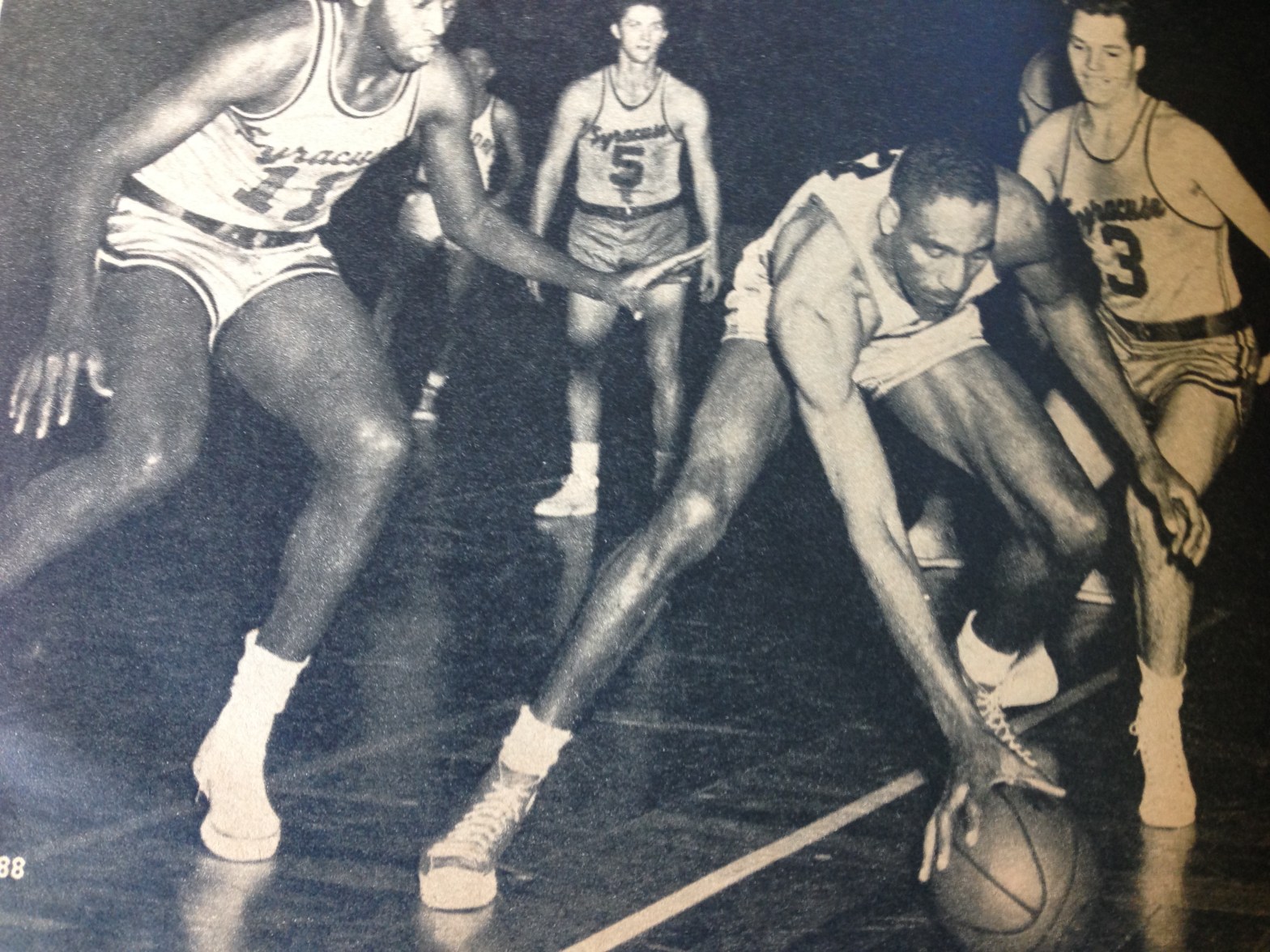

[Above is a 1955 photo of New York’s Sweetwater Clifton collecting a loose ball with Syracuse’s Earl Lloyd (11) and George King (3) ready to pounce. Below is more cut material from one of my books. It offers a helpful intro into the organization of the NBA Players’ Union. Up next: Bob Cousy’s Players Bill of Rights.]

Bob Cousy racked up thousands of assists during his Hall-of-Fame career with the Boston Celtics. He called it “spreading the sugar,” and the internet is filled with grainy, black-and-white film clips of Boston’s original basketball leprechaun dishing out nifty, no-look passes behind his back and, more often, sprinkled magically delicious over his shoulder.

Mostly missing from the internet are grainy mentions of Cousy’s ultimate career assist: setting up the NBA Players Association. Cousy’s interest in a union took shape in the winter of 1954, the NBA’s fourth season in name when he started passing on to his Celtics teammates and a few journalists his profound frustrations with the league. By summer, Cousy put pen to frustration and sent a form letter to a select member of each of the league’s other eight teams. The recipients, like Cousy, were the so-called “untouchables,” whose popularity on their teams and in their communities would seemingly protect them from any retribution if word of the letter and the union organizing leaked to management.

Cousy explained in his letter that the union wouldn’t push immediately for higher salaries or a pension. The NBA was too fragile financially for that. What needed to be addressed first and foremost were basic housekeeping issues. In some venues, rims were crooked. Staff sometimes set up baskets higher than the regulation ten feet. Several courts had phantom dead spots that swallowed up dribbles during games. Don’t even mention the staggering travel schedule and overload of games. In New York, gamblers routinely sat courtside booing and cheering to cover the point spread. When the point spread tightened, especially in the last two minutes of a game, the gamblers congregated behind the basket with their shirts off, waving them like pinwheels to make a player miss a decisive free throw.

“We need class,” he told a sportswriter. “We’ve got to stabilize so we can demand respect.”

“Is that your job?”

“It’s everybody’s job,” Cousy answered. “We can’t go around apologizing because we’re professional basketball players. We’ve got to have pride—pride in ourselves and our teams and in our league. What’s good for the NBA is good for us all—and what’s bad is bad for us all.”

That was easy for a big star like Cousy to say. For the run-of-the-mill guys—and there were plenty of them—they went along to get along. Complain too loudly about playing time or bonuses, and all were replaceable with a snap of the fingers. The league’s standard player contract left everyone, even Cousy, subject to immediate dismissal and their salaries weren’t guaranteed upon termination.

For most, that snap of the fingers would be painful. They’d been stars in college and hoped to play ball for a few more years. Plus, the pro money was decent right out of college in an era when the average home cost just over $8,000. Starting at the league minimum of $3,000 per season, they could double their salaries in a few seasons and live comfortably. Though they’d never bring home the elite $20,000 salary of Cousy, America’s newly crowned “Mr. Basketball,” some could get further ahead in the offseason with a second job. Why bite the NBA hands that fed them. They were lucky to be numbered among the league’s roughly eighty-five players

That number included six established African Americans. They were mostly expected to set screens, rebound the misses, and suffice with playing second fiddle to the white leading men on their teams. Rochester’s Maurice Stokes would soon invalidate this “get-in-there-and-do-the-dirty-work” job description with his high-scoring rookie season. He and Woody Sauldsberry, Bill Russell, Sam Jones, Wilt Chamberlain, Elgin Baylor, and others proving to NBA front offices that they could feature a crowd-pleasing black player and still pack their arenas without inciting white hooliganism. But, for now, any black player who advocated unionization did so at extreme professional risk.

And yet, virtually every player, black or white, could agree with Cousy that that life in the NBA could get downright weird. In Anderson, Indiana a few years ago, the locker rooms had cockroaches that were “literally the size of humming birds” and flew in swarms from wall to wall. In Waterloo, Iowa, when the road team shot free throws, fans cranked up the hot-air blowers that heated the gym, whiffling each attempt like knuckleballs. In Fort Wayne, where the gym was known as “the Bucket of Blood,” fans liked to whack visiting players with hand bags, umbrellas, newspapers, game programs. In Syracuse, there was “The Strangler,” a short, barrel-chested heckler who liked to go nose to nose with an opposing player and yell, “You son of a bitch, you stink!” Then there was elderly woman in Syracuse who enjoyed jabbing Boston coach Red Auerbach with a stick pin whenever he entered the arena. Auerbach even went roaring into the stands after her once.

By August 1954, the survey results were in from seven of the eight teams. (The members of the Fort Wayne Pistons, who answered to their staunchly anti-union owner, Fred Zollner, didn’t want to risk his wrath.) Cousy poured over the responses with Joe Sharry, his partner in a Worcester, MA insurance business and a natural-born salesman, community organizer, and trusted collaborator in forming the union.

The two flipped through the letters at their insurance office in Worcester’s stately Bancroft Hotel and tallied the final landslide vote: Seven in favor, none against. Now came the hard part: convince the struggling, profit-obsessed NBA owners (Fort Wayne’s Zollner excluded) to recognize the union, in proper legalize, as the players’ sole bargaining unit.

Shortly thereafter, Cousy requested a meeting to broach the subject with the man whose difficult last name the players derisively garbled “Poodles” and “Pumpernickel.” He was the 5-foot-2, wide-bodied NBA president (today, commissioner) Maurice Podoloff, now in his mid-60s. His job description was to protect the owners’ financial interests and keep the league running on time.

Poodles ignored Cousy’s query.