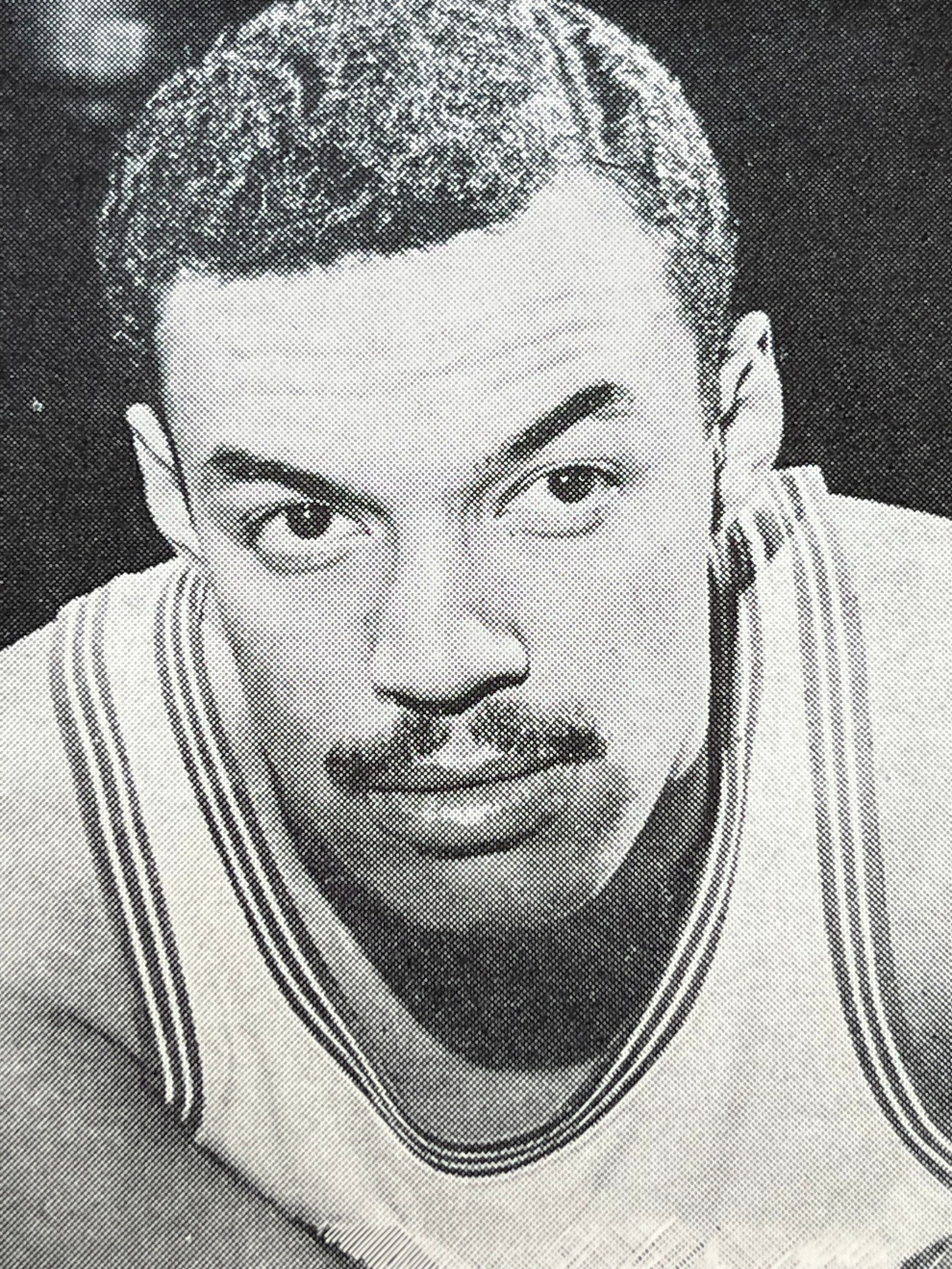

[Sonny Dove was no dove on the basketball court. He was a hawk hunting baskets as a high-scoring collegian at St. John’s (1964-67). The Detroit Pistons took Dove fourth overall in the 1967 NBA draft (Baltimore toyed with selecting the 6-foot-7 Dove, not Earl Monroe, second overall). “I’m not gonna go cheap,” Dove announced after the draft. “If they don’t pay me what I’m worth, then I won’t play. I have pride.”

The Pistons signed Dove, reportedly for $125,000 over three years, then realized they had a problem. As a Detroit reporter put it bluntly, Dove “isn’t ready to play in the NBA. His moves are stilted, and he has trouble getting off his shots against the more-experienced players.” Dove spent two seasons bouncing between the NBA’s version of the minor leagues and brief stints with the Pistons. In early October 1969, the Pistons waived Dove with one year ($40,000) left on his contract.

By late October 1969, Dove signed with the ABA’s New York Nets. He was back home, and the Nets were willing to give him a chance. “Dove can rebound, he is fast, and he will give us outside shooting,” said Nets coach York Larese. “That’s all I’m asking.”

And that’s what the Nets got.

But pro basketball wasn’t for Dove. He had other professional ambitions, and, after a decent two-year run in the ABA, the Nets cut him in November 1971. “I knew that I didn’t have much of a future with the Nets,” said Dove, who’d squabbled with Lou Carnesecca, the Nets’ coach and GM. “So, I asked Mr. Carnesecca if they would give me my release.”

Jerry Izenberg, the great columnist with the Newark Star-Ledger (who is still going strong in 2026), picks up the narrative from there. He details the good, the bad, and a very tragic. Izenberg’s story, syndicated by the Newhouse News Service, appeared across the nation in February 1983.]

*****

It was a magic time in a magic city. They formed a remarkable army, marching across the vast concrete stretches of a New York summer to the staccato beat of a bouncing basketball against a hundred carbon-copy playgrounds.

Somehow, at some point during their odyssey, they always managed to converge on Reis Park. The courts were directly opposite old Floyd Bennett Field, and they were a beacon calling out to the city’s Young Turks to test themselves against the best of their peers—who themselves formed what might have been arguably the best in the country.

These were the adolescent basketball courts of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. But they also were the testing grounds for other young men, whose names conjured up a mystique all their own in New York’s high school gyms . . . names that included kids like Willie Walters at Bishop Loughlin and Valentine Reid at LaSalle.

And then there was Sonny.

His square name was Lloyd Dove, but even the cops who fished his body out of the icy Gowanus Canal the other night couldn’t make a connection until somebody replaced the “Lloyd” with “Sonny” for them. Then everyone knew who he was.

Sonny Dove was special. He was special on the basketball court . . . a 6-foot-7 forward, who substituted finesse for muscle and touch for strength and who played with his head and his instincts about as well as anyone ever played at St. John’s University, which is saying a hell of a lot right there. But to the people who knew him off the court, he was special, too.

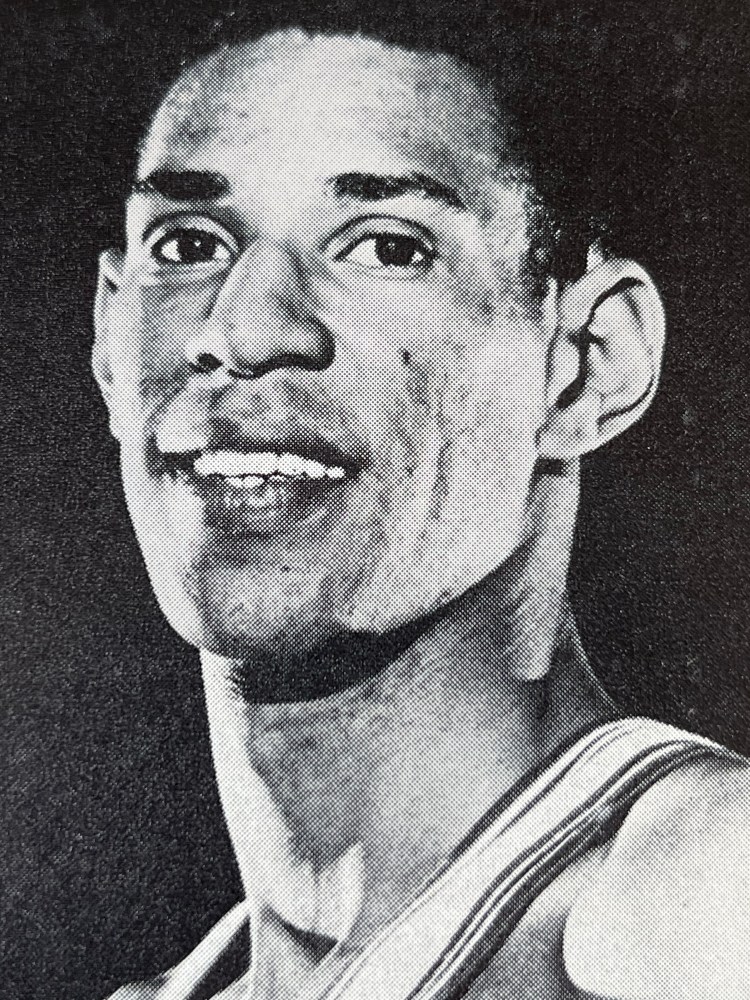

“He was,” said Lou Carnesecca, who coached him for two years at St. John’s and then for a season with the Nets in the old ABA, “a New Yor ballplayer. He played at St. Francis Prep, where I recruited him, and before that in the St. Albans CYO. He had the smarts. He could go backdoor. He had the touch. He took us to two tournaments, and the year before I took over, he took Joe Lapchick’s last team to both the Holiday Festival and NIT titles.

“He could do so many things on the floor, but I think I remember him best away from the games,” Carnesecca said. “He was one of the nicest kids I have ever known. And I would like to make sure you tell everyone that after his five years in the pros, he came back to St. John’s and got his degree.

“He felt he needed it to do what he wanted to do in life, which was to be a sportscaster, and he didn’t think he was in on a pass. He came back for the degree because Sonny Dove was a kid who believed in paying his dues.”

He was something special during those basketball years with St. John’s. People talk about the way nobody ever beat Syracuse up at that concrete coffin they used to call Manley Field House. But Sonny took his team up there and put together a textbook performance and, when it was over, the St. John’s students who had come released something like 50 white doves.

Nobody had to tell them who had made the victory possible and, if truth be told, nobody had to tell the janitor the next day he was cleaning up what is left underneath when doves fly above. Later that year, he made All-American.

The pro game never was his thing. His career was adequate, but he never fooled himself. He knew what he wanted to do with his life, and he was determined to develop those skills in the same fashion that he developed his skills on the court during teenaged summers. He was a rare kind of person, because he knew that life holds very few shortcuts.

About six years ago, a man named Carmen Calzonetti was visiting his in-laws down in Florida when he happened to catch the news on WINK-TV in Naples. The guy doing the sports looked very familiar. He should have. All during his sophomore year, Calzonetti was feeding him the ball.

“I called the station,” Calzonetti, who now works in the athletic department at St. John’s, recalled Monday, “and the first thing he asked me was if I had plans for the next night. When I told him I was free, he said he’d drive down to Fort Myers to pick me up.

“The next night, we were in a high school gym, and I was playing with him in this league which had mostly high school kids. None of them knew him except as a television reporter. So, I was 20 pounds heavier and he had some gray in his hair, and here I was feeding him the ball again.

“I’ll never forget it. There was like a flash when time stood still. I gave him the ball, and he was at the baseline, maybe 10 feet from the basket. And then he turned and popped that same jumper he used to pop, and it just floated through. For a second, it was like we’d never been away.”

Sonny Dove and a friend applied to purchase an FM radio station in Florida. FCC approval is time-consuming. In order not to waste his dues-paying process while he was waiting, Sonny Dove came home. He got himself a job doing color commentary for St. John’s basketball broadcasts. He considered it all a part of his educational process.

But it was not enough to sustain him. To supplement his income, he drove a hack at night. “Lloyd, what do you need it for?” Carnesecca asked him a few weeks ago. “It’s dangerous. A guy could rip you off and blow you away.”

“Don’t worry, Coach” Sonny Dove said. “I really like it. It gives me time to speak to people. To find out what they are thinking. It’s like another part of my education.”

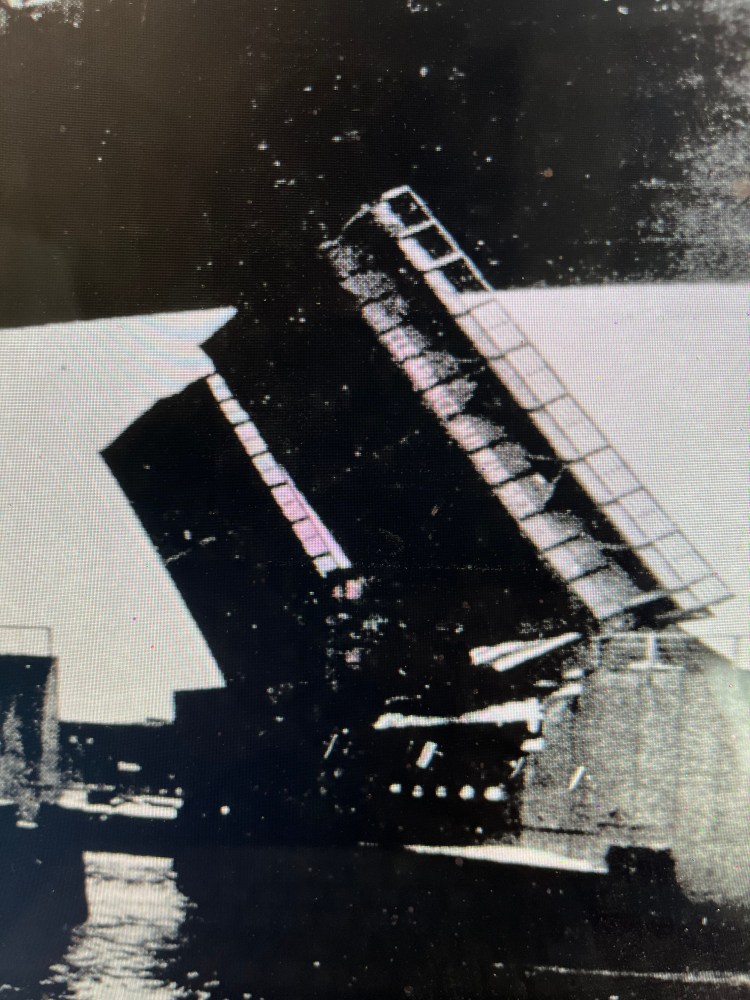

On Sunday, around 9:30 p.m., he was approaching the Hamilton Avenue Drawbridge over the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn. He was alone in the cab. He had no way of knowing that both the signal lights and the warning gate were broken. In the miserable driving conditions, he could not see the man with the lantern trying to halt traffic.

The hack plunged into 15 feet of icy water.

He never had a chance.

He was 37 years old.

A lot of people will miss him for a long, long time.

[A little on the accident from Milton Richman, then with UPI.]

“ . . . Scuba divers from the Police Department’s Harbor Unit went down into the icy waters of Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal and pulled him out Sunday night. The taxi cab he was driving had plunged through a drawbridge that was open to let a ship pass through. The bridge’s protective gate was not working. A flagman with a lantern was trying to stop traffic, but does apparently did not see him.

Dove tried to apply his brakes when he realized the span wasn’t completely down, but his cab skidded off the bridge into about 25 feet of water. He was declared dead at Long Island Hospital at 3 a.m.

Dove did not own the cab he was driving simply because he couldn’t afford it. He was working out of Pop’s Cab Corp. in Brooklyn and booking about $100 a day. With the paralyzing blizzard, blanketed the city with 20 inches of snow over the weekend, Dove might’ve kept his cab in the garage, except for a radio appeal which he heard. It was made by Teddy Ippolito, president of the Associated Radio Meter Taxi Owners Council.

“This is directed at any cab driver who can move his cab,” Ippolito said. “Please get it on the streets and help the people in this snow emergency.”

Dove heard the appeal and went for his cab.

****

[ADDENDUM: Let’s end with a brief article that highlights Dove during his ABA days. The article is pulled from a New York Nets’ program printed during the 1970-71 season. No byline.]

“Used to be,” Walt Simon was saying, “you’d come to the first workout, look around and see who was there, and say to yourself, ‘No way he’s going to make it. Or him, Or him.’ And you knew you had it made.’”

The only original Net who remained on the Nets roster this summer, Simon was speaking of his first three years in the ABA. “Now,” he said at St. Paul’s, where the team was getting ready for this season, “we have seen legitimate contenders for the forward position.”

Les Hunter, another holdover and a forward as well, had also been in the ABA since its inception, and he, too, recognized the challenge. “I think I can help them,” he said, “but I’ll be rough. It just shows you how far this league has advanced.”

Sonny Dove said nothing. He looked around him, remembered how he once got lost in the crowd when he played for the NBA Pistons for two years, stepped onto the court, and went to work. Among those contenders were two newcomers, who seemed most likely to start, namely, Rick Barry, who had proven himself a superstar in both leagues, and high-priced rookie Jim Ard, a 6-8 strongboy who can rebound and would be a perfect match for Barry on the frontline.

Dove said: “At first, you say Rick Barry is going to get all the glory and all the headlines, but, when you get your head, you realize it’s more important to be a part of a winning team. With a healthy Barry, it’s no contest in our division. We can take it all. And Jim’s worth every dime they gave him. I think he can develop into one of the best rebounders in this league. They can help our team, and that’s what counts.”

Dove didn’t come to that conclusion, easily, however. Just before training camp opened, Sonny was playing with some local pros back at his alma mater, St. John’s, when a kid cried out to him, “Rick Barry’s coming. What’re you gonna do now?”

Dove recalls Cazzie Russell sidled up to him and said, “Don’t worry about it. All you do is the best you can.”

That helped set Sonny straight, he says. “Here’s a guy,” he said of Russell, “I consider to be one of the best in the NBA, and he often has to sit on the bench with the Knicks, and it’s one of the reasons they were such a great team. And that’s what I’m doing: As best as I can.”

As it turned out, Barry was bothered by a foot injury all during the exhibition tour and into the early weeks of the regular season, and Coach Lou Carnesecca thought it best to bring Ard along slowly. (“I don’t want to throw him to the wolves,” Carnesecca said.)

Simon and Hunter were sent away in separate deals to the Kentucky Colonels, and Dove, doing the best he could, was averaging better than 20 points a game and pulling down more than his share of rebounds (“Sonny has to go to the boards if he’s going to be the other forward,” Carnesecca had said at camp.)

Carnesecca, who coached Sonny at St. John’s where he was an All-America, believes Dove’s concentration on the game is coming back, and that with work on his ballhandling, the 24-year-old Brooklyn ballplayer can be a star in this league.

“Mr. Carnesecca had more to do with me playing pro ball,” said Sonny recently, “than anybody else. I was at St. Francis Prep when he recruited me for St. John’s, and he’s the reason I went there.

“I had no aspirations about playing pro ball. I only liked to play ball because I was tall and could run fast. But he told me I could be a pro player someday. I’m glad we’re back together again. We understand one another, and I want to help this man, whichever way I can, to win a championship in this league.”