[Several years ago, while working on two of my basketball books, I considered contacting NBA Hall of Famer Hal Greer. I was advised by several of Greer’s old friends, including his former college roommate, that he’d never answer me. One reason owed to his health. Greer was still recovering from a serious stroke that impaired his speech. The other reason, or so I was told, was Greer had grown bitter over the rough treatment that he’d received from teh 76ers and the NBA after his playing days. Greer wanted to coaching job in the NBA. He got no job offers, just cold shoulders..

Greer never answered my requests for an interview. But I was heartened to see a few years later, Greer reemerged from his self-isolation to relive the good and the bad of his NBA career. Maybe time had healed some of the disappointment.

In this article, pulled from the March 3, 1974 issue of the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Sunday Magazine TODAY, Greer begins his quest to land an NBA heard coaching job. He’s prepping as the brand-new head coach of the Cherry Hill (N.J.) Rookies in the Eastern Basketball League. Among his players is Luther Rackley, whom the blog featured just yesterday.

The 37-year-old Greer arrived in a league that was in sorry shape. “Ever since the inception of the maverick American Basketball Association in the mid-1960s,” wrote Dick Weiss of the Camden Courier-Post, “the Eastern Basketball League has been a wilting flower, dying for lack of sunlight.” Al Haas, a staff writer with Philadelphia Inquirer TODAY, picks up the story. Haas would move on to become the paper’s longstanding automotive columnist.]

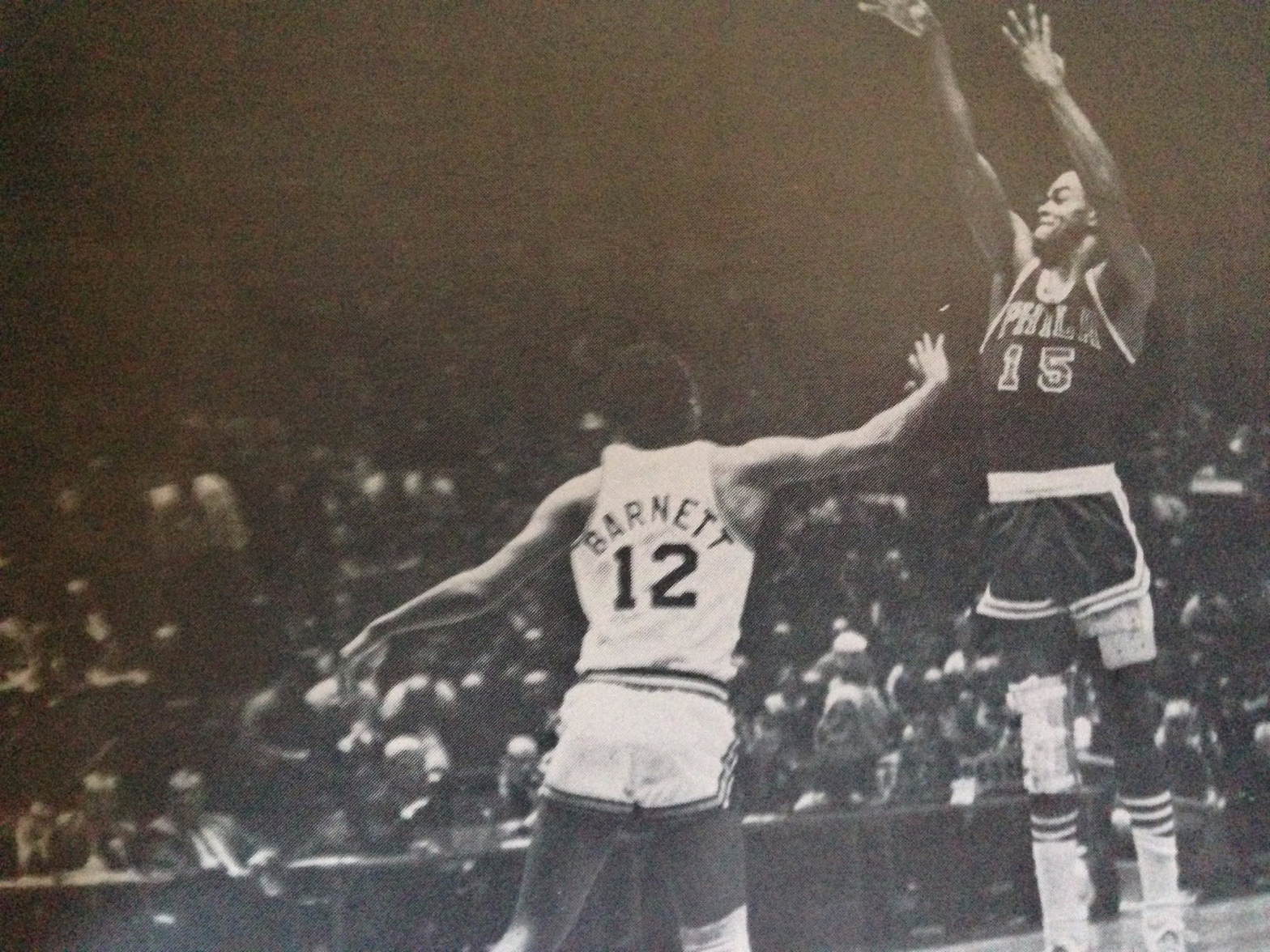

It is a winter night in a cold cavern called the Cherry Hill Arena. Former big leaguer Hal Greer, one of the finest basketball players ever to pull on a Philadelphia 76ers uniform, is making his homecourt debut as coach of the minor league Cherry Hill Rookies. The 265 people on hand for the occasion comprise a modest archipelago of humanity in the sea of nicked seats.

Things are not going well on the court, and Hal Greer is reacting like a composer listening to an orchestra brutalize his score. He animates the sidelines with his anguish and frustration. His actions seem to symbolize the deeper disappointments basketball has dealt to him and the men around him.

An intercepted Rookies’ pass finds him driving his head up and down like a piston, as if he is pounding it against a table top. Another mistake yanks him to his feet, elicits a wince and leaves his head shaking. A questionable call brings him back up, the initial outrage on his face dissolving into the open-armed gesture of one beseeching justice.

All the time, an undertow of big-league experience drags at his legs. He has this compelling urge to jump in there and “ease the play along a little,” to do it the way 15 years in the National Basketball Association tells him it should be done.

The ball bounces near him a couple times, and he fights this crazy impulse to reach for it. The game ends in a Rookies defeat—the teams 10th in 11 starts—and Hal Greer walks slowly toward the locker room, his head bowed.

This is not the way Hal Greer had wanted to start his professional coaching career. Not with a defeat, not in the near anonymity of the minor leagues. He had wanted to coach the 76ers when it was ordained last year that his playing days were over. He had wanted to stay in the limelight he had known so well.

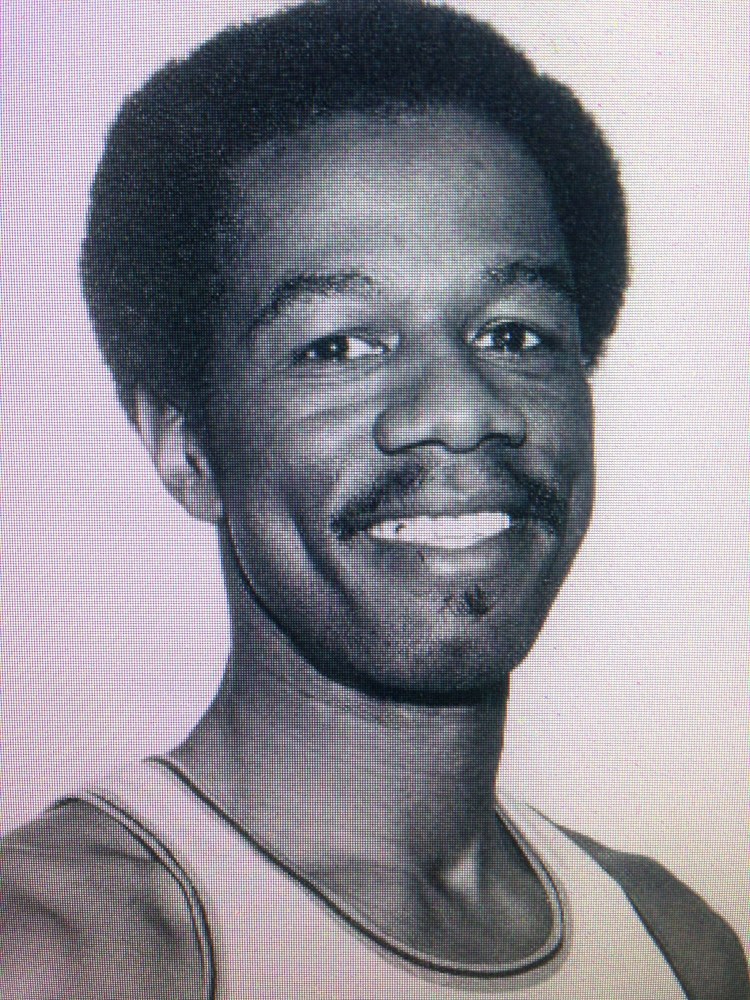

And Hal Greer did know the limelight. During his incredibly long career in the NBA, The Great Guard Greer set a league record by appearing in 1,224 games. In the course of those 15 seasons, his trademark jump shot and hustle were fixtures at 10 All-Star games.

Hal got a good taste of fame and success in those years, especially in 1967, when the 76ers won the championship. He became accustomed to the cheering multitudes in places like the Spectrum and Madison Square Garden. He got used to people shoving autograph books in his hand. He got in the habit of being paid $135,000 a year to do something he loved to do.

Then all of a sudden, last March, it was over. The limelight and the big salary were gone. So was his beloved profession. His dreams of coaching the 76ers, or any other NBA team, were lying in his head in a thousand pieces. He was 37 and jobless.

Eventually, Hal Greer found himself in a minor league called the Eastern Basketball League, making a few hundred a week in the company of a lot of other men with fissured dreams. The EBA, or Eastern League, is really a reservoir of splintered dreams. It is filled with men who have found disappointment in a game they love.

For some, the disappointment lies in being released from big league teams they are convinced they were good enough to stay on. For others, particularly the recent casualties of the big-league rookie camps, it resides in the belief that they are good enough to play in the big leagues, but haven’t been given the chance. For still others, the hurt derives from the realization that as good as they are, they aren’t quite good enough to play big league ball.

They are, in short, men who dream—or have dreamed—of playing in the majors but are not doing so. This is not to suggest that the Eastern League is filled with tragic young men moping about, uttering monologues on the cruel and capricious nature of big-league basketball. Far from it. They are having fun playing a game they love against spirited, talented competition. This is true of the frustrated big-league aspirants as well as the men without NBA pretensions.

But there is, beneath the surface, joy of doing something they do well, an undercurrent of disappointment and frustration. And what emerges from this deep, sub-surface stream is a commentary on what big league basketball can do to men.

Consider a few of the Cherry Hill Rookies:

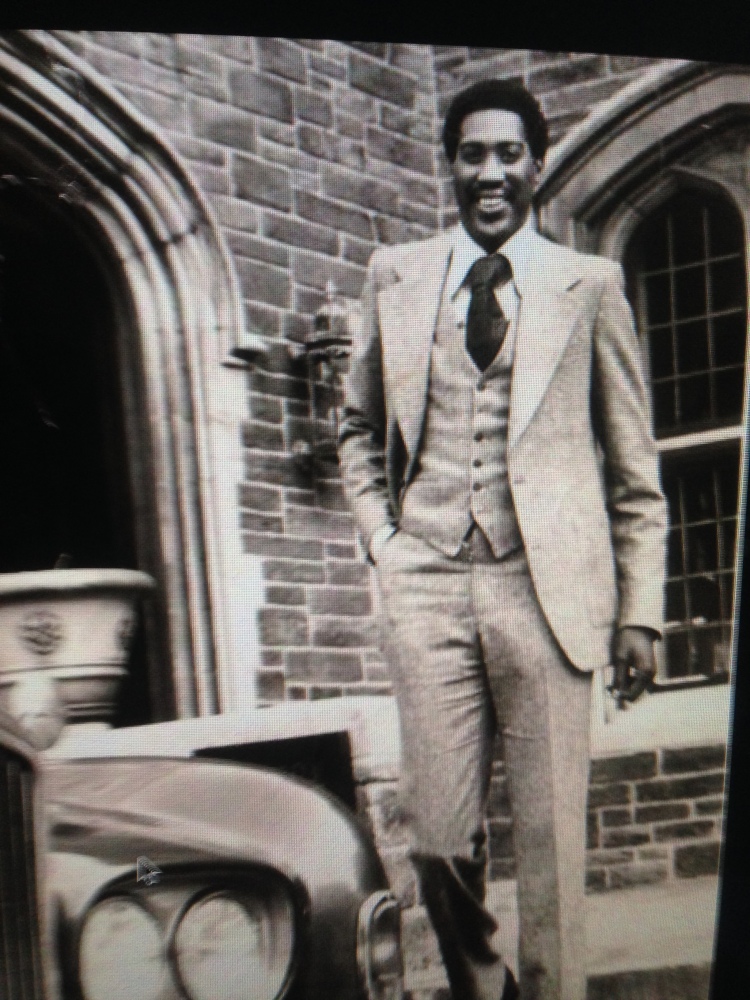

Luther Rackley, the Rookies’ 6-foot-10 center, is a handsome man of 27 who came to the Rookies from the 76ers after five rather confidence-crushing years in the NBA and American Basketball Association. He started out well enough in Cincinnati, averaging 7 points a game as a rookie. The long trauma began, according to Rackley, when then-Cincinnati coach Bob Cousy began envisioning him as another Bill Russell, the defensive genius who became a legendary center for the Boston Celtics.

“I didn’t want to be another Bill Russell, I wanted to be Luther Rackley. I thought I was doing a damn fine job as Luther Rackley.”

Cousy obviously didn’t; he publicly called Rackley “a mediocre center.” (“That really hurt. I was never mediocre!”)

Dealt to Cleveland, Rackley had perhaps his best year. He was then traded to the New York Knicks. He started some games for New York, and things seemed to be going right—for a while. Then the Knicks, heavy on new players whose [no-cut] contracts banned dropping them from the team, asked him to play in the Eastern League on full salary “until something opened up.”

Rackley didn’t want to “spend the rest of my life in the Eastern League.” He wanted to play major league ball. So, he sold his contract back to the Knicks and jumped to the ABA’s Memphis team. At Memphis, his salary dispute culminated in his being cut.

He was picked up by the 76ers about the time his wife let him go. and came to Philadelphia last October “with my head on sideways.” “Just about the time I was getting my head and game together, the Sixers cut me,” he recalls. “By this time, I’m really screwed up. I can’t even tie my shoes . . . “

But although his confidence was shaken and he was disgusted with big league basketball, Luther Rackley still wanted to play, still believed he could play. And so, he came to Cherry Hill.

“I had to prove to myself and others that I can still play basketball. I’m not saying I’m a superstar, but I know damn well I can play in the NBA. My primary goal is to get my confidence back, to prove I can be a constructive athlete.”

If this is not to be proven, Luther Rackley will have to know it can’t be proven. No one is going to tell him. “I have to learn I’m not useful,” the big man says quietly. “Once I’m satisfied, then it’ll be over.” What will be over, he suggests, is his effort to prove himself worthy of the big leagues, not his basketball playing.

“Basketball gets into you, you know?”

****

Barry Yates, a 6-foot-7 forward, is a bit like Rackley. He, too, was cut by the 76ers after playing in the NBA for a while. He, too, was disgusted with pro basketball.

Yates came out of college in 1971 and got himself a berth on the 1971-72 Sixers. He also got himself a spot on the 1972-73 team—or so he thought. “I was the number three forward,” he recalls. “I had played adequately (during the preseason) and felt fairly secure about the whole thing.”

Then he tore a chest muscle. He was out a little over a week with the injury, returning to active duty for the last preseason exhibition game. Coach Roy Rubin, who had told him to “lay out and don’t worry” when he hurt himself, was suddenly singing a different tune when he put him in that exhibition at Buffalo: “’You have to do it tonight,’ he told me.

“Well, I had a terrible night at Buffalo. I didn’t shoot well . . . The whole time I was in there, it was in the back of my mind he was going to cut me. And he did.

“I was disgusted. I probably could have played in the EBA and worked my way back up, but I was so disgusted with the whole thing, I figured the heck with it. I figured it was time to look for something else to do.’

“Something else” for accomplished pilot Yates was a crop-dusting stint in the South, where he spent the growing season flying over soybean fields at a speed of 100 MPH and an altitude of five feet.

He returned to this area when the season ended, and Rookies owner Rich Iannarella started asking him to play for the team. He finally decided to take another shot at basketball and the big time, knowing “very few ever make it up from the EBA.”

“I’d go up if they called me, but I don’t really expect them to—even if I play well.”

Slowly, Yates has been getting back in shape, retrieving his shooting gifts and rediscovering what it is about this game he likes so much. “I guess it’s like anything else,” he says of basketball. “It’s a way to express yourself.

“You get out there and you feel it,” he continues, adding that he gets the same kick from basketball he gets from crop dusting. “In crop dusting, you’re moving all the time. Dodging trees and wires, and basketball is the same way—you’re moving all the time.”

****

Sterling Wright, a 1973 Lincoln University graduate, is a 6-foot-8 forward who thought he had a “bright future” with the New York Nets after attending their rookie camp. The Nets signed several no-cuts over the summer, however, and the young shooter’s future dimmed considerably.

Released by the Nets, Wright came to Philadelphia, where the 76ers took a perfunctory look at him and told him they weren’t interested, either. “I got to play three minutes out of a two-hour practice,” Wright remembers. “It was crazy . . . I guess he (Coach Gene Shue) was just about ready to make the final cut, and I would have wrecked his system.”

Despite being given the gate, Wright is confident he was good enough to make that team. (“I know I’m comparable to Steve Mix in talent, and Steve is starting and doing a hell of a job for them.”) At the same time, he is willing to admit he has deficiencies as a player.

And so, it was that he came to Cherry Hill—“to improve my game and prove myself.”

****

Ben Warley, a 6-foot-8 forward and coaching assistant, is a lot like Hal Greer. Like Greer, he spent a lot of years in the big leagues, with teams like Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Denver. Like Greer, he is a lean, well-conditioned man who neither looks nor plays like he is 37 years old. Like Greer and some of his teammates, the game has handed him a disappointment. His came three years ago, when a youth-minded Denver coach let him go because of his age.

“I felt bad about it. I could have accepted it if he had said I couldn’t play. But he never complained about my playing.”

He remembers vainly reminding the coach he was still “thin as a straw, quick as a gazelle, and had my eye.” He remembers being replaced by some kid “who couldn’t even get in his jock.”

After a year, the bitterness subsided and he resumed his game in the Eastern League—last season with Wilkes-Barre, this one with the Rookies. Warley sees his player-assistant coach role with the team as a way to get coaching experience and keep active. (“I can’t sit around. I’ve got to keep moving.”) It also can be seen as an effort to prove something.

You get the feeling this old pro does have something to prove when you watch him at practice. The way he stuffs the ball in the basket instead of just tossing it up during the three-man weaves, for example. There is, in the authority of that unnecessary dunk, a clear message: “I can still cut it.”

Underlying these reasons for playing, of course, is Warley’s essential feeling about the game. “I do love the game very much. Sometimes, my wife thinks I love it too much. My wife says I’ll play until they have to wheel me to the foul line. She understands how I feel about this game—and we don’t have any misunderstandings about that.”

Ben Warley smiles when he recites his wife’s prophecy, and I am reminded of a Tennyson poem in which a white-haired, post-voyage Ulysses declares: “For my purpose holds to sail beyond the sunset, in the baths of all the western stars, until I die.”

For men like Rackley, Yates, and Wright, who believe they are good enough to play in the majors, the disappointment intrinsic to playing in the Eastern League is compounded by the frustrating realization that they may never get out of it. The whole time they are trying to prove they can function in the NBA or ABA, they are deviled by the knowledge that the odds are against them being called up. Since the end of last season, only three Eastern Leaguers have been summoned to the majors.

The reason, as Hal Greer suggests, is that there is simply “little room at the top.” What room exists is much more likely to be filled by a promising college draft choice than an Eastern Leaguer who has had a crack at the big time and didn’t stick. As Rookies guard Fran Dunphy puts it: “Once you get sent down, you have to show a lot to come back.”

It is also true, of course, that only a minority of the Eastern League’s operatives have clear-cut big league ability. Most of those who think they have it or are really marginal big leaguers or less. For them, the Eastern League will ultimately reveal itself as a $75-a-game dead end. For them, the graceful game they love will ultimately yield up another disappointment.

It is to these sorts of men that Hal Greer brings a compatible state of affairs. He, too, has something to prove—that he can coach. He, too, has a dream—to coach in the NBA. He, too, has had his disappointments.

“I was a little disappointed when I didn’t hook up with the 76ers,” he reflects. “A little disappointed. But it was just one of those things, one of those things that happen. But I was a little disappointed. Yeah, I was a little disappointed.”

For Greer and the other former NBA players on his team, there is little in the Eastern League to remind them of halcyon days. The tri-state league consists of seven teams with low budgets and a history of losing money. (The Cherry Hill team is no exception to this tradition. Started last fall by the 46-year-old Iannarella, who quit a front office job with the 76ers to be his own man, the team has been losing at the gate as well as on the court.)

The amenities that accompany these financial realities leave former big leaguers like Greer and Rackley in what Iannarella calls “a state of shock.” Eastern Leaguers don’t play in Madison Square Garden to screaming throngs. They sally forth in Cherry Hill Arena and high school gyms before laryngitic gatherings measured in the hundreds. They hold full-time jobs as teachers and salesman while practicing weeknights and playing on weekends—for about $75 a game, providing, of course, they show for it.

In the Eastern League, an away game doesn’t mean a jet plane ride, a room in the best hotel, or a steak-permitting $19-a-day meal allowance, as it does in the NBA. It usually means getting to Hartford or Scranton or East Orange any way you can. If you’re lucky and play for a team like the Rookies, you get to ride to the away games in the back of a Ford van with nine other large men. In the case of the Hartford trip, that translates into eight hours of kneesies.

It is to this alien environment that old pro Greer brings his unproven talents as a coach. Although a novice, he comes on the job with a significant asset. He has the friendship of some of these men and the respect of all.

“He was such a great pro,” Fran Dunphy observes with typical reverence. “He was what all of us would have liked to have been.”

In the wake of that latest Sunday loss that had left him so frustrated, Hal calls three weeknight practices. The first is on Wednesday night at South Philadelphia High School. He laughs as he walks into the scarred little gym. “Is this the place?” he asks incredulously, as the kids from the just-ended CYO game cluster around him for autographs. “Is this where we practice?”

After getting over the shock, Hal proceeds to drive his team mercilessly. Three-man weaves five times up and down the court at full bore. Laps (penalty runs around the court) if you miss the layup.

Greer doesn’t just prescribe these rigors from the sidelines, he joins in them. When they are one man short for scrimmage at the conclusion of this two-hour ordeal, Hal becomes the 10th man. They scrimmage until the janitors chase them off the court.

“Wowee,” yells a sweat-soaked Greer, as he sinks into a restful couch. “This is a lot tougher than golf. I’m going home to bed. Tomorrow, I’ll be stiff as a board.”

This is his first hard run in nine months, and it has left him exhausted and exuberant. This is the way Hal Greer loves to suffer. “I’m going to give this all I can,” he vows. “If the players do the same, we’ll be all right. The talent’s here. Our record shouldn’t be 1 and 10. No way at all.”

Greer’s zeal, his belief that the team can be turned around and his determination to do it, begs a response from his players. “How can you not put out for a guy like that?” asks Barry Yates. The Greer influence seems to revive the spirit of this oft-beaten team. Winning looms as a distinct possibility, and that is a delicious thought. “Everybody (on the team) wants to be a winner,” Fran Dunphy observes. “Losin’ stinks.”

The team gets its first chance to put its new spirit to work at the following Sunday’s game against the Garden State Colonials in the arena. The Colonials, an East Orange club which is arena-wise enough to bring gloves to warm the players on the bench, is not about to aid and abet a Rookie renaissance, however. They come on strong in the second half, stirring old reflexes in Coach Greer. (“That old feeling comes down on you. A couple times, a ball would bounce toward me and I had the urge to grab it.”)

In the end, however, Greer’s intervention proves unnecessary. Down 18 late in the game, the Rookies stage an exciting comeback and somehow pull it out, 107 to 104. The victory is an obvious source of joy to the EBA’s leading loser. Sure, it is against one of the league’s weaker teams. But still, maybe it is a beginning. Maybe Hal has begun to turn this thing around.

You hope he has. You can’t help thinking that men who love this game this much, who play it this hard, deserve something more than 75 bucks—and disappointments.

Bonus Coverage: On August 30, 1974, the Camden (NJ) Courier-Post ran the following:

The Cherry Hill Rookies will never dribble an icy basketball in the Cherry Hill Arena again—the Eastern Basketball Association team has been sold, a new playing site has been located, a new coach hired, and ex-Sixer Al Henry has been added to the roster.

Richie Iannarella announced Thursday the Rookies were sold as a “total basketball package” to a group of Cherry Hill civic leaders who planned to relocate the team at Cherry Hill West High School this winter. Iannarella did not disclose the purchase price.

And Hal Greer never coached in the NBA.