[Walt Frazier needs no introduction. The forever-hip, former New York Knicks All-Pro has been the subject of documentaries, books, magazine articles, and newspaper features since the mid-1960s. Some of these efforts are obviously better than others, and this article, from the March 1971 issue of Sport Magazine, is one of the best to capture the “Clyde” mystique during Frazier’s playing days. The article comes from Edwin Kiester, Jr., who went on become a noted historian and science writer. This is another example of long journalism at its best.]

When their normal practice arena in Madison Square Garden is tied up by a hockey game, a rodeo, or an exhibition of campers and trailers, the world champion New York Knickerbockers work out at the Lexington School for the Deaf, a fast bounce-pass away from the LaGuardia Airport runways. The school is a city institution for high-school and junior-high age students and is housed in a new cinnamon-colored brick structure with the latest in gym facilities.

Practice there is scheduled from 11 to 1, but usually the Knicks quit early, during the student hour. So the deaf youngsters gather in the lobby and excitedly gesture to each other in sign language as their favorites pass through and head for the parking area.

One recent day coach Red Holzman was, as usual, the first to emerge from the dressing room. Glowering behind his stubble and wrapped in an old grey topcoat, he was almost across the lobby before the students spotted him. They gave him a riffle of light applause. Dave DeBusschere and Bill Bradley followed, Bill unmistakable in an old Navy peacoat and baggy corduroy slacks. More applause, louder and more prolonged. Next came reserve center Phil Jackson, also in a peacoat. Then the 7-feet-1 rookie, Greg Fillmore. Then Willis Reed, Mike Riordan, Dave Stallworth, Dick Barnett. As each appeared, the applause rose or fell according to his reputation and his response to the greeting.

Finally, Walt Frazier came gliding down the corridor, moving in his distinctive loose-limbed stride. The Knicks’ star guard, basketball’s most elegantly dressed player, was rigged out in a camel hair topcoat with matching flat cap. His suit was a blue-grey whipcord, with riverboat gambler lapeled vest, and beneath it a pale blue shirt, with a fashionably wide white tie showing in the V of the lapels. He wore two-tone box-toed shoes, charcoal-grey and mauve. When he waved to the students, a bracelet studded with diamonds spelling “Clyde,” his nickname, flashed from his right wrist. Even white teeth gleamed against the black mustache and muttonchop side whiskers that framed his smile, the most magnificent bush of facial hair since President Chester A. Arthur.

This splendiferous vision set off instant bedlam. Kids jumped onto the Naugahyde sofa and the reception room tables, waving at Frazier, wigwagging him the V-for-victory sign. The lobby filled with excited, piping vocal sounds, Frazier, smiling and waving in return, clapped one or two students on the shoulder. He stepped out of the lobby and into his lemon Cadillac with the white leather upholstery. The students followed, crowding to the windows, still waving, V-signing, beating on the glass. Not until the car swung down 75th Avenue toward the Grand Central Parkway did they turn back to class.

Something about the 26-year-old Frazier electrifies people that way, whether they are teenagers who cannot speak nor hear, or basketball fans with full capacity to scream and holler their heads off. When he is on the basketball court, a crowd sits up in anticipation, looking for the flashy ballstealing that has made him the most spectacular defensive man in the league. “There is only one way to beat the Knicks,” says coach Jack Mullaney of the Los Angeles Lakers. “Keep the ball away from Frazier.” Says an admiring Bill Bradley: “I have yet to see anyone intimidate the opposition the way he does.”

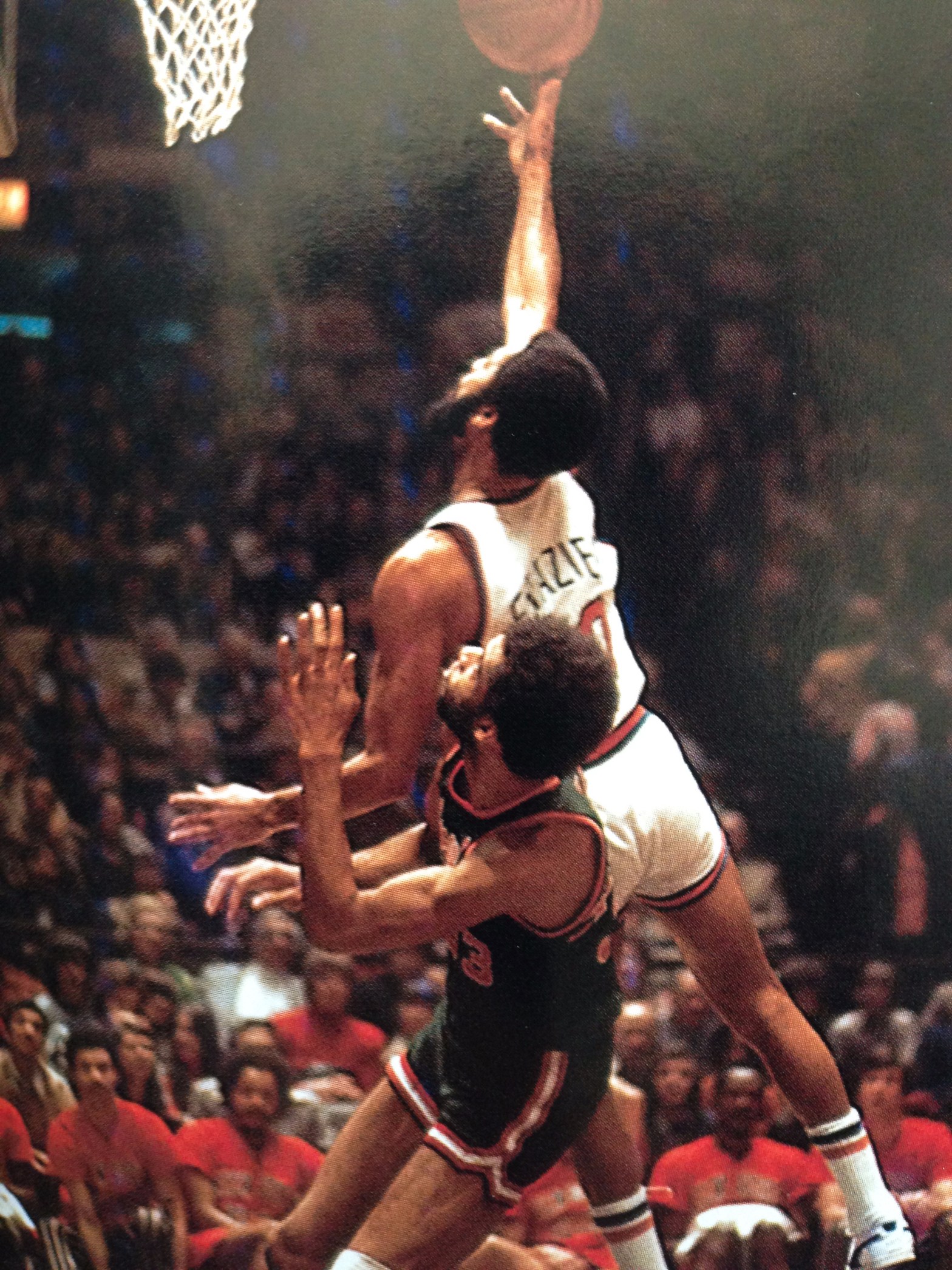

Twice an All-NBA selection, twice voted to the All-Defensive team, twice an All-Star, Frazier is obviously a superior basketball player. But it is not only his technical skills that shoot off the Clyde brand of sparks. Last season it seemed that every time an opposing player got just a little bit too careless, a café-au-lait arm stabbed out and whisked the ball away. And, Bradley says, “It’s not only that Clyde steals the ball, but that he makes them think he’s about to steal it, and that he can steal it any time he wants to.”

The San Francisco Warriors know all about that. In the clubs’ first meeting this fall, in San Francisco, the Warriors thought they had the champions beaten. In the third quarter, with the Warriors well ahead, guard Ron Williams casually brought the ball upcourt. He was working against Frazier, one on one. Suddenly, as Williams reached midcourt, Frazier shot forward, flicked the ball, raced around Williams to recover it, dashed for the basket and scored. Ten seconds later, the scene was repeated. Before the half ended, Frazier had stolen the ball from the Warriors nine times, converted six of the steals into baskets, thoroughly demoralized the Warriors, and led the Knicks to a 111-99 victory. When he left the game seconds before the end, the pro-Warrior crowd gave him a two-minute standing ovation.

At all times on the court, Frazier is unruffled, unflustered, unflappable. He seldom works up a sweat (a physical quirk, he says), never fights and never verbally disputes an official’s call. (Sometimes, he confesses, he returns the ball extra hard to indicate his displeasure.) Offcourt, he is similarly low-key. He is able to describe himself as “neutral” on even so controversial a subject to most black athletes as civil rights. He sometimes sleeps 18 hours straight, leading roommate Mike Riordan, the reserve guard, to say that Frazier is ideal to bunk with—”You never know he is there.”

Some people say Frazier’s total affability is a smiling façade, but if so, beneath that smiling façade is another smiling façade. Acclaim has gone to smaller heads then Frazier’s, but if the broad-brimmed, wet-look hats he favors have had to be enlarged, it is not immediately evident. One sportswriter recalls that Frazier is the only athlete who ever volunteered to come to the writer’s home for an interview, just to be helpful. When I interviewed Frazier, I jokingly called his attention to my own new off-the-rack grey flannel slacks. Without a trace of disdain, the man who pays $300 for tailor-made suits inspected the slacks, pronounced them a fine set of threads, and threw in for good measure that my tie was nice, too.

Clothes are one way the Frazier flamboyant streak shows up off the court. He owns more suits than he can keep track of—”around 50, I guess”—including such spectaculars as a lemon-yellow linen and a sky-blue worsted. His latest acquisition is a $950 elephant-hide topcoat, which hangs in his closet next to one of sealskin. Suits are tailored to his design, The “Clyde Special” has lapels wide at the pectoral line, darting sharply towards the waist. He is now in the process of phasing out his lizard and alligator shoes, which he bought at $200 a pair, to replace them with more modish box-toed models.

Frazier recently moved into a three-room, tenth-floor penthouse on Manhattan’s East Side. It might be described as part way down the road to Joe Namath-land. The place is only partly decorated, because Frazier, no dummy, keeps recruiting girl volunteers to come up and help with the selection of drapes and linens. (Married in college, Frazier is now divorced and has a young son, Walt III, living in Chicago.) The decor so far gives a sample of his—and their—taste. The living room is carpeted in plush broadloom, about the color of a hook-and-ladder truck. It features two curved, armless sofas in Chinese red and jet black, each of them long enough for a 6-feet-4, 205-pound backcourt star to stretch out, and two matching beanbag chairs. The bedroom carpet is wall-to-wall cream-colored shag. One bedroom wall is taken up by closets, to contain all those clothes. Another is planned as a floor-to-ceiling, wall-to-wall mirror, with Clyde etched in foot-high letters near the top. The other two walls are to be upholstered in purple velvet. Most of the floor space is occupied by a mammoth round bed.

With salary and outside earnings reaching six figures, Frazier can afford this luxurious lifestyle. He and the other Knicks cashed in quickly on the hero worship with which that town of hayseeds, New York, welcomed its playoff victory last May. Frazier is now the author of an autobiography, Clyde, written with Joe Jares; co-owner, with Mike Battle of the New York Jets, of a mod hairstyling salon (never to be called a barber shop), Battle and Clyde’s; president of All-Star Sports, which he founded with eight other New York football, baseball, basketball, and hockey players to arrange promotions, endorsements, and personal appearances. He also opened a basketball camp for boys at Pawling, New York, and began a basketball season sports broadcast on Harlem radio station WLIB. And then there is the stock portfolio.

Yet sitting in the penthouse recently, crossing one custom-shod foot over the other and listing his business interests, Frazier felt he hadn’t really changed much since his days at Atlanta’s Howard High. “Howzat again, Clyde?” came the question. But as Frazier explains it, he may be right.

Frazier came to the Knicks out of Atlanta by way of Southern Illinois University, which is covering more ground than a mileage chart would indicate. The black district of the South’s largest city is not as squalid as the tenementized warrens of the urban North; it is characterized more by small single-family houses, duplexes and tree-shaded sidewalks. But if not “pinchin’ poor,” in Lincoln’s words, it is hardly affluent, either. Frazier shared his duplex apartment with eight younger children and his grandmother. He learned to play basketball on a rutted dirt playground at a segregated high school.

From the time Frazier was nine years old, matching up against 12-year-olds a foot taller, he kept reaching certain conclusions about the game of basketball. The first was that aphorism, “The best defense is a good offense,” had things backwards. In basketball, aggressive defense comes first. Harry your opponent, press, steal the ball, keep him flustered, never allow him a clear shot. If he doesn’t get a chance to hit the basket, he can’t win; you only have to score slightly more than he. Part Two of the Frazier gospel was that taking a wild shot yourself was lots of fun, but hitting an open man under the basket was more fun. “When I go back to Atlanta, my old coach, George Coffey, says, ‘You play just like you did at Howard High,’” Frazier declares. Before he was 10 years old, Frazier’s game was set and he has not deviated from it since. All that has happened is that professional basketball has caught up with the Atlanta playgrounds.

In 1969-70, no member of the champion Knicks was among the league’s top scorers. The highest was Willis Reed, who stood 15th. As a team, the Knicks were ninth in scoring, next to last in rebounds. Yet in one department the Knicks stood first by a wide margin. They yielded just 105.9 points per game, six points fewer than their nearest rival, the Lakers. They won not when they had the ball, but when they didn’t.

While the others lay back, playing one on one, Frazier was out front, trying to intimidate the opposition into playing the game the Knicks’ way. Mike Riordan uses a football analogy to explain how the all-for-one-and-one-for-all system works: “The four of us are like the defensive secondary. We each have our responsibilities, our men to cover, and we play conventional one-on-one defense. When the threat goes one way, we help each other out, like double coverage on a pass receiver. Clyde is the free safety. The other team never knows what he is going to do. He roams, turns up in different spots. If he guesses wrong, gets out of position, we cover for him. If he gets the ball, we’re ready to help him. Most of all, he makes them change their style of play to accommodate him.” Frazier himself says, “Defense is not something passive. Defense is a weapon. You’ve got to take gambles in order to put pressure on the other team.”

Defensive basketball sounds dull. And the results are negative, but not by the bing-bing-bing of points mounting on the scoreboard but by silence on the opponents’ side. Yet the Knicks have managed to make defense exciting, and to convince their rooters of its thrills. Madison Square Garden is probably the only basketball arena in the country where, when the home team falls behind in the fourth quarter, a chant begins in the lower tiers and swells until it sweeps the arena: “Dee-fense! (clap, clap), Dee-fense! (clap, clap) Dee-fense! (clap, clap).”

The chanting was heard loud and clear one afternoon during the past Christmas holidays. The Knicks were trailing Baltimore, 81-74, going into the final period. Then, subtly, the nature of the game began to change. Bullets began to miss passes, to throw the ball away. Their patterns tangled up in Knick feet.

Four minutes passed, the Bullets scoring only one goal. Meanwhile, Frazier contributed three goals, Bradley two, Barnett two. With two and a half minutes left, the Knicks tied the score. Frazier doing it with a long, flashy, leaping shot from the right of the key. DeBusschere sank two free throws to put the Knicks ahead. Loughery scored from outside to tie again. Frazier shot from the corner to restore the Knick edge.

Then came the play that broke the game open. Monroe, driving for the basket, met Dave Stallworth, who managed to get a hand into the parabola of the shot. The ball was deflected to Frazier, who flipped to Barnett breaking down court, who returned to Frazier for an easy layup. Fouled on the play, Frazier converted one of the free throws to make it 105-100, with 1:07 to go. Ten seconds later, he intercepted a Bullet pass and whipped it to Reed for a quick jumper. The final score: 110-105, Knicks.

Not even some experts appreciated just how the day was won. “We got everything this afternoon but the win,” complained Baltimore coach Gene Shue. The Bullets had 68 rebounds to the Knicks’ 46 and took 115 shots from the floor against only 86 for New York. The Bullets complained that their shooting eyes were off—their percentage was only .375, and Johnson was 4-24 from the field. No one pointed out, however, that their eyes may have been off because they were allowed no opportunity to focus them.

Once again, the Knicks had played, and won, on their own terms. Frazier scored 33 points, high for the game, but professed himself more elated by the blocked shot, his seven assists, eight rebounds, and three steals. “I get my thrills by stealing and making good passes,” he says.

It is a fact that the Knicks play their better games against their stiffer opponents, their lesser exhibitions against the more mediocre teams, and Frazier is no exception. He is a man who rises to occasions—witness his play in the deciding game of the playoffs last year. When the Knicks, with minimum help from the injured Reed, beat the Lakers 113-99, and Clyde scored 36 points, with 19 assists and five steals. “Something about competition gets me psyched up,” he says. “It’s psyches us all up. It has something to do with the fans. The more they yell and cheer, the harder we play, and the harder we play, the more they yell and cheer.

“It’s like steals. When I make one, it really excites me. I start to think I can get them all. I’ll make two, three in a flurry. Sometimes I’m not even careful, it seems like. I’m all over the floor, taking gambles. Ball’s on the other side, the center is bringing it up the other side from me. I’ll still go for it. I get so psyched up I can’t stay away from it.

“In that game against San Francisco, some of my steals were spectacular. I don’t know even how I made them myself. Seems like I’d just come out of nowhere. I got two or three in a row, and then every time you looked up, I had the ball on a fast break. Most of the time it wasn’t even my man I stole the ball from. I just left my man to come and help out and make the steal.

“I guess that was my favorite game this year.”

One of the more interesting developments of the 1970-71 Knicks has been the blossoming of Frazier into a major offensive threat. Of course, he has always had a keen basket eye, particularly from about the 15-foot range from the left side, and last year he did average over 20 points for the first time. But in the first half of this season, he had games of 34, 33, and 31 points, and Holzman was professing publicly to be pleased with the development of his No. 1 defensive player into an offensive hero. “He has more confidence in his shooting now,” Holzman says. “He has become a good outside threat and that helps our shooting inside. He takes his shot now when he should take it and passes off when he should.”

Frazier himself also interprets his emergence as an offensive threat as a mere matter of maturity. “I was different from most rookies when they first come up,” he recalls. “They usually have the offense and have to learn to play defense. I was just the opposite, I played good defense but I wasn’t sure of myself on offense.

“It wasn’t that I couldn’t make the shots. I could make the shots or I could pass off, but my problem was knowing which to do. I passed when I should have shot and shot when I should have passed. I looked bad. It was embarrassing.

“My rookie year, I really played lousy. Of course, what complicated everything was that I was hurt in the exhibition season. I missed 10 games and 10 regular-season games and when I came back I was lacking in confidence. I just didn’t feel part of the team. I didn’t look for my shot. If I missed the first shot, I didn’t shoot again for the rest of the game. As far as scoring went, I didn’t. I was blowing even the easiest layups. Then halfway through the season, it was like everything happened overnight. I was driving and penetrating and hitting the open man. It was like destiny or something. I was the player I knew I could be.”

One thing Frazier omits from his chronology of development is that in mid 1967-68, the Knicks fired coach Dick McGuire and replaced him with Holzman, until then the chief scout.

“Red came in with the idea of playing defense,” Frazier says, “and that was right down my line. With him I really began to get playing time. Coach McGuire didn’t have confidence in me, but I didn’t blame him. I wasn’t delivering for him. He was under a lot of pressure to win. The club had just signed Bradley and people were expecting great things. When we kept losing, something had to be done.”

Frazier’s basic offensive role is playmaking and feeding the ball to his teammates to score. He has been compared to the quarterback on a football team, both in the sense that he makes the play selection and that he hands off the ball to start the play going. The comparison has been somewhat overdrawn. Frazier is the Knick who brings the ball upcourt (“On the Knicks,” Reed has said, “the ball belongs to Frazier. He just lets the rest of us play with it once in a while.”) And often you will see him signal with upraised fingers, or shout out “Bailey Howell” or “Trap” or “Thirty-three” or one of the code names the club uses to signal a pre-arranged pattern of screening and passing and faking that will eventually shake one man open to score a goal.

But Frazier only calls about half the plays—”The rest of the time it could be Dave or Barnett or Bradley or Red from the bench”—and in any case the Knick offense cannot be characterized as simply a matter of X’s and O’s interlacing in a kind of graceful and ritualistic 18th century gavotte. Often the Knicks do not use any plays—the 24-second rule limits how intricate a pattern you can run, anyway—but simply play fundamental basketball. Dave DeBusschere likens the tactics to those of the Green Bay Packers in the heyday of Vince Lombardi. The Pack simply ran their power sweep and defied anyone to stop it. “We don’t care if they know what we’re going to do or not,” DeBusschere says. “In fact, we like it better when they know. Then we can predict how they’re going to play us, and we can respond to that.”

However, there is a kind of Circadian rhythm to every game, an ebb and flow which Frazier directs. Holzman Insists that he bring the ball upcourt on every Knick out, and it’s his judgment of what he sees as he comes that guides the attack. Frazier is blessed with almost perfect lateral vision, and he can take in the whole floor ahead of him as he dribbles, shifting the ball smoothly from hand to hand as he studies the players’ deployment.

“When you come up,” Frazier explains, “there are basically three things you can do. You can pass off to the left, you can pass off to the right, or you can take it in yourself. Before you decide, you must consider a couple of things. One, who has the hot hand, or who has the weak defender against him? If Reed has made three jumpers in a row, or Barnett has the range from his corner, you want to work the ball so that he ends up and takes the shot. Two, you want to mix things up so that everybody gets involved, everybody gets his shot. If one shot goes to Reed, maybe the next should go to Bradley. Or you make it look like it will go to Bradley and give it to Reed, if he’s hot. Everything we do, we have a couple of possible options so that different guys get the shot. Or maybe you let the guy fake the shot one time and the next time he comes back and goes for it.

“Plays themselves are really only good for certain situations. Like when Cazzie is playing (Russell was injured at the time) and we have a last-second shot, we want him to be the one to take it. We work the ball so that he gets it. Now, without him, we use Bradley for the last-second play.

“Other times plays are good are when you’re behind. You run a play and that slows the game down, and it helps you settle; you run a pattern and that gets you moving again. We don’t have plays for the fastbreak and stuff that Baltimore does. We don’t fastbreak that much. More often, it’s a steal and then a pass to Bradley in the corner, or it’s getting the rebound out. It’s a fast thing where everybody moves and knows where the other guy is instead of setting up play patterns.”

These few quotes from Clyde’s Book of Basketball Strategy were delivered one afternoon before the Knicks were to face the Chicago Bulls in the Garden. The Bulls, second to Milwaukee in the league’s Central Division, had won six games in a row before coming to New York. They were employing a flashy offense and a stubborn defense keyed around such strong boys as Tom Boerwinkel and Bob Love. When the game began, however, it was as if Frazier had written the script.

First came the flurry. It was Frazier himself who engineered it, scoring on a driving layup, then a nice short jumper, then on a one-hander from the corner. Then Barnett became hot. Frazier guided the offense so that Barnett got three shots in a row. The score quickly stood at Knicks 12, Bulls 6. The champs then eased up, and at the quarter the Bulls had pulled up to 25-22. In the second quarter, the Bulls took command, leading the Knicks at times by seven points. When that happens, you could see Frazier deliberately slow the pace. At the half, it was 46-46 and the teams played on even terms throughout the third quarter, never more than seven points separating them. Then, in the fourth quarter, the Knicks tooled up their defensive weapon. With a full press, they limited the Bulls to 17 points, while scoring 28 themselves. And it was all Frazier, feeding to the hot hands—first to Barnet for a couple, then to Stallworth, then to DeBusschere at the base of the key. Working methodically, Frazier repeatedly caught the Bulls leaning the wrong way as he set up an open man on the other side. He was like an orchestra leader, cueing first this instrument and then that, following a score that he carried in his head. His expert direction gave the Knicks 22 points in the first nine minutes of the quarter, to the Bulls’ seven. At that point, it was all over. The final score was 98-87.

Chicago is one of the young teams for whom Frazier holds a healthy respect. Being champion has been a new experience for the Knicks, in that everybody is up for them. Even an expansion team like the hapless Cleveland Cavaliers hypes itself up to take on the Knicks. “You can’t take anybody for granted,” Frazier says. “Those Cleveland guys, they played us a hell of a first half. It was tied 50-50 at the half in that first game. We have to watch that kind of thing, letting down against teams like that, letting them get set for us. They can beat us same as anyone else. We got to show right off that we’re champs. If we let them hang in there, play along with them, they can come out on top.”

Of all the NBA teams, however, Frazier fears Baltimore most. “That’s the big threat. All three games we played them this year, they were nip and tuck all the way, they were like the playoffs. Now the (Milwaukee) Bucks, they’re a great team, but they’re not as deep as us, we can go to the bench for eight men. Lew (Alcindor) and Oscar (Robertson) are the nucleus of their team. Take one away, and they’re just average. Take one away from us, like we lost Cazzie, and we adjust.

“Another thing, Baltimore is a similar kind of team to us. They have five strong players. There’s real tough matchups, DeBusschere and Gus Johnson, Willis and Unseld, the Pearl (Monroe) and me. Nobody has an easy mark. All five keep the pressure on. Now with the Bucks, it’s like five on two, the rest of us can help out against Lew and Oscar. With the Bullets, you can’t leave your man to help the other guy or you’re in trouble.”

The Bullets also feature the toughest man Frazier has to guard—”lately, anyway”—in Earl Monroe. “It’s hard to say who’s toughest; it’s like trying to pick the best player in the NBA. West, Oscar (Robertson), (Dave) Bing, he scored 29 points against me the last time, they’re all basically the same. Now that Bing, he does it all, he’s quick, a great leaper, has a fast release, he can shoot outside and drive, too. But Monroe, he’s uncanny. He jumps in the air, turns around, shoots, you swear he isn’t even looking at the basket, couldn’t even be seeing it. But there it goes, swish, right through. He has all these moves to throw you off balance, like he turns around in the air and passes off, just leaves you hanging there. He likes to leave you hanging like that.” Monroe gave Frazier what he concedes was the worst single day in his playing career, in the first game of last year’s playoffs. The Baltimore star scored 39 points, even though Frazier “kept a hand in his face most of the time.” Later in the playoffs, he scored 34. In their most recent meeting, the Pearl had 31. Someone asked Frazier afterwards how he liked guarding Monroe. He laughed. “The thrill is gone,” he said. “He is a horror.”

”There’s only one way to play the Pearl,” he says. “You’ve gotta play him straight on, like I’m standing here facing you. You can’t give him either side or overplay him or he’ll go right away from you, he can handle himself so well. I tried to plant myself to check his momentum because of his knees, you know? I figured that might throw him off. Once he starts to penetrate and gets within shooting range, it can be goodbye.”

With most others, the Frazier technique of guarding is different. “I don’t believe in contact defense,” he says. “I stay back from them, not up close. My philosophy is, I like to keep them guessing where I am. I have the advantage because my hands are so quick. It’s like I’m playing possum, I’m there but I don’t look like I’m there. They’re relaxed more than if you’re up there pressuring them all the time. That’s when they get careless.”

On the court, Frazier is dynamic; off the court, the style is something else. Of his teammates, Frazier is closest to Phil Jackson, Mike Riordan (“what we have in common, see, is we both like to sleep in a freezing room”) and Willis Reed, with whom he keeps up a running banter, mostly about clothes. Reed is resplendent in his own right, but no match for Clyde. Recently he turned up for a game in a beige knit suit, a lavender print shirt, and white cap with a pompon on top. “Clyde,” he said to his teammate, who was in a pink shirt and burnt umber suit, “you’re going conservative.”

But Frazier basically describes himself as a loner, as are all the Knicks, however close a band of brothers they seem on the floor. Generally, they don’t socialize except at games or at practice. Clyde may join them for a few beers at Harry M’s, their favorite bar near the Garden, but afterwards he goes his way and they theirs. “It’s not that we don’t like each other, we just have our own friends,” Frazier says. “I go all over, East Side, Harlem, some of the dancing places around, I never see them.” Among his closer friends are Erich Barnes of the Cleveland Browns and some of his partners in All-Star Sports.

One of Frazier’s favorite pastimes is sleeping, which he indulges in as frequently as possible. If there is no workout, he’ll usually stay in the rack until noon, and on road trips he may sleep later. Sometimes on arising, he’ll workout a little with weights. In the new penthouse, he plans to prepare his own breakfast—”the oldest of nine kids, you learn to cook”—but generally he eats out. Some days after practice he’ll call at the office of All-Star Sports, make a personal appearance or sit for an interview. His relationship with the hair-styling salon is tenuous. He gets his hair done there. Otherwise, he just collects checks for his share of the profits, via his lawyer.

On game days, the first order of business is to ignore the coming contest. Looking ahead to the tipoff, according to Frazier, trying to figure how you might guard Monroe or Greer or Jerry West, is a sure way to get uptight. “Even the night before, I want to go out and relax, do what I want to do. I seem to play better. I know a lot of guys have to talk to themselves, get themselves all psyched up for their opponents, but that doesn’t work with me. Few minutes of that, and I start thinking of something else.”

One new experience for Clyde; newspaper criticism earlier this year, to the effect that he was concentrating too hard on scoring points and making steals, ignoring the bread-and-butter of playmaking and defense. The whispers were that Holzman had to come down hard on him a couple of times about sloppy defense work. Both men denied it, and so did the other Knicks, who, of course, said that he was just as alert, aggressive, and agile on defense as ever. Reed said, “I’d rather play with him than any guard in the league.” Riordan added, “He’s in a niche of his own, certainly the best man for that position for his team.” Said DeBusschere: “People say he has improved on offense, but they don’t notice what’s happened to his defense. Now he knows each player in the league and what to do with him. When he first came up, he played everyone the same way. Now he adjusts. He has great anticipation of what each man will do and where the pass will go. People think he plays recklessly. He doesn’t. I see him go for the ball, I know he’s figured the risks, and I’ll leave my man, go for where the ball will be. That’s how we upset the other guy’s patterns and keep him flustered.” Holzman said: “The great thing about Clyde are his hands, his anticipation. That quickness, he always had that, even in college. Now he knows how to direct it, what to do with it.” And Bradley: “He is the only player I’ve ever seen I would describe as an artist, who takes an artistic approach to the game.”

Many fans were thinking the Knicks might not repeat this year, that their won-lost record compared to last season’s already showed they could be taken, despite their dominance of the Atlantic Division. The repeated mysterious injuries and illnesses of Reed, the loss of Russell for half the season and the uncertainty of his recovery also raised doubts. Plus the fact that everyone was out to get them. “Everybody wants to beat the best,” Frazier says. “When I was a rookie, it was the Celtics.” Some of the conventional wisdom was that Baltimore and Milwaukee are more likely to go all the way.

The playoffs begin late next month, and the Knicks already take for granted they’ll be in the finals as well as semifinals. Frazier, looking back, says last year’s seven games against Baltimore and seven against the Lakers were “just one climax after another—the greatest period of my life.” Besides, there’s that penthouse, that new lifestyle to finance.

One thing is for sure, anyway. With Frazier in the lineup, the 1971 windup will yield nothing to 1970 in excitement. As the kids at Lexington School know, where Frazier goes, excitement follows.