[For the 1990s NBA, it was the best and worst of times. The league’s talent level had never been higher, but its high-paid stars had never been so surly, rebellious, and, in some cases, downright weird. Writer Dan Dieffenbach takes up these worst of times in the following short piece that ran in the May 1995 issue of SPORT Magazine. Dieffenbach, now a noted actor and filmmaker, talks to the right people and makes all the right points. Definitely worth the read for those who loved the 1990s NBA.]

****

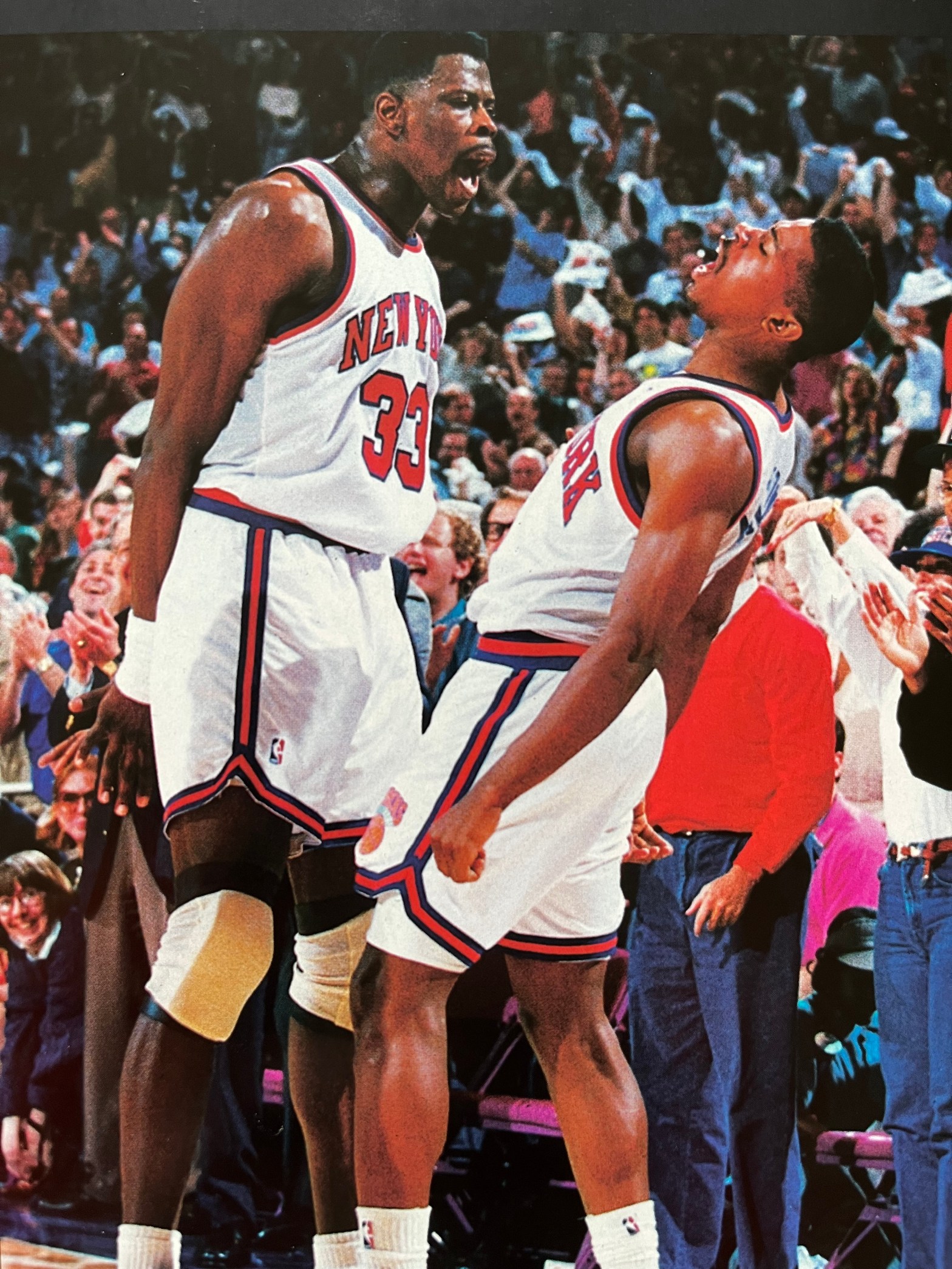

Derrick Coleman—as a rookie—once said of the New Jersey Nets, “The leader of this team is the guy who makes the most money.” Looking back, those 13 words might have been the most prophetic spoken during his tumultuous four-year career in New Jersey. On the subject, he now says, “I didn’t include coaches because they don’t make as much money as us. Coleman also invented the new NBA credo: Young superstar players have the big contracts and will fight authority. And despite what John Mellencamp says, authority doesn’t always win.

“We’re not just paid a certain amount of dollars to shut up and play basketball, we’ve got our own opinions,” Coleman said, while shaving his head before a recent game. “But no, I don’t think there’s a tug-of-war between players and coaches, and I don’t think there’s a problem at all.”

No problem? The league’s star players make more money than anyone else on the team, including head coaches (case in point: New Jersey, where Coleman will make $7.5 million this season while his coach, Butch Beard will earn $300,000) and are setting the trend of doing basically whatever the heck they want. That defiling list includes missing practices and team flights, skipping shootarounds, moaning about playing time, arguing with management, and overall insubordination.

SPORT Magazine discussed this problem with NBA players, coaches, and management, searching for the proper prescription to cure the league-wide epidemic.

****

“I hoped the game never would’ve gotten to this point, but apparently it has,” says former Golden State Warriors coach Don Nelson. “Coach-trashing is an accepted part of the business today.” These days, there seem to be plenty of I’s in “team.” Perhaps the NBA stands for the Narcissistic Basketball Association?

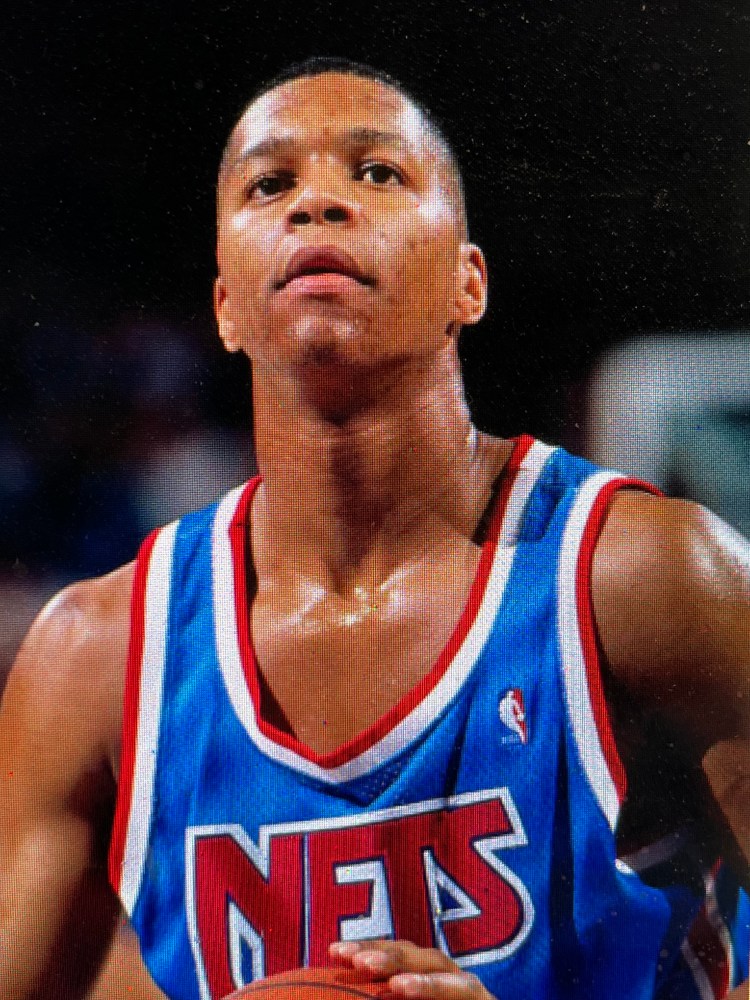

“The league has changed since I first came here,” says the Nets’ Sleepy Floyd, a 12-year NBA veteran. “The players have a lot more control and a lot more say-so in personnel decisions and a different attitude in relationships with coaches. How you handle it? I’m not sure.”

Repeat after me. Coaches coach. Players play. The unwritten rules of NBA basketball are supposed to be that simple. “Before, players didn’t really challenge coaches like they do now; players didn’t challenge authority,” says one Eastern Conference player. “It’s just a different time, a different player.”

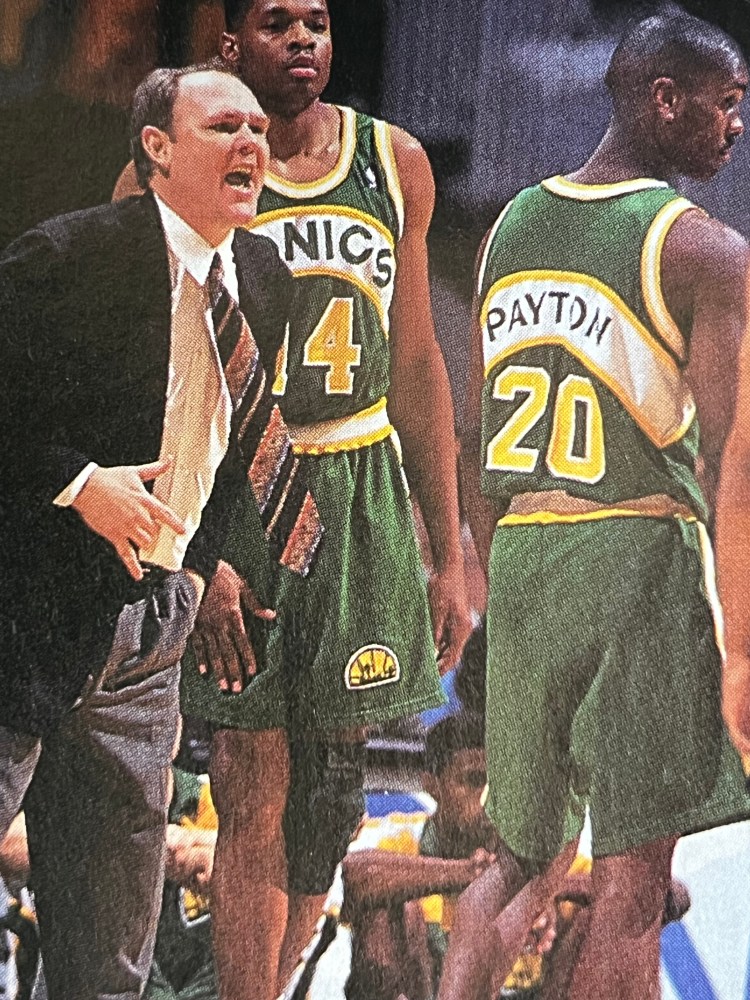

In the old days if you wore a tank top, you set picks, blocked out, and hit the open jump shot. Today, after being spoon-fed in college and built up to superstar status before setting a sneaker on an NBA floor, adolescent millionaires find listening to and following directions from suits a tough pill to swallow. “Very simply, the problems come from greed and the money that can be made in this game,” says Seattle SuperSonics coach George Karl.

Floyd agrees: “You’ve got guys coming in making so much money and thinking they know it all, and that’s not always the case.”

Coaches around the league are experiencing the bite of the behavior. “The thing about basketball in the 1990s is that you’ve got to worry about guys showing up for this and being late for that, but you’ve got to take disciplinary action to keep the team foundation,” says San Antonio Spurs coach Brian Hill, an expert on the subject after dealing with Dennis Rodman, who skips team practices and breaks rules as if they were hair appointments.

Disciplinary action had never before seen the likes of a Coleman offering a blank check for his seasonal fines or community service workers who can dunk. On national television, Charles Barkley kicks in folding chairs, Scottie Pippen throws them. And these furniture guys are the Jordan Heirs?

“I think we’re in a stage in basketball, with expansion and the success of the game, that there are some problems creeping into it which have to be addressed and understood,” says Karl. “But the future will hold solutions because the game is too strong, and I don’t foresee the bad winning over the good.”

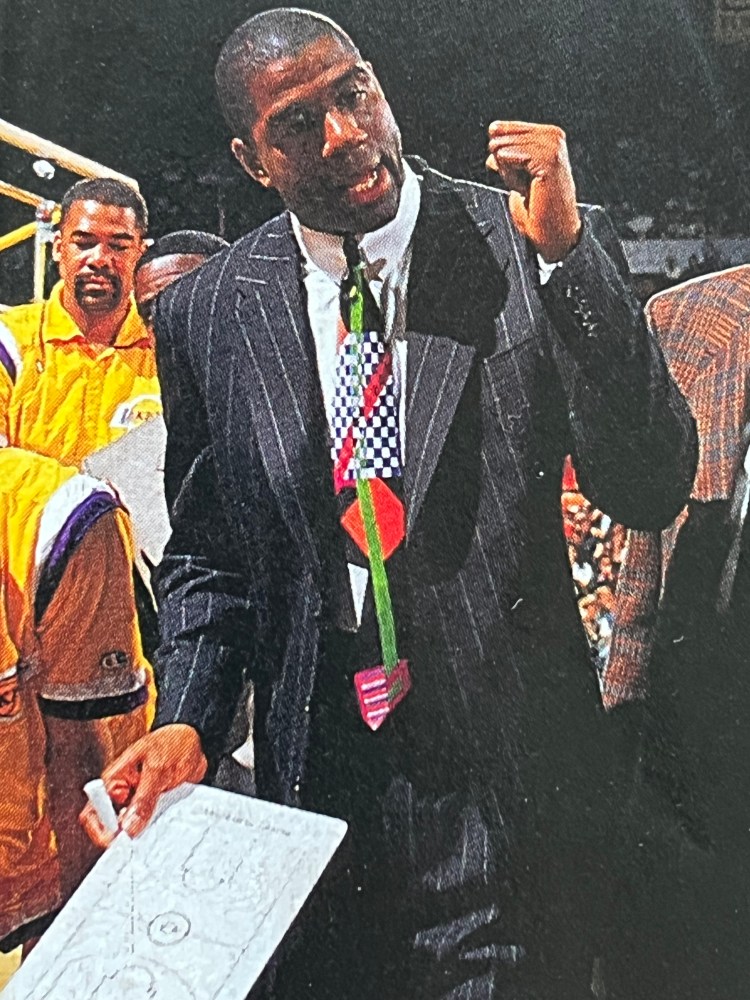

Former Laker Magic Johnson witnessed this new wave of attitude up close in a brief stint as the Lakers head coach. “We didn’t have to deal with that in my time,” he says. “Now I think because guys feel they’re making so much money, they don’t have to respect their coach or organization.”

“There’s a certain amount of professionalism that’s gonna have to be carried out with this team on and off the court,” says the Detroit Pistons’ Joe Dumars. “I told the guys, ‘Hey, listen, you represent yourself, you represent your families, and you represent the Detroit Pistons, and I really don’t think any of you want to embarrass any of that.’”

Players allegedly falling into that category, like Coleman, disagree: “I think all players respect their coaches, but guys are going to miss practice and things, it’s part of life.”

“When these guys miss a practice,” Johnson explains, “they think they’re hurting the coach, but they’re really hurting themselves. The fines really don’t mean a thing to these players, but they should. I’m talking about pride as a player, and we’ve got to get that back in our young guys.”

Magic stops and rubs his chin, searching for an answer. “It’s tough for me to understand that this new generation doesn’t care about working, they just care about how many points they score. That [attitude] made me get out of coaching.”

****

“I wouldn’t say I’m a bad boy [laughing], but maybe I’m one of these new generation players, who speak their mind, and I think a lot of people can’t deal with that,” Coleman, 27, says. “I don’t know who’s on the All-Bad-Boys team, but anybody who speaks up for themselves and doesn’t let anybody run over them would be on my team. Me and [Chris] Webber and Scottie Pippen and some other guys who speak their mind, and any player that does that around the league has my respect.”

Say uncle? It’s time to talk solutions:

—Rookie Salary Cap: NHL commissioner Gary Bettman may prove to be a genius by installing the four major sports’ first rookie salary cap at $850,000 beginning next season. “You’ve got to have a rookie cap, something to make them not miss those practices, make them work hard to get the seven, eight-million-dollar contracts,” says Johnson. “Rookies come in making more than veterans, and they think, “I don’t care about the $100 or $1,000 fine.”

—Bring Back the Player-Coach: The last one was the Boston Celtics’ Dave Cowens, who finished with a 27-41 record in 1978-79. If the authorities are questioned, put the players in their shoes for a season. Picture this: Coleman coaching for the Nets; Christian Laettner or Isiah Rider with a clipboard in Minnesota; Gary Payton or Kendall Gill discussing calls in Seattle; Dominique Wilkins designing plays in Boston; and Webber, who was almost one in Golden State, calling the shots, in Washington.

—Increase the Fines, Increase the Peace: For throwing a chair during his tantrum, Pippen was suspended one game without pay and fined $6,000 by Rod Thorn, NBA vice president of operations. “Players missed practices in the 1960s, but it was easier to threaten them because they didn’t make as much money as today’s athletes,” says Thorn. “What they’re doing with Dennis Rodman in San Antonio, suspending him for breaking rules, that’s what you have to do in certain situations.” Thorn and the NBA had the right idea in February when they slapped a lengthy suspension without pay on Houston’s Vernon Maxwell and docked him $20,000 for punching a fan in Row L at Portland.

—Grow Up: For the NBA to escape this trend, coaches and players need to mature and become responsible for their actions. “After a game or the next day, you sit down and think about it, and if you feel that you were wrong, then you say you were wrong—it’s all part of being a man,” says Coleman.

“That’s how things happen the way they did on Golden State [with Nelson and Webber],” Floyd explains. “They should’ve sat down and talked. It was a simple as ‘Where do you want to go eat?’ But nobody gave in. On one hand, you had a coach from the old school, and on the other a new-age, million-dollar player, a franchise player, and nobody gave in.”

****

“When things don’t go your way, then you see the true character of a player,” explains Dumars. “Last year, we won 20 games, and I never pouted, kicked and screamed, never ranted and raved or pointed fingers.

“We’ve all got egos,” says the Sonics’ Payton, having an unusually quiet headline season and (surprise) his best statistical season. “It’s just a matter of time before things go wrong, but the good teams can work it out over the course of a season.”

“It’s a matter of respect on both parts,” says Coleman. And respect is still practiced by a large percentage of the league’s players, true role models with names such as Dumars, Stockton, Robinson, and Price, and coaches such as [Lenny] Wilkens and [Pat] Riley.

“It appears to me and the older veteran players that there is a lack of respect for the profession itself,” says former NBA all-star and TV analyst Reggie Theus.

Pro basketball is now a game littered with offensive goal-tending. In other words, contracts enable players to tend to their own goals and get out of a situation if coaching turmoil or a losing record persists.

“Shot-blockers” have become synonymous with “agents” because agents have prevented teams from getting a shot at winning an NBA championship. Take Webber v. Nelson, for example, where the plaintiff left the Warriors in turmoil and separated himself from any possible ring-fittings for the next decade if, indeed, he remains in the nation’s capital, which he promises to do.

“I thought all the problems with Chris were in the negotiations and not on a personal level,” says Nelson. “I was joking around saying that I would quit in order for him to stay on the team. I didn’t think it had gotten that serious.”

****

Things have gotten serious. On the Pacific Coast, Karl juggles egos like chainsaws, and Nelson is hospitalized with the league-wide epidemic lackarespectitus before ultimately losing his job. In the Rockies, Dan Issel steps down due to “exhaustion.” And on the right coast, the pitfalls of New Jersey prevail. The game of basketball no longer has the same pecking order. What used to be “coaches talk, players listen” is no longer.

Companies like Nike continue to reward Rodmanesque players for rebelling. It has become vogue to commercialize and promote the problem-child athlete. “Back in 1985, when I came into the league, trash wasn’t selling, it just wasn’t selling,” explains Dumars.

It is today. And the modern NBA player has much to sell. Nearly 60 percent of the league’s players earn at least $1 million a season; only four coaches make that much. Thirty players earn at least $3 million in this the highest-paid ($1.87 million average) professional league (baseball: $1.27 million; football, $610,000).

“This is a time when you’ve got to have support from management, and those clubs that have that kind of support, if you check, will have the most successful basketball teams,” explains former Cal coach and current Portland Trail Blazers scout Lou Campanelli.

What started as rare, humorous television clips of player-coach alterations has mushroomed into daily Sports Center highlights. “Right or wrong, good or bad, the negatives have been a distraction to the good stuff that is in the game,” says Karl. “The vast lot of athletes are committed and dedicated athletes, and what bothers me most is the attitude guys take away from the good guys.”

When the facts are weighed—obviously, the wallets are in heavy favor of the players—the answer remains unclear. Jurors on the O.J. Simpson case might have an easier time finding a solution. Both parties are to blame, for somewhere down the line the coaches, the public, the media, and the management gave that single player the power.

“Finding a happy medium for younger players is not an easy thing to do,” Floyd says. Magic agrees: “Coaches’ hands are tied; it’s awfully tough to be a coach these days.”

In the NBA, at least for the time being, it is evident: The animals control the zoo.