[Mark Ribowsky made his literary name profiling Stevie Wonder, Hank Williams, Otis Redding, and other great American vocalists of our time. But Ribowsky also did some excellent work writing about the memorable sports figures of our times. That includes the magazine profile to follow of Jim McDaniels at the tail-end of his tragic pro career. Here, McDaniels is on the rebound one last time in frigid Buffalo during the 1977-78 season, and Ribowsky’s profile, published in the April 1978 issue of Black Sports, works on every level. If Jim McDaniels is your man—or your favorite NBA mystery—this profile is for you.

One quick quibble. Journalism is the first draft of history, and further research shows that McDaniels didn’t get paid in full for his Seattle contract, as Ribowsky mentions in the article. In 1974, McDaniels’s year in NBA hell, the SuperSonics duped him into signing a new contact that wasn’t guaranteed. Before the ink was dry on the new contract, McDaniels was waived right out of Seattle and the league.

How do I know this? Kentucky-based writer Gary West published it in the 2011 book Kentucky Colonels, which he co-authored with Pinky Gardner. West later told me over the phone about transcribing his candid interview with McDaniels (whom he’d known for years), then clearing the text with him before publication. Just to double-check everything, I asked one of McDaniels’ former pro teammates to call him and confirm the story. McDaniels told him it was true. I mention this only to highlight the cruelty of the system, not to quibble with Ribowsky, who couldn’t have known the true story back then. McDaniels wasn’t ready to share it.

So, here you go, starting with Ribowsky’s great lead paragraph. Enjoy!]

****

They always said it would be a cold day in hell before Jim McDaniels would play in the NBA again, so McDaniels found one. He went to Buffalo.

“Never saw anything like it,” Jim McDaniels was saying as he looked out the window of his suburban Buffalo townhouse.” I think it’s snowed just about every day since I’ve been up here, and that’s since early September. After living in the sun and fun of Redondo Beach, I wasn’t prepared for this.”

As was demonstrated by the trouble McDaniels was having with his means of transportation. “I brought my Mercedes from the coast and then found out I couldn’t use it on the roads around here. They get so slick that even a $20,000 machine with snow tires ain’t no match for a sheet of ice. The other day I almost drove off the road. The cop told me that if I want to see my next birthday, I should garage the thing until the spring and get myself a four-wheel-drive. So now I’m looking for a jeep.

“Yeah, you could say living in Buffalo is a new world.”

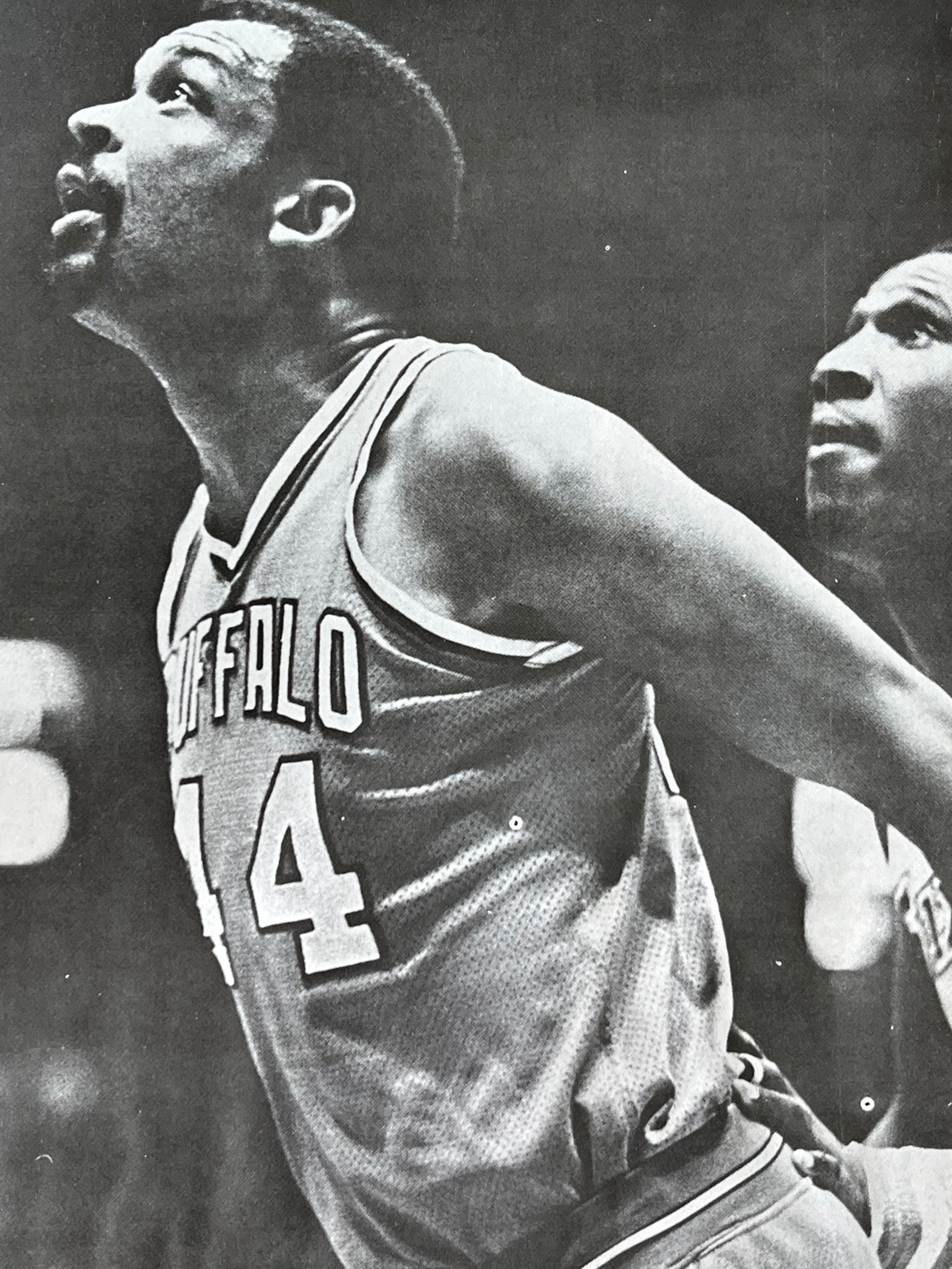

In more ways than simply coping with the uniquely horrible climate of America’s answer to Siberia. Jim McDaniels’ stock had taken such a drastic plunge during his first fling in pro basketball that if he was on Wall Street, they have kicked him off the board. Simply playing at all, then, was a new enough world for McDaniels. To be playing well—as he was—and being told so by opposing players and coaches was a whole new universe.

“I feel very good about all this,” McDaniels says. “I’m playing an important role with a club that isn’t gonna mess my head up, is gonna let me play. That’s all I asked for when I came back. I know I’m never gonna be a 20-point guy again, never going to be an all-star, never gonna get a million-dollar deal. But that’s not why I came here.

“I came back because I wanted to prove to people I wasn’t a greedy SOB. I got money. I didn’t need basketball. But I wanted to show I could still play some good ball. I took a financial loss to get my point across, but I think I have. The Braves have helped a great deal. I don’t think I would’ve accepted a pity-patty job, just as a hanger-on. I had that before. What I wanted was a meaningful role, as a back-up, yeah, but a leech, no. The Braves gave me that chance. That’s why I could be cut tomorrow and still record this as one of the best years of my life.”

It would have to be, by default. This is, after all, the guy who—for whatever reasons and whoever’s fault—went from the hottest young property in the game to a discontented SAC. And all in the space of one very hectic, very weird year.

That year was 1972, which McDaniels began in Greensboro, North Carolina, in the midst of a seemingly contented and obviously dynamic rookie season in which he averaged 27 points and 14 rebounds with the old ABA Cougars, who had signed him out of Western Kentucky—more than a few would say in Western Kentucky—for $1.4 million.

McDaniels played another couple of months in Greensboro, then suddenly claimed the Cougars had breached his contract. He wound up in the NBA playing for Seattle with a new $1.5-million deal from the Sonics. Lawyers from the Sonics and Cougars wound up in the courts from Carolina to California to Washington debating which club had a better excuse for breaking the law. The Sonic lawyers won. McDaniels lost.

By the time training camp rolled around the very next season, which would be McDaniel’s first full NBA year, the Sonics had inexplicably come to regard their new bonus baby as a white elephant and were desperately trying to unload him—so desperately that they even called Carolina trying to get the Cougars to take him back. Failing that, they sat him. And sat in. And sat him some more.

Then they got tired of providing free seating space to a spectator. In 1974, after two seasons of mediocre playing in which McDaniels averaged 15 minutes, 6 points and 5 rebounds in 107 Sonic games, they quietly cut him and his six-year contract—which they’re still paying off to this day. From a legend to a trivia question in two years. With that McDaniels vanished from the public eye.

****

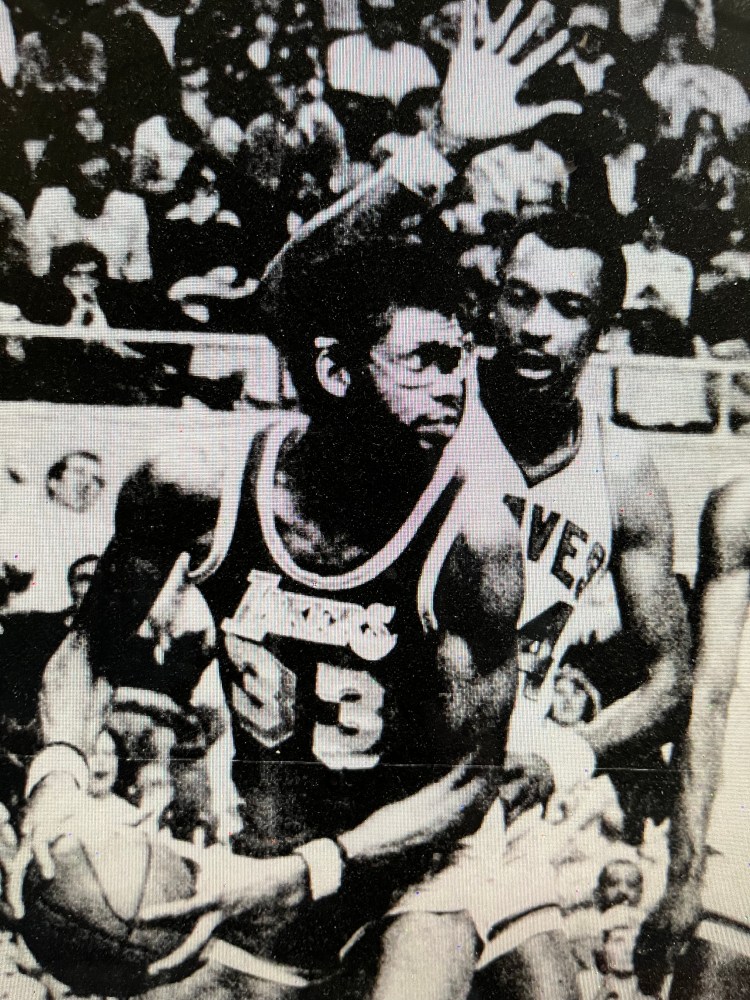

It solved the Sonic problem. It only continued McDaniels’ woes. With his Seattle reputation—and his Seattle contract—preceding him wherever he went, McDaniels found the only open pro job in Italy. He spent a year in Udine; then in 1975, came home to win a job as a back-up center with the Lakers just before the season started. Thirty-five games later (average playing time 6 minutes; average points: 2.6), he faced another cut. McDaniels jumped back to the ABA, to Kentucky. There was no screaming about his jumping this time. There was a lot of yawning, especially in Kentucky, where he averaged 6.2 points in 29 games.

It was then that Jim McDaniels said the hell with basketball, he didn’t need this crap anymore. He was 28, and if he wasn’t going to play more than a token role, he should damn well find another line of work. So he went back to Redondo Beach. He sold real estate. He worked with a production company booking rock concerts on the coast. A year went by. Then he felt the withdrawal pangs.

“I needed basketball, it just wasn’t gonna leave my system,” he says. “I said to myself, ‘Okay, I’m gonna go back one more time to find out if I was a decent ballplayer or a stiff like everyone said. See, I had to find out if all that time spent on basketball was a waste of time.

“I was different than most free agents who come to training camps in that it wasn’t a money thing. That was important to me, too, because people always said I was just interested in the money. But if it was money I was looking for, I could’ve gone back to Italy—I have an open-ended contract for a lot of money and I loved it over there. I’d learned culture, learned to speak the language, developed a taste for art and good wine. But if you’re an American basketball player, you gotta know if you’re good enough for the NBA. You can’t just think you are. You’ve got to do it.”

McDaniels ran on the beach four hours every day in heavy boots getting his 29-year-old legs in shape. Then he called the teams in the pits, the ones who’d be most open to an old guy with a bummer of a reputation. He called the Nets. No dice, too many no-cuts. Then he called John Y. Brown, who’d given him a job in Kentucky and now is the new owner of the Braves. Brown gave him the go-ahead for a tryout. McDaniels came to Buffalo. With confidence.

“I was so positive I’d make it, I brought my furniture across the country with me,” he says.

McDaniels averaged 26 points and 15 rebounds in a remarkable exhibition season. He was also lucky. The Braves drafted only two big men, and neither did anything in camp. Adrian Dantley’s trade to Indiana a few weeks before the season opened the door for a rebounder. Swen Nater, the team’s other new center, came down with a variety of hurts. McDaniels got more and more time. When the last cut was announced, Jim McDaniels was back in the NBA.

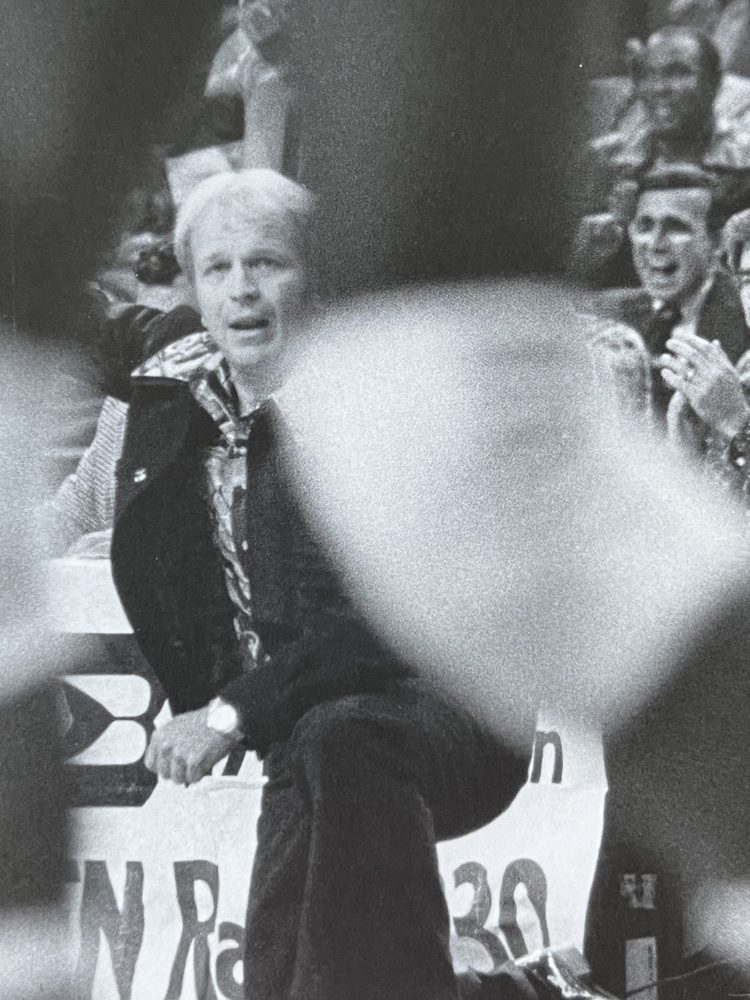

“Cotton Fitzsimmons was a fair man right from the start, his attitude wasn’t that I’d have to convince him I wasn’t a loser. If it had been, I would’ve told him what he could do with his sneakers. His attitude was that my past was forgotten, that I should do what I could do, and he’d evaluate me equally with everyone else. It was the first time I was ever on an even footing. I was always either way up or way down in the coach’s mind.

“Ever since then, it’s only gotten better. I feel like a real part of this club. Like, Swen and me, we talk about what we can do as a unit, no matter who’s on the court at the time. I haven’t averaged a lot (about 6 points at the time), but I don’t feel I have to score anymore. And I don’t feel sitting is an insult; my job is to pick up Swen. And when I get in, I play the game I always wanted to play but didn’t have the luxury to: good D, rebounding, blocked shots, the outlet pass. I don’t feel like I gotta score to earn all that money right away. The pressure is off. I can enjoy this game again.”

****

Jim McDaniels is sitting in his living room. Like everything else about the three-bedroom brick townhouse—including the occupant—the room is strikingly large. “It’s not the California beach, but it’s okay for Buffalo,” he grins.

He’s not too unhappy about the living conditions, however, because he’s not living in his winter wonderland alone. Not by a long shot. You know that immediately as you step in the door and see the tall, beautiful Black woman padding around on the living room carpet.

“Almaz, she’s my fiancée,” McDaniels says. “She’s from Ethiopia. We met in a shoe store in Redondo beach last year. I was looking at the boots. Then I saw her and—should I say it?—I knew she’d be a perfect fit.”

He and Almaz have a good laugh at the line. I mentioned the word marriage. Another laugh, but this time, not as loud. “Yeah, sure—someday,” he says. “First, I want to know a little more about my future, where it’s going. I mean, I just got divorced last year (he’s the father of a five-year-old son, Shannon, who lives with his mother in New Mexico), and I’m not gonna rush right back into it. I wanna know it’s right this time.” McDaniels grins. “So far it seems right, though. We’re just like married folks.” He grins wider. “That helps in this weather, keeps you warm at night.”

****

It is late December, and after two months of near-anonymity as a five-minute, five-point man, Jim McDaniels is suddenly becoming an important person. Things have been happening on the Braves that have been helping McDaniels surprise old critics. In an ever-consuming desire to change the facial scenery of a club with the second-worst NBA record last year, the Braves New Guard (new owner, new coach, new GM), having already traded Dantley, John Gianelli, and George Johnson before the season, had traded away two more people who could play in the pivot—John Shumate and Gus Gerard. Marvin Barnes, whom they acquired in the deal, had been AWOL after the trade and was suspended for a few weeks. All good breaks for McDaniels.

“I wasn’t playing badly but, you know, my role wasn’t particularly heavy,” he says. “I have no guaranteed contract, so I could’ve been cut at any time. If the Barnes deal had been a two-for-two, who knows, another forward and it’s goodbye Jim McDaniels. The open spot gave me more time, and I got even more when Marvin was suspended.”

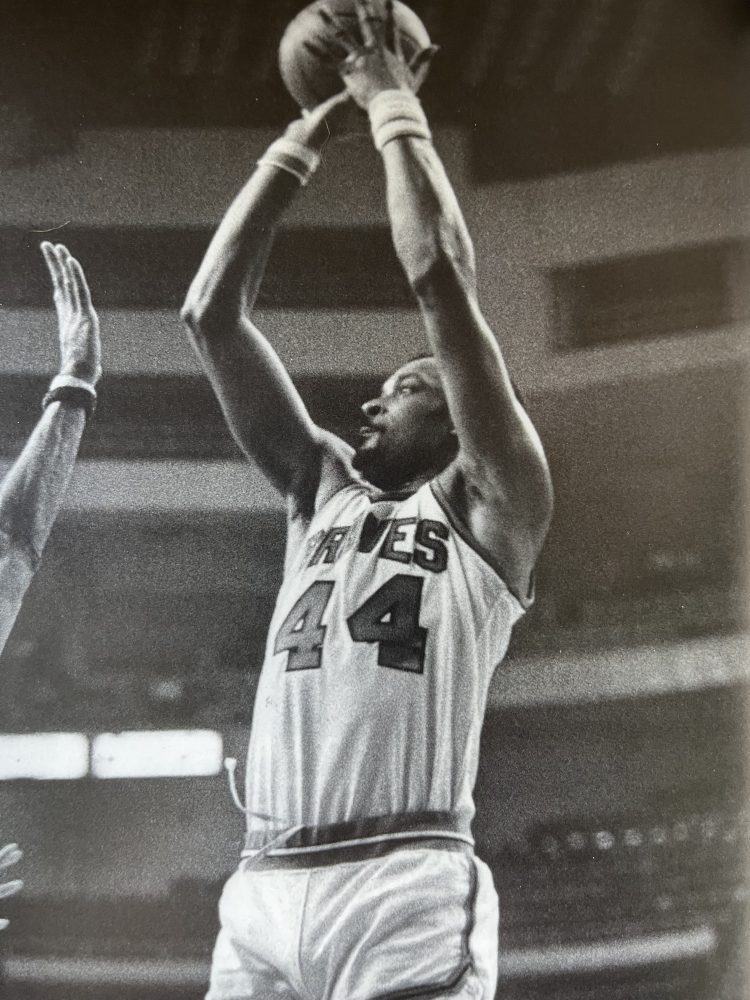

McDaniels used the time well. In one 24-minute stint against Houston on December 20, he scored 26 points in a 110-104 victory. Three nights later against the Nets, he hit 10 points and grabbed 10 rebounds in 22 minutes. Then, on December 27, when Nater hurt his ribs, McDaniels was pressed into a starting lineup for the first time in five years. Although he scored only eight against Milwaukee, McDaniels played a strong game. The next night, in Washington, he played a simply marvelous game against Wes Unseld, Elvin Hayes, and Mitch Kupchak, scoring 14 points in a 106-87 loss.

McDaniels and I first met after that game. I didn’t know what to expect from him. I remembered reading about his All-American college career at Western Kentucky, how he’d been a hang-loose kind on a hang-loose team of kids who put the school on the map with wild scoring orgies that mirrored the team’s collective personality.

McDaniels in particular had handled the heavy pressure put on him by eager pro recruiters waving wads of money under his nose by not taking basketball too seriously. I remember a little vignette of one of McDaniels’ games as a senior when, late in a tight, tense game against archrival Jacksonville, he fouled out with the Hilltoppers up by a few points and startled his coach by throwing his arms around the guy and crooning, “What’s a matter, ain’t you happy?”

But this is also a guy who was booed severely by the fans in Seattle and ridiculed regularly in the press. I wondered if his Seattle experience had destroyed that jaunty quality and turned him bitter. I began the conversation with some trepidation—and then felt very silly that I had any fears that McDaniels might clam up on me. He not only talks freely, he speaks with refreshing honesty, eloquence, and a lot of smiles. “Oh sure, I was like this in Seattle, too,” he told me. “I just never had anything to smile about.”

Not so in Buffalo. Indeed, McDaniels was positively bubbling with kid-like enthusiasm after the season in general and the Bullet game in particular.

“Let me tell you, I felt things in my game coming back to me last night that I hadn’t felt in two or three years,” he said. “You develop instincts in this game, but because I hadn’t been involved in this type of game—up and down the court all night—those instincts had kinda gone away. Once I felt them coming back—like around the third quarter—it was dynamite, man. I really thought I could put Wes and Kupchak away, and I was doing it all: blocking shots, rebounding, stopping up the middle—until my body remembered I’d been averaging less than 10 minutes the whole year. Then I kinda ran down, just like our team (a 30-19 Bullet fourth quarter broke it open), and they pulled away.

“But after the game, walking off the court, Wes told me I gave him one of the toughest games of the year, and that he always knew I could do these things. Respect. That’s what he was telling me. But, hey, I knew that during the game. When I was backing in that lane, I could feel they respected me. A lot of second-string centers, you drop off them ‘cause you know they won’t hurt you. Not so with me. I may have had some bad breaks in my career, but there isn’t a guy in this game who doesn’t know that I can play.”

****

It’s a different game he is playing this time around, a better one. McDaniels’ old game used to drive people bananas, characterized by those long jumpers a big man had no business taking and a lack of consistent rebounding and defense. McDaniels used to get ticked off when these criticisms were brought up. Now he admits he never could give much thought to the dirt work of the pivot.

“But not because I couldn’t,” he clarifies. “Nobody ever had to teach me how to play center. But how can you when you’re not playing, not cared about, and shifted back and forth from center to forward all the time? They never seemed to know where they wanted me in Seattle. I remember Bill Russell coming in and saying he’d use me as his center—and then telling people he’d measured me and found I wasn’t seven-feet but 6-10, so he didn’t have to use me in the middle.”

McDaniels laughs at the memory. “Hey, Bill Russell never measured me. He just didn’t want anyone around who is taller than he was, he had a thing about that. It was just an excuse not to play me. But what made it even sillier was he put Spencer Haywood in the middle—and he’s 6-8.

“But, see, this is the kind of thing I went through out there that made it impossible to concentrate on all-around basketball. You take the last game I started before now. I remember it like yesterday. It was early in the 1973-74 season. I got 29 points and 16 rebounds against the Bucks, all that against Kareem. We won the game, the club was like 7-2. The next night, Russell benched me. I got five minutes. Twenty games later, I was gone.”

McDaniels is at such a loss to explain just what went down his three interminable years in Seattle that he says, “By now, I’ve just about written it out of my mind. That whole era is like a big fog, everything meshes into a haze. I can’t remember that much about it—I don’t care to.”

He remembers enough to say this: “The thing that sticks in my mind most is all the quotes from coaches and management that I wasn’t the player they thought I was. But, like, they were saying that in 1972, and then brought in people like Tom Nissalke and Bill Russell who taught me nothing because they were too busy playing their own little ego games.

“The only guy who could have—and would have—taught me was Lenny Wilkens (who was player-coach of a solid, exciting 47-35 Sonic club in 1971-72). We all loved Lenny, and he was a great teacher of the game, as well as a steadying influence on the young kids like me and Spencer and Freddie Brown. So what does Sam Schulman do the next year? He up and fires the greatest coach he could have. So who’s fault is it that I wasn’t the player they thought I was?”

I mention to McDaniels the rumors that floated around the NBA in 1973 that the Sonics were lying down, partly as a protest against Wilkens’ canning and partly because they hated Nissalke—who wound up getting fired in the middle of a disastrous 26-56 season.

“No, no team loses on purpose in the NBA, guys are too professional for that,” he says. “But, yeah, guys were quite upset about Lenny, there wasn’t a good reason for it. And what made it worse was that Nissalke was confused about what to do with us. He was always acting like a drill sergeant in practice, but on the court he’d be at a loss to take decisive action. Sometimes guys would forget he was there and play for themselves. It just wasn’t a good situation, and it didn’t get better with Russell.”

I asked him, “How could Schulman spend $1.5 million and indulge in expensive court battles to get you and then not order the coaches to play you?”

A very pregnant pause. “I guess you’ll have to ask Sam Schulman. If I tried to figure it out, I’d be thinking like Sam Schulman, and I don’t want to do that. I’m too nice a person for that . . .”

Sensing his temper, starting to boil over, McDaniels stops abruptly. He switches emotional gears.

“Look man, I don’t want the story to make me look like I’m stepping on toes. That happens a lot when you say something to a writer, and he overplays certain things. See, I’m not a bitter man, really. I am and have always been a proud brother who stood up for what he thought was right. But never, not even in my darkest days in Seattle when people were using and abusing me, have I struck out at anyone.

“One of the reasons I came back was that I thought people were taking me the wrong way. I felt I was the one being abused, but I kept seeing and hearing things that I was abusing something, my position, or whatever. That hurt me deeply. I can’t tell you how hurt I was when people would send me letters calling me a spoiled and greedy man. They were like little needles.

“I remember Tom Meschery (his coach at Carolina) writing a book about me, Caught In The Pivot, the gist of which was I was a greedy bleep. But what hurt most about that was that Meschery never came to me and asked me about myself. He didn’t even know me, he didn’t even tell me he was doing a book. He was just using me, defaming me, to make some money. The people took his word for it, I have to say.

“That’s why I’m glad you’re interviewing me, face to face like this. It might be the first time someone sat down and asked me my side of things. I hope people read this and know where I’m coming from. But even if they just see me play this year, I think I will have proven my point.”

Buffalo owner John Y. Brown was one on whom the point was not lost. He voluntarily tore up McDaniels’ minimum-wage contract before the season and negotiated another. “I’ve just about been living on nothing up here, what with the expenses on the house. I had to take a definite loss to do what I felt I had to do. Now that I have, I think a little bonus is in order. But I’m not gonna beg. If he don’t give me more, I could either walk away from the game with a sense of inner peace and my head held high, or I could even go somewhere else. But I’ll never get on my knees, not for anyone. I wasn’t brought up to be a beggar.”

Jim McDaniels didn’t think he was brought up to be a basketball player either. He was born in a tiny Kentucky town called Scottsville. “Nice little community, Blacks and Whites got along—at a safe distance.” His parents divorced when Jim was an infant, and his mother brought up two sons and four daughters working as a maid. “She didn’t call it that, she said it was ‘workin’ in the white ladies’ house.’”

McDaniels can remember no greater ambition than being a barber. He didn’t see inside a gym until high school, mainly because neither his elementary nor junior high schools had one. What’s more, he didn’t much care. His only experience with basketball was shooting around in the mud at an old peach basket rim in his backyard. His first year of high school brought his first attempt to make a team.

“I had to go out for the school team because of my height (6-3 as a freshman), but I quit the first day of practice—my muscles were killing me. I said to myself, ‘Man, you’re not athlete.’”

But there’s more to the story than that. McDaniels never really felt comfortable or accepted at Scottsville High. It was mostly made up of Whites, and McDaniels, one of the few Blacks, had trouble fitting in. “I didn’t think I was being treated as a human being, either by the teachers or the kids. The White kids hung out in cliques. I felt I was being ridiculed, you know, the big Black bogeyman.”

He was so uncomfortable that he transferred to mostly Black Allen County High as a sophomore. “It wasn’t nearly as good a school, it was kind of broken down, but I felt like I belonged, I was with my own kind.” McDaniels made the Allen team as a junior and went on to become all-state.

His grades weren’t high when he graduated, but McDaniels was so good—and tall (6-9)—on the court that he could have gone the junior-college route for a year, then transferred to a big school. John Wooden offered to place him in a local school, then bring him to UCLA. Instead, he chose to go to Western Kentucky, small and nationally unknown but gearing up for a big push at big-time athletics—and determined to fight to the death for a homegrown superstar.

“I couldn’t believe it,” McDaniels says. “I got like 12,000 letters—the whole student body—asking me to go there. It was staggering, like a big organized thing just to have me come there. Then the coach, Johnny Oldham, came and told me, ‘Jim, you’re the future spirit of the Hilltoppers.’ Knocked me out. I figured if they wanted me that much, they were gonna get me.”

Clem Haskins and Greg Smith [both NBA pros] had gone to Western but never did their Hilltopper teams come close to what McDaniels’ did. From nowhere to NCAA semifinalists in four years. McDaniels and Clarence Glover, the two blithest spirits—“Clarence use to say, ‘Leave the G off my last name and you’re spelling my name correctly,’ and you know something, he was right”—on a team of uninhibited spirits led the Hilltoppers to the Ohio Valley Conference title their junior year. Losing badly to Jacksonville in the first round of the NCAA playoffs in 1970, they came back the next year and not only routed Jacksonville in the playoffs, but did the same to Adolph Rupp’s Kentucky Wildcats, chewing up the old Baron (who’d always refused to play the allegedly inferior—academically and athletically—Hilltoppers during the regular season), 107-83.

Another stunning upset, 81-78 over Ohio State, put McDaniels and his merry band of revelers in the semis against Villanova. That was the game cynics billed as a preview of next year’s ABA playoffs—McDaniels and Howard Porter possibly having already signed pro contracts. The NCAA wasn’t amused. It made both McDaniels and Porter sign sworn affidavits that they were still athletic virgins. McDaniels looks back on that little charade with perhaps more bitterness than anything that ever happened to him in Seattle.

“The NCAA is the only thing in the world I truly hate,” says McDaniels, who had to pay the NCAA $1,000 in damages in an out-of-court settlement after it sued him for perjury in signing the document (even though he still won’t say whether he actually did or didn’t have a pro contract at the time). “They never told me what I could or couldn’t do, they made all these confusing rules that kids were supposed to know. Well, I didn’t. All I know is that business students were signing with corporations. It made no sense that athletes couldn’t sign with the pros—and no one ever told me they couldn’t.

“The NCAA never gave anyone any direction. They just sat on high, like the Dali Lama or something. And they have the nerve to sue me for damages? Hell, what about the damage they did to me? They embarrassed me, my family, my friends, and my school—when the whole fault lay with them.

“If the NCAA wanted to stop early signings, they should’ve talked to the pros who were swarming over the kids like me and Porter. They should’ve sued the pros for damages. It’s the whole lousy system that was at fault. But it’s always the most innocent people—the kids who don’t know these things—who suffer for it. The kids are always the scapegoats for the NCAA’s failure to clean his own house.

“I mean, it tells you how dumb the NCAA is that I could graduate and be made a fool of while kids today turn pro as sophomores—and the NCAA helps them with the hardship draft, which is a big joke ‘cause nobody’s a hardship, they just want the money. If you ask me, the NCAA is the biggest joke of all, a pathetic organization.”

After the Hilltoppers lost to Villanova, 92-89, the Cougars announced that McDaniels—two-time All-American and 28-point, 13-rebound man—was coming to Greensboro for $1.4 million for five years. His stay would be much shorter. His breach of contract grievances – he had 18 of them – were probably aided by the Cougars’ shabby treatment of Joe Caldwell. The old pro and McDaniels’ closest friend on the club was recovering from an injury too slowly for the club to abide and was forced to play too soon. “Hey, the man was in pain, and they were treating him like he was faking it,” McDaniel says. “It was a cold, mean thing to do to a great pro like that.”

McDaniels’ general disenchantment with the ABA came to a head when, after a brilliant All-Star game performance (28 points, 18 in the last quarter), he came in second in the voting for the game’s MVP award to Dan Issel. Immediately after the game, he went on the lam and was suspended by the Cougars. When located, he was in Hollywood, schmoozing with Sam Schulman’s lawyer and unveiling his grievance with the Cougars.

There were reports in the papers that McDaniels’ claims were trivial, one grievance being that the steering wheel of the Cadillac that the Cougars gave him didn’t tilt, another being that he was demanding a $50,000 bonus for the “aggravation of playing in North Carolina.”

Says McDaniels: “That was scandalous, that they could print such lies. The Caddy thing was a total fabrication, and they got the aggravation thing all mixed up. It was for the aggravation of my contract, not living in Carolina. The only grievance was that the Cougars were changing my contract behind my back. They had agreed to deferred payments over 15 years. Then they changed it to 25. If that isn’t a valid grievance, I don’t know what is. I was right in getting out of that contract, too. Joe Caldwell’s still chasing Tedd Munchak (the owner of the now-defunct club) around the country looking for the money. I was lucky. I saw it in time to get out.”

He went to Seattle, where the merry-go-round began to turn. When McDaniels got off it, he was dizzy and confused. But not beaten.

“It’s never been a bad life, not even during the tough days,” Jim McDaniel says. “I’ve grown up without money worries and, if nothing else, that’s been a plus. But I’ve also developed a perspective on life that it can’t always come up roses. Maybe I never would’ve known that if it had all been easy. Believe me, I know a hell of a lot of people who haven’t had it half as good as me.”

Even so, Jim McDaniels couldn’t help but admit that it’s been a while since he’s felt half as good as he does these days. It’s every reason why to McDaniels didn’t even mind the Buffalo winter. You can believe he’s gone through a lot colder winters in his time.

****

A couple months later, I learn from the Braves that McDaniels has been put on waivers. “We need more defensive back-up at center and forward,” says a PR office spokesman, “and we felt that Larry McNeil could give it to us rather than Jim.”

This seems strange. McDaniels has been playing very well. I called McDaniels at home, and he is bitter; he feels he has been shafted, again.

“It wasn’t because of my ability that I was let go,” he says, “it was over my contract. John Y. Brown made an oral commitment to me during training camp that if I played with the team through December 15, my salary would be raised from $30,000 to $50,000. But when the 15th came around, I didn’t hear anything. So I played for another three weeks. My agent negotiated with the Braves for two months, and they finally said: Either you play the rest of the season at the same salary or get waived. So I stepped away. I felt like I was used; I’m not gonna be used for the rest of the season. If he thinks I’m gonna be one of his plantation players, forget it!

“What I don’t understand is how they could just discard a player who’s had good games. That’s what bothered me. I was playing good ball, I was motivated—what more do you want? I worked my behind off. I felt I was important to the team. I was helping them to win games. But the weight was on me because we were in a slump, and the guys on the bench always catch more hell. But my getting cut is a bigger loss to them.

“I’m disappointed totally by the circumstances. It was wrong, it was an insult, it was an injustice. To do all I did for $30,000! And to bring a man’s career down over something like that . . . it’s better to get out, rather than stay in, burn your body to hell, and get a pat on the head.

“There’s a lot of this kind of bullshit going down in the league, and somewhere along the line it has to stop. But basketball is a business, a cold, cold, mean business. Owners control basketball, and it’s a plantation.

“But I’m not sad for me. I wanted to play because I loved the game, and it was a good experience for me, because I learned I could play in the league. I’m gonna finish my career over in Europe. All my attention is focused there, now.”