[From Way Downtown already has published a few posts on Dave Bing’s fight for sight in 1971. Here’s one more, pulled from the December 21, 1971 issue of Basketball Weekly. This story is a little clunky in places, and I’ve cleaned up just a few sentences. But the story adds a little more perspective on Bing’s career-threatening eye injury, and that’s why I’m running it. The byline belongs to Larry Donald, who was a frequent contributor to Basketball Weekly.]

****

The crowd filed slowly into Detroit’s beautiful Cobo Arena and, with the Milwaukee Bucks in town, it was an unusually large mob scene. It wasn’t until the teams began warming up that the red, blue, and gold seats yielded to the wave of humanity.

From his seat on the Piston bench, Dave Bing enjoyed the sight. Oh, he would have preferred to be on the court weaving his basketball magic like a spider weaving a web, but Bing also understood the nature of life. He could see again.

There was another time, another recent place when Dave Bing spent 48 dark hours in an Ann Arbor, Mich. hospital wondering not if he would ever play basketball again, but rather if he would ever see again.

The soul-grinding experience began October 5 in a preseason game in New York against the Los Angeles Lakers. Happy Hairston was coming off a pick and put his hand out. Bing’s right eye got in the way.

“I thought it was just a scratched eyeball,” Bing said. “I played the rest of the game and didn’t think anything about it. The next day I couldn’t see very well, so I went to a doctor in New York. He said it was a scratched eyeball [cornea], which should heal in a couple of days. When we got back to Detroit, I went to see another doctor, and he also said the same thing, which kind of put my mind at ease.”

Bing sat out the final two preseason games to get ready for the season-opener against the New York Knicks on October 12. Still, the vision didn’t get any better. Teammate Jimmy Walker began driving Bing to practice and sensed bigger trouble was just on the horizon. “We would be driving along on the freeway, and Dave would ask me what those big green signs said,” Walker recalled. “He said he couldn’t see them.”

Still Bing made the trip to New York for the opener and, literally as a blind man, scored 24 points as the Pistons beat the Knicks. “I couldn’t see the clock or the score, and I had to keep asking Jimmy,” Bing said. “When we got home the next day, it was even worse.”

Bing faced the inevitable. He visited Dr. Morton Cox, an eye specialist in Ann Arbor, and the worst became reality. “After the examination, he came into the room and told me I didn’t have to worry about playing basketball for a while, that the retina was detached and they wanted to operate immediately,” Bing said. “It scared me to death.

“I guess the best part was that I didn’t have a long time to sit around and think about it,” he said, having been told a few more days of delay might have permanently impaired his vision. “I knew what had to be done. I was just glad I only had one night to think about it.”

One sleepless night.

It was not Bing’s first eye trouble. As a youngster, he rammed a nail into his left eye and has since had a partial vision defect. Off the court, he has worn glasses, but not while playing.

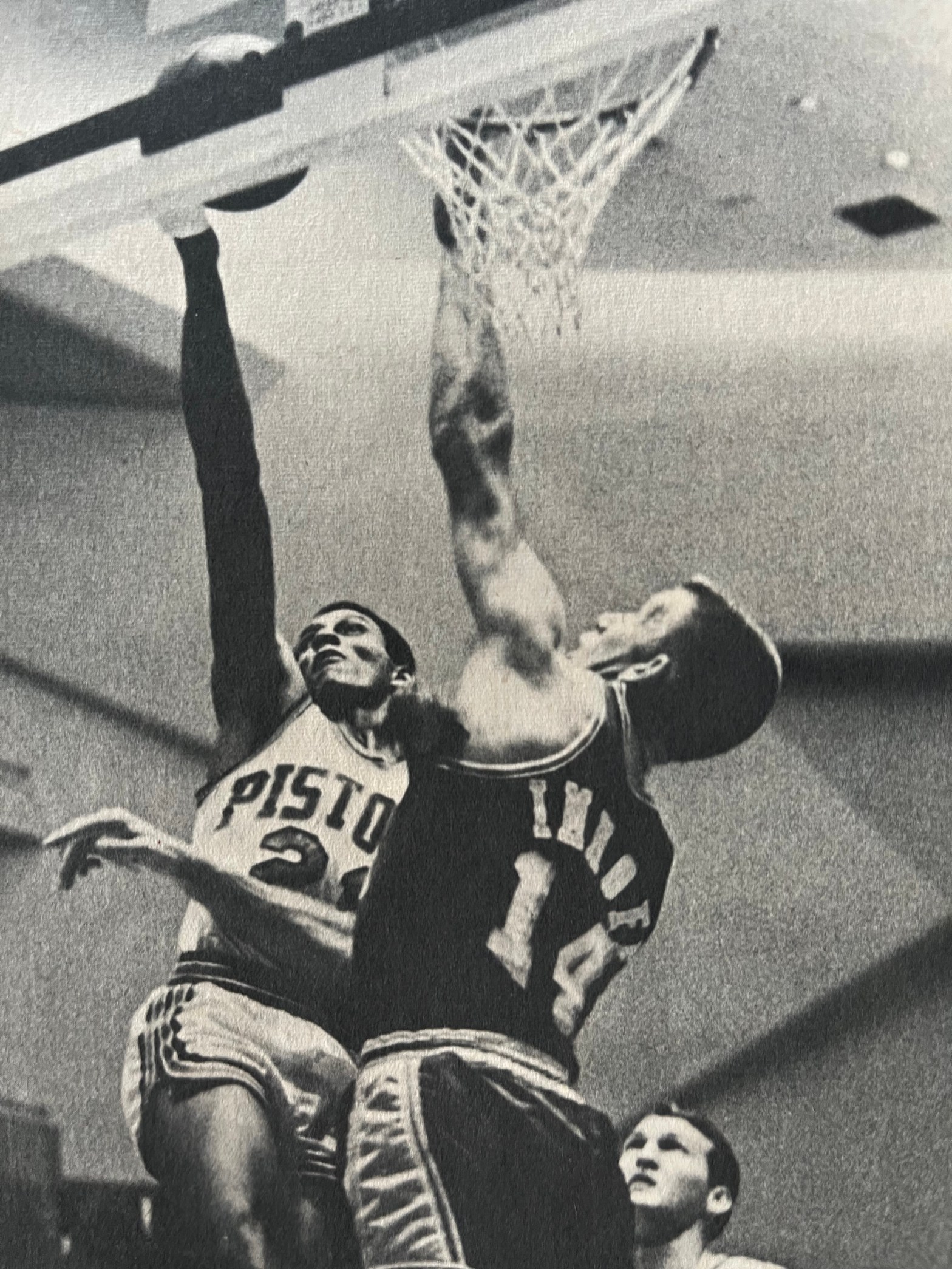

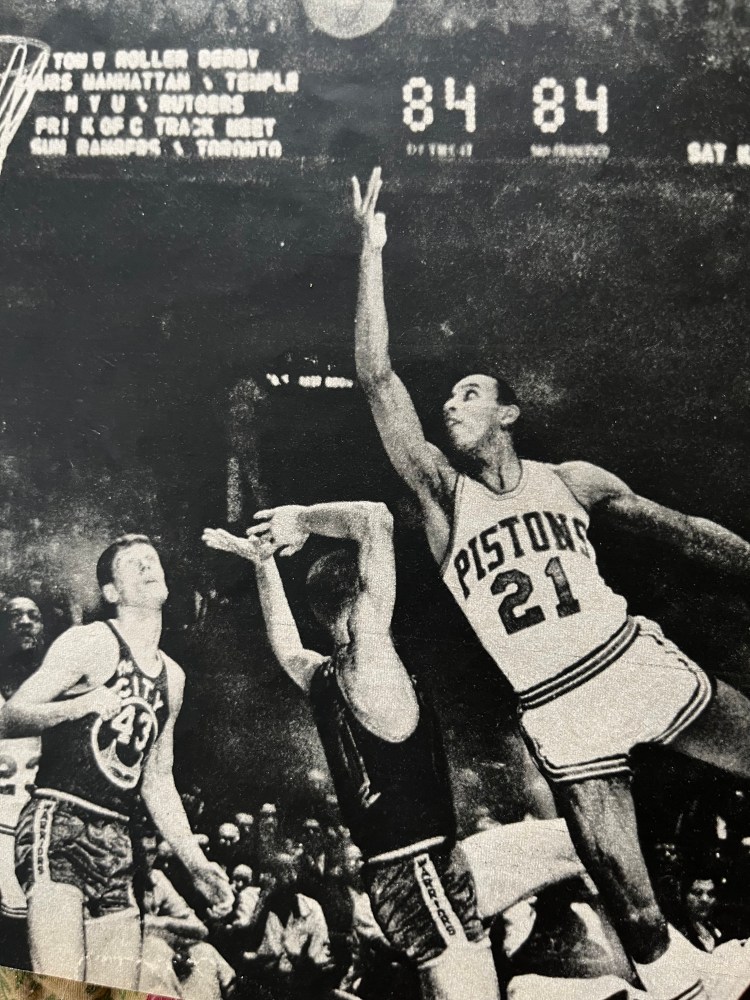

The injury never affected his shooting, obviously. Since joining the Pistons in 1966 out of Syracuse, Bing has averaged 24 points per game. He has become a true superstar, making all-pro the last two years.

Though small, 6-foot-3, and frail-looking, Bing can score inside or outside. He has the marvelous ability to hang in mid-air and get the shot away at the last possible second. As New York columnist Jim O’Brien wrote in his pro basketball handbook: “You can’t score if you are always passing off, and you can’t pass off if you are always scoring . . . Bing does both, penetrating and hitting the open man when he’s swarmed over by taller defenders.”

How remote those thoughts must have been to Bing as he lay there that mid-October 1971 weekend, patches covering both eyes, friends trying to be consoling, and nerves tingling with anxiety. “Everything was going through my mind,” he said. “I tried to think about coming back, but I couldn’t get the thought of not seeing off my mind . . .”

Lem Barney of the Detroit lions sent the game football from their victory over Denver. More seriously, several people called to say they would donate an eye if Bing couldn’t see. It was a city that reveres sports extending a hand to a superstar.

The day after the operation, technically called cryosurgery, the patch was removed from his good (left) eye. Two days later, doctors removed the patch covering the right guy. A light was shone into the eye . . . and . . . a miracle . . . Dave Bing could see you again.

“I guess when I was able to see the light, I knew I would be able to see again,” he said. “The eye was still swollen shut, but I could see the light.”

The toughest battle for Bing still lies ahead. After his release from the hospital, he was barred from strenuous activity, and watching Piston games was strenuous activity for him.

“This was the toughest part,” he said. “I listened to the games on radio and, all the time I was sitting there, I knew if I could be out there playing we would be a better team. The close games really bothered me, because I knew in my heart if I was out there, we could have won. It’s strange, but before the season, I thought this would be my best year. Physically, I was ready and I knew the team was ready.”

The convalescence period at home did not pass without incident, however. When coach Bill van Breda Kolff resigned, Piston general manager Ed Coil turned to Bing, hoping doctors would grant permission for him to coach the team until a permanent replacement could be found, probably next year.

Bing said yes, but the doctors said no. As it turns out, Bing said it is probably best he did not become the coach. “I think it would really have caused a problem once I started to play again,” he said. “I mean, how could I be yelling at the guys for making mistakes when I was making the same mistakes. Plus I think I’m too close to the guys. I guess I was just so eager to get back with the team, and this looked like a way.”

The Pistons hired Earl Lloyd to coach, and at his debut, Bing was permitted to attend the game. Bing has since been on the bench, thankful for his sight but eager to get back into action. Dr. Cox has given assurance the surgery was successful and that Bing’s vision has returned to a normal 20-20. He told Bing the retina was now in better position than it was prior to the operation.

Bing will wear glasses and likely wear contact lenses when he plays. The doctor approved some light workouts in late November, but indicated it would be mid-January 1972 before Bing would be able to play again. Meanwhile, the Pistons, starting the season with great enthusiasm, have tottered under all the adversity, but still are in position to win a playoff spot, which would be a first.

Bing’s return date could have much to do with it. “I think I can come back quicker than the doctors do,” he said. “But I’ll do what they say. I have been shooting a little and running. My biggest problem will be getting my timing. When I get back, everyone else will be in midseason form.”

Unlike others around him, Bing said he has no fear about returning. The doctors have assured him that playing basketball will not cause a reoccurrence of the injury. “Initially, there may be a subconscious fear,” he said. “I haven’t had any contact, so I don’t really know. But other things being equal, I think I can come back to where I was.

“It just seems like five years since this thing happened,” he said. “I have a religious background, which helped me a lot. But I don’t really think I’m any better person now. I’ve had operations before, and I think I know what life is about.”

Watching practice in mid-November, before doctors had given him permission to work out, the temptation to take the leather in hand and sling it at the basket, as he has done since childhood, became too great. He walked to the free throw line . . . just to see if he . . . could still . . . well . . . do it.

He made 19 in a row. Dave Bing could see again.