[One last article on Bob Cousy’s final NBA season and farewell. This is the best of the three, penned by Cousy’s coauthor and friend, Al Hirshberg. The two teamed on Cousy’s 1957 autobiography, Basketball is My Life. Here, Hirshberg looked in on Cousy’s NBA farewell for the March 1963 issue of SPORT Magazine. Last but not least, if you want a book-length account of Cousy’s final season, there’s the classic, The Last Loud Roar, coauthored by Cousy and Edward Linn.]

****

“A man makes his own shoes . . .” Satch Sanders said. He stopped, choosing his words with care. “Cousy made his . . . and nobody’s going to fill them—nobody—not ever.”

I thought of the night in 1953 when Bob Cousy electrified a Boston Garden crowd by scoring 50 points against Syracuse in a playoff game. Yes, electrified. Not today, but in those days, who but George Mikan or Joe Fulks scored 50 points? Cousy. Only Mikan, 6-10, and Fulks, 6-5, big men who did it with obvious advantages, and Cousy, 6-1, a small man who did it despite his small man’s obvious disadvantages.

Satch Sanders, Cousy’s teammate today, was only a couple of years out of grammar school then.

****

“He’s got so much class,” said Tom Heinsohn of the Celtics. He paused. “I can’t imagine who’ll take his place—”

I thought of the night in 1952 when, after an exhibition game in Raleigh, North Carolina, Chuck Cooper, the only Black player on the ballclub, wasn’t allowed to stay in the hotel with the rest of the Celtics. Cousy asked coach Red Auerbach what Cooper’s plans were.

“He’s taking a late sleeper out,” said Auerbach.

“Mind if I go with him?” Cousy asked.

“Go ahead,” said Auerbach.

Cousy walked the streets of Raleigh with Cooper until 4 o’clock in the morning, so Cooper wouldn’t be lonely in the strange city which had turned him away.

Heinsohn was a college freshman then.

****

“He’s a natural leader,” Frank Ramsey said slowly. “I’ve always looked up to him.”

I thought of the night in 1952 when Cousy was talking about the National Basketball Association, which, like Cousy, was young then. But the league was something of a laugh at that time. It was always changing cities and making new rules and firing referees, and the smart boys were saying it wouldn’t live another year. “We need class,” Cousy said then. “We’ve got to stabilize, so we can command respect.”

“Is that your job,” I asked him.

His brown eyes flashed, and he said, “It’s everybody’s job. We can’t go around apologizing because we’re professional basketball players. We’ve got to have pride—pride in ourselves and in our teams and in our league. What’s good for the NBA is good for us all—and what’s bad is bad for us all. We need a players’ association, so we can fight for these things.” Five years later, the players’ association, formed and fought for by Cousy, was formally recognized by the NBA. And people stopped laughing at the league.

When Cousy conceived the players’ association, Ramsey was a college sophomore.

****

“He does so many things well that you can’t control him,” Clyde Lovellette said.

I thought of the day I first met Cousy. It was 1947 and the scene was the Holy Cross campus. He was shy and skinny and his eyes were eager, and his shoulders narrow, and his curly black hair thick, and his face so smooth he didn’t have to shave every day.

“There’s so much to learn about this game,” he said. “I wish I could learn it all at once. I wonder if I’ll live long enough to know all there is to know about it.”

Lovellette, now in his 10th NBA year, hadn’t even entered Kansas University at the time.

****

“He means so much when he isn’t playing . . .” Sam Jones said softly. “We know he’s there and ready when we need him.”

I thought of the day in 1954 when Cousy, hobbled by a ligament sprain, came off the bench in the last minutes of the game against the St. Louis Hawks and scored two baskets in a row, then threw a swift pass to Bill Sharman for the two points that won the game. When the game ended, Cousy hobbled off the court in agony.

Sam Jones was a college sophomore then.

****

“He’s a funny guy . . .” Jim Loscutoff said. “He loves to laugh and joke and kid around.”

I thought of the day in 1951 when Cousy and Ed Macauley stole Red Auerbach’s red fedora at Ellsworth, Maine, where the Celtics were training. Auerbach was so proud of the hat that he watched it more carefully then he watched his wallet. Even when he took a shower, Auerbach put it on a chair where he could look at it. Then one day he missed it. Naked and dripping, Auerbach leaped out of the shower yelling, “Where is my hat? Who took my hat?”

“Don’t get excited, Red,” Cousy said. “I know exactly where your hat is.”

“I’ll kill you if you did anything to it,” Auerbach screamed. “Where is it””

“Right here,” Cousy said.

He pointed to an adjoining shower. Macauley, wearing Auerbach’s hat, was under the water. When Auerbach dove for the hat, Macauley tossed it to Cousy who calmly began cutting it up with a pair of scissors. Not until he got outside to his car and found a brand-new red fedora, which the boys had bought for him, was Auerbach mollified.

Loscutoff was a high school senior then.

****

“The rest of us have to think about the things we do,” K.C. Jones said. “He does them instinctively—”

I thought of the night in 1949 when Holy Cross played Loyola at the Boston Garden. With half a minute to go, one basket would win the game. Holy Cross got the ball, called a timeout. In the huddle, they agreed to hold it for one shot, which Cousy would take. They passed the ball around, killing the clock and waiting . . . and waiting for the opening.

With 10 seconds left, they made their bid. Cousy grabbed the ball and started driving for the Loyola basket. He was moving to his right, and the man guarding him, who had been overplaying him to the right all night, was with him. Cousy was boxed in, time was running out, and he couldn’t get a shot off.

He tried to shift hands, but the man stayed close. Desperate to beat the clock with that crucial shot, Cousy, without changing direction, bounced the ball behind his back with his right hand, picked it up with his left, and scored the winning basket with a left-handed hook shot. The buzzer went off, and the fans went wild.

Everyone thought Cousy had been practicing the maneuver for such an emergency. Actually, it was the first time in his life he had ever tried the behind-the-back razzle dazzle so much a part of his style today. It was an automatic reaction in an impossible situation.

K.C. Jones was a San Francisco schoolboy then.

****

“The image of the Celtics is the image of Cousy,” said Bill Russell. “He’s so great. He means so much to us.”

I thought of the basketball luncheon in 1953 when Celtics owner, Walter Brown, exploded with anger. The day before, the Celtics had looked very bad losing to the Warriors, and Cousy, the team’s top-salaried man, had scored only four points. “That’s a lot of money per point,” Brown said at the luncheon. “I don’t need an expensive club to lose. I can lose just as easily with a cheap one.”

By the time Cousy was told the story at his home in Worcester, it had been so distorted that it sounded as if the Celtics’ boss wanted to trade him. Cousy exploded with anger. On the radio show that night, Bob said, “If the Celtics aren’t satisfied with my play, I want to be traded.”

The next morning, the Boston newspapers announced that Cousy wanted to be traded. Brown, who is always losing his temper one minute and apologizing for it the next, was appalled. “We’ve got to do something to square ourselves with Cousy,” he said.

By then, Cousy had joined the ballclub in Minneapolis. Coach Red Auerbach called to his hotel room. “Look,” Red said. “Nobody wants to trade you. Get that straight.”

“Got it,” said Cousy, and there was peace on the Celtics once more.

Later, when I worked with Cousy on his autobiography, Basketball is My Life, I asked him what he would have done if the Celtics traded him. “I’d have quit,” he said. “How could I ever play for anybody but the Celtics?”

During the same period, I asked Brown if he had ever thought of trading Cousy. “Do you think I’m out of my mind?” he retorted. “I’d sell the Celtics first. Why, Cousy is the Celtics.”

Bill Russell was only a year out of McClymonds High School in Oakland then.

****

It’s going to feel funny walking into the Celtics clubhouse next year and seeing somebody else in front of Cousy’s locker. It’s going to feel funny going there knowing I won’t meet him unless he drops in as a visitor, taking time out from his job as Boston College’s basketball coach. I’m going to miss the subtle change that comes over the place when Cousy walks in, well-dressed, grinning, firing funny lines.

One cold night this past November, while a sellout crowd was gathering to watch the Celtics play the Warriors, I walked into the Boston locker room. Cousy hadn’t arrived yet. A couple of players were in one corner, autographing basketballs. Auerbach was sitting alone, reading mail. We shook hands, and I said, “What about Cousy?”

“What can you say when you know you’re going to lose the greatest backcourtman who ever lived?” Red said. “Nobody will ever take his place. There’s only one Cousy.”

He tossed the letter he was reading on his desk, leaned back and said, “You know something? He’s playing as good as ever over a given amount of time. He is 34, but, old as he is, he’s the greatest for our type of game. His attitude is just as it always was. He came to play. He never loafs. As much as he wanted to win every year, he wants to win even more now—if that’s possible.

“He’s the captain in name and the captain in action,” Red said. “He sets the pace out there. He never tells me he’s tired. I’ve got to watch him myself and pull him out when he has to be pulled.

“He’s an inspiration to the younger kids,” Red said. “He is their idol. He gives us all a morale lift.’

“Could he keep going if he wanted to?” I said.

“Sure, he could,” Red said. “He knows it. He wanted to leave last season, but we persuaded him to stay one more year.”

Sam Jones came in, and I asked him how he thinks he’ll do without Cousy. “How do you say what you can do without a guy like Cousy?” he said. “He does things so much better than the rest of us. He’s so deceptive, and he handles our fastbreak like nobody else.”

Heinsohn came into the locker room, and trainer Buddy LeRoux met him and said, “Over in the corner. Those basketballs have to be signed.”

“What do you do—sell ‘em?” Heinsohn said.

He went over to the corner, and I followed him. “What’s Cousy’s quitting mean to you?” I said.

“I won’t have anyone to ride back and forth to Worcester with,” Tom said. Then he grew serious. “We don’t move the ball as well without him,” Tom said. “We’re just going to have to work harder. We’re losing a helluva leader, too.”

“Anybody got any tickets?’

Cousy, in a brown jacket and slacks, wearing a brown tie and big grin, was standing just inside the locker room door, and suddenly everyone in the place was grinning, too. It was as if a light had been snapped on in a dark room.

“Hey, Heinie, got any tickets?” yelled Cousy.

“Go away,” Heinsohn said.

“I need tickets, Buddy,” Cousy said.

“Well, I haven’t got any,” LeRoux said.

“Just two,” Cousy said. “What about Howie?”

Howie McHugh is the Celtics’ press agent.

“He doesn’t have any either,” LeRoux said.

“Well, there’s no point looking for him then,” Cousy said. “I’ve got to go out and find some tickets. Hi Al—”

We shook hands, and I told him I wanted to talk to him for a story. He grinned slyly. “Will you mention Camp Graylag?” he said.

“You mean that boys’ camp you run up in Pittsfield, New Hampshire?” I said.

“You know very damn well that’s what I mean,” he said. “Look, I’ve got to get those tickets. I’ll be back soon. I’ll be taking diathermy and a whirlpool bath for my various ailments, and I’ll see you then.”

He was back in 10 minutes. He took off his jacket and tie and shirt and went into LeRoux’s room. He held his right hand up, and the trainer clamped it in a black contraption that look like the two sides of a metal club.

“What are you going to do besides coach?” I said. Cousy has a three-year contract to coach the Boston College team.

“Well, I’ll be traveling some,” he said. “I’m going to continue to do public relations work, and I’ve got a couple of other things in mind—if I can find the right location, I might open a restaurant. And there’s the camp. I’ll have plenty to do.”

“Will you miss this?” I asked.

“This?” Cousy looked at his hand locked in the diathermy gadget, and grinned. “I should say not.”

“Basketball?” I said.

“I’ll still be coaching,” he said.

Bill Russell came in. “Hey,” Bill said, “you still among the half-dead?”

“Half-alive,” Cousy said.

An usher came in with a program. “Will you sign this for a sick kid?” he said. “Here’s his name.”

“Put it over there,” Cousy said, pointing with his free hand. “I’m righthanded. I’ll sign it after I get sprung from this thing.”

“Why are you quitting?” I said. “They all say you could keep going.”

“Physically, yes,” he said. “Mentally, no. I just can’t get ‘up’ the way I used to. And I’m sick to death of the traveling.”

“You’ve always traveled,” I said. “Even in the offseason.”

“Yes,” he said, “but nothing like this. We are here today, in St. Louis tomorrow, in San Francisco the next day, in Los Angeles the day after that—it goes on and on and on. That ‘Oh, Hell” trip you took with us was a junket compared to what we do now.”

We both grinned. In 1954, I traveled with Cousy on a typical NBA trip. We went to Rochester, Minneapolis, Milwaukee, St. Louis, and Fort Wayne—five cities in six days—and all the way around the circuit we played a card game called “Oh, Hell.” The rules of the game were somewhat vague, interpreted as we played by Cousy and Bill Sharman. I not only got practically no sleep on the trip, but got practically broke.

“You guys framed me,” I said.

“You just never learned how to play ‘Oh, Hell’ right,” he said.

LeRoux came and freed Bob’s hand from the diathermy machine, then said, “Go on in the whirlpool bath.”

The usher came back. “There’s a guy outside wants to see you,” he said. “Says he’s from Springfield, Illinois.”

“Bring him in,” Cousy said.

While the usher was out, Bob signed the program after first carefully copying the sick boy’s name from a slip of paper beside it. The man from Illinois entered. “Got something for you,” he said. “From the state highway patrol.”

“What is it—a ticket?” Cousy said.

The man grinned.

“No—this.”

He handed Cousy a star-shaped badge, marked “Illinois Highway Patrol.” Cousy took it and said, “Well, isn’t that nice. Thanks a lot. If I ever drive in Illinois . . .”

“Don’t drive too fast,” the man said.

While Cousy was getting ready for the whirlpool bath, I went over to talk to Russell. “Will you miss him?” I said.

“Who won’t?” Russell said.

“What’s it mean—his retiring?” I said.

“A lot,” Russell said. “A whole lot. He’s one of the all-time greats. I’ve been lucky. I’ve seen him in his prime and in his twilight years. There isn’t much difference either. Physically, he could play three, four, maybe five more years.”

“Mentally?” I said.

“That’s up to him,” he said. “He doesn’t think so. We’re going to miss him. We’re going to miss him terribly.”

I went out then and waited for the game to begin. The people packed into the Garden were buzzing with anticipation. A great roar went up as the Celtics, led by Cousy, trotted in for their warmups. Cousy took off his jacket and stood for a moment, shaking his wrists to loosen them up.

I watched him go through the familiar routine to get ready for the game. He stood in the layup line, ran in and tossed the ball through the basket. He trotted, then sped up, then tried it again, shaking his wrists all the time.

“He looks the same as ever,” I said to a Boston sportswriter.

“He shouldn’t quit,” the writer said. “He’ll be great for a long time yet.”

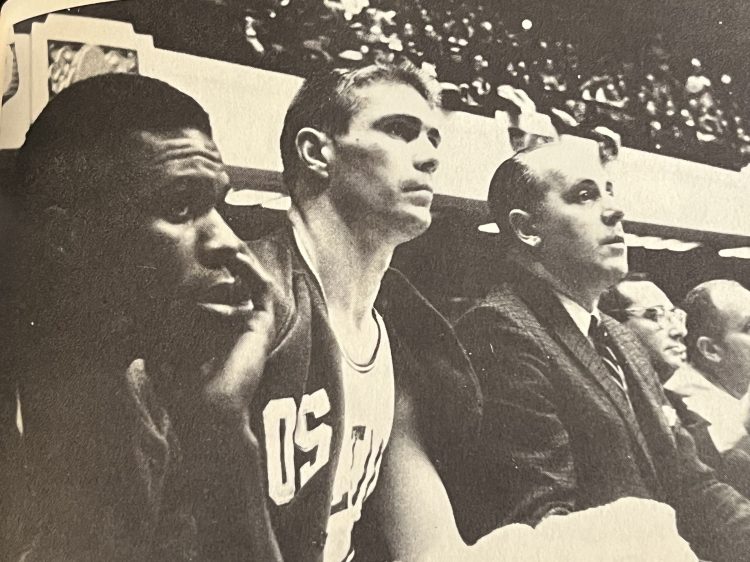

The Celtics’ starting lineup was called to the floor—Heinsohn, Sanders, Russell, Sam Jones, and, finally, Cousy. The announcement of his name brought another roar from the crowd.

The players stood at attention for the national anthem, then, with Cousy in front, went to the floor. Cousy stood, thoroughly relaxed, in the familiar position I had seen so often—hands resting on his hips, his left foot forward, his face calm, his eyes on the referee, who was walking toward midcourt with the ball.

Tom Gola of the Warriors trotted over and shook hands with Cousy. Russell stood at center opposite Wilt Chamberlain. Their hands touched, the buzzer sounded, the referee tossed the ball high in the air and the game began.

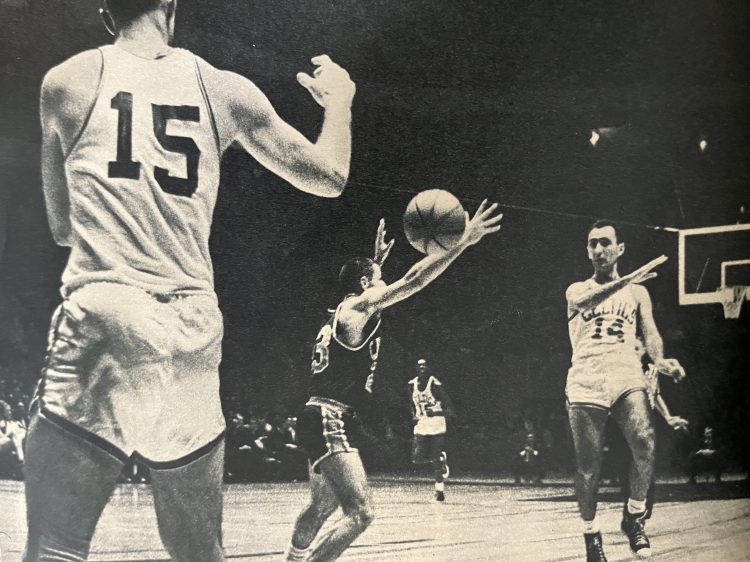

Russell beat Chamberlain to the ball and tapped it to Cousy. Bob dribbled downcourt, passed to Sam Jones, and Jones scored. Seconds later, Cousy stole the ball, passed to Jones again, and the Celtics were four points in front. Less than a minute later, Cousy again passed to Jones, who scored.

“He looks great,” I said.

“That’s the way he’s been all year,” the writer said. “He can go like that for half the game.”

The Celtics were slick, and Cousy was in the middle of most of the scoring plays. He stole the ball, he grabbed rebounds, he passed, he scored. Three times he outraced Guy Rodgers for the ball. Each time, the Celtics scored.

Near the end of the first quarter, with the Celtics six points in front, Auerbach sent in K.C. Jones for Cousy. Bob looked tired. He walked slowly off the court, wiped his face with a towel, and sank to the bench. I watched him as he took a series of deep breaths; he seemed more relaxed.

He didn’t play again until the first half was nearly over. The first thing Cousy did when he got back into the game was throw a long, beautiful pass three-quarters the length of the floor into the hands of Heinsohn, who scored a layup. A minute later, Cousy scored himself after taking a pass from rookie John Havlicek. Then Bob threw another long pass to Heinsohn, who scored again. At the half, Boston led, 62-47.

Cousy started the third period and was as brilliant as I have seen him. Another tremendous pass, from behind his own foul line, landed in Heinsohn’s arms and subsequently in the basket. Then Cousy stole the ball, twisted away from Rodgers and Gola, slipped it to Sanders, and Sanders scored. Cousy kept on passing—to Heinsohn, to Russell, to Sam Jones, to Jones again—all for baskets. When he left the game with two-and-a-half minutes of the third period remaining and the Celtics leading, 93-74, the crowd cheered.

He sat out most of the fourth quarter. He was relaxed, yet alert, for he followed every play with his eyes. Halfway through the period, the Warriors cut the Celtics’ lead to 104-91. Auerbach sent his first team back in, and Cousy set up a play for Russell, who passed to Sanders for a score. Two minutes later, the Celtics had a 20-point lead again, and Cousy left the game for good. The final score was 127-109.

In 24 minutes, Cousy had five field goals and a foul for 11 points, plus 11 assists. “A routine night for him,” the writer beside me said. “He shouldn’t quit.”

I went back to the Celtics’ locker room. “How do you feel?” I asked.

“All right,” Cousy said.

“You don’t seem to have slowed up any,” I said.

“I’m all right for 20-25 minutes,” he said. “I used to go 40-45.”

“That’s the only difference?” I said.

“The only physical difference,” he said. “But I used to love it. Now it’s a chore.”

“Any chance of your changing your mind about quitting?” I said.

“None whatever,” he said.

We shook hands, and he said, “Al, don’t forget how to spell ‘Graylag.’ G-R-A-Y-L-A-G.”

“Don’t worry,” I said. “I won’t.”

“A man makes his own shoes. Cousy made his . . . and nobody’s going to fill them—nobody—not ever.”

Satch Sanders, the young philosopher, on Bob Cousy, basketball’s master cobbler.