[Hard to believe, but it’s been nearly five years since Celtic great Tom Heinsohn passed away. So much to remember about his life well lived, and this article from the May 1975 issue of SPORT Magazine, tells the story of Heinsohn following in the wide footsteps of Bill Russell to coach the Celtics to NBA glory in the early 1970s. Telling the tale is Don Kowet, a fantastic sportswriter from way back when who would later thrive and catch much heat as a media critic. Enjoy!]

****

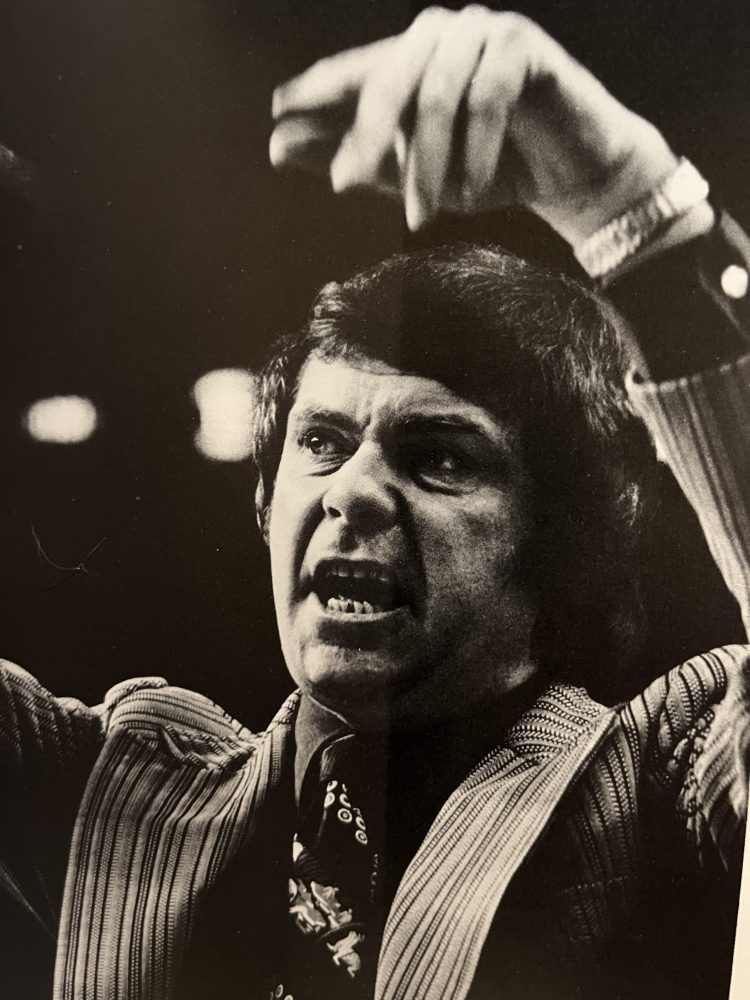

On the worst day of Tom Heinsohn’s life, back in the early 1960s when he was playing basketball for the Boston Celtics and selling insurance on the side, he (a) got a phone call from a prospective client canceling a planned $150,000 policy, (b) got a parking ticket while he was taping his daily radio sports show, (c) got a speeding ticket while he was driving to practice, (d) got fined for arriving late at practice, (e) got screamed at for the quality of his play during practice, (f) got $150 stolen from his wallet during the workout, and (g) finally, got a mild word of encouragement—“Forget it, kid”—and a cigar from his coach, Red Auerbach.

On the way home from the Boston Garden after practice, Heinsohn lit the gift cigar.

It exploded.

Almost a decade later, Red Auerbach, by then general manager of the Celtics, announced that the team’s new coach was Tommy Heinsohn. A lot of people thought that was a funnier joke.

****

When Bill Russell decided in 1969 that, after leading the Celtics to 11 National Basketball Association championships in 13 seasons (the first 10 as a player under Red Auerbach, the last three as a player-coach) he no longer wished to coach or play in Boston, Auerbach surprised almost everyone by naming Heinsohn to the job. Of all the men who played for Auerbach during the Celtics’ dynasty days, Heinsohn seemed—to his critics—the one least likely to succeed as a professional coach.

The case against Heinsohn was a varied, contradictory one:

1—He was too frivolous. As a player, Heinsohn was the Celtics’ house prankster. Typically, when teammate Frank Ramsey once needled him about his frequent contributions to the Celtics’ late-to-practice fund, Heinsohn retaliated by slicing halfway through Ramsey’s shoelaces so that they snapped the next time Ramsey slipped on his sneakers. Lots of players pull gags like that, but not many can match the stunt Heinsohn staged one night when he and his wife were invited to a costume party. “Tommy went as Little Lord Fauntleroy,” Diane Heinsohn recalls. ”He wore our daughter Donna’s baby bonnet with a long ribbon, long socks . . . and bare knees. He came dancing into the party carrying a big lollipop.”

How could someone like that discipline a pro basketball team?

2—He was too intense. On court, Heinsohn was a grimacer, a snarler, a pusher, a shover, and a tripper. He looked fierce and played fiercely, apparently on the edge of sanity. Once, in theory, he deliberately provoked a fight with Wilt Chamberlain, which suggested that he had gone past the edge.

How could someone like that provide cool coaching under pressure?

3—He was too selfish. Heinsohn’s nickname was “Tommy Gun,” even though he never held up a train or robbed a bank. In nine NBA seasons, he took 19,303 shots, or almost two every three minutes he was on the court. (Of course he passed, too, but not very often; he averaged one assist for every 15 shots he took.) Once, when Heinsohn had to have an injured right elbow bandaged, teammate Jim Loscutoff warned him that the bandages might slow down his shooting. “Only with my right arm,” said Heinsohn. “I can still throw up everything but Auerbach’s cigar with my left.”

How could someone like that be expected to teach young players the value of team defense?

4—He couldn’t get along with Red Auerbach. Whenever the Celtics went into a slump, which wasn’t often, Auerbach seemed to single out Heinsohn for public criticism. “He couldn’t yell at the others,” Heinsohn says, “so he was always yelling at me.”

If Heinsohn couldn’t satisfy Auerbach as a player—and he was twice All-NBA, three times Boston ‘s leading scorer, and five times in the All-Star game—how could he satisfy Auerbach as a coach?

Easy.

Red Auerbach didn’t buy the case against Tom Heinsohn. “This may surprise a few people,” Heinsohn says, “but when Red stepped down from coaching in 1966, Bill Russell wasn’t the first person he offered the job to. The first person was me. And I said, no, because Russell was still playing, and I knew I couldn’t handle Russell. I knew nobody was going to handle Russell. So I said to Red, ‘Why don’t you make Russell the coach? He’s got so much damn pride, he’ll handle himself.’”

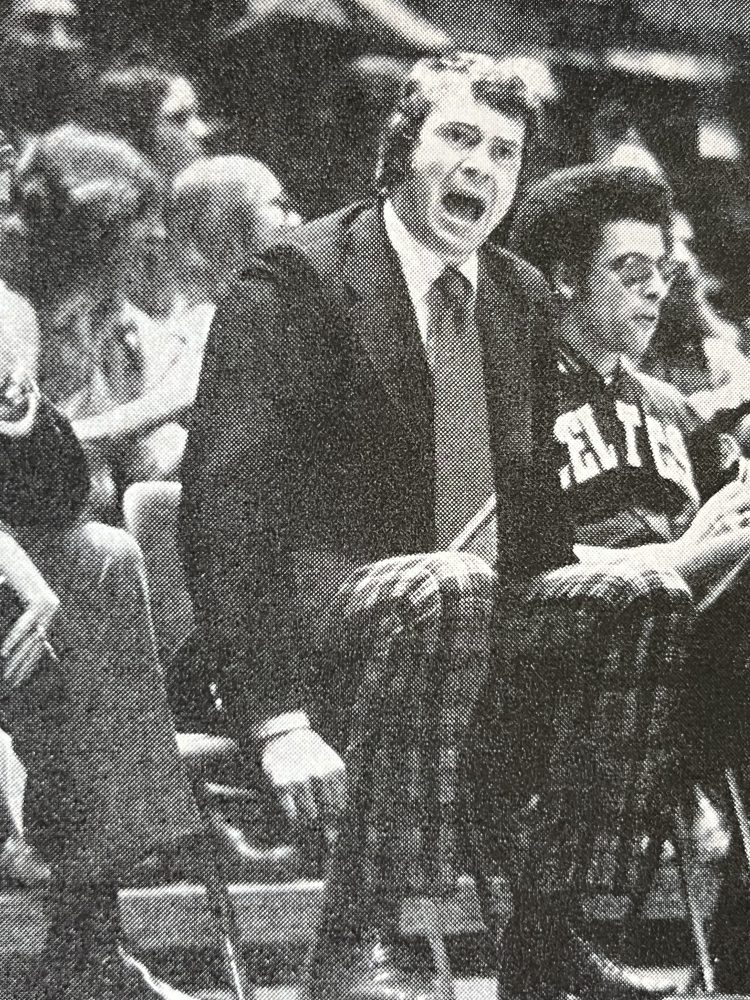

Six seasons have passed since Auerbach asked again, and Heinsohn said yes. In 1969, Heinsohn took over a fading team, a team long on winning tradition and short on winning talent. He has since rebuilt the Celtics into a basketball blitzkrieg, a team that applies relentless pressure on defense and employs endless sprinting on offense. A year ago, the rebuilding job was done, and Heinsohn coached Boston to its first NBA championship since Bill Russell stopped blocking shots. It was Heinsohn’s team, playing Heinsohn’s style, and yet there are still people who wonder seriously what method Red Auerbach uses, from his seat in the stands—hand waves, or telepathy, or smoke signals—to tell Tom Heinsohn when to switch John Havlicek to the backcourt, or when to bring Dave Cowens out to a high post.

“It’s still Red,” says Heinsohn, “it’ll always be Red. But the reason I took the job was because Red was the general manager. Red didn’t set impossible goals, and he wouldn’t be influenced by what the press said. I knew I wasn’t going to be the hero—but I knew I wasn’t going to be the scapegoat, either.”

****

Tom Heinsohn knew exactly what he was getting into, or exactly whom he was getting under, when he took the Boston coaching job. “Y’see,” Heinsohn says, “the picture Red gave of himself—that he was a dictator—was far from the truth. Red was never a dictator; he was a psychologist. And he was one of the best listeners of all time.”

But in the early months of his first coaching season, it was Heinsohn who did the listening. Auerbach coached his coach from the Boston Garden press table. Off the court, the two men spent hours together, with Auerbach outlining his theories on substitutions, personnel, and strategy. Heinsohn needed all the advice he could get. Of all the Celtic players who had significantly helped in the championship years, only five remained—John Havlicek, Don Nelson, Larry Siegfried, Bailey Howell, and Tom “Satch” Sanders—and only Nelson and Havlicek, at 29, were under the age of 30.

Heinsohn did have two young guards with potential. But Don Chaney had played only 20 games in 1968-69, his first pro season, and Jo Jo White was a raw recruit.

Still, the weaknesses at every other position paled in comparison to the vacuum at center. Bill Russell had taught the NBA how to play defense; Henry Finkel, Russell’s seven-foot replacement, could only teach the NBA how to laugh. Not that Finkel was totally lacking in talent; he could shoot, and he had muscle. But he ran as if the court were covered in six inches of water. With Finkel, the Boston fastbreak turned into a dog-paddle.

“Besides Finkel,” Heinsohn says, “I had two other centers, Richie Johnson and ‘Bad News’ Barnes. Finkel had muscle and could shoot, but couldn’t run. Barnes and Johnson could run like whippets, but they couldn’t shoot—and only Barnes had a little muscle. Well, my first year I platooned them. When we played the Knicks, for example, I put Richie Johnson against Willis Reed, and let Richie run until his tongue was hanging out. Then I put Barnes in, who could also run, and then Finkel, who could muscle Willis some, and we had success against the Knicks.”

In fact, Heinsohn’s first Celtic team beat the Knicks four games out of seven. But the Knicks won the NBA championship, and the Celtics’ record was a dismal 34-48. The next season, Auerbach was in the stands, leaving all coaching decisions to Heinsohn, and, more important, a rookie had joined the club who was going to make all future decisions easier. The rookie was a brawny, aggressive redhead from Florida State, a young man who was going to revolutionize pro basketball once his unique style was accepted. “With Dave Cowens, I was on the griddle here for two years,” Heinsohn says. “Everyone said we would never win anything with a 6-foot-8 center. But Red and I knew Cowens was Finkel and Barnes and Johnson put together. He could shoot, and he could muscle—and he could run like no big man ever had before him. He could play inside, he could play outside, and the league was in for a surprise.”

The shock waves are still reverberating. In Cowens’ first season, the Celtics’ record improved to 44-38—an accomplishment Heinsohn rates above winning the championship in 1974. (“I had to take a lot of my ballplayers by the hand and introduce them to the referees,” he says. “The referees didn’t know who the hell they were.”)

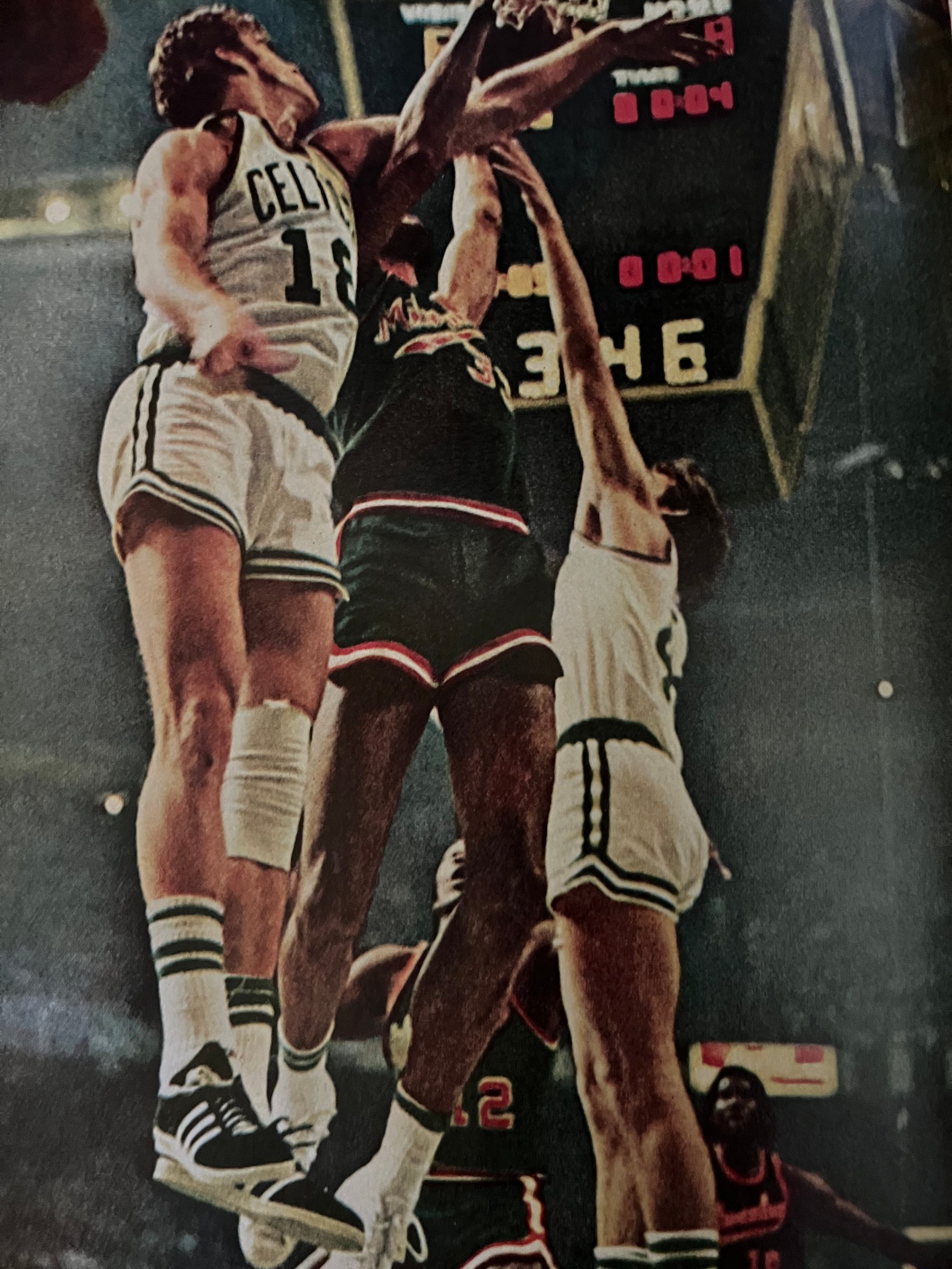

In 1971-72, the Celtics finished on top of their division with a record of 56-26. In 1972-73, when Heinsohn was chosen NBA Coach of the Year, they continued what Heinsohn calls “our progress toward excellence;” they had 68 victories and only 14 defeats, the best regular-season record in the NBA. And finally, last season, they defeated the Milwaukee Bucks in a seven-game championship series. With Cowens in the middle, Havlicek and Paul Silas and Nelson at the forwards, and Jo Jo White and Don Chaney in the backcourt, the Heinsohn Celtics were as brilliant as the Auerbach Celtics had been before them.

And this season, after a slow start, mainly due to a preseason injury to Dave Cowens, the Celtics quickly roared past the Buffalo Braves and into first place in the Atlantic Division. When they routed the New York Knicks in a midseason, back-to-back, home-and-home series by margins of 26 and 17 points, Walt Frazier summed up the sentiment throughout the league:

“They’re playing the best ball anywhere. To beat them, you’ve got to stay even on the boards and stop their running attack. We couldn’t do it.” Then Frazier added, “And who can?”

****

On paper, it seems simple: You draft Dave Cowens, swipe Paul Silas from Phoenix, then drill the whole ballclub as if each man were a candidate for the Olympic marathon. But coaching the Boston Celtics requires more than a starter’s gun and a stopwatch.

Take the case of forward Steve Kuberski, once a young Celtic, now a Milwaukee bench-warmer. Says one Celtic player: “When Kuberski first came to the Celtics, he thought he was a Fancy Dan; he wanted to stay outside and shoot. Heinsohn wanted him to be a banger, hitting people and roughing them up.

Well, one day, Heinsohn was scrimmaging with the team, and Richie Johnson had this clean break-away. Kuberski was running down the floor, screening Heinsohn out—so Heinsohn just leveled him, really creamed him. Kuberski went flying into Johnson, and the two of them landed in the stands. Kuberski was so mad, he could’ve killed Heinsohn. He ran up to Tommy yelling: ‘What did you do that for? It’s only a practice!’ And Heinsohn just looked at the guy, then said, real quiet: ‘I couldn’t let Richie get an easy layup, could I?’”

Heinsohn can coach by muscle, but, at 40, he’d rather use his mind. “Ninety-nine percent of coaching is people-things,” he says. “You’ve got to have a little empathy. For instance, Don Chaney, his first year, I worked every day after practice teaching him how to shoot. He went home that summer, he must’ve practiced every damn day for eight hours. Then he came back, and in the exhibition season, he was kicking hell out of people offensively, averaging 28 points a game.

“So, the opening game, we play the Knicks, Chaney misses his first nine or 10 shots—and his confidence goes right down the poop-shoot. From then on, he doesn’t even look at the basket.

“So, I let him go for a week, until I see his whole game is falling apart. Then, one day I grab him. I say, ‘Duck, let me ask you something. Why the hell do you think I have you on this team? Because you can average 28 points a game? Hell, no. You are on this ballclub because you have defensive abilities. You are 6-foot-5, you have long arms, we have a small team, so you give us an extra rebounder. You are quick, you will run up the floor. That is why you are a Celtic. All we’re trying to get over to you on the offense is: When you score points, it is a plus.’

“At that moment,” Heinsohn adds, “I knew that supporting the kid was far more important than teaching him the mechanics of shooting.”

****

Heinsohn absorbed his knowledge of coaching from Red Auerbach. His insights into people, he acquired from personal, and sometimes painful, experience. He was born in Newark, N. J., and his father was a supervisor in a baking plant, his mother an inventory clerk in a dime store. By nature introspective, his sensitivity was heightened by the insensitivity of others.

“It was during World War II,” he says. “We were the only family of German dissent in a neighborhood full of Italians and Irish. When I began to go to school, every day, the kids would beat me up—calling me a Nazi. So, from the age of five until the age of 12, when we moved to another neighborhood, I almost never went out of the house.”

Alone, he developed the artistic passion that would parallel his love for basketball. He began to draw, then to paint. Success in basketball as a high school All-American and as a college All-American at Holy Cross, made him a celebrity in the public world. His desire to improve as a painter forced him to explore a private world of inner space.

His first year as a pro, Heinsohn started studying painting on his own, reading books, going to museums wherever the Celtics traveled. His teammates kidded him about his hobby, until he returned from his first formal art class at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington.

“Just before the class starts.” Heinsohn remembers, “this doll waltzes in and strips in the middle of the room. I didn’t know whether to blush or cover my eyes.” When he told his teammates about the nude model, they stopped kidding him about his painting. “The next time,” he says, “they were begging to go with me.”

It is Heinsohn’s multiplicity of interests—his familiarity with commerce, athletics, and the arts—that has enabled him to develop coaching tactics fit for an era when players perceive themselves more as men than as meat.

“Tommy is more patient than Red was,” says John Havlicek, who played for both. “Red was a genius at getting his players fired up. Tommy’s main strength is that he’s learned how to teach.”

Next season, Heinsohn will have to show more tact and patience than ever. Don Chaney is jumping to the ABA, and Heinsohn will try to replace him by combining the talents of Paul Westphal and Kevin Stacom. He feels he has found the eventual replacement for John Havlicek in rookie Glenn McDonald. Even if Heinsohn affects these changes smoothly, there’s no guarantee he’ll get any more recognition for his efforts than he did one day last May—when he devised a strategy that gave him the most important single victory of his coaching career.

****

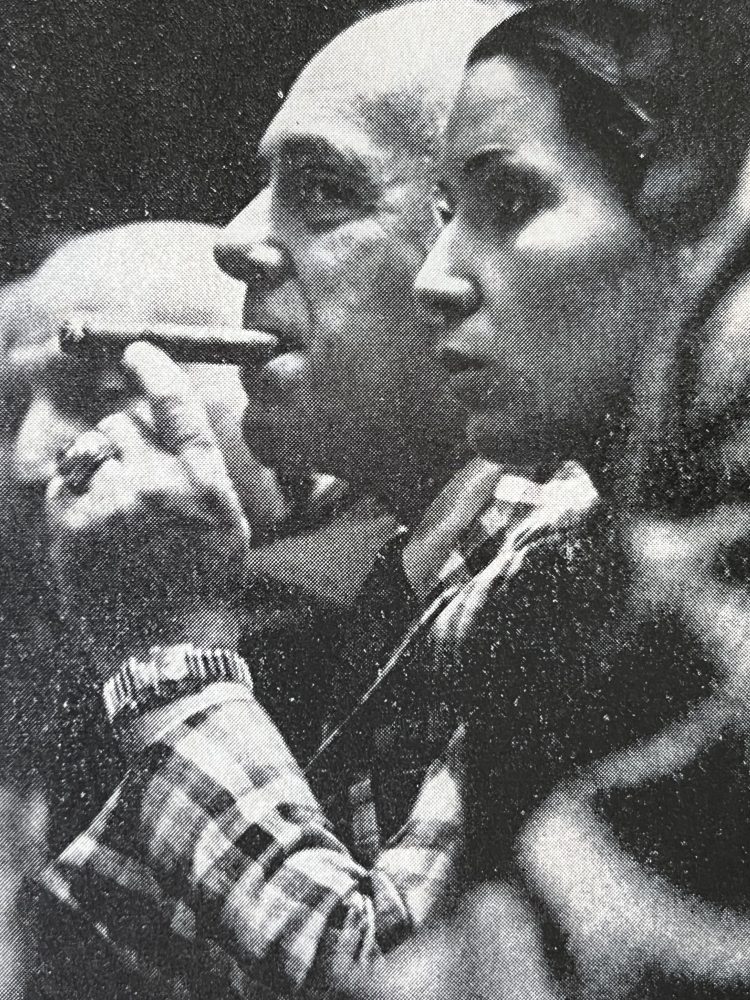

Three despondent men were sitting in Red Auerbach’s office in Boston Garden, draining cans of beer. Moments before, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar had condemned them to beer instead of champagne when, with only three seconds left in the second overtime of the sixth game of the 1974 NBA championships, his sweeping right-handed hook from 18 feet out had given the Milwaukee Bucks a 102-101 victory over the Celtics.

Now Milwaukee had the homecourt advantage for the seventh-and-deciding game, which set Heinsohn and John Killilea, his assistant coach, and Bob Cousy, who was visiting, to thinking.

All season the Celtics had used one strategy to neutralize Milwaukee’s 7-foot-2 supercenter. “Shut off everyone else, make Jabbar take on the whole burden of the offense and make Jabbar achieve greatness,” Heinsohn was fond of saying. “If he achieves greatness, okay, pal, he’s won. But as great as he can be, even Jabbar is only going to play up to his potential maybe one game out of 10.”

The problem was, the Celtics and Bucks had gone through six playoff games now, and Abdul-Jabbar had achieved greatness in half of them.

“Y’know,” Cousy said, “all last week Carl Braun and Richie Guerin and I are sitting down in Florida, watching the games on TV, and we can’t understand one thing. We’re saying, ‘Why the hell doesn’t Tommy front Jabbar—put Cowens in front of him to try to keep him from getting the ball?’”

“Well,” Heinsohn said wearily, “we have fronted him, and all that did was get Cowens in foul trouble.”

Cousy shrugged. The three were silent—until suddenly Heinsohn sat bolt upright. Turning to his assistant coach, he said, “Y’know something, John? That’s a helluvan idea for a seventh game. Suppose we change our tactics completely. We not only front Jabbar with Cowens, we set Silas low behind him, too. There’s no way they’ll ever anticipate that.”

“What about Cornell Warner?” Killilea said. “If Silas is helping out on Jabbar, who covers Warner?”

Heinsohn grinned. “Basically,” he said, “no one. In the seventh game of the championships, the last game of the season, in Milwaukee, on nationwide TV—instead of giving Jabbar the chance, I am going to give Cornell Warner a chance to achieve greatness.

“The pressure,” Heinsohn mused, “imagine the pressure this guy, who never shoots, is gonna feel when he realizes he is the only open man!”

So, in the seventh game, Paul Silas and Dave Cowens worked over Abdul-Jabbar as deliberately as a pair of Manhattan muggers. Cornell Warner resisted the temptation to achieve greatness. He scored only one point in 29 minutes. The Celtics won, 127-87.

“The next day,” Heinsohn recalls now, “I opened up the papers, and there was the headline: COUSY STRATEGY SAVES CELTICS.”

****

“I’m a villain to a lot of people—a bitcher and a moaner, a screamer and a groaner, a bucket-kicker-over,” Heinsohn says. “But I’m only that way when I coach basketball. Off the court, I’m a father and a husband, I think, I feel.

“A few weeks ago, after we had won a real tight game, Big Red (Dave Cowens) runs right off the court, puts his arm around me and says, ‘Nice game, Coach!’

“It was like someone had mistaken a picture I’d painted for a Van Gogh.”