[Mention Red Auerbach, and most in-the-know basketball junkies will rhapsodize about his nine NBA championships in the 1950s and 1960s as coach of the Boston Celtics. The word “genius” usually enters the conversation quickly as well as the explanation that Auerbach brought Bill Russell to Boston and shrewdly tapped into his new center’s dominant defensive skills to revolutionize the NBA.

Likely to be overlooked is the fact that during Auerbach’s NBA reign, he was equal parts loathed and respected by his colleagues. NBA president Maurice Podoloff, for example, later leveled that one of his major regrets was that he didn’t crack down on Auerbach. “He was an able coach, always the quickest to see the faults of any suggested changes in rules. But he was an abrasive man. When he’d light his victory cigar in those televised games, I always wished someone would shove it down his throat.”

In fact, many of Auerbach’s contemporaries would debate affixing the tag “genius” to their bitter rival. As many contended, Auerbach got lucky with Russell—and, with a scoff, the rest is history and Red’s inflated opinion of himself. Such scoffs probably go too far. But in this article, from the February 1956 issue of SPORT Magazine, writer Irv Goodman profiles Auerbach, pre-Russell, or when many in the business considered him overrated and born to lose the big game. Shocking? Well read on. Goodman does a masterful job.

A quick note for you journalists out there. Imagine trying to get Goodman’s run-on lead past an editor today. Times have changed, but Goodman’s story stands the test of time. Really good stuff.]

In his textbook Basketball, For the Player, the Fan and the Coach, which has sold more copies than any other book on the subject and about which he is uncommonly talkative 38 months after publication, Red Auerbach reveals, perhaps without knowing it, why he is such a controversial yet popular, often fined yet often imitated, misunderstood yet successful coach. The provocative coach of the Boston Celtics wrote, among others, the following maxims:

“When a player notices an official’s indecision on an out-of-bounds ball, he should run over and pick it up with the full confidence that this is his.”

“Use the hands to hold and block cutters under the basket.”

“Grabbing or pulling the pants or shirts of the opponents can be very aggravating.”

“A smart team will take advantage of the homecourt and the home fans. In fact, they may make moves to stimulate crowd reaction in their favor.”

“Very often slight movements of the body are used to distract the opposing foul shooter.”

Question officials’ decisions, especially on the homecourt.”

“When your opponent makes a good play, don’t congratulate him, merely mention that he was lucky.”

The purest and the guileless among the basketball addicts raised an understandable ruckus over Auerbach’s guide to better basketball. It’s bad enough, they complained, that he indulges in these tactics himself, but is this any way to teach basketball to youngsters? The man is peddling deceit and artifice, they charged. A newspaper detractor noted that Auerbach warned never, never to incur a technical foul “regardless of the cause,” yet he gets more technicals (and fines) on the bench then any player ever received on the court, often for silly cause. He is the most-fined man in pro ball, his critics claim, and it serves him right.

All of which, if dashed with temperance, is undoubtedly true—except that it is far from being the whole story. Neither Auerbach nor the demands of professional basketball can be explained away so neatly. There can be little argument that Auerbach is a hothead on the bench, a bit of a con man, a foot-stomper, and a referee baiter who holds firmly to the conviction that you’ve got to beat the other fellow any way you can before he beats you any way he can. But Red is also a fellow who thinks he is being persecuted (“they fine me to teach the others a lesson”) in a thankless job. There is substantial evidence that he is an actor and a shrewd clubhouse lawyer who finds it difficult to resist a dig. Yet there are also signs that he is a lonely man in a lonely business. He works in a tough sports town with a tough press. Before you can justly rap him, you must know him—and to know him, you have to understand the small wiles and narrow ways of big-time professional basketball.

It is probably true in other sports, too, but one clear impression of the National Basketball Association is that its coaches are committed to an unending battle based on the theory of the survival of the fittest. The pro game is an arena in which a coach is either quick or dead. Clair Bee, an experienced and respected college coach for many years, died the death of the unprepared in the NBA because other coaches pounded him with back-alley tricks. The collegiate cut of basketball coaches, who mess with teaching and training in their work, don’t stand much of a chance in the pros. To be a successful NBA coach, you have to be a “bench coach,” a fellow who thinks quickly under fire, who can take advantage of any opportunity, who can instinctively spot a weakness in a player, coach, referee, or timekeeper, and who doesn’t bleed easily.

Some NBA coaches aren’t even coaches in the traditional sense. Charlie Eckman was a referee who didn’t play or coach basketball before he was given the hot spot at Fort Wayne. His success with the assignment is credited to his cheerleading tactics on the bench, his sharp tongue which can be heard all the way out in the lobby, and his memory for names (a knack which enables him to say, rapidly and flawlessly, “Hutchins in for Yardley “).

Eddie Gottlieb has been coaching pros for 30 years. What qualification he had for the job, no one seems to know, or remember. But Eddie owns the Philadelphia Warriors, so he made himself coach. He believes a coach is really a manager and that you can’t teach pro players anything, that you can only handle them. This year, Gottlieb is letting George Senesky, a former player, do most of the work, but Eddie is still the coach.

Some people figure the same is true for Lester Harrison of the Rochester Royals. Like Gottlieb, a promoter, Harrison officially turned over the coaching job to Bobby Wanzer before the start of the season and promised to keep off the bench. But before the season had started, he broke his promise. Not only has he been on the bench second-guessing his playing manager, but he bounces out onto the court about as often as his No. 6 man, protesting calls, yelping at referees, calling timeouts, and haranguing the opposition.

Arnold (Red) Auerbach, who had little coaching experience when he joined the league in its first year, 1946, with the Washington Capitols, travels in this company. Red, who is 38 years old, likes to think of himself as a teacher of basketball. He is proud of his many invitations to lecture at coaches’ clinics. He says he spends long hours instructing his players on fundamentals. He uses set plays in a league that relies mostly on a freelance offense. He wrote a book.

Others in the league, however, think Auerbach is a bench coach, a good one by the existing standards. “Red’s come a long way in this league,” one of them said, “and he’s been lucky. With all the raps against him, he’s been able to hang on.” An NBA official, picking up the same theme, suggests that Auerbach’s success comes from his performances on the bench and not from his work in the practice gym.

“Look at his record. He’s had three of the greatest players in the league (Bob Cousy, Ed Macauley, and Bill Sharman), and he’s never won the title. But three players don’t win NBA championships. The Celtics lack rebounding height, Sharman is weak on defense, Macauley gets tired. But the fans apparently don’t know this, and that’s what makes it so surprising that they haven’t gone after his head. It must be that Red’s colorful work on the bench helps him with the fans. It certainly doesn’t help him with the newspapers.”

The Boston press is almost unanimously against Auerbach. “Seven of the eight papers in Boston don’t like him,” one pro veteran pointed out recently, “and no matter what you think of Red personally, there must be some reason for it. He’s so . . . enthusiastic, so . . . determined to win, that once in a while he goes off the deep end.”

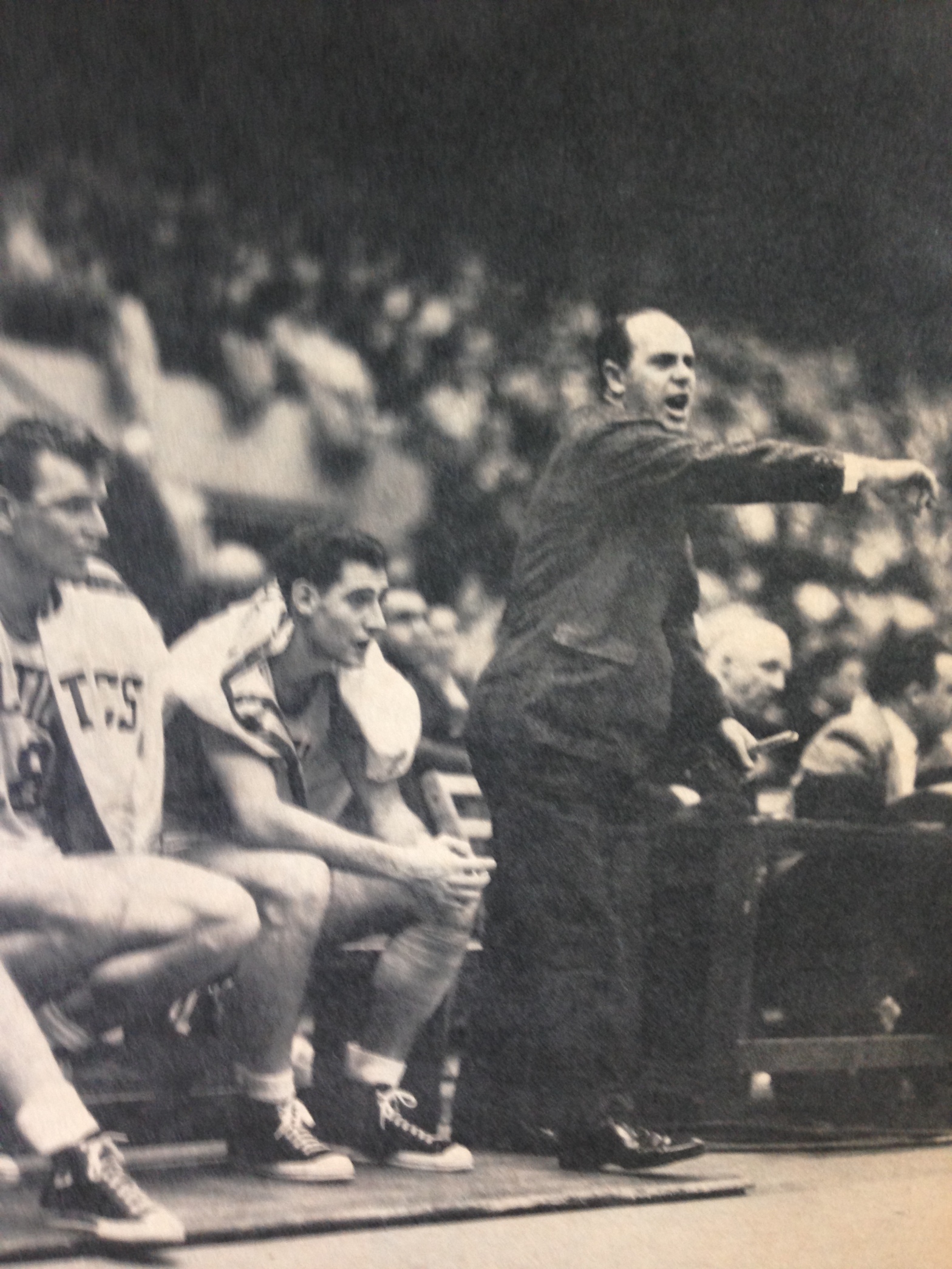

These references are to the hot temper Auerbach exposes to the view of the paying customers (and, when he gets the chance, to the television freeloaders). His moves on, and in front of, the Boston bench are classics. He lunges upward and outward from the bench on most of the calls against his team. His face, hardly a smiling countenance in the best of situations, contorts into a snarl as he rasps his pet phrases at the referees.

Familiar, too, is his habit of storming over to the scorer’s table for a suspicious look at the records, or flicking cigar ashes at the feet of the officials. It requires little more than a palming call against Cousy for the balding, Brooklyn-born ex-redhead to go into his act, which, in milder moments, consists of hands raised to the rafters, a loud foot stop, a furtive turned to the stands for sympathy, a deliberate stride toward the referee, a martyred return to the sidelines at the urging of the official, a determined jam of his cigar into the side of the mouth and, with hands on hips, a heavy sigh of utter disbelief that such injustice could be taking place here and now—and to him.

Red’s sideline shows have had some noteworthy consequences: They have cost him money, they have cost his teams a few games, they have helped win a few others, and they have made his court conduct generally suspect. “It is a pretty good guess,” said one coaching colleague, “that much of Auerbach’s temper is a put on. Otherwise, he would have cracked up by now.”

It is probably true that Auerbach simply puts on a show in many of his tirades. But it is also true that a loss, or even an adverse call, brings him to the emotional boiling point. One of Red’s $100 fines followed a wild game against the Minneapolis Lakers on a national television hookup last season. With the game tied, the referee called a foul against the Celtics at the final buzzer. It was one of those tough calls that some observers believed could just as easily have gone the other way. But the ref awarded the Lakers a foul shot. With Auerbach breathing fire and cigar smoke around the scorer’s table, and the audience responding with a cascade of boos, the Lakers sank the foul and won the game.

Such a loss sits easy with no man; with Auerbach it was a crown of fire and brimstone. A man who needs time in solitude to lick his wounds, Red made the mistake of submitting immediately to a postgame television interview. His venom still at flood level, Red “spoke my mind” to the camera with the red light. “My remarks were strong,” Red admitted afterwards. “but they weren’t abusive,” as some reports had claimed. “I said the call was stupid. It was.”

After the game, NBA president Maurice Podoloff told the press there would be no fine. After Auerbach’s television performance, Podoloff changed his mind.

A frequent Auerbach complaint followed that fine. “I asked for a hearing and never got one. Once I protested a game because of a foul call, and it was granted. So, the referee doesn’t even show up for the hearing!”

Podoloff’s pat answer was that Auerbach wants to win and that the league president wants to protect his officials. “Referees have a hard time of it,” he said, “and when one of my men makes a courageous call in the face of anticipated protests, I have to go with my man. After all, it is a matter of judgment, and a coach can’t legitimately protest that.”

The way Auerbach has it figured, his run-ins with referees are due to his knowledge of the rules. “I try to talk rules with them,” he says, “because I want to get some consistency out there. Let every ref call a charge a charge. Some won’t call walking because it doesn’t affect play. But some will. It’s the same with technical fouls. We have a rule there can be no talking by coaches to the refs on judgment calls. But some refs you can talk to and some you can’t. If we have a rule, it should apply for all.

“I know some people criticize my arguments with the refs. But that’s the way the sport is. Who in basketball is tougher than Adolph Rupp or Ed Diddle? Does that make them bad coaches? A club must feel its coach is supporting them. If I think a ref blew one, it’s my job to argue. It gives my team confidence. When I get clipped with a technical, it’s right, but that doesn’t mean I’m sorry.

“I’ll say this much. We have referees who are among the best that are available. (The way he said it, the key word was available.) The problem is in the game. It’s the toughest to officiate, and I know that as well as anyone. I was a ref, too. What gets me mad is the inconsistency of the calls. Once a ref called a technical on our bench. I asked him who it was. He said Fred Scolari. I told him Scolari was back at the hotel sick. Their technical stood. Refs can’t have rabbit ears. They can’t go shopping for technicals. They have enough trouble calling the ballgame.”

A couple of seasons back, Auerbach had an argument with Al Cervi, coach of the Syracuse Nationals, and ever since some people have figured they were working on a running feud. It was at the time of the All-Star game, and Auerbach didn’t want Cousy, who had a bad leg, to play in the game.

“Al was coaching the game and naturally he wanted to win it,” Red explained. “So, he asked Cousy if he’d give it a try. What was Cooz going to say? If it had been a regular-season game, he wouldn’t have played as much as he did. I had no argument with Cervi. A reporter brought it up. I just felt that if I had been the coach, I wouldn’t have used Cousy because he is my player.”

Why has talk of the feud continued? “Because in this league, they like to develop rivalries.”

The Boston press has always been willing to help Auerbach along, although it is fair to assume that the redhead would have made it all on his own, given enough time. There has been talk of dissension on the Celtics since the three big stars began playing together. Some writers claimed that his players don’t hold Auerbach in the highest of esteem. But outside the sports columns, there has been little substantial evidence of any disturbance. The biggest story about troubles within the Celtic family followed a press luncheon in Boston. The Celts were in a slump, and Auerbach was asked what was wrong.

“You can’t say nothing,” Red explained later. “There are eight papers in town, and with no pro football, they cover basketball and hockey all winter. That means the Bruins and the Celtics. Somebody is always watching, looking for an angle, because they have to produce copy every day. We’ve had games where 12 local reporters were covering. Since I’ve been in Boston, I’ve taken the attitude that since they are looking for an angle, I’ll give them an honest one or none at all. You can’t get into too much trouble if you tell them the truth. It would be much worse if you lied.”

So, Auerbach stood up at the luncheon and said that the Celtics trouble was that Macauley wasn’t tough enough, that Cousy was throwing the ball away, and that Sharman was taking bad shots. “I included some other players, too. I said Bob Brannum wasn’t hitting, for example. It was all said in a matter-of-fact tone. I wasn’t blistering anyone. I was giving them an honest answer to their question. But the reporters grabbed the three big names and tried to make something big out of it.”

That day’s stories were about Auerbach “blasting” his stars. The follow-up stories had his stars blasting back. Some of the reporters reached Cousy before he had had a chance to hear about Auerbach’s little speech. When they told him what Red had said, in their own words, Cousy was caught off guard. He said he was surprised to hear it, but “if that’s the coach’s attitude, we’ll have to straighten it out.” It was a good answer, but the sensation-hungry newspapers blew it up into headlines saying (1) that Cousy would be traded, (2) that Auerbach would be fired, and (3) both.

The hot story could not hold its headline flare. Two Celtic players—Jack Nichols and Don Barksdale—had been at the luncheon and confirmed Auerbach’s unvitriolic observations, at least to the rest of the squad. Nichols, commenting on the incident recently, recalled that he had been shocked at the reporters’ reaction to Auerbach’s speech. It had been a common candid talk, Nichols remembered, and had no tone or implication of blasting any Boston player.

The day after the luncheon, Auerbach talked it out with Cousy. “I explained everything to Bob, and we straightened it out. I didn’t apologize; I didn’t expect him to. There was no need for either of us to be sorry. We both understood the papers wanted an issue, and that was why they said I blasted Bob. After one day, there was nothing around our club about the incident, no reminders, no leftovers, no bad feelings. I never blasted a player of mine in public. My job is taking after the other guys.”

Cousy, who shows no signs of any feud with his coach, admits that Red goes overboard once in a while. “The fellows on this club like his guts,” Bob said, “even though his outbursts are sometimes ill-advised, especially when he draws one of those technicals that hurt us. But he’s working like we are, to win, and we know it and appreciate it. He doesn’t give any of us the dirty jobs that have to be done. He handles them himself.”

Cousy explained further that Red’s tirades are not always unthinking outbursts. “He’s always thinking, no matter what he does out there. He has a reason for just about everything. A couple of years ago, he started rushing in a big man when a little man had a jump. He would have the little man stop to tie his shoelace to give us enough time for the substitution. The other coaches laughed at this at first, but quickly adopted it when they saw it worked. They used it so much, the league finally had to rule it out.”

In its attacks on Auerbach, the Boston press inadvertently has created something of a Frankenstein monster. A number of their charges against the ogre have exploded in their faces. Once, in reporting what was supposed to be the hot poop about a sure-fire Celtic-Knickerbocker trade, one writer found himself compelled to compose his story this way: “Dick McGuire will be listening to coach Auerbach’s nonsense . . .” McGuire is now in its seventh season with New York.

Two years ago, when Cousy had a rib injury and Boston was losing, the Boston writers announced that the league, now better balanced, had caught up with a fancy dribbler and his dribbling coach.

Tom Carey, who writes for the Worcester Gazette, has it pronounced distaste for the Celtic coach. “Much to my sorrow, he (Auerbach) will return to the Hub as chief of the Celts,” Carey once wrote after Boston owner Walter Brown had signed Red to another contract. “One thing is for sure, Brown and Auerbach are as neighborly as first cousins. Red can do no wrong with Mr. B., who, by the way, rates the redhead as the finest coach in the NBA. Merely a matter of opinion, Walter. For my two points, Auerbach is the most-overrated coach in the business.”

Red’s remarks about Carey, said with a smile, were limited to: “He’s a pistol.” Only Red didn’t say it quite that way.

Perhaps the most jarring headline Auerbach ever had to read over his morning chocolate milkshake—he drinks them like other people drink coffee—was the one last season that announced: CARD-PLAYING BUDDY FINES AUERBACH. Sounds terrible, doesn’t it? The story itself was another thing. Auerbach, who now makes his home in Washington, D.C., was given a technical foul that called for an automatic fine. The foul was called by Arnold Heft, a referee who lives in Washington, too. A newspaper called Podoloff after the game and said, “How about Heft throwing Auerbach out?”

“Yes,” Podoloff answered, “and they’re old Washington buddies, too. Probably play cards together back home.”

“Heft and I aren’t even friends socially in Washington,” Auerbach said in explanation. “We travel in different crowds. And I’m not a card-playing pal of anybody in the league. I called the paper that ran the headline and asked for a retraction. It was the first time I ever complained to a paper about a story, even though there have been plenty I didn’t like. I got the retraction, for all the good it did.”

Only one Boston paper, the Record, appears to be on Red’s side, and surprisingly enough it’s famous hatchetman, Dave Egan, is Auerbach’s strongest supporter. Egon once wrote: “They do not want Auerbach in the league, despite the fact he guarantees the integrity of the sport. He stands outspokenly for his men. He fights for them, as he goes around the country playing wide-open, spectator-appealing, aggressive basketball. Yet he is penalized again and again both by hammy officials and by the president of the league, penalized because he battles against insipid homing pigeons who in close games guarantee that the Celts will not win a game away from home.”

Auerbach says about Egan: “If you’re checking what the Boston writers have to say about me, be sure you don’t miss my boy. I’d be dead without him.”

What the Boston press has against Auerbach is a good question. Numerous private theories exist to explain Red’s bad local press. It’s his temper, or his outspoken opinions, his alleged win-at-all-costs approach to the game. The two best guesses are (1) in five years Red never gave Boston a winner, and/or (2) they can’t forget or forgive that he passed up Cousy, New England’s greatest basketball hero, in the college draft.

As provincial as the next town, Boston likes winning teams, and although the Celtics have been close many times, they’ve never taken the big prize. Some critics say it is Auerbach’s fault. The way the argument goes, Walter Brown has spent more money than any owner to get a good club. He pays top salaries, has his team travel first class, and he gives Auerbach a free hand in draft selections and trades. The club is obviously good, this theory continues. Its high-scoring records prove that. The Celtics are, in fact, the highest-scoring team in the history of the game. They are also the most scored-against. This is widely blamed on Auerbach. It is a coach’s job, the critics say, to develop a sound defense.

The rebuttal to the argument is that since Auerbach has had the team—he is in his sixth year—Boston has not had a big man to clear the boards. “I’ve always been looking for that good big fellow to get me the ball. I don’t need shooters,” he says. “Never did. But where can you get that big man? We always finish close enough to the top not to get a good early draft choice. There isn’t much we can get from our territorial rights. Besides Holy Cross, we don’t have a real big-time college team in our territory.

“That lack of a big man has been our defensive problem, too. We play good defense. We don’t coast, like some papers say. We work hard. But we lose it off the boards. Macauley can shoot, but he can’t get us the ball. He isn’t sturdy enough. This isn’t like baseball or football. With our balance, one man could make the difference. Give me Harry Gallatin, and I’ve got a good ballclub. But I can’t get a player like that. Nobody will trade one of their first seven men. This is my toughest season since I’ve been at Boston. We lost Fred Scolari (retired), Frank Ramsey (service), Bob Brannum and Don Barksdale (retired). It isn’t easy to give rookies a chance to develop, not when you only carry 10 men. With a tough, 72-game schedule, you’ve got to play all your men. No one can afford the luxury of a benchwarmer.”

For a while, Auerbach thought Chuck Cooper, the Duquesne All-America, was going to be the answer to his rebounding problem. But, according to league scuttlebutt, Cooper didn’t hustle enough to suit Auerbach. Chet Noe and Ed Mikan, both 6-foot-8, had a crack at the assignment several years ago, but neither was an accomplished rebounder. At 6-foot-6, Don Barksdale was a good boardman, but he worked best out of the corner. The Celts got Bob Houbregs and Ed Miller when Baltimore folded early last season, but Houbregs lost the No. 10 spot to Togo Palazzi, and Miller never came out.

The closest the Celtics have been to solving the problem was when Gene Conley, the Milwaukee Braves pitcher, was with them. “He definitely would have been the answer,” Auerbach says. “With a season of experience, he would have been an excellent rebounder.”

The story of Cousy and the draft is an outcropping of New England provincialism. Understandably, the Celtics and their fans always want the top players from the area to be on the pro club. When George Kaftan, who was rated above Cousy when they were college teammates, and Tony Lavelli of Yale showed they weren’t going to make it in the pro game, the fans were disappointed. The next year, when Cousy was eligible for the NBA, the fans and press wanted another chance for a local hero to make the grade. Cousy, they felt sure, would be great with the Celtics and would rebuild New England’s basketball reputation.

“They were right, but for the wrong reasons,” Auerbach says. “I passed up Bob in the draft because I needed a big man, and you can never be sure of backcourtmen in this league. Charlie Share (6-foot-11) was available. I figured I could take a big Share and, if I wanted to, trade him for Cousy and another player. I was wrong.”

Red was not upset when he conceded he had been wrong about Cousy. “We got him anyway (drawing his name from a hat when Chicago and Tri-Cities folded and Bob, Max Zaslofsky, and Andy Phillip became available). Bob made it because he worked hard, and he was smart. People just don’t seem to realize how much he has improved. Especially on defense. He made the two greatest defensive plays I saw all last season. He listens to what I tell him, he gives all he’s got, and he learns every day. All that talk about prima donnas on this club is silly. Some clubs need two balls in the game. But our three big scorers have a good argument in their favor. No matter how many points he scores, Cousy still leads the league in assists. Mac does well in that department, too. And Sharman is a remarkable, dedicated athlete.”

Once worked out, the Cousy draft issue confirmed at least one plus aspect of Auerbach’s reputation. This is Red’s claim as a trader. When he was first with Washington, he bought and sold with the flair of a Branch Rickey and produced the top club in the league for three seasons. When he quit the Caps—like Charlie Dressen, he wanted more than a one-year contract—he joined a weak Tri-Cities club and horse-traded it into a respectable quintet.

“Probably his best talent-grabbing coup was when he plucked Frank Ramsey, Cliff Hagan, and Lou Tsiropolous, the Kentucky stars, from the draft in a single neat maneuver. In April 1953, the owners at the draft meeting passed a rule, to accommodate Ed Gottlieb, permitting the drafting of a player once his class graduated, regardless of his personal status. When it came his turn in the first round, Auerbach named Ramsey. On the third round, he tagged Hagan. A few eyebrows were raised. Both were due to stay in college a fifth year, after Kentucky had been barred from competition in 1952-53. On the eighth round, Red picked Tsiropolous.

Suddenly, Ned Irish, boss of the Knicks, flared: “They can’t be legally drafted. They’re still in school.” Irish was wrong. It was legal. The class had graduated.

The NBA owners, never ones to let precident or prestige stand in the way of expediency, passed an amendment to the rule that had been established an hour or so earlier. But Auerbach had his men, and although Hagan and Tsiropolous will not be available until next season, their excellent showing in service ball has convinced many in the NBA that they will help the Celtics.

Where Auerbach acquired the little skills that helped him maintain both his job and reputation in the NBA is difficult to determine. At Eastern District High School in Brooklyn and at George Washington University, he was an average ballplayer, whose modest scoring went under the heading of “clever little floorman.” At both schools, Red says, he acquired a solid understanding of the game. But, he explains, “I learned most of my tricks in the playgrounds of Brooklyn.”

Still, he lacked both coaching experience and the big name as a player when he landed his coaching job with the Caps. He had had only brief prep school coaching when he went into the wartime Navy and joined Gene Tunney’s physical fitness program. Just after his service discharge, Red walked into the office of Mike Uline, owner of the Uline Arena in Washington, and sold him a bill of goods. The entire deal is typical of Auerbach’s daring approach and salesmanship. After his discharge, he had lined up an impressive collection of top basketball talent—Bob Feerick, Fred Scolari, Johnny Norlander, Irv Torgoff, and John Mahnken. Give me the job as coach, Red told Uline, and I guarantee you a winner in this new league being formed. Not only was Auerbach’s selling job effective, his guarantee was accurate. In the next three years, the Washington Caps won two division titles.

It was a good start, Red himself concedes, and “I’m not sorry for getting into this business, but it isn’t an easy racket.” Although he spends almost eight months at his job, his wife and two daughters live in Washington the year round. “I’m on the road so much that it wouldn’t make any difference if they moved to Boston for the season. I get to see them just as often there as I do here . . . which isn’t very much.”

The pace of a 72-game schedule requires Auerbach and his players to hop around the league’s eight cities four or five times a week. Often, when the Celtics have a night off, Red has to take a trip to scout another club or check on a college prospect. He watches basketball almost every night in the week, talks about it almost every waking hour.

“Coaching is a lonely life,” he said more than once. “When we’re on the road, I’m traveling secretary and business manager. I have to check our transportation, hotel accommodations, count receipts. When I’m in Boston, I have to be careful who I associate with. I’m always making sure to avoid gamblers or flashy characters. I don’t go into restaurants that have a reputation for serving the gambling crowd. And a coach can have many friends. With your players, you have to be boss. I have to know their problems and help them out when I can. But I can’t have any of them as social friends. Who else is there?”

Red has a crew of second-guessing fans—”my assistant coaches,” he calls them—who take up some of his time. They take short trips with the team, wait for Red in the lobby of his hotel, ask him dozens of questions about the team and the opposition, and usual pro ball gossip. They give him free advice, too.

Red lives at the Lenox Hotel in Boston. He has a modest two-room suite. The chambermaid keeps tabs on his laundry, he does a dismal job of packing his bags, and he eats his meals at an assortment of beaneries. “A game tires me out,” he says. “I eat lunch and then nothing else until after the game. If I ate before the game, I’d feel contented. You can’t. You’ve got to stay sharp and hungry in this business.”

And Auerbach is as sharp and hungry as any tiger. As wily, too. With or without ethical defense, he is tricky, in his game strategy as well as elsewhere. It is probably to his credit as a coach that he is willing to try things. He was the first in the league to use a high post—for passing from the center for set-up plays. He uses a fullcourt press freely; he once used it for an entire game against the Warriors. Such practice is now hampered by the two-shot backcourt foul.

One trick which Red does not admit to using, but which he acknowledges as an existing practice around the league, is the fast clock (or its twin, the slow clock). A simple tactic, it requires only that the timekeeper, a member of the firm, ring the buzzer before time has run out, or after, as the situation dictates. Convinced that the ruse is employed, Red makes a habit of yelling out the seconds at the end of a quarter, if his team has possession.

“Once we had the ball with 10 seconds left in the game. We were behind by a point and had decided who would take the last shot, and when I started counting with the clock . . . ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five. Just as I yell four, the buzzer sounds. Sure, I exploded, but it didn’t do me any good. Not that time.”