[Phil Jackson, the NBA coaching great, of course enoyed a long career in the league as a player, primarily as a reserve power forward for the New York Knicks (1967-78). As a Knickerbocker, Jackson did the dirty work inside, and he did so in relative anonymity. That was just fine with Jackson. He wasn’t a star, and he wasn’t interested in media acclaim and its intrusiveness.

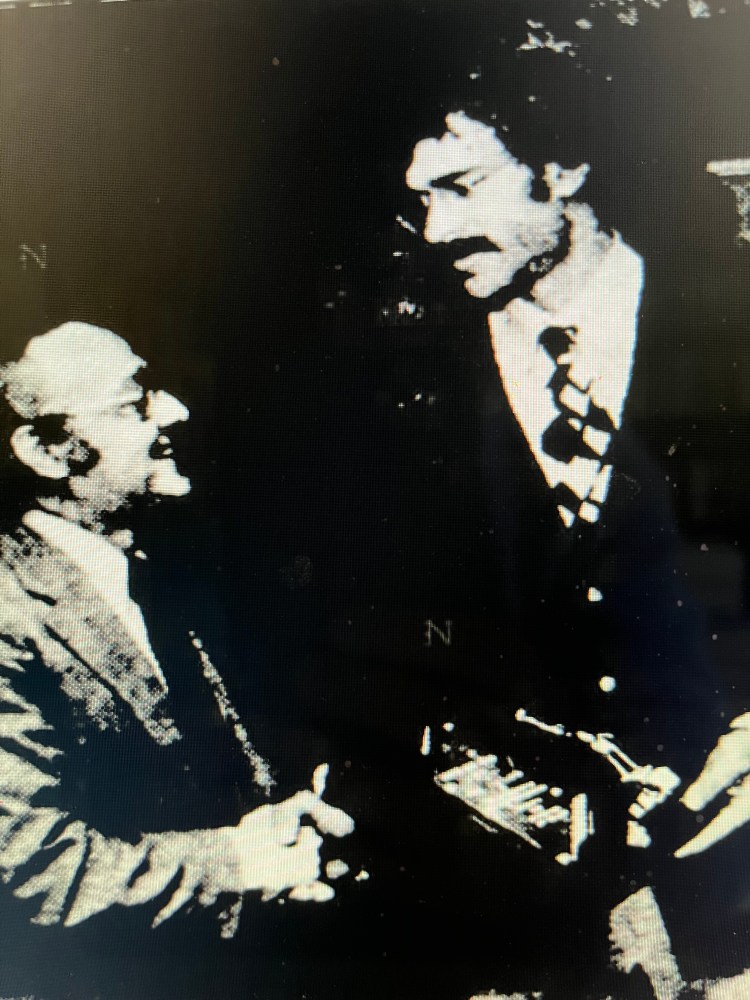

But in June 1973, the New York clothier Sy Syms (“an educated consumer is my best customer”) had a brilliant marketing idea. Syms considered himself to be New York’s unsung “whiz kid” of the clothing industry for ingeniously offering consumers deep discounts on name-brand apparel. To promote his “don’t get no respect” image and connect it to the wildly popular Knicks, Syms awarded the first Unsung Hero Award to Phil Jackson.

What follows is a brief article about Jackson accepting the award. The text, with a few gentle edits, mostly comes from the great Leonard Lewin’s article in the January 1974 issue of Basketball Digest. Just guessing that Lewin originally wrote the piece for the New York Post, and it landed after the fact in Basketball Digest. But the Basketball Digest version ends abruptly, smacking of the old editorial trick of cutting stories from the bottom (need two inches gone, just cut from the bottom). Because the abrupt cut and ending didn’t work for me, I’ve added a proper wrap to the story from wire service accounts of the event.]

****

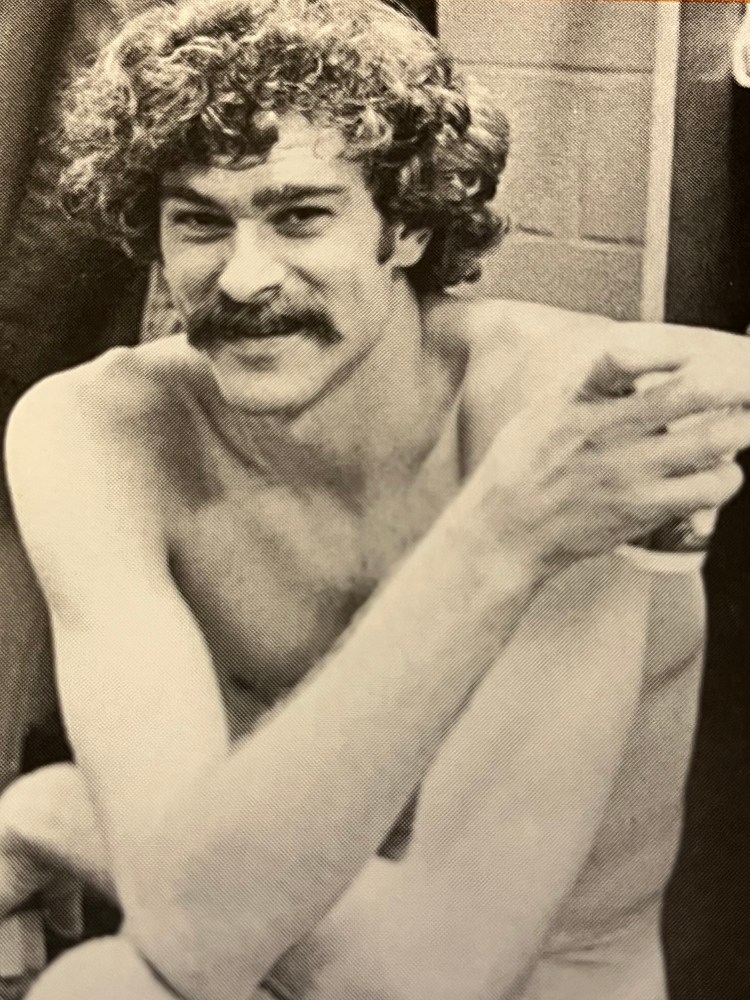

Phil Jackson, the unsung hero, sat signing autographs for those who attended his luncheon at Manhattan’s Jimmy’s Restaurant. It was the first time in all his years as a Knick that he had gained true recognition as a player.

A gentleman named Sy Syms, who prides himself as the unsung hero of the men’s clothing business, had discovered an emotional and business similarity with Jackson and decided to present Jackson with a handsome plaque, titled the Unsung Hero Award, and a $500 check for what he had done in the NBA playoffs.

A young lady with long black hair in braids walked over and asked Jackson for his autograph. “My boyfriend would kill me,” she said to Phil, “if I didn’t get your autograph.” He signed. “It’s the first time I ever heard of that,” he said, accustomed to having people ask for autographs for their kids.

It’s the first time for a lot of things for Jackson. He’s been with the Knicks six years, and he’s more accustomed to abuse than adulation.

He has remained on the sidelines and watched the sports fanaticism of New York inundate everyone but him. In 1969-70, when the Knicks won the first title, he was out for the season because of spinal fusion and was not a participant in the excitement that exploded when the Lakers were beaten.

Eddie Donovan, Knicks general manager until he quit just before the championship, saw to it that Jackson was rewarded, at least monetarily with a full share of the playoff earnings, though he never played a second that season. Jackson appreciated that. He also appreciated the excitement that New York seems to generate for the athletes that wear its uniforms.

“What’s great about New York,” he said, “is also destroying for me. The people are aggressive. They come up and say, ‘You stink.’ When I first came to New York, I didn’t realize what a professional athlete meant around here.”

He found out. As soon as he put on the Knick uniform, which he honored by making the All- Rookie team, the kids in town recognized him immediately. They chased him into the subways for his autograph.

This was a strange feeling for a young man who grew up in Montana and played his college basketball in North Dakota. “I was very much frightened by it,” he confessed.

He found it difficult to handle. “I very much like Bill Bradley’s philosophy,” he explained. Dollar Bill somehow manages to insulate himself. He escapes from the basketball excitement as soon as he walks out of the arena. Nothing tempts or traps him. He has turned down a half million dollars or more in endorsements and business deals because he does not want to get involved.

Jackson never really had Bradley’s problems for obvious reasons. Until this season, no one ever offered Phil a commercial. It never really bothered him. “I’ve never been on an ego trip,” he said. “I’ve always been able to control that. You can’t give people all that time, anyway. It’s a draining thing.”

He preferred to hide in a crowd if possible. But there’s something about Jackson that makes it impossible. The way he plays basketball is just too conspicuous. He has the kind of awkwardness that deceives the untrained eye.

It was difficult for most people to appreciate what he was doing because his fouls were so obvious and his moves so uncoordinated. He was a real Sad Sack, and he had the uncanny knack for furthering that image with everything he did.

Jackson moved to a one-bedroom apartment on W. 19th St., for example, with the idea of hiding. He wanted peace and quiet and the opportunity to walk the blighted streets of this mostly depressed neighborhood without being harassed for being a New York Knick. “I’d kinda sneak around,” he said. “But the people started to notice me. They’d follow my car. They’d stand on the sidewalk and wait for me to come out and talk basketball with them.”

It got worse around January, when New Yorkers are through with pro football and turn to pro basketball. It got even worse when Jackson began playing more late in the season. He pinpointed Dave DeBusschere’s hip injury in a game with the Baltimore Bullets in College Park, Mary. as the thing that triggered his emergence as an exciting Knick.

“It was a good event for me,” he recalled. “Dave took it easy the last two weeks of the season, and I got to play. It was very productive for me. I got in shape for the playoffs. Red (Holzman) saw it. He guarded it and moved it along.”

In the playoffs, Jackson averaged 8.7 unsung points a game, seeing more playing time as a sub than the heralded Jerry Lucas. Only the five regulars played and scored more.

Back at Jimmy’s Restaurant, Jackson posed for photographs wearing a necktie publicly for the first time in almost a year. Away from Madison Square Garden, most photographs of the 6-foot-9 Jackson showed him riding his bike around Manhattan in jeans, lumberjack shirts, and work boots.

“It doesn’t make much sense,” Jackson philosophized about today’s event, “for an unsung hero to come here and be ‘sung.’ The idea just makes me crack up. But I’ll accept the award for whatever sense it makes.”

Meanwhile, clothier Syms eyed Jackson’s coat-hanger shoulders and quipped, “He wears a 16 ½ shirt with a 40-inch sleeve.” The walls around him were decorated with poster-sized photos of Jackson modeling several suits on sale in Syms’ store.

“Gee, I’d like to get some of these,” Jackson said of the photos. “I didn’t realize they took that many pictures of me.”