[Jalen Brunson may be the heart of the current New York Knicks. But he got his big heart and iron will to succeed from his father Rick Brunson, now his assistant coach with the Knicks. As a child, Jalen watched his father train tirelessly in the offseason to seize his next NBA opportunity, and there were many of them. The elder Brunson played for eight teams in nine NBA seasons (1997-2006). All on unguaranteed contracts, making him easily replaceable on the roster.

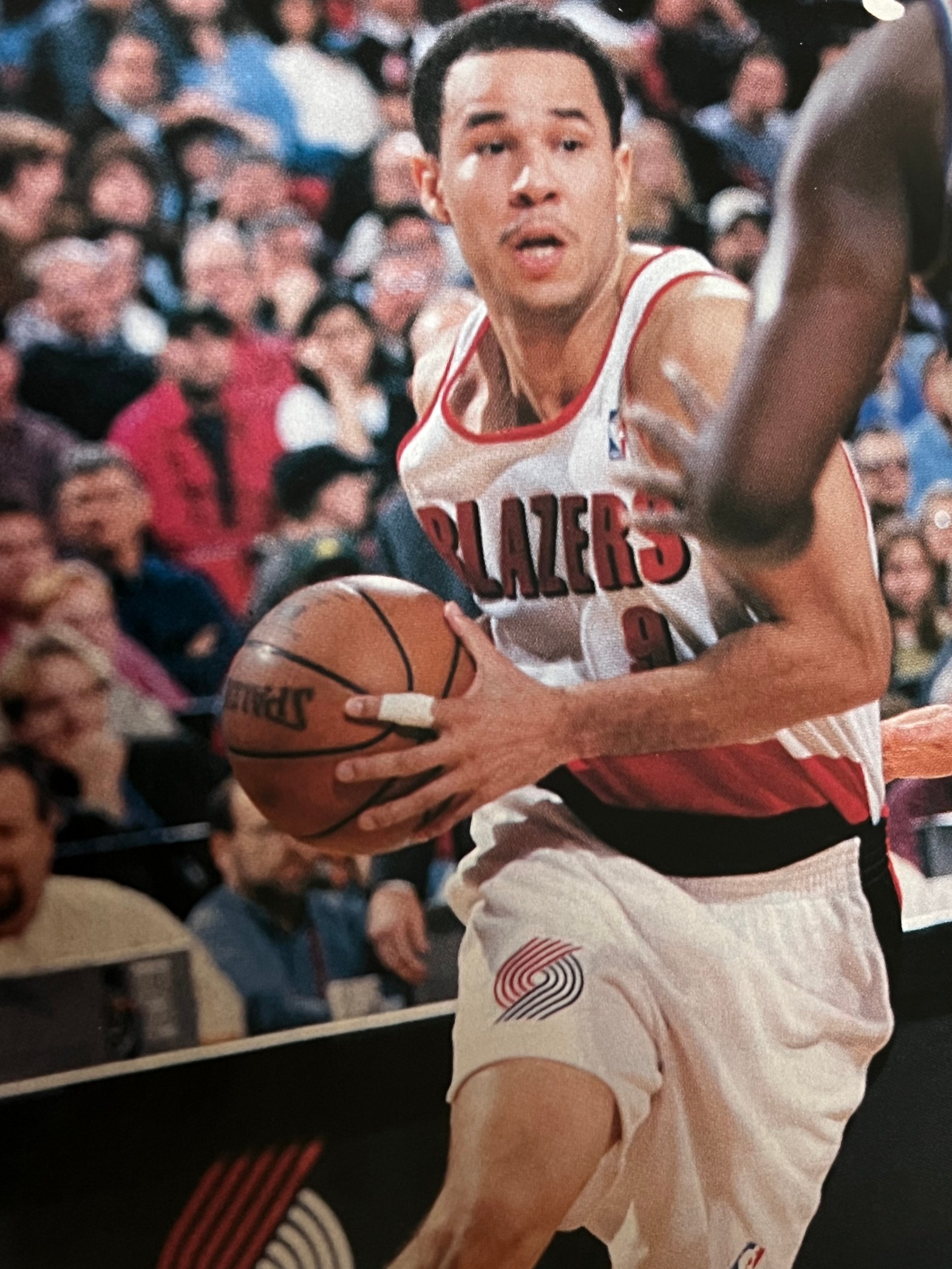

In this article, from the February 1998 issue of the magazine Rip City, journalist Matt Williams talks with Brunson about his college career and his first NBA opportunity with the Portland Trail Blazers. Brunson spent one season in the City of Roses before moving on to, you guessed it, the Knicks. If you like Jalen Brunson, you should enjoy this story.]

****

Let’s be honest. Sometimes we take NBA players for granted. Our comparisons between players, abilities, stats, and teams often accumulate and bury one simple fact: These guys are good. The best in the world at their profession.

It’s not until one here’s a story like Rick Brunson’s that those assumptions are dismantled, at least for a moment or two. But Brunson has learned to take nothing for granted. And that’s the reason he found himself in the Portland Trail Blazers locker room—and on the floor at crunch time during his second NBA game—when injuries felled Portland point guards Kenny Anderson and John Crotty early this season.

Eric Brunson (his real name) was born in Syracuse, New York, in 1972. He and his four siblings (two sisters and two brothers) were raised by his mother Nancy; Dad left the home early on. Brunson began playing basketball at a local neighborhood club to stay out of trouble and played his high school ball in Salem, Massachusetts. The sweet-shooting two-guard quickly became the pride of this small city, and the recruiting letters for the McDonald’s All-American rolled in.

“The Salem community wanted to make this big thing about recruiting, visiting all the schools in the world, and having all these guys calling me all year round, but I signed early in the recruiting season, saying, ‘This is where I’m going. Don’t recruit me,’” Brunson recalls.

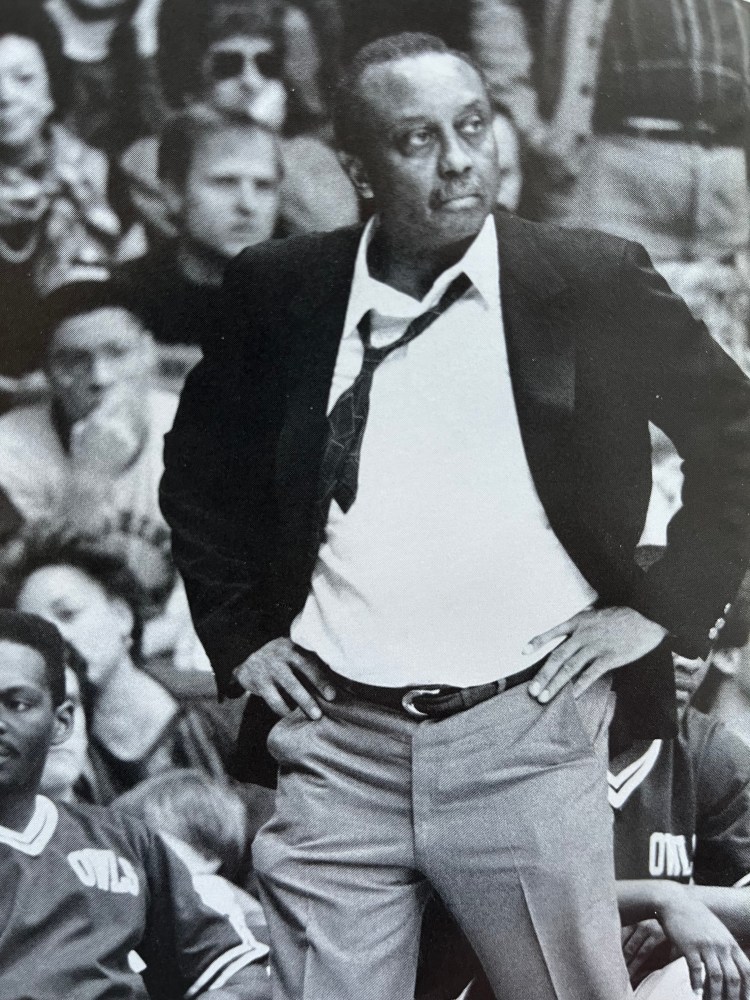

As it turned out, the teenager had been doing his own recruiting all along. Throughout high school, Brunson would drive down to Philadelphia twice a year and spend the weekend watching Temple head coach John Chaney run his Owls through grueling practices. The grouchy vet hides his love for his players behind a shield of temper and irritability and makes them work for every inch they gain. The result often is a tough, well-adjusted person and a solid basketball player.

“I just saw positives, and I needed some discipline,” says Brunson, who read Chaney’s book, Winning is an Attitude, while at Salem. “I just loved his philosophies in life and the way he raised young men.”

Interestingly, Brunson says Temple was about the only school not chasing him. “They didn’t know who I was the first two years or so,” he says. “My senior year they obviously knew who I was because I was in all the magazines, and I told him I was coming. They didn’t believe me, until I signed my letter of intent.”

Once he did, his difficult journey to the NBA began and began slowly. Brunson was consistently hyped to be the point guard successor to Temple’s Mark Macon, who had just graduated to the Denver Nuggets. But Chaney had a different view. He sat Brunson in favor of Vic Carstarphen, an older guard who had paid his dues.

“I was a hothead,” Brunson admits. “I expected to go in there and be the man, and I didn’t understand that you have to go in there and grow and learn.”

Although the Owls made it to the NCAA tournament, Brunson averaged only five points a game. He almost made a decision that, in retrospect, would have distanced him from the man who eventually would become the father he never had. Brunson considered transferring home to Boston College but realized that leaving town would be the easy way out.

After much deliberation, he decided to return. Walking into Chaney’s office, the coach wore his trademark scowl. But Brunson all but got on his knees, and Chaney accepted his penance and brought him back into the fold. “He respected it big time, me going in and saying that I need to be here, that I want to come back,” Brunson says.

What a decision it was. The next season, Brunson was named the most-improved player in the Philadelphia Big Five. Along with former Blazers guard Aaron McKie, now with the 76ers, and Lakers guard Eddie Jones, Brunson led his Owls into the NCAA tournament and to the Elite Eight. Brunson played 80 minutes with only one turnover in Temple’s final two games of the tournament, netting the Player of the Game award with a 21-point, nine-assist, three-steal game against Michigan in a fourth-round loss.

The point guard was named team captain the next two seasons, serving as the team’s heart and soul while Jones and McKie flourished as its stars. There’s little doubt in his mind that his time at Temple molded him into the person he is today.

“That’s the difference between there and a lot of universities,” Brunson says. “[At other schools] you go there, you play for your coach, then you don’t talk to him anymore. This is more than basketball, this is a friendship for life, for everybody.”

He’s still considers Jones and McKie among his best friends and called the latter immediately after McKie was traded home to the 76ers in December. But there’s one man who clearly stands above everyone.

“Coach is my best friend, my father figure,” Brunson says. Chaney’s grating style and irreverent policies were tough to accept initially, but Brunson took the blows and reaped the rewards. “All that stuff you see on TV, you have to go to practice and really watch it,” he says. “I’ve seen him make people cry. He’ll challenge you to a fight, he’s a crazy dude.

“But it’s not like he’s disrespecting your manhood, your person. He yells at the things that you’re doing. You have got to understand how to separate it, and I learned that. It took me a year and a half to do it, but once you do, it makes you mentally strong. Without him, I wouldn’t be here mentally.”

It was the mental strength that delivered Brunson from the City of Brotherly Love to One Center Court in Portland. Brunson wasn’t surprised when he wasn’t selected in the 1995 draft. He wasn’t expecting to be. The summer prior to his senior season, Jones and McKie were drafted 10th and 17th, respectively. He had one more season at Temple, where he sacrificed his numbers, at coaches wishes, in order to bring along the crop of young players who filled the void of Jones’ and McKie’s departure.

He watched the draft but admits he wasn’t ready for the NBA. “You have got to know, you can’t be an idiot about it,” Brunson says. “Some guys get caught up in it, but if they haven’t talked about you all year, they’re not going to talk about you that day.”

So began a mental overhaul in order to achieve his NBA dream. It was a necessary mix of patience and realism. Brunson knew he wasn’t ready for the Continental Basketball Association (CBA) either and spent the 1995-96 season playing the Adelaide 36ers in Australia gaining his confidence and finding his marks.

“My senior year, I was at 218 pounds,” says Brunson, who now weighs in at about 195. “So I got in shape over there, played with a great coach, and came back. When I came back, I was ready for the CBA.”

Brunson played the 1996-97 season with the Quad City Thunder, but again didn’t expect to be wooed by the sirens of the NBA. “I didn’t want a call-up last year,” he says. “You have got to understand, it’s a process. You don’t want to get up there and then get labeled: This kid can’t play. Once you get that on you . . . I planned on being there the whole year.”

This season was different. Playing for the Connecticut Pride, Brunson told his wife Sandra, that he soon was going to be called up. “I said ‘I’m out of here.’ I knew I was out of there, and look what happened.” When the Blazers called, Brunson was tied for first in the CBA averaging 23.9 points per game, third with 6.6 assists, and ninth with 2.0 steals.

The chance to shine came sooner than expected. Running over basketball’s second-tier was one thing, but playing 18 minutes against the Pacific Division-leading Los Angeles Lakers is something else. In just his second game in the NBA, Brunson found himself on the floor in crunch time and was sent to the free-throw line with 19.4 seconds left, his new team up 100-97.

He missed the first free throw, then hit the second. Exactly 8.2 seconds later, he was there again. Swished them both. “I was in situations like that in college,” he says. “Coach put you in situations where he wants you to fail and sees how you respond to it. That’s the way Coach raised me. Hitting free throws? That was simple.”

“He did a terrific job,” says his latest coach, Portland’s Mike Dunleavy. “He’s got a good IQ, a good feel, he’s a smart player so he picks stuff up very quickly and knows how to play the point guard spot. He’s a very solid player, and he came out of a real solid program.”

But is he an NBA player? “I think so,” Dunleavy says.

Says Brunson: “My thing is, like in high school, I want to be the best high school player I can be so I can play at the Division I level. And everything else that falls in the middle is a plus.

“[In the CBA] there’s a lot of people who don’t look at reality. Those guys never leave. You have to spend time, you have to evaluate yourself. You have to be honest. I said, ‘OK, I’m going to the CBA.’ After college, I didn’t get drafted, so it’s a process. Am I focused and doing it? I know I am. I’m self-motivated, so I’m going to do it like this.”

The sparkle of putting on a pro uniform wore off on Brunson soon after his arrival in Portland. He’s learned not to take it for granted. “It was a great relief, and when I got here, I was all excited at first. But now it’s like I have another goal. I want to play in this league. I want to be here, I want to be a contributor. Maybe I want to be the starter. The stuff that falls in between is a bonus.?