[As many are aware, Soul Power: The Legend of the American Basketball Association is now out on Prime. I haven’t watched any of its four installments and probably won’t join Prime to do so. Nothing against the documentary. I wish it all the commercial success in the world.

But, for my taste, video has its inherent limitations as streaming images squeezed into a time-limited narrative. Call me biased, but the best medium of information remains print. Obviously, my latest book, Balls of Confusion, is as detailed and informative as it gets on the ABA and its origins. The book also weaves in the all-important NBA angle, and, just as you can’t understand the Cold War by reading about the Soviet Union only, you need to cover both leagues—ABA and NBA—to understand this seminal era in pro basketball history. From what I understand, Soul Power focuses only on the ABA, and that’s too bad.

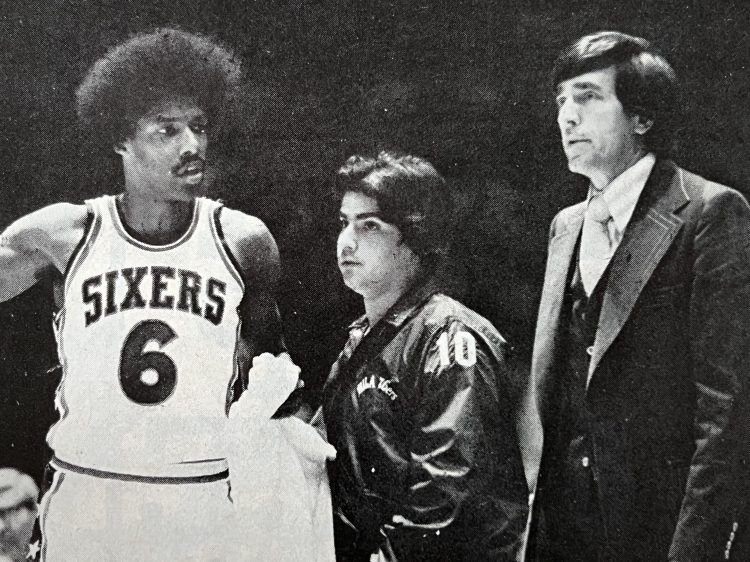

Anyway, to mark the current online buzz about of Soul Power, here’s an article about ABA great Julius Erving setting up shop in the NBA with Philadelphia. The poetic Dick Schaap is at the typewriter, and his moment in NBA time was published in the February 1977 issue of SPORT Magazine. Enjoy!]

****

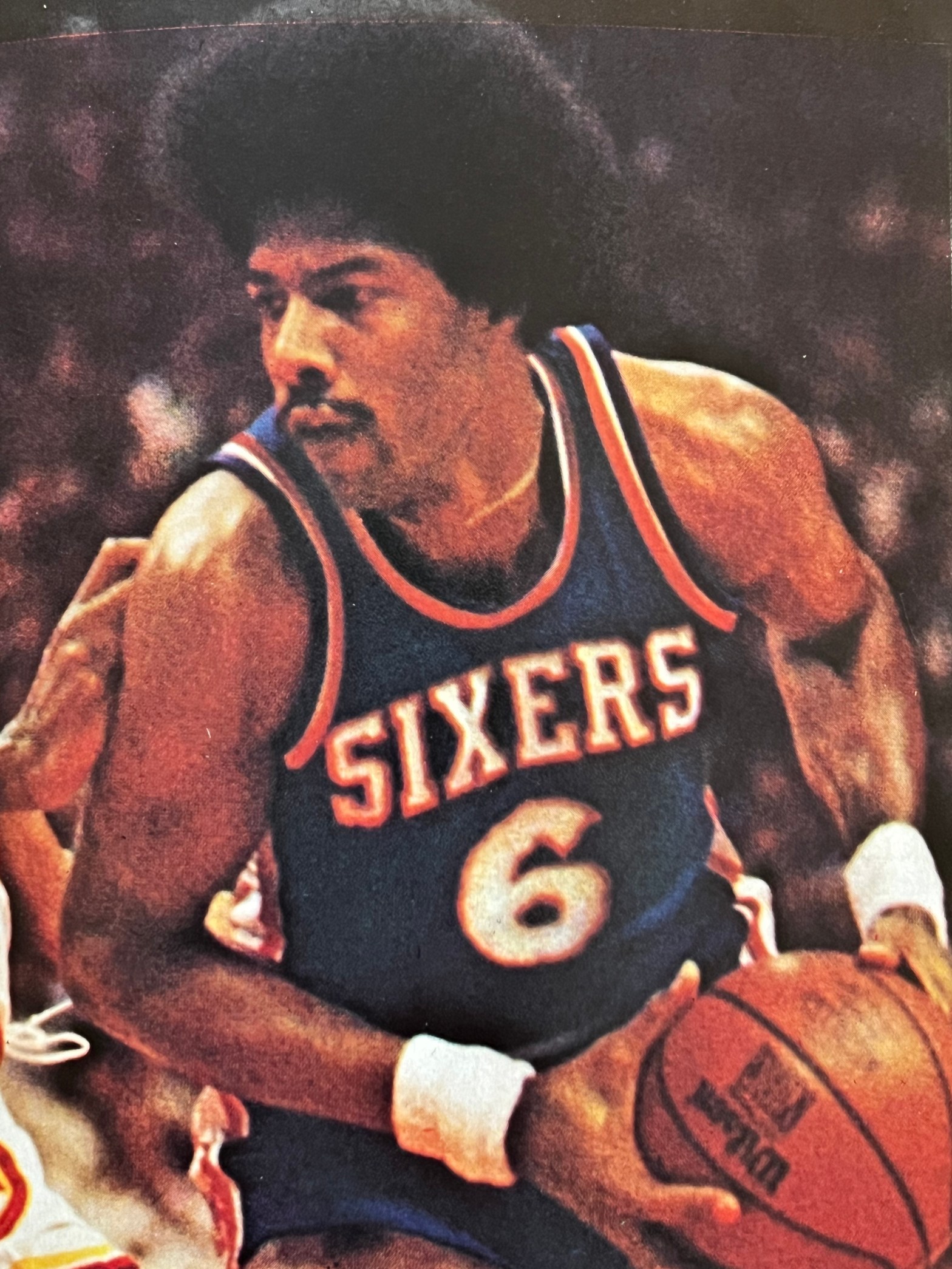

If he were the only gynecologist in a nation of pregnant women, The Doctor could not have been under greater pressure. He found his way from the New Jersey Turnpike across the Walt Whitman Bridge to The Spectrum in South Philadelphia, he had slipped into a new uniform in a new locker room, and he had been introduced to his new teammates on the Philadelphia 76ers.

Now, on the opening night of the 76ers’ National Basketball Association season, he stood by the foul circle, his name echoing through the darkened arena, a solitary spotlight dancing on his face and more than 17,000 spectators standing and cheering, their ovation exploding for two full minutes, their roar half tribute and half demand: A demand that The Doctor go out and prove, immediately, that he was worth $6 million.

So he went out on the court and, without ever having practiced with the 76ers, without having participated in a single preseason workout with any professional team in 1976, with his tender knees not properly conditioned and his shooting eye not finally tuned, out of shape and out of touch, falling back on the last resort of raw ability.

The Doctor played for 16 minutes and scored 17 points. He scored 11 of those points in the final quarter, and two of them came, with 10:30 to play, on the first dunk of The Doctor’s NBA career. With that one move, an awesome stuff that hinted of broken rims and shattered psyches, The Doctor won the crowd. He had, as he said afterward, “gutsed it out.”

****

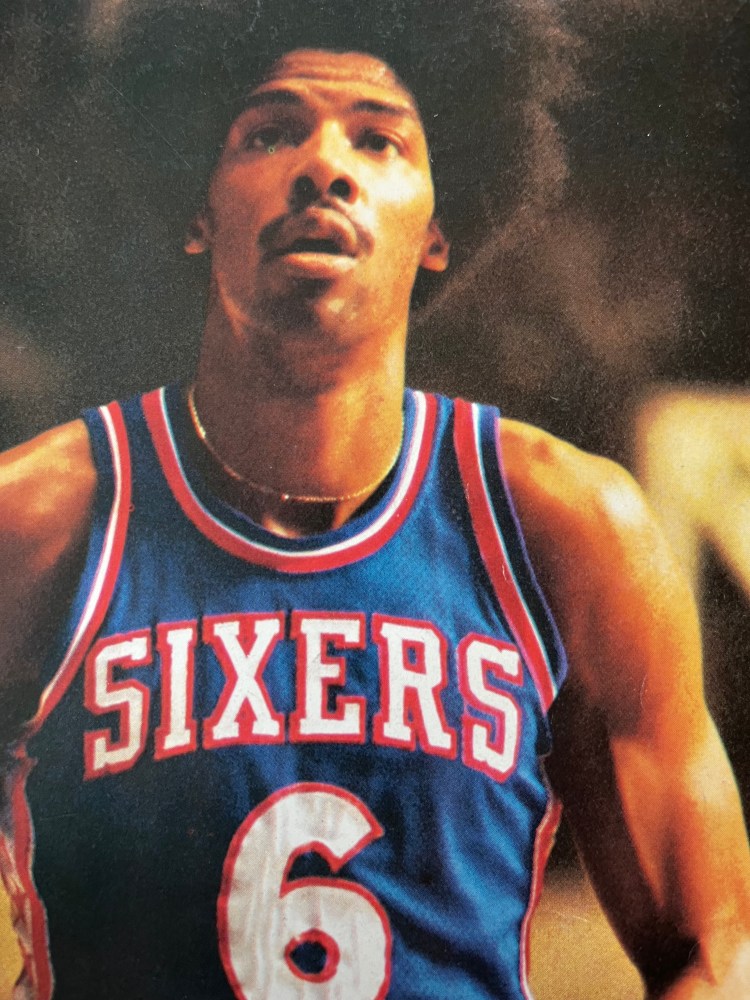

More than a month had passed since Dr. J had become a 76er. After a slow start, after a period of adjustment, Philadelphia had begun winning regularly. The Doctor had moved into the starting lineup, and now he was at home in the locker room of The Spectrum, at home with his teammates.

“Hey, Doc,” said George McGinnis, as the 76ers’ dressed for the game against the Boston Celtics. “You hear what Sidney’s saying?”

“No,” said Erving. “What’s Sidney saying?”

“Sidney’s saying, ‘I want The Doc. I want The Doc.’”

“Yeah,” said Erving. “Sidney’s saying that? No fooling!”

The Doctor smiled. Sidney Wicks of the Celtics, 6-foot-9 and strong and swift, was challenging him, and The Doctor welcomed the challenge. “You can’t let it all hang out every night, “ Erving likes to say; he insists that he conserves his skills and stresses consistency, but he admits that once in a while, when there is a special occasion, perhaps a personal challenge, he enjoys rising to the occasion and forcing his adrenaline to flow a little faster.

McGinnis smiled back at The Doctor. I can’t wait to see what Doc does to Sidney, McGinnis thought.

****

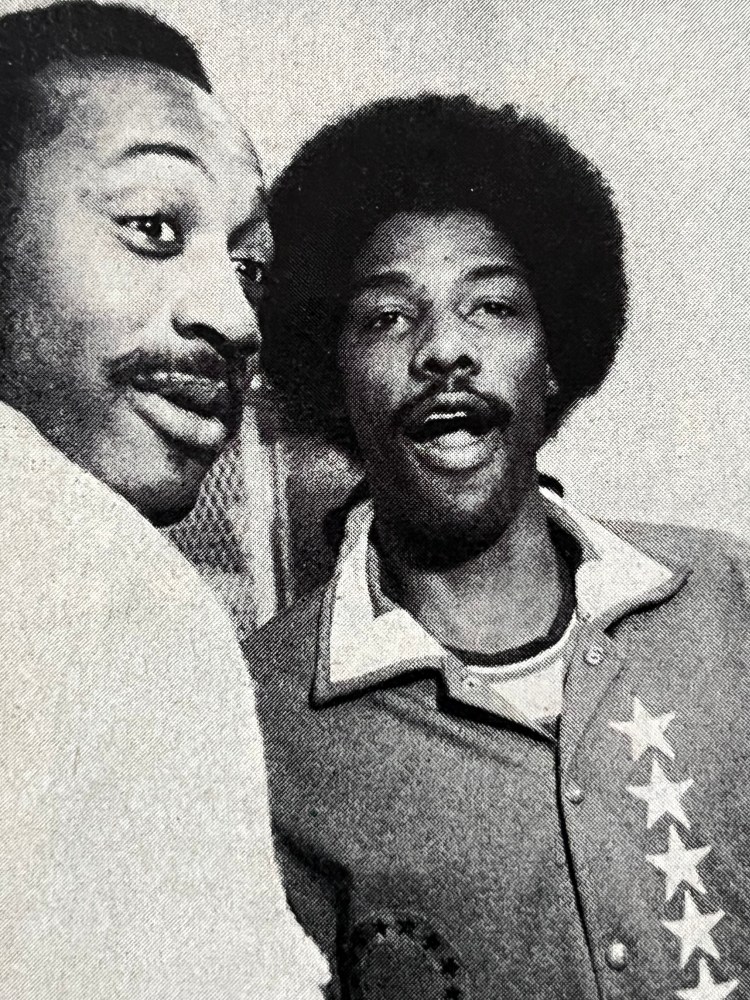

When Pat Williams, the general manager of the 76ers, and Gene Shue, the coach, first considered buying Julius Erving from the New York Nets, they went to George McGinnis and asked him what he thought of the idea. McGinnis was the dominant 76er; he was first team All-NBA in 1975-76, and the year before, playing for Indiana in the American Basketball Association, he had been the ABA’s co-Most Valuable Player, sharing that award with Doctor J. If McGinnis had objected to the deal, Williams and Shue would have gone no further.

“You crazy,” said McGinnis. “If you can get The Doctor, get him.”

McGinnis was among Julius Erving’s greatest fans, and when the sale was announced, when the 76ers heard that The Doctor was about to join them, several players crowded around McGinnis and peppered him with questions: Can the man really do all those things we’ve heard? Is he really that good? And George McGinnis, who has moves of his own that no other player in the world can match, nodded and smiled and said, “You wait. You’ll see.”

****

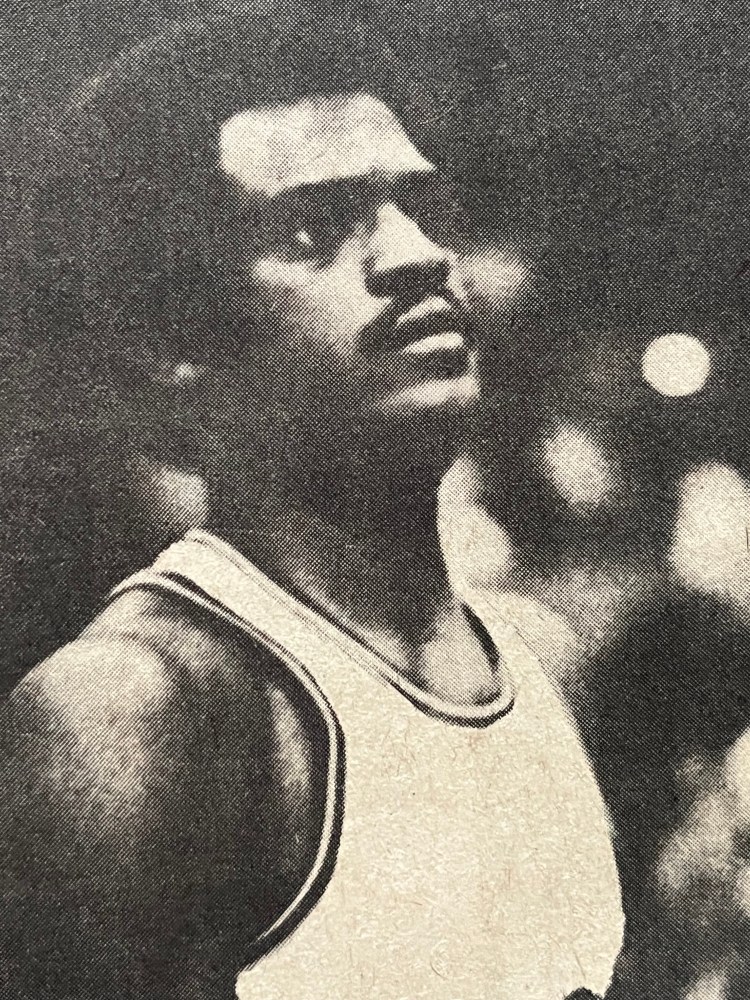

In the first four-and-a-half minutes that night against the Boston Celtics, Julius Erving walked, threw a bad pass, couldn’t reach a high pass from Henry Bibby, and did not score a point. Then it happened.

The Doctor got the ball just outside the foul circle, slightly to the right of the basket, and quickly considered his three options; pass, shoot, or dribble. He saw no teammate open for a good shot. He couldn’t shoot, Sidney Wicks was guarding him too tightly. So he put the ball on the floor. He didn’t exactly dribble. He exploded. With one giant, blurry step, Dr. J bolted past Sidney Wicks. Wicks tried to stay with Erving, tried to stop him. He wanted The Doc, but The Doc had him.

Erving bounced the ball once and went up in the air, left the ground somewhere beyond the foul line, soared, floated, drifted, and then his long right arm reached high into the air, his right hand palming the ball, and his arm came whizzing down, and the ball slammed through the hoop with a sizzling sound, and the rim shivered, and the crowd shivered, and Sidney Wicks, even if he didn’t show it, also must have shivered.

It was only one play, one fast moment of magic in The Doctor’s lifetime of wizardry, but that one play, that super dunk, that shattering demonstration of superiority, seemed to capture the essence of Doctor J. Everyone in The Spectrum had to react.

At the press table, Harvey Pollack, the public relations man for the 76ers, carefully noted that Julius Erving had just achieved his 25th dunk of the young season. Harvey Pollack has been a publicity man in the NBA for almost a quarter of a century, and he was a confessed statistical freak, but he had never before in his life kept track of dunks. “I’ve never worked so hard,” says Pollack. “I get 21 out-of-town papers delivered to my house every day. My wife cuts out the sports sections so I can read about Julius.

“I never got out-of-town papers before. And I have to use place cards in the upstairs press box. Not just down on the floor. Upstairs. I have to get out tags for the locker room. The world wants to talk to him. Playboy,Money, People, SPORT, Women’s Wear Daily. Everybody wants him. Five hospitals in Philadelphia already want The Doctor to visit them. He’s getting $2,500 to spend one hour at the Cherry Hill Mall. We’ve had a press conference for him in every city we played in, except Kansas City in Buffalo. They didn’t ask. I don’t know why. We had nothing like this when we got McGinnis.”

In the upstairs press box, sitting behind someone else’s place card, Pat Williams, the general manager, the man who had to persuade millionaire owner Fred Dixon to part with three of his millions to purchase Erving, shook his head in awe.

“You know what the pressure is on him?” says Williams. “I swear that the crowd has this feeling that every time he touches the ball, something never before seen has to happen. Can you imagine what kind of pressure that is?”

In the stands, all 17,196 spectators were buzzing, congratulating themselves on their good taste in coming to see The Doctor. The crowd was the third sellout in seven games at The Spectrum; the 76ers were drawing an average of 16,000 fans to each home game—an increase of more than 3,600 over the previous season. At an average of $5 a ticket, The Doctor was attracting $18,000 worth of new business for each home game, which would come to more than $700,000 worth of new business for the season’s 41 home games, which would be approximately $200,000 more than The Doctor’s yearly salary. Suddenly, Erving’s ludicrously extravagant six-year contract seemed not only sane but sensible.

On the court, George McGinnis beamed, savoring what he had seen, and stole a glance at Sidney Wicks’ dark frown darker than ever, his confidence obviously shaken. Nine seconds after The Doctor’s dunk, Wicks threw a bad pass, and Henry Bibby intercepted.

****

When Julius Erving became a 76er, Henry Bibby was, at best, the fourth guard on the team—behind Doug Collins, Fred Carter, Lloyd Free, and perhaps even rookie Mike Dunleavy, a sixth-round draft choice from South Carolina. But by the time Erving slid into Philadelphia’s starting lineup, Bibby was there, too. The 76ers needed Bibby in the lineup for one reason: They needed someone who could touch the ball without feeling compelled to shoot it. That is overstatement, of course, but in Erving, McGinnis, Collins, and Carter, the 76ers had four proven 20 point-a- game scorers, without an ounce of bashfulness among them, and someone was going to have to give the ball to them. Bibby, discarded by the Knicks and New Orleans, got the job.

****

Up until the moment Doctor J stuffed the ball over Sidney Wicks, Philadelphia held only a two- point lead over Boston. Within five minutes, the 76ers had built their lead to 14 points, and the team’s superstars, perhaps leaning over backwards to prove they could be unselfish, had shown that they could all pass as well as score. One 76er layup came on a perfect feed, McGinnis to Erving; 40 seconds later, McGinnis took a precision pass from Erving and dropped in a layup; a minute-and-a-half later, Collins threw a lead pass toward the basket, and Erving turned his 6-foot-6 frame into a 12-foot ladder, took the pass up above the rim and, with two hands, stuffed the ball into the basket. Harvey Pollack noted The Doctor’s 26th dunk.

Less than a minute later, Gene Shue elected to make his first substitution of the game: He sent in Steve Mix to replace The Doctor.

****

The day before they opened their 1976-77 season, the 76ers were practicing at Camden Catholic High School. When the word reached the gym that Julius Erving had agreed to terms, Steve Mix felt as if he had been kicked in the gut. “I was playing the best ball of my life,” says Mix, who struggled through rejection by half a dozen pro teams before he became a starter and (one year) an all-star with Philadelphia. “And I knew it was my spot that Julius would have.” At first, Mix continued to start each game, and Erving came off the bench. Then the roles were reversed.

“I felt much more comfortable coming off the bench,” says Mix. “I told my wife that. I couldn’t stand starting in front of Julius. I got very uptight. I knew that people had come out to see him, and I felt they were just waiting for me to do something wrong so that he would come in. As a starter, I was making only 70 percent of my free throws. As soon as I began coming off the bench, my percentage went up to 80.”

****

In the second quarter, Erving came back into the game, replacing McGinnis, and a few minutes later, McGinnis returned, replacing Mix, and not long after that, Mix filled in for the 76ers’ starting center, Caldwell Jones. For the last seven minutes of the half, the three forwards were all on the court for Philadelphia. “I used to play 45, 46 minutes every game,” says McGinnis, and now I play 30 or 35. You know what that’s going to mean for my career? And you know what it means right now? It means that after a game, I can go home and watch TV. I don’t have to collapse anymore.”

In the second half, after a Boston rally briefly tied the score, the 76ers pulled away, strengthening their hold on first place in the NBA‘s Atlantic Division. Erving sat out the fourth quarter. Shue poured his reserves into the game.

****

When Pat Williams told Gene Shue that the 76ers might be able to acquire Julius Erving, the coach was not exactly thrilled by the notion. “I had negative feelings,” Shue concedes. “We were having a great exhibition season. I felt our team was strong enough, without Julius, to win a championship, and I didn’t want to destroy what we had built. I wasn’t sure the addition of The Doctor would substantially improve the team. If I hadn’t been afraid that he might end up with the Knicks or another team in our division, I probably wouldn’t have encouraged Pat to go after him.”

When Shue became coach of the 76ers three years ago, he inherited a team that had won only nine games the previous season, a team that had the least talent in the NBA. Now Shue has the team with the most talent.

****

When the game ended, with Philadelphia in front of Boston by 14 points, six 76ers had scored 13 or more points, and The Doctor was high man with a modest 19. More significantly, he had broken the spirit of Sidney Wicks, who wound up with only nine points and four rebounds, far below his norm. Every 76er had played except one man, Fred Carter, the team’s high scorer in 1973-74 and 1974-75. Julius had made Carter expendable, and in a few weeks, he was traded to Milwaukee for a draft choice.

In his first five weeks with the team, Erving’s impact had been enormous. He had, in a sense, redefined the role of every man connected with the 76ers, from Harvey Pollack to Henry Bibby. He was also able to define his own role. “I can score 30 points any night,” says The Doctor, “but that’s not what this team needs from me. I’m not supposed to score 30. We’d be in trouble if I did. I want to draw two men, I want to make passes, I want to take advantage of my strengths and George’s. And I want to make one good play every game. One good play that I can remember.”

The next day, the 76ers were off to Detroit to face the Pistons, and Julius was off to face another news conference, another barrage of questions about his ability to coexist peacefully with George McGinnis (“We’re both basically unselfish.”) and about his inability to honor his contract with the New York Nets. “I had certain financial expectations that weren’t realized,” says Erving, who does not handle money questions as smoothly as he handles a basketball. “I think Roy Boe [the Nets’ owner] told too many people he wasn’t going to give in to me. He put himself in a bind. He had to sell me.”

At the Philadelphia airport, another passenger, a sturdy man close to 70, recognized The Doctor. “How tall is he, anyway?” the man asked. Neither Julius nor the stewardesses recognized the man who asked the question. He was Harold Stassen, who had almost been nominated for the presidency of the United States in 1948.

A few days later, another man whose name has been linked with presidential aspirations offered his comments on The Doctor. “He’s the best forward in the game,” said Bill Bradley of the Knicks. “He does everything so well. He’s not only unstoppable. He’s embarrassing.”