[In 1997, the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame published its 100 Greatest Basketball Players of All Time. Numbered among them was the great David Thompson, of whom writer Alex Sachare wrote: “He was the Skywalker, a player of dazzling skills who blazed across the horizon like a comet before crashing in flames.”

Nicely, but sadly, said. Thompson was a phenomenal talent, and most basketball nuts age 60 and older still have a favorite David Thompson story or two, either from his college days at North Carolina State or the start of his pro career in Denver.

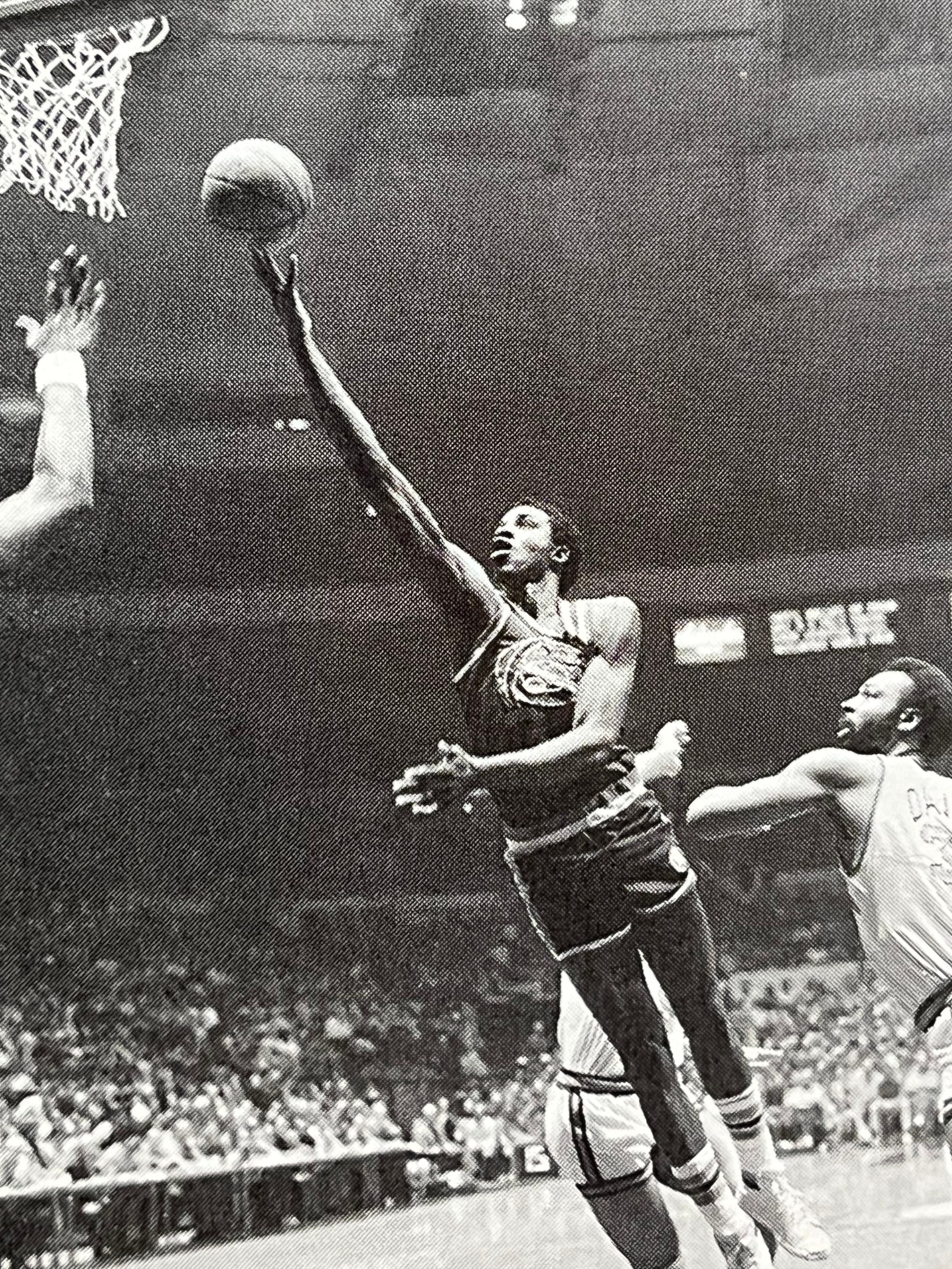

Thompson, though a tad under 6-foot-4, was one of the modern game’s seminal high-fliers, not quite on par with Julius Erving but literally right up there with him. Among his pro exploits, Thompson averaged 26 points per game as a rookie in 1976 and led the Nuggets to the ABA finals. The next season, Thompson followed the Nuggets into the NBA and led the former ABA’ers to the Midwest Division title as one of the NBA’s top scorers. For his stellar play, Thompson was rewarded with one of the then-richest contracts in pro basketball.

As noted in the following article, published in the December 1980 issue of the magazine All-Star Sports, the big contract and its great expectations wore heavily on the shy, mild-mannered Thompson. Just how heavily often is overshadowed today in the rush to mention Thompson’s other battles. The big one being cocaine addiction, not yet reported in this article. It would lead in 1984 to his famous, under-the-influence stumble down the stairs of New York’s fashionable Studio 54, which left Thompson badly injured and brought an abrupt end to his pro career. “I had the talent to be one of the greatest basketball players in the history of the game,” Thompson later rued, “and I blew it.”

Telling this cautionary tale of a young star and his big contract is sportswriter Barry Wilner, who has covered just about everything during his phenomenal career with the Associated Press. He also published some outstanding books, including one that he co-authordd on the NCAA basketball tournament titled, The Big Dance.]

****

They used to say these kind of things about David Thompson: “Inch for inch, the best player in basketball.” “The kind of guy you build a franchise around.” “Worth every penny that he makes.”

Now, the descriptions tend to be somewhat different: “A headcase. He can’t make up his mind if he wants to earn his keep or just collect it.” “A terrible waste of talent.” “A sorehead and complainer. If he concentrated on playing instead of bitching, he’d be the same player he used to be.”

The Jekyll-Hyde existence of David Thompson is one of the mysteries of sport. When he is good, Thompson is among the best performers ever to take a basketball court. When he is bad, he is the worst thing you can say about an athlete—a loser. And, at $800,000 a year yet, making “David Skywalker” one of the five highest-paid practitioners of roundball.

His big-number contract is one of the problems most bothering Thompson, according to Denver Nuggets general manager Carl Scheer. “I think that the pressure of the contract and personal problems have hurt him the most,” said Scheer, who negotiated the five-year deal with Thompson. “When we come to town, all we hear is, ‘David Thompson, $800,000.’”

Things have gone sour for the Nuggets and Thompson almost from the day he signed that lucrative pact. There was little doubt that the former All-American at North Carolina State and two-time College Player of the Year, who led the Wolfpack to the 1974 NCAA title, was worth a lot of money.

But, as Larry Brown, Thompson’s coach with the Nuggets until midway through the 1978-79 campaign, said in one of his more honest moments. “I told management that if they jeopardized the franchise by signing David for an outrageous amount, they were crazy. A 6-3 ½ guy doesn’t win championships.”

Still, Thompson seemed worth the investment. He brought out the fans, he was exciting, and Denver was winning. In his rookie year with the Nuggets during the 1975-76 (Denver’s last ABA season), David was the league’s Rookie of the Year. He averaged 26 points and 6.3 rebounds, while shooting 52 percent from the field and appearing in all of the club’s games. The next season, Denver’s first in the NBA, Thompson led the Nuggets to a divisional title and a six-game playoff loss to Portland, the eventual NBA titlist. He hit for 25.9 points per game that season.

David was a force. Despite his in-between height, he was comfortable underneath the boards with the big boys. He could go with the little guys. He was the prototype small forward who had just as much effectiveness at guard.

Thompson’s third season was his best offensively, and Brown noticed an improvement in his defense. He scored 27.2 points a game, scoring 73 points in the season finale, just missing the NBA scoring title to George Gervin.

“The thing that excites me about David,” Brown said then, “is that he has done the things necessary to make better players of those around him. He was always able to score, but now he’s finding the open man and getting points for other players.

“And I’ve seen him working as hard on the other end of the floor. He wants to make himself into a top defensive player, too. To really appreciate David, you have to watch him every night. Then you realize how much he can do on physical ability alone.”

Then came the historic contract and, soon after, the problems. Injuries started to nag at Thompson. He wasn’t getting along with his teammates as well as before. He certainly wasn’t getting along with Brown, who, in turn, was having problems with team management.

For one, Brown disapproved of Thompson’s contract. For another, he was appalled when his favorite player—and a fellow North Carolina alumnus—Bobby Jones was dealt to Philadelphia for George McGinnis.

The split between the two began to widen as Brown started berating David through the press. Even before Brown resigned in February, his relations with almost everyone around him, especially with Thompson, had deteriorated beyond repair. “I was working hard, but I always had Larry on my back,” Thompson said. “He’d let things build up, then explode and catch you unaware. You’d get along great for a little while, but there always would be a time when Larry found something. He had this thing about power.

“If I came in late, he thought it was because of him, that I wanted to spite him. The next day, I’d read in the papers that my lateness caused problems. But to whom? To Larry, maybe.”

Basketball wasn’t fun for Thompson anymore. He got hassled about the big contract, especially in cities where local stars seemed just as worthy of 800 Gs a year and weren’t close to that.

Denver’s choice as Brown’s replacement, Donnie Walsh, hasn’t gotten much more production out of Thomson. Walsh, a close friend and aide to Brown with the Nuggets, is cut from the same mold as Brown.

Last season, Denver lost its first seven games and never got back in the hunt for a playoff spot. The Nuggets went from 47-35 and in the playoffs to a disastrous 30-52 record, 19 games out of first place in the Midwest Division. McGinnis didn’t fit in and was traded to Indiana. Thompson missed much of the season with injuries, including a January mishap that caused strained ligaments in the left foot and cost him about a month.

Worst of all, Thompson became a problem child. Where once people talked of how well he’d adjusted to the pros, now they just shook their heads.

At the outset of the 1979-80 season, Thomson began complaining about the treatment he got from officials. He thought the refs were “out to get me,” and that he was being picked on. The more he complained, the more he seemed to get in hot water with the refs. It went so far that the Nuggets asked the NBA to look into the situation.

“I think the refs do have it in for David,” said Walsh. “I’ve made the statement before: I don’t think David Thompson gets treated fairly by the officials. I reported it, I told the NBA supervisor (Norm Drucker) about it,” the coach reported.

“Suddenly, I saw an improvement in how he was treated. But it didn’t last long. I don’t think Dr. J or Larry Bird or George Gervin get treated this way. None of the other stars do. I don’t know why, and I’d like to know. He’s a great kid, a fine representative for the league. He’s unhappy, and I don’t blame him.”

As Thompson’s production fell, his attitude also plummeted. He wasn’t used to adversity on the basketball court, where from high school right through to the pros, things have gone his way. It may have been natural for him to strike out at someone. Rather than blame his coach, his teammates, himself, Thompson laid it on the referees.

“The refs got David off to a bad start,” Walsh said in defense of his star. “With the team losing, there’s a lot of pressure on him.”

Scheer also defended Thompson. “He blames the officials. Well, it’s a tough game to officiate,” said Scheer, whose position with the Nuggets is much more secure than Thompson’s right now. “But I know one thing. The fans come to see these guys perform, and there’s something inherently wrong in a system that prevents the fans from seeing the players they want to see.”

Drucker took offense at the Nuggets’ complaints. “The referees would like to see every ballplayer be great every night, and that includes David. The best thing for him to do is forget about the referees and play ball.”

Unfortunately, according to Thompson, that is precisely what the whistle-toters aren’t allowing him to do. “I’m either in foul trouble or getting kicked out,” he noted. “I get hit a lot and don’t go to the line. When I go to the basket, I get butchered and don’t get fair treatment from them (the referees).”

“There’s nothing I can change. I’m going to keep on playing the same way I have been. But when I go to the basket, I want to get the call.”

Despite such protestations, Thompson did not play the same game as always. Walsh, especially, noticed it. “I think David is hiding behind his problems,” said Walsh. “He’s got all the ability in the world. There’s no reason for him to be making excuses. He has to forget about the referees and go out there and play basketball. He’s got to look within himself now.

“If he’s going to make it back to the superstar status, he’s got to do it himself. I think he will. I think he’ll grow into one of the best players in the history of this league.”

First, however, Thompson must grow up. Oddly, his personality seems to have a regressed from a rookie wise and skilled beyond his experience to a veteran with a streak of green in him.

No one could have foreseen Thompson’s present problems, had they followed his career at NC State, then with the Nuggets of his first three seasons. It was Thompson more than anyone who was responsible for the Wolfpack ending UCLA’s reign of terror in 1974.

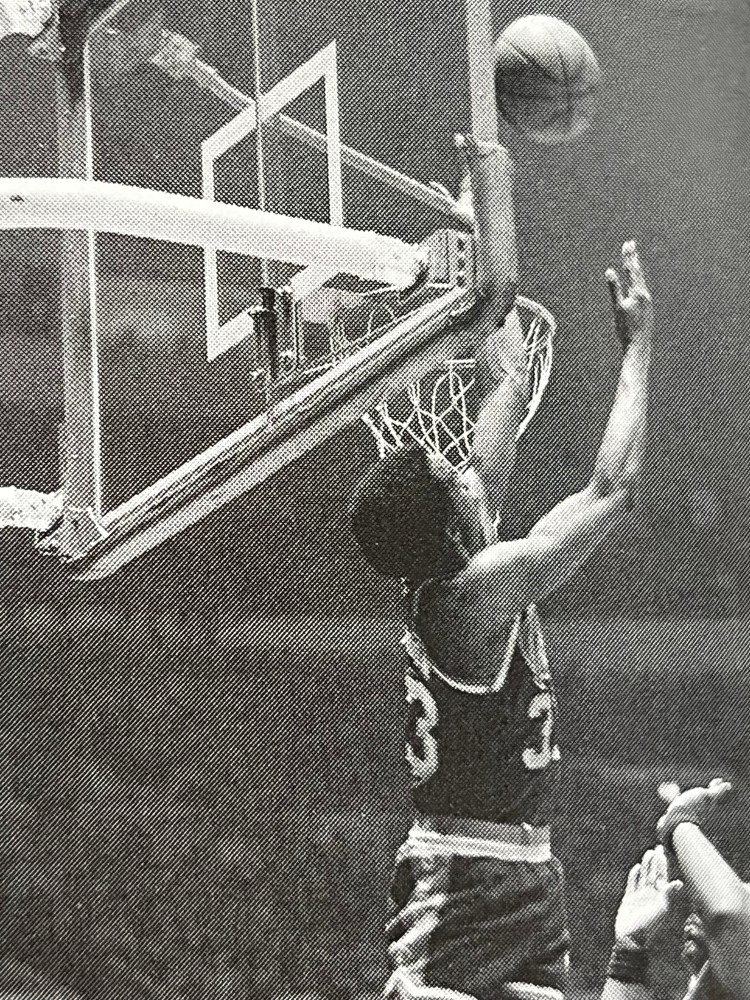

While at NC State, Thompson seemed to create a whole new basketball position: airborne forward. More often than not, he was spotted flying somewhere in the vicinity of the top of the backboard, awaiting Monte Towe’s lob passes, then ducking low-flying birds to dunk the ball—or rather, gently deposit it in the bucket, since dunking was a forbidden fruit in the colleges then.

Exhibiting his leaping ability (a 44-inch vertical jump), a deft touch from outside, and moves equal to that of any pro, Thompson was the most exciting thing to hit the college scene in years. In fact, since freshmen weren’t eligible in his first year at State, Thompson’s freshman exploits on the rookie team at NC State were as widely heralded as Bill Walton’s were at UCLA.

When Thompson graduated in 1975, both the ABA and the NBA were hot to get him. The Atlanta Hawks, then in the pre-Ted Turner/Hubie Brown years, selected him No. 1 in the NBA grab bag. The Virginia Squires chose him No. 1 in the other league.

Virginia, with little money and no chance of signing Thompson (even though playing for the Squires meant playing in the next state north from his Carolina home), traded the rights to David for three players. It was then up to the progressive Nuggets to outbid the frugal Hawks for Thompson’s services.

Denver didn’t have much trouble doing so, signing Thompson to a five-year pact estimated at $500,000 a year. Thompson’s agent, Larry Fleisher, who also serves as head of the NBA Players Association, had a clause included in the agreement: David could skip the last two seasons of the pact if he sought to, becoming a free agent.

Before allowing that to happen, Scheer and Co. assaulted Thompson with dollars. When those dollars reached 4 million for five years, Thompson agreed to play like “Rocky Mountain High” personified.

But that high has lost its altitude. One reason appears to be a switch from forward to guard, a move Thompson at first applauded. “I like it, it’s a challenge,” he said. “It gives me an incentive to go out and try harder to prove I can play guard.

“It’s a different role, handling the ball and setting up the offense. My job now is to get the ball to the other guys where they can score. Before I could set myself up, but now I have to think about setting up everyone else.

“A guard has to think about the way things are going, who is getting the ball when, who is hitting the boards. That doesn’t come spontaneously. It’s like a new game.”

It hasn’t turned out to be a good game for Thompson. He gets less chance to use his soaring skills down low. Instead, he’s expected to bomb from downtown. Nor has Thompson been as effective driving the lane. Perhaps it’s lack of interest. Maybe he isn’t quick enough to beat defenders the same way he could as a forward.

One unique offshoot of Thompson’s contract is the effect it has had on the players who guard him. Dennis Johnson of Seattle, for instance, used his defensive work against the highly paid Thompson as a leverage device in his own contract negotiations.

“Guys go out and try to stop David because they can say to their management, ‘Hey, I outplayed a guy making $800,000 a year. Where’s some for me?’” says one non-Nugget.

“I have to adjust to the way players play me,” said Thompson. “That’s a fact of life. It may not be right, but it is that way, and I’m not going to spend any sleepless night’s over it.

“I can’t beat the establishment, so I’ll do the best I can. After a while, it got sort of discouraging, and my attitude must have suffered. It got to the point where I wasn’t doing myself or the team any good, and I let it bother me. Now, I just erase it from my mind.”

In the end, then, Thompson realizes his recent faults and, this season being a crucial one for him and the Nuggets, David will try to work out those troubles. “At critical times in games, I felt like I was holding myself back. Things wouldn’t work out, and I had no confidence to set them right,” he noted.

“I do what I’m asked to do, but something is missing. I’ve got a long way to go towards being the player I feel like ought to be.”