[In his book the Pyramid Principle, former UCLA star John Vallely (1968-70) wrote about his first day on the UCLA basketball team. Lew Alcindor shook his hand, then introduced him to the rest of the guys as the transfer from nearby Orange Coast Community College:

“I shook hands with them and extended my hand to Curtis Rowe, who had a look that matched his personality: abrasive. At 6-foot-7 and 225 pounds, he was a force for opposing defenders to guard and had a great presence on the boards. I had battled Curtis in the Orange Coast vs. UCLA game and had played well enough against him to be noticed by Coach Wooden, so I knew he was well aware of me. ‘I’m John Valley.’

Curtis responded, ‘Like JV? That’s where you’ll be, man, on the JV squad.’”

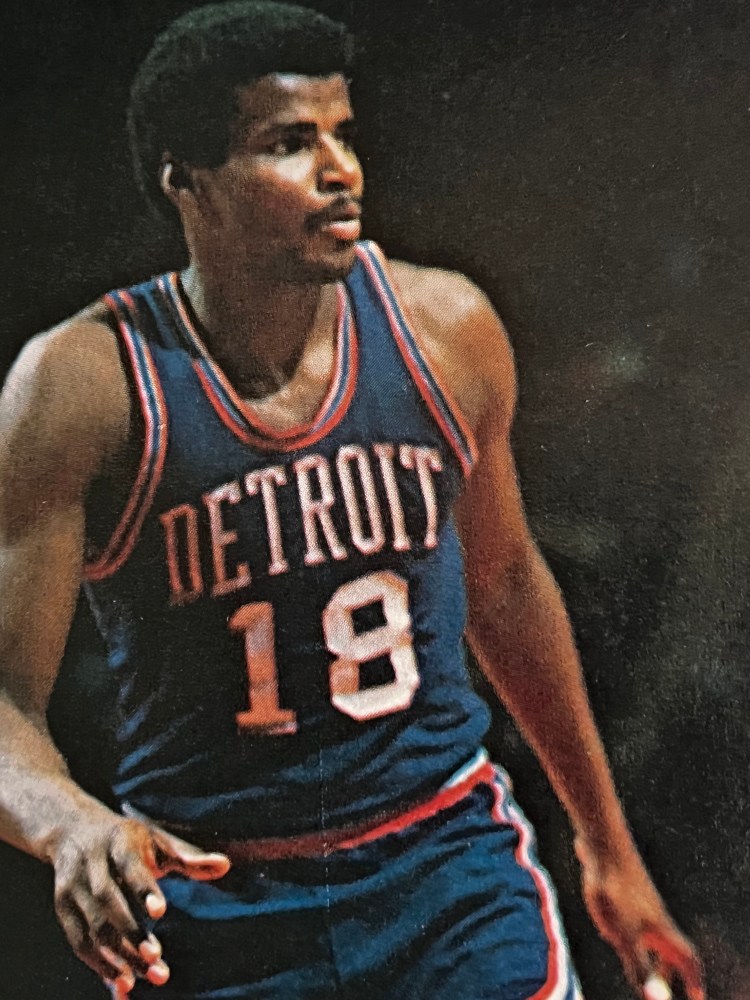

Despite the awkward hello, Vallely came to respect Rowe and his winning play. Rowe was a three-time NCAA champion, second-team All-America as a college senior, and the 11th player selected in the 1971 NBA Draft by the Detroit.

With the Pistons, Rowe was considered the perfect hustling, hard-nosed fit alongside their young center Bob Lanier and All-Pro backcourtman Dave Bing. Leon the Barber, the Pistons’ gyrating superfan, once artfully quipped of Rowe: “He can play defense like the Third Armored Division, has the durability of an oak tree, and, in a match race, he could spot a beam of light 50 yards and win in a walk.”

Rowe would spend five solid seasons in Detroit (1971-76). Then in October 1976, Rowe was traded to Boston. He claimed to be “delighted” for the chance to play for the Celtics, and his new team claimed to be thrilled to have him. “The name Curtis Rowe has been on our minds for many years,” said Boston GM Red Auerbach. “Over the years, we’ve talked of ways to get him.”

Watch out what you hope for. Rowe and his college teammate-turned-Celtic Sidney Wicks came to hate their winters in Boston and openly showed their discontent. “Come on, fellas,” Rowe infamously spoke up in the Celtic locker room, “there ain’t no W’s’ and L’s on our paychecks.” It was impolitic to say. But Rowe was being honest . . . and abrasive. That was just him.

In the following article, published on April 13, 1975 in the Detroit Free Press’ Sunday Magazine, Rowe seems happy to be a Piston and sounds professional. He also offers some telling detail about life in the 1970s NBA and the challenges of defending some its superstars. The byline belongs to Michael Steinberg, and his brief article is definitely worth the read if you enjoy the 1970s NBA.]

****

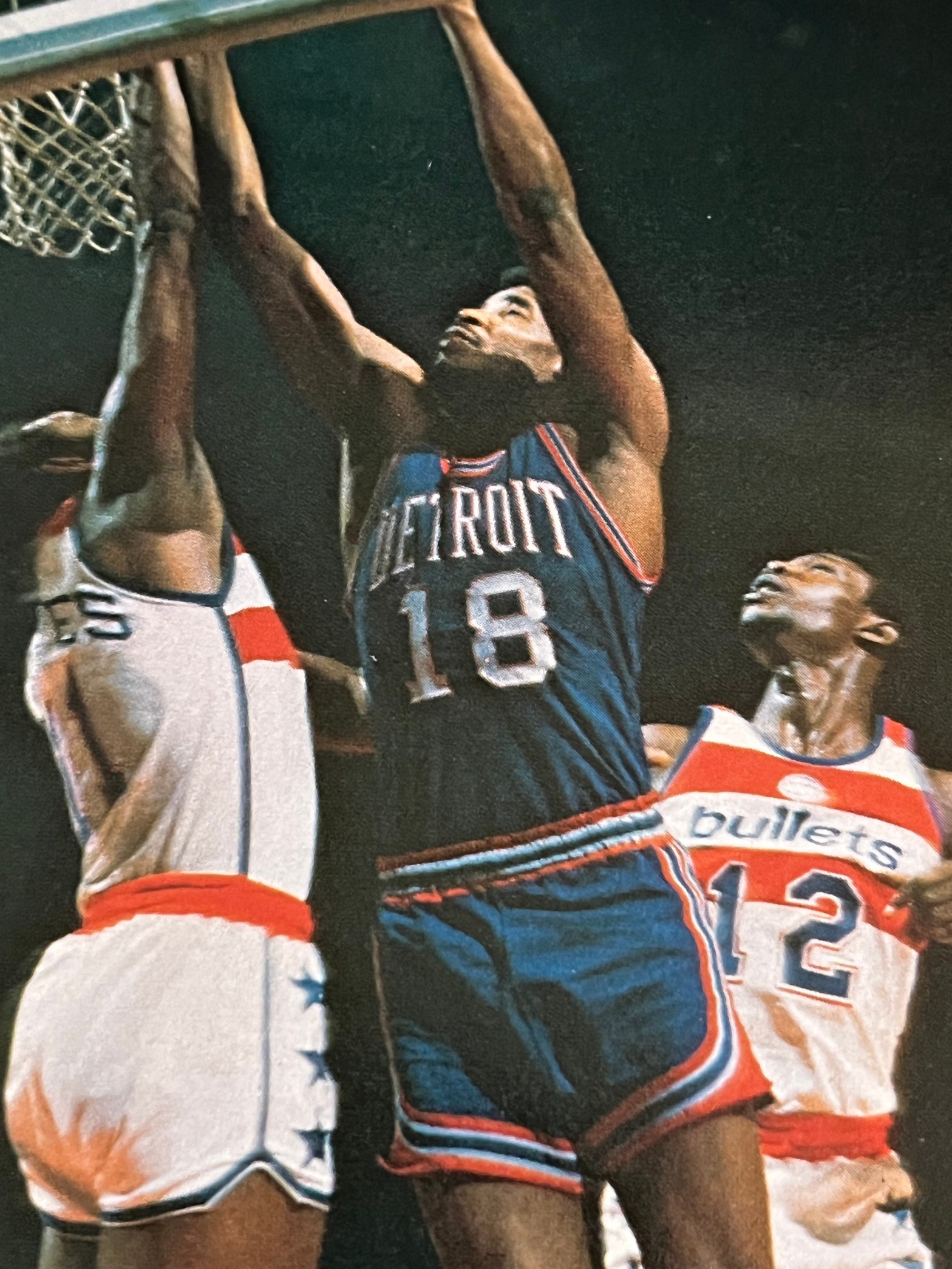

Leaping up on the defensive boards, arms extended, Curtis Rowe rebounds an errant shot and pitches the ball to Dave Bing breaking across the timeline. Maneuvering against a lone defender, Bing dribbles, head fakes, and bobs his way to his own foul line. He looks left and catches sight of Rowe coming up on the wing. Bing fakes right, draws his defender up, and whips a bounce pass across his body to the streaking Rowe, who curls the ball softly through the hoop. Two points, Detroit.

“When we’re running well and shooting, that’s my game, I like that,” says Curtis Rowe, the 6-foot-7, 225-pound former UCLA star.

“In Dave Bing, we have one of the quickest guards in the league. When he can beat his man down the floor, he’s going to create some situations where my man is going to have to pick him up, and then I can roll to the hoop and pick up a few layups or the open jumper.”

Although he prefers a wide-open offensive style, the flexible forward is prepared to play more of a pattern, or set, offense when it suits his coach’s gameplan. “I always prepare the same mentally whether we run or set up,” he says. “Everybody has a particular duty on this team.

“Basically, Coach [Ray] Scott wants me to hit both boards, play the strong defense, and get 10 to 12 points a night. When you break it down, there’s a lot more to playing a game than just what shows up in the statistics. There are so many little things, intangibles, like setting the picks, getting the ball to the hot man, or else it might be just running downcourt on a break and sacrificing myself to get someone else an easy layup or the open shot.”

Because he will be guarding a tough forward every night and also be expected to score, rebound, and execute all of those intangibles he speaks of, Rowe is conscious of his own physical condition. He often lingers after practice to get more of a workout.

“Conditioning during the season is a real problem,” he says. “When you’re on the road, it’s really hard to regulate your habits. Going through different time zones really messes up your system. You might eat at 11 a.m. and then again at 4 p.m., and the next day you’ll eat at 9 a.m. because you have to catch a plane. You might play in three different cities 500 to 1,000 miles apart on three successive nights. And you sleep at different hours depending on what city you’re in and where you’re going next. You’ve got to be in good shape physically and be alert mentally to endure that.”

After four years in the pros, Rowe has admittedly matured to the point where he functions not only as a player, but as a tactician. “Forward is the only position on the court that you have to play from endline to endline,” Rowe comments. “Centers run up and down the middle of the court, and guards run basically from free-throw line to free-throw line. And almost all offensive plays in the pros are directed at the forwards.”

Rowe is aware, therefore, that he has to be a two-way ballplayer at all times. Scoring points and getting rebounds isn’t enough. Night after night, he is faced with a challenge of going up against the premier forwards in the game, men like Spencer Haywood, Sidney Wicks, and, on occasion, Rick Barry.

“The toughest forward for me to defense is Sidney Wicks,” says the durable forward. “I’ve been playing against him, off and on, for 10 to 12 years now, and he still gives me problems. Sidney can jump straight up and go left or right with equal dexterity.”

“When I’m guarding him,” Rowe continues, “I just try to think about what he likes to do. Sidney likes to work baseline, so I try to keep him out as much as possible. You want to try and always keep him in front of you, so he doesn’t create situations with the center. With his quickness and height when he’s going to the hoop, he has a center at a big disadvantage.

“Spencer Haywood presents a different challenge,” Rowe says. “He likes to overpower you. He plays the physical game; he likes to jump over you and push and shove. The only way to defense him is to keep him from getting the ball down low. I like to stay on his right hand and keep him moving left all night and bump him every time he gets the ball.”

Having been around long enough to know, however, Rowe is realistic about his or any other defensive forward’s ability to stop the superstars. “When I first came into the league,” he recalls, “I really thought I wasn’t doing my job if I didn’t stop everyone I defensed. But I’ve learned since that you don’t worry about stopping guys like Haywood, Wicks, and Barry. They might have an off night, but they do not get stopped. No way. The thing is to contain them and concentrate on shutting off the others on the team who can hurt you. You’ve got to figure that anyone out on the floor is good and can burn you.”

At UCLA, Rowe played with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Wicks, so he never had to be a big scorer. Now with the Pistons, he knows that Dave Bing and Bob Lanier are the primary point-men. So this familiar situation doesn’t bother him.

“Sure, everybody likes to score points, but I’ve learned that if you think too much about personal goals, you’ll only get yourself in trouble. In fact, having any personal goals at all hurts you in the pros. I can remember in college if I didn’t think I was getting the ball enough, I could always say something like, ‘Hey, how about letting me see the ball,’ and they’d listen.

“But here, you can’t get away with that stuff. Everybody is good, everybody’s a pro, everybody’s getting paid. You’ve got to have something more to succeed.”

That “something more” that Rowe possesses is his adaptability, his willingness to play both ends of the floor, and his sense of perspective, both on and off the court. “No successful basketball team wins titles with just a scorer or two. My idea of how to play the game is to recognize the role Coach Scott wants me to play and go out and do it. Teamwork and sacrifice are what makes winners in this game.”