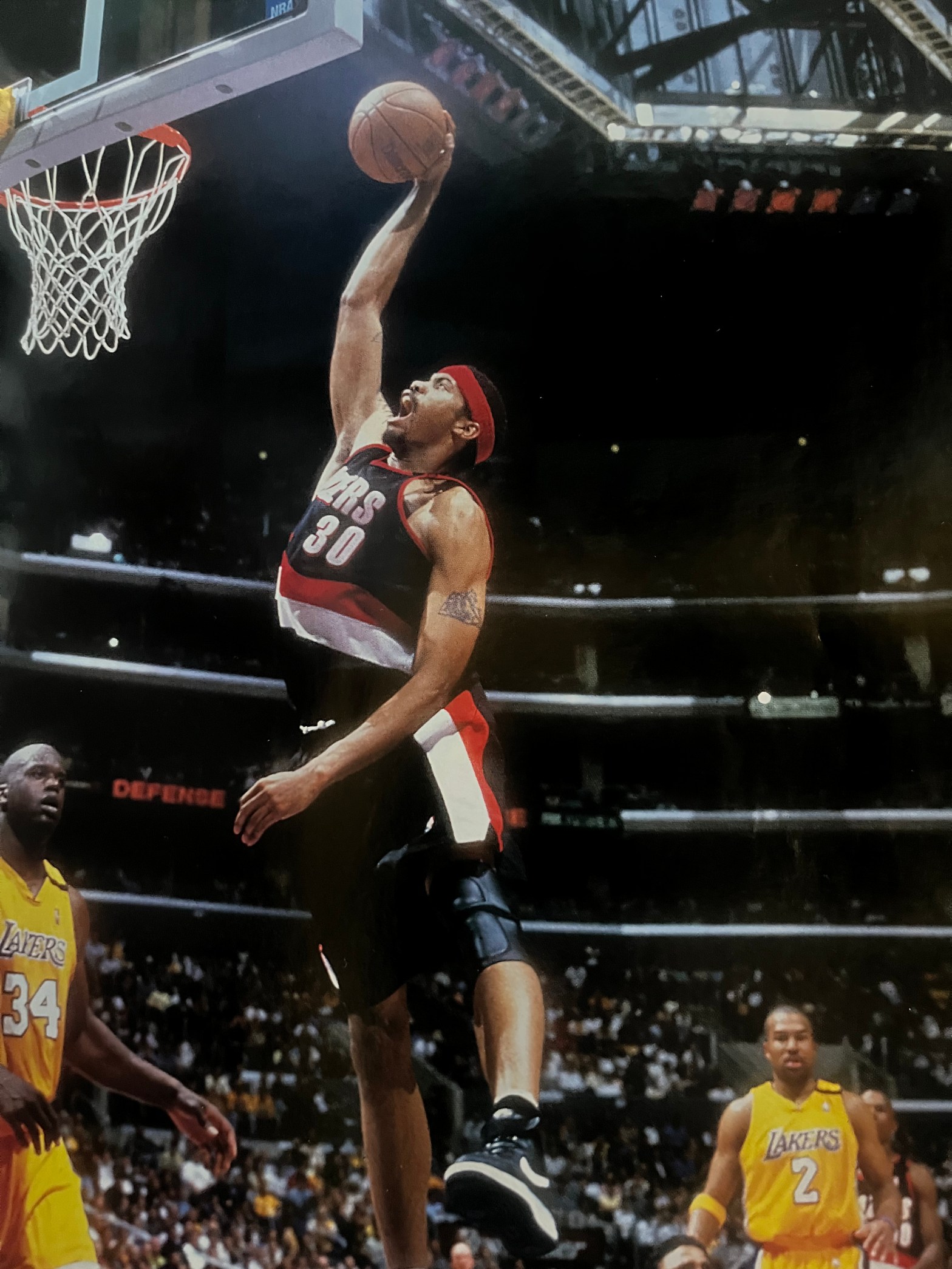

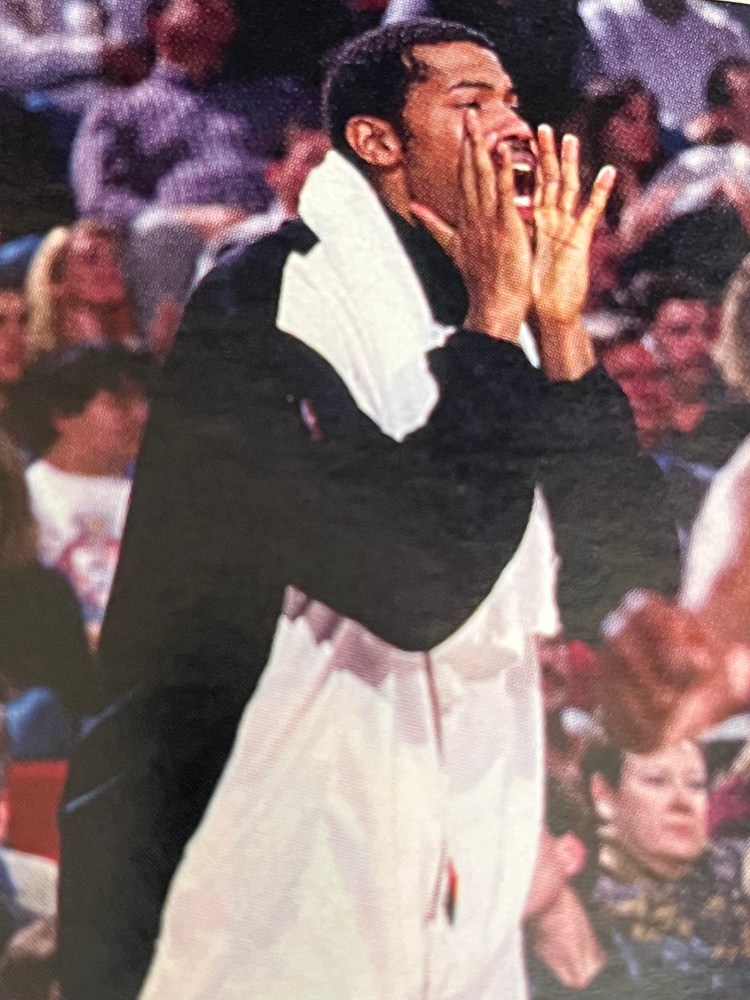

[Rasheed Wallace was always a technical foul waiting to happen. A tremendously talented big man who couldn’t control his temper on the court—no way, no how—and literally paid for it, night after night. “Guys were used to his explosions at referees,” said former NBA’er Will Perdue in Kerry Eggers’ excellent 2018 book, Jail Blazers. “You expected it. The distraction aspect of it was, you just didn’t know when it was going to happen. It was very unpredictable.”

Wallace explained: “It’s just competitiveness, and I’m a competitive person. Every once in a while, I will admit I’m wrong. On some occasions when I got the technicals, I wasn’t wrong. It was just the competitive nature coming out in me.”

The competitive outbursts and mean-mug overshadowed the fact that Wallace is a nice guy. “Off the court, outside competition, he was one of the nicest guys I’ve ever dealt with,” said Perdue. Wallace also was a trusted teammate who was ALL about championships, not statistics.

This article, from the April 1999 issue of Rip City Magazine, dives into Wallace’s willingness with the Portland Trail Blazers to come off the bench as the team’s sixth man. To quote Perdue again, “Rasheed is one of the most talented guys in the league. He was an All Star.” But Wallace just didn’t see it that way. As long-time Portland sportswriter Wayne Thompson lays out, Wallace wanted to win by any means necessary. And he did in Portland and later Detroit over his 16-season NBA career.]

****

Last May, Rasheed Wallace put on his most serious game face. As he walked into head coach Mike Dunleavy’s office for his season-ending evaluation, Wallace laid it all on the line: He was disappointed by the way the Trail Blazers had fizzled in the playoffs, and he wanted the coach to consider making a change.

No, he didn’t ask to be traded.

No, he didn’t demand to be the team’s go-to guy.

No, he didn’t want a bigger share of the Blazers’ pie.

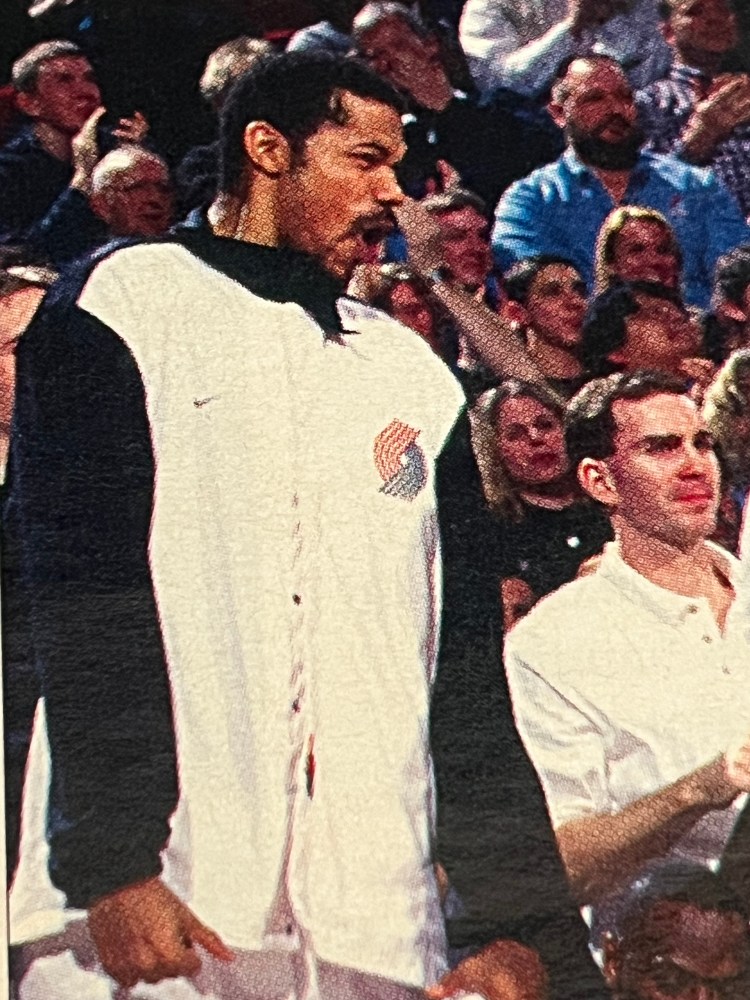

Instead, what Wallace told Dunleavy at that closed-door meeting was something slightly more rare. Wallace said that he would be willing to come off the Blazer bench in the 1998-99 season if that would make Portland a better team.

So much for the Generation X selfishness that coaches, fans, and writers so often moan about in today’s megabuck professional basketball world. At the young age of 24, Wallace seems to be a throwback to an earlier era—a Pete Rose in shorts, a Bill Russell without the bowed back, a Vince Lombardi with tattoos.

“I have no problem coming off the bench,” Wallace insists. “It’s just as important to the success of our team as starting. If I were doing this and we were losing, I’d be bothered because I’d want to be out there doing something to change things.”

But thus far, the experiment has worked. In Portland’s first 19 games, Wallace watched Walt Williams take his normal starting spot 13 times. In 11 of those games, the Blazers led the opposition at the end of the first quarter.

Blazers president/general manager Bob Whitsitt says that Wallace’s offer was almost unheard of in this league, especially for a young player. Dunleavy agrees, but with a caveat. “It didn’t surprise me,” he says. “He’s that kind of player. I can’t tell you how much that kind of attitude helps a coach and helps a franchise. Some players talk about choosing team over self, but he demonstrates it just about every night.”

Indeed, Wallace’s offer allows Dunleavy the option to match up against any team at small forward. If they want to go big, Wallace starts. If they need a shooter, Williams gets the nod. And if it’s defensive ability Dunleavy wants, Stacey Augmon can fill the void.

As his actions show, team goals are the only standards by which Wallace measures his own progress—his personal growth as a player, his personal rewards. “I can’t even remember how many points or rebounds I got yesterday, let alone what my stats were in big games,” he says.

A case in point was Wallace’s career-high 38 points on 17 of 25 field goals in a Portland win at Sacramento in 1996. “Don’t remember much about it, except that we won, and I was stroking it pretty well,” he said.

Where did this attitude originate? “I don’t know where I got that,” Wallace says modestly. “I’ve always been that way. Even in pickup playground games, back when I was 12 or 13, I wanted my team to hold the court.” Holding the court: That’s a common rule of blacktop basketball. If your team wins, you keep playing, Lose and you’re sitting out.

At Philadelphia’s Simon Gratz High School, where Wallace earned the reputation as the best player to emerge from the city since Wilt Chamberlain, things were no different. He led the school to a 26-4 record and its first city public league title since 1939. “I can’t even tell you how many points I scored, only that we won it all,” he says emphatically. “We had a great team my senior year at Simon Gratz, but even then I never thought of myself as the go-to guy. We had a lot of go-to guys, just like here.”

Wallace wasn’t the go-to guy at North Carolina either, but legendary Tar Heel coach Dean Smith has said that he had a few regrets about that after reviewing some game film of a 1995 Carolina overtime victory over archrival Duke. Smith recalled it this way: “After Rasheed entered the NBA draft, I was watching some game films over the summer. Down the stretch of that Duke game, we went to Rasheed eight straight times and eight straight times we scored. I thought to myself at the time, ‘Maybe we used him wrong. Maybe we should have gone to him more often.’”

Wallace and Jerry Stackhouse, now with the Detroit Pistons, led the Tar Heels to an NCAA Final Four finish that spring, losing to Arkansas in the semifinals. But Smith still wonders if a bigger offensive role for Rasheed might have made a difference.

Whitsitt, on the other hand, believes the structured North Carolina program has helped Wallace mature as a player faster than many others. “He’s learned early in his career that you don’t have to be the star every night to help your team win,” he says. “And with Rasheed, winning is the thing that brings the honor.”

Williams, the early recipient of Wallace’s gesture, also wasn’t surprised that he offered to come off the bench. “Sheed’s whole career has been based on winning,” Williams says. “He got to a Final Four. He’s smelled what it’s like. Yet that’s typical of the character of this team. I think all of us would give up any part of our individual game for a shot at the championship.

“Besides,” Williams jokes, “I don’t think it was totally an unselfish move on his part. I doubt that Sheed, at 6-11, wanted to be chasing around all those quick, small forwards.”

Dunleavy and Whitsitt, however, think Wallace does a very good job chasing those quick, small forwards. But they would prefer to use his superior defensive skills to check the league’s power forwards and occasionally a team’s opposing center.

Last season, Wallace heard the talk that the Blazers sometimes suffered with two natural power forwards—Wallace and Brian Grant—in matchups against quicker small forwards. Yet that’s not what motivated his offer to change his role. “I think I can guard smaller forwards pretty good because of my size,” Wallace says. “And we, as a team, do a pretty good job of rotating defensively.”

Grant thinks Wallace’s willingness to come off the bench to ignite a second unit and to play all three frontcourt positions is typical of the attitude of this year’s Blazers team. “Rasheed and I are a lot alike,” Grant says. “We’re both after championships, not stats. I’m not at all surprised that he told the coach that he would be willing to come off the bench. I would have done the same thing. He just beat me to it.”

When I asked if he was interested in competing for the NBA’s coveted Sixth Man Award, Wallace just laughs. “Oh, I wouldn’t mind getting a trophy to put up on my mantle, but that’s not a goal.”

In recent years, competition for the Sixth Man Award in the NBA has become fierce. Sometimes the honor goes to a player on the cusp of stardom, such as Kevin McHale, Detlef Schrempf, Anthony Mason, Clifford Robinson, or Toni Kukoc. Others, such as Ricky Pierce, Eddie Johnson, and Dell Curry, always fancied themselves as solid players who filled special roles.

Wallace doesn’t see himself in either category. “Starting a game isn’t as critical as finishing one,” he says. “When the game’s on the line, I want to be out there.” Wallace shrugs off the praise he’s getting from coaches and teammates for making sacrifices, suggesting that he’s not doing anything special that his teammates aren’t doing as well. “We’ve got a lot of starters on this team who are coming off the bench—guys like Jim Jackson, Greg Anthony, Stacey Augmon, and Walt,” he says. “They’ve all proven themselves as starters, so this is no special thing. It’s just part of the great chemistry we have here.”

“We’re not about numbers here, we’re about putting up wins,” Grant says, “and Rasheed is typical of that attitude.”

Adds Wallace: “Some guys groove on hitting the winning shot. I’ll take it, but what really matters is that my team takes it—and hits it.”