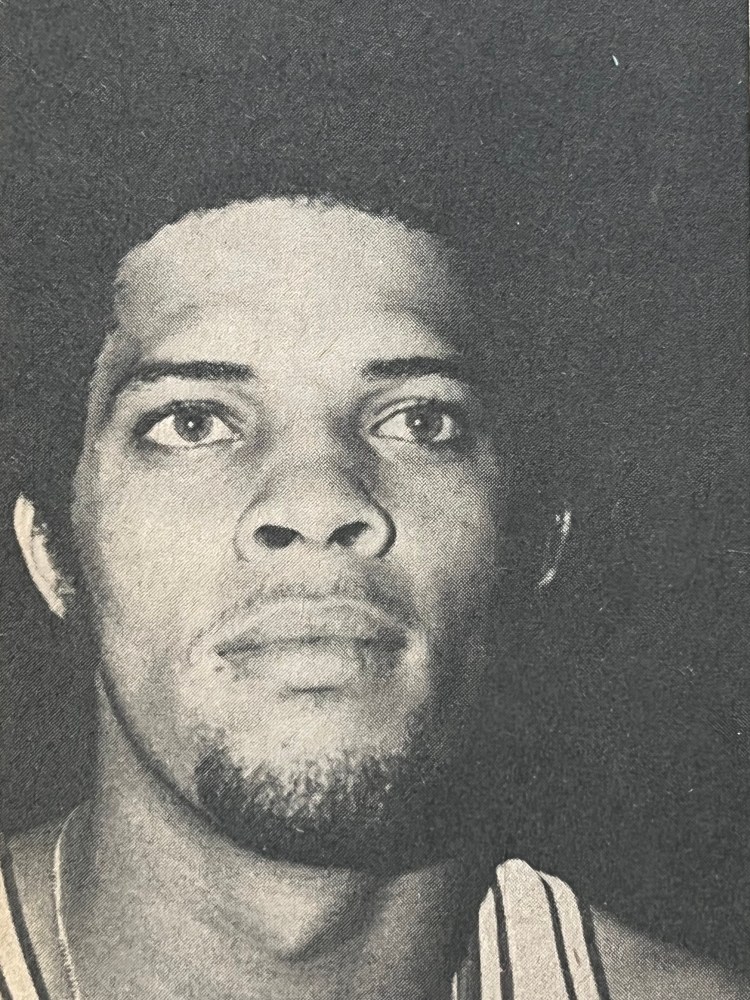

[At Long Beach State, one of college basketball’s rising mid-level programs of the early 1970s, Ed Ratleff was billed as “the Black Pete Maravich.” It was meant as a shout-out to Southern California, with its collective fixation on UCLA and USC, that Long Beach had game, too. The comparison, however, was also a total stretch. The 6-foot-6 Ratleff, though a pinpoint passer, was never a razzle-dazzle ballhandler and showman. He was a fundamentally sound ballplayer who did everything well for his size and produced on the floor.

By the end of Ratleff’s senior year in early 1973, the Long Beach sports information department thankfully backed off the Maravich comparison. Long Beach could now bask in the afterglow of Ratleff’s career achievements: three-time all-conference performer, two-time All-American, and member of the 1972 U.S. Olympic Basketball. Ratleff was also a favorite of Long Beach coach Jerry Tarkanian. “A player with Ed’s ability comes along now and then,” said Tarkanian, “but a player with his ability and attitude does not come along often. He’s a coach’s dream.”

By April 1973, the Houston Rockets snapped up Ratleff in the first round of the NBA draft (sixth pick overall). Popular opinion said the Rockets couldn’t go wrong with “Easy Ed,” as he was known. If Ratleff didn’t live up to his advance billing as a future NBA all-star, his considerable skills and versatility would make him a vital cog in turning things around in Houston, post Elvin Hayes, now in Washington.

By his second NBA season, Ratleff had become a cog, not an all-star. But a valuable cog he was, and Houston sportswriter George White explains why in this story that ran in a winter 1975 issue of the magazine Hoop. With that, time to take it Easy.]

****

His teammates on the Houston Rockets call him “Easy,” a natural label since it not only blends well with his first name but describes Ed Ratleff’s court demeanor perfectly.

In an occupation, where constant, frenetic energy seems to be the most important qualification for success, Ratleff stands out as something of a weirdo. To the uneducated eye, he appears the most docile player on the court, his face rarely reflecting strain, his motions reduced to the most economical possible. In short, he sometimes looks lazy when compared to those in constant turmoil around him.

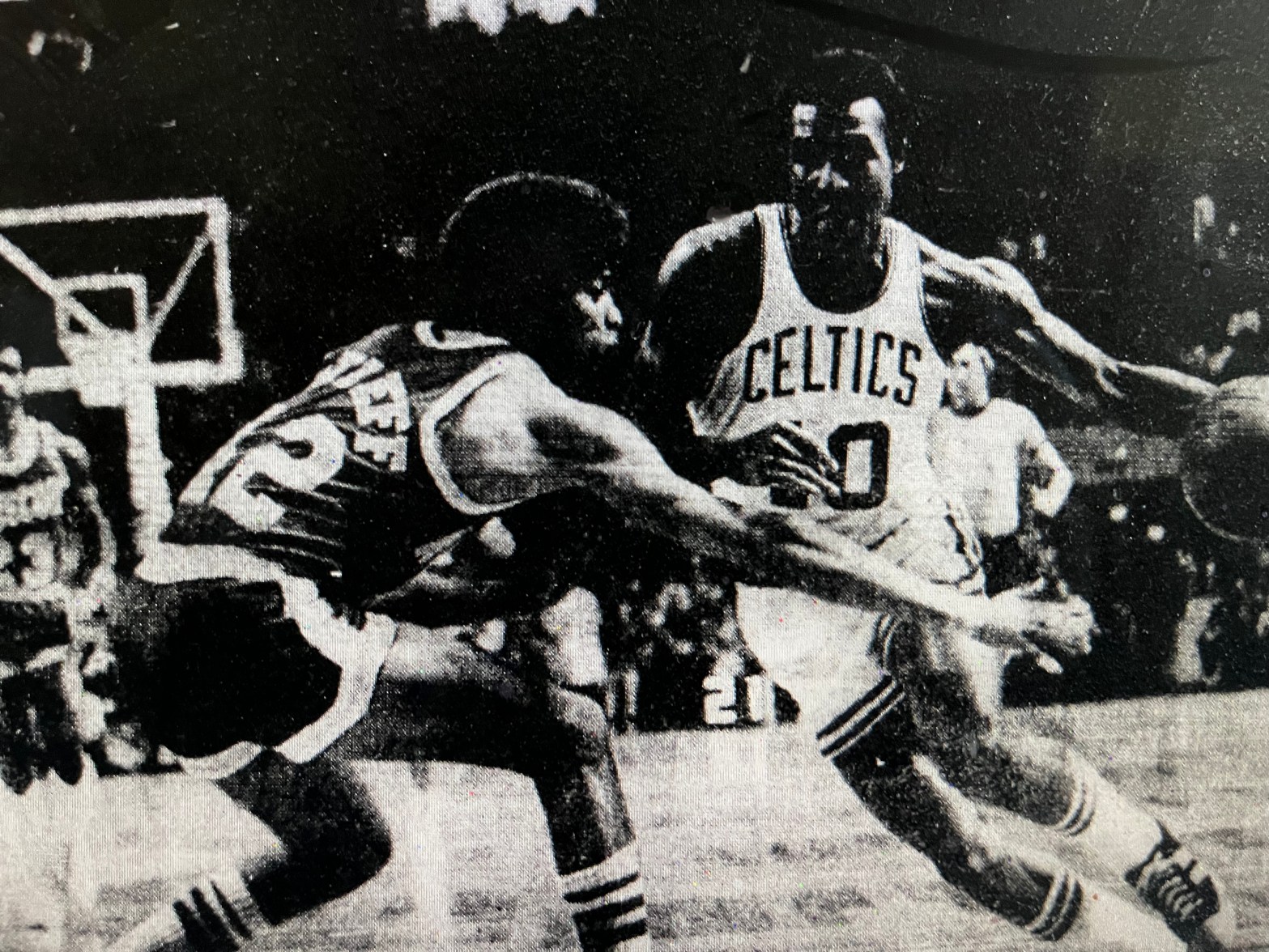

Nothing could be farther removed from the truth, says Rocket assistant coach Larry Siegfried, one of the game’s most renowned hustlers in his earlier Boston Celtic days. “I can’t recall a basketball player who played with more determination than Ed Ratleff,” says Siegfried. “If he looks like he’s moving in slow motion, it’s because he never has to waste a move to get back into position after someone has beaten him. Every move he makes has a purpose. He doesn’t just start running around out there. When he goes somewhere, he has a reason for it.”

Ratleff may have been the singular most important ingredient in Houston’s ascension to a playoff berth last season. He didn’t become a starter until the season was two months old, but when he finally was given starter’s responsibilities, the second-year, 6-foot-6 forward became the rallying point for his older, more established teammates.

“Ed is the glue that held us together,” says guard Mike Newlin. “He has held us together so many times when everyone else was breaking down and blowing assignments. When you find yourself in that rut and then you look around and see Eddie backing up everyone on the court, it’s inspiring. He is the pivotal point of our defense.”

Coach Johnny Egan says Ratleff’s presence in the Rocket lineup “became a great stabilizing factor. He is the complete team basketball player. Offensively, he is totally unselfish. He just does whatever it takes to win. Defensively, he is extremely quick, and he has gone to the trouble to develop the defensive techniques required to guard the league’s best scorers. He’s the kind of player you can build a team around.”

Veteran guard Calvin Murphy is amazed at the court maturity of the 25-year-old. “Ed plays the game like he’s been in the National Basketball Association a million years,” says Murphy. “I would have as much confidence in him in the last second of a game as I would anybody in the league.”

Ratleff may have been at his pinnacle late in the season when the Rockets were battling down the stretch with Cleveland and New York for a playoff position. In one four-game period, he defended John Johnson, Billy Cunningham, Bingo Smith, and Chet Walker, and held all four of those offensively talented forwards under 20 points. The Rockets also won all four games.

A week earlier, he had been the feature attraction in Houston’s overtime win over eventual league champion Golden State on the Warriors’ homecourt. He scored eight of the Rockets’ final 12 points in regulation time to help send it into the extra period. Then, in the overtime, he had the momentous task of guarding Rick Barry. Super Rick could get off only three shots in the five-minute period, making just one. The Rockets left Oakland 112-108 winners.

Again, in the final month of the season, Ratleff’s stellar defensive work saved a victory for the Rockets. He had scored 29 points against Phoenix, and the Rockets had rolled up a sizable early lead. But with time running out, the Suns had mounted a new assault to cut Houston’s lead to three points.

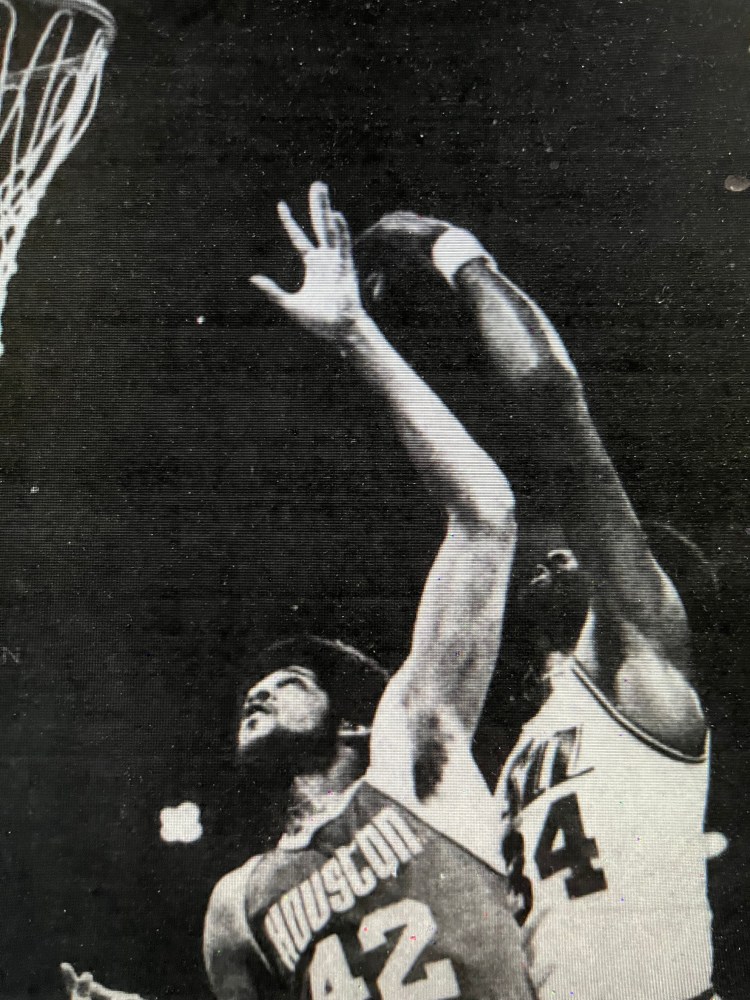

It appeared to be a one-point advantage when 6-foot-10 Dennis Awtrey accepted a pass 10 feet from the basket with nary a Rocket to contest him for the easy shot. Except one. As Awtrey lifted the ball over his head preparing to push in the easy basket, Ratleff came soaring in from the side, batted the ball off course as it left Awtrey’s fingertips, then zipped downcourt on the front end of a Rocket fastbreak. Two passes later he got possession, underhanded a layup, and Houston’s lead was again a safe five points.

But there was more. In the opening round of the playoffs with the veteran New York Knicks as the opponent, Ed again shook off the pressure to do a championship job guarding Bill Bradley. Ratleff held Bradley to three baskets in each of the three games (20 total points), while he himself scored 36. In addition, Ratleff outrebounded the Knick star, 18-8, in the three-game series.

Ed said his success in the playoffs merely reflects his outlook towards the game—never letting “pressure” exert its influence on him. “I never think of a full game as pressure,” Ratleff says. “I think of a shot in the last five seconds as pressure or trying to stop another team from scoring when they are trying to get off a last-second shot as pressure. But I never feel pressure before a game.

“The problem with a big series like the one against New York is that some people tend to get too emotionally up for it. If you get too high, then you find yourself tied in knots when you get out there,” Ed goes on.

“I try not to get too high after a win or too low after a loss. You play to the utmost of your capabilities and then accept the results. That’s the only way you can keep your emotions on an even keel in athletics,” he concludes.

Another reason Ratleff doesn’t let the “big games” pressure him into panic is because he doesn’t live in mortal dread of failure. “I just refuse to let myself get shook up,” he says. “I know that every player who’s ever played this game, from the greatest superstar on down, has made mistakes. I know I am going to make mistakes. Everyone is going to. So I don’t worry about it—ever. That’s when you lose your poise—when you become overly conscious of making mistakes.”

So, regardless of how he gets the job done moving about the court in his relaxed, easy-going way, Ratleff has made believers of the NBA. “He’s a winner, and don’t ask me to define that overworked phrase because I can’t,” says Mike Newlin. “But it’s a trait that’s unmistakable those rare times when you really see it. It’s too bad the word is so overused, because here is a person to whom ‘winner’ definitely applies.”

[A winner he was, but Ratleff never dominated the stat sheet in Houston. In his third season, Ratleff’s numbers closely mirrored those of the previous year at 11.1 points, 5.3 rebounds, 3.6 assists per game. Ironically, some of the sameness in his stat line owed to coach Johnny Egan playing with his lineup and moving around Ratleff like a checker piece. Still, Egan remained glad that he’d drafted Ratleff: “You build winning franchises with players like Eddie . . . Eddie moves the ball for us. He’s not a gunner, he plays the team concept I preach, and on defense, I rate him as my most consistent player.”

Ratleff was consistent but not indestructible. He ruptured a disc in his lower back during the next preseason that left him in agony. Surgery ensued, followed by months on the injured list to start the 1976-77 season. When Ratleff returned to action around midseason, he had to manage the severe chronic pain in his lower back while also trying to shed extra weight gained during his convalescence, get into game shape, and learn a new system under Egan’s replacement, Tom Nissalke. Ratleff struggled with all of the above, fell out of the Rockets’ rotation, and saw no action during the 1977 playoffs. The media vultures started circling. “Came into league with impressive credentials,” wrote one publication, “but [Ratleff] has never developed into anything more than a dependable reserve. Is not sending out any laundry this summer.”

But Ratleff did manage to send out his laundry in Houston for one more, though mostly lackluster, season (1977-78) off the bench. That’s all his aching back could handle. The Rockets released him, and soon Ratleff returned to Long Beach State to finish up his degree and serve as an assistant coach to Tarkanian. “If my back feels halfway decent,” he vowed, “I’m going to go back and try it again. But I’m not really counting on it.” He got the degree, but never played again in the NBA.]