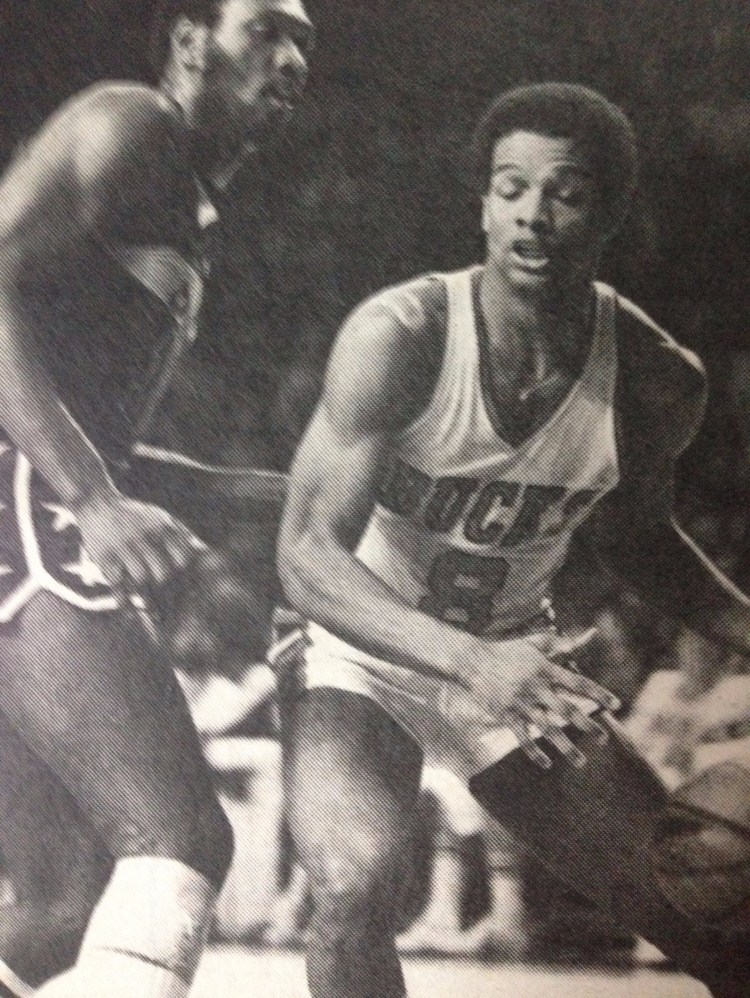

[More Marques Johnson. This article comes from Sports Quarterly’s Basketball Special, 1979-80. The byline belongs to the late-great Frank Litsky,]

Last June at the National Basketball Association’s annual meetings, Sam Goldaper of the New York Timesposed a question to the assembled general managers and coaches.

“Let’s say you’re starting an expansion franchise,” he said. You can pick any five players. Who would they be?” The question isn’t easy, and the answer isn’t easy. Do you pick an all-star team? Do you favor youth over experience? Do you look for team players or individual stars?

The voters seemed to agree that the most important qualities should be youth, defensive ability, and box-office attraction. They also wanted players who would complement one another.

The front-court players who received the most votes were Bill Walton, the new center of the San Diego Clippers; Moses Malone of the Houston Rockets; Marques Johnson of the Milwaukee Bucks; and Walter Davis of the Phoenix Suns. The backcourt favorites were Dennis Johnson of the Seattle SuperSonics; Paul Westphal of the Suns; George Gervin of the San Antonio Spurs; and Phil Ford of the Kansas City Kings.

Johnson was picked as both power forward and small forward, and his 13 votes were the most received by anyone. Walton and Dennis Johnson were next with 12 each, and Ford had 10. In other words, the people who should know pro basketball the best say the most desirable superstar in the game is 23-year-old Marques Johnson.

Who is Marques Johnson, and why is he so good? To start with, he has the physical equipment for the game. He is 6-feet-7 and 218 pounds. His upper body is muscular and strong. He has a 33 ½ -inch waist, but he requires size-35 trousers because his thighs are so large. He has long arms (his shirts have a 38-inch sleeve), and he has the grace, style, and smoothness of a little man. He is quick enough and strong enough to rebound with one hand when necessary.

After a glorious college career at UCLA , he started what so far has been a glorious pro career at Milwaukee. As a rookie in the 1977-78 season, he played in all 80 games, averaging nearly 35 minutes (tops on the Bucks) and 19.5 points a game. He finished sixth in the NBA in offensive rebounding behind Moses Malone, Marvin Webster, Elvin Hayes, Artis Gilmore, and Truck Robinson, all taller or stronger.

In 1978-79, his second season, he averaged 25.6 points a game. That was third best in the NBA behind Gervin and Lloyd Free, both renowned gunners who seldom worried about playing both ends of the court. He finished eighth in field-goal accuracy (55 percent) and averaged 36 minutes a game.

One secret of Johnson’s success is his ability to play two positions—power forward and small forward. Another secret is that he is on the court for three-quarters of the game, more than most players.

“When I came in,” he said, “I didn’t feel I would have to be strictly a small forward, but I’m not physical enough to be strictly a power forward. I thought I could be both, depending on the given situation. That’s been the case so far. I can use my quickness against bigger forwards to my advantage and my strength against smaller forwards. I get baskets when I’m in a position for the offensive rebounds, and I get some in the transitional stage of a play on a fast break.

“I’ve been lucky that I’ve been able to play. You hear a lot about not bringing rookies on too fast, but I wouldn’t trade starting last year for anything. I started from Game One and I got to learn against the best. I look at Greg Ballard, who I played against for four years in college. He’s behind Elvin Hayes and Bob Dandridge at Washington, and he hasn’t had the chance to play and mature as a player as I have. I’d rather play and make mistakes in the beginning. It’ll pay off in the long run.”

Don Nelson, the Milwaukee coach, knew Johnson would be a gem, but not so soon.

“When you see people play in college,” said Nelson, “you anticipate how they’ll be in the pros. We didn’t think at the time Marques would do this right off the bat. We thought he was two or three years away.”

Al Attles, coach of the Golden State Warriors, knew Johnson would be a quick star. “He knew he was good before,” said Attles, “but he didn’t know how good. Now he knows.”

But if Marques Johnson is a superstar already, the Bucks want to know why he doesn’t get the superstar treatment. It is a fact in the NBA that superstars get fewer offensive fouls called on them than do ordinary players. When a superstar drives for the basket and there is contact, the odds are stronger against the defender than normal.

“Marques Johnson is a superstar,” said Nelson. “Why isn’t he treated like one? He should be going to the foul line 10 or 12 times a game like the others. He goes to the basket as well as anyone.”

Johnson agreed, saying:

“There are a lot of times that I feel I don’t get the calls I should. But I don’t say anything to the officials. I never do. I never have. All through college—even before college, all the time I’ve been playing basketball—I’ve never argued with officials. I didn’t think it would do any good. But maybe I should start. “

In truth, Marques Johnson has been a superstar from the day he was born June 17, 1956, in Nachitoches, La. A few months before his birth, his parents watched the Harlem Globetrotters play. His father was entranced by the dribbling magic of Marques Haynes of the Globetrotters and vowed that if the baby were a boy, he would be named Marques.

The father was a basketball coach, and, by the time Marques was four, he had been taught to dribble the length of the court without losing the ball. Marques was five when the family moved to Los Angeles so Marques could be closer to UCLA, the college his father had picked for him.

At 11, Marques was 6-feet tall and playing one-on-one with his father. As a high school senior, Marques played center and averaged 27 points and 18 rebounds a game. He had more than 200 college scholarship offers, but UCLA seemed only mildly interested.

That changed when he played the last two rounds of the Los Angeles high school championship at UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion and scored 26 and 29 points. Soon after, he met John Wooden, UCLA’s legendary coach, at a clinic. “I’ll see you next year,” said Wooden. And he did.

As a UCLA freshman, Johnson started occasionally. As a sophomore, he became a full-time starter and UCLA won the NC AA championship. Wooden retired after that, and Gene Bartow, the new coach, struggled through a player mutiny and a 28-4 season.

Johnson was confused. Like most of his teammates, he had difficulties relating to the new coach. And this was a time when the American Basketball Association was still in business and competing with the NBA for talent.

The Denver Nuggets of the ABA wanted him to leave college and sign with them for $1 million over five years. The Detroit Pistons of the NBA were after him to enter the NBA hardship draft and accept a similar offer. But as Johnson was about to take the Denver offer, the Nuggets withdrew it, apparently fearing that they would upset the impending merger of the two leagues.

Now the Pistons, feeling they had Johnson all to themselves, trimmed their offer to $100,000 a year. Johnson was insulted, but he was ready to accept. At the last moment, he changed his mind and went back to college.

Of course, the story had a happy ending. Marques Johnson, senior forward and captain, averaged 21.4 points and 11.1 rebounds a game. He led UCLA to a 24-5 record and its 11th straight Pacific Eight title.

He finished college as UCLA’s fourth-leading all-time scorer (behind Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Bill Walton, and Gail Goodrich) and fourth-leading rebounder (behind Walton, Abdul-Jabbar, and Willie Naulls). In a decade of such UCLA All-America forwards as Sidney Wicks, Jamaal Wiles, Dave Meyers, and Richard Washington, Coach Marv Harshman of Washington called Johnson “the best they’ve had so far, the best forward I’ve ever seen in college basketball.” One pro scout described Johnson as a “bigger, quicker, younger, stronger version of the great Elgin Baylor.”

Johnson became a prize in the NBA’s 1977 draft of college players, and the Milwaukee Bucks had a pocketful of prizes. They had the first choice in the draft because of their terrible won-lost record the previous season. They traded Swen Nater, their only center, to the Buffalo Braves for Buffalo’s first-round pick, the third overall in the draft. And, in a deal with the Cleveland Cavaliers, they had the 11th choice in the draft.

Milwaukee’s first choice was Kent Benson, the lumbering center from Indiana University. The Kansas City Kings then picked Otis Birdsong, a strong shooting guard. Milwaukee, choosing next, took Johnson, and on the 11th pick of the draft, it tapped Ernie Grunfeld of Tennessee, a small forward.

Bentsen soon signed a six-year contract for $900,000 to $1 million. The Bucks wanted to pay Johnson less, but Johnson reminded them of the offer made and then withdrawn by the Denver Nuggets the year before. The Bucks, fearing an antitrust suit from Johnson, gave him what Denver originally offered—a six-year contract for $1.2 million.

Benson was an instant disappointment, Johnson an instant success. Johnson seemed to have everything in perspective.

“The first time around,” he said, “there were a lot of things I had to learn. In college, maybe only two or three times a season I faced a player who gave me trouble. Being a pro, potentially every player can give you trouble every night. You can’t disregard anyone. You always have to play intense defense.”

Johnson is more than a basketball player and a philosopher. He seems to have the magic touch that tells people what the right thing is and when and how to do it. For example, in the summer between graduation and the pros, he worked with youngsters in Los Angeles. His accomplices included Kermit Washington, Pat Haden, and John McKay, Jr.

“We’d go to the parks and give two-hour clinics,” said Johnson. “We’d work with the kids and talk about basketball and life. We go to elementary and junior high schools and give one-on-one exhibitions. I think it’s important for athletes to do things like that. When I was young, Walt Hazzard of UCLA came to our school. He was very congenial and made a big impression on me.”

Johnson’s attitude hasn’t changed. He signs autographs endlessly. No matter how many people surround him, he is patient, always smiling, always chatting. “It’s just being human,” he said. “They’re there when I go out for warmups, and they’re there after the game. They want me to hold hands or slap hands as I go by. I slap as many hands as I can. Something like that can mean a great deal when you’re 12 or 13 years old.”

So there he is—Marques Johnson, superstar. He’s skilled, handsome, intelligent, responsive to his coach and public. He seems to have everything, except the salary that should go to a player of his excellence. For the next four years, his original contract is in force. It pays him $200,000 a year when many lesser players earn more and when superstars on his level earn two or three times as much. In short, he is stuck with a long-term contract.

Ted Steinberg of Los Angeles, his friend and new agent, sympathizes with him. Steinberg is an expert on contracts because he is the agent for Alex English and other players. “With a long-term contract,” said Steinberg, “you’re betting against yourself. Kent Benson won that bet. If Marques Johnson were a free agent, he’d earn as much as anyone. There’s no reason why he couldn’t easily earn $800,000 a year. He has the opportunity to be the O.J. Simpson of basketball.”

He expects the contract to be renegotiated.

Johnson’s agent was Donald Dell, the Washington, D.C. lawyer who represents athletes in many sports. Dell’s philosophy is that a deal is a deal. As David Falk, an assistant, said:

“We have never renegotiated a contract in pro basketball. Our office represents a number of players. We have to have a pretty strong reason to recommend that they put their names on a contract. And when they do, we want to honor that commitment.”

Should the Bucks offer to renegotiate? It’s a two-way street. When Dave Meyers has been injured, as he has been so often, the Bucks pay him in full. Meyers’ contract requires them to. Should Johnson be injured, he would have to be paid in full, too. Jim Fitzgerald, who owns the Bucks, isn’t sure what is right.

“We want Marques to be happy,” said Fitzgerald. “We want to protect him, wrap him in a warm blanket. We love him. For us to renegotiate is not unheard of, but that kind of discussion is premature at this point in a six-year contract.”

Tracy Dodds of The Milwaukee Journal tries to put it in perspective. “Johnson has said nothing about not being happy,” he said. “His performance is exemplary, his attitude great. He works as hard as a man can work , always pushing himself to improve. He has great pride. He can’t help himself. What a prize the Bucks have. What a price for that prize.”