[Another article about Mr. Wilt. This one is peppier than most and definitely worth the read. It was the lead story in the Sports Review’s 1967-68 Basketball annual, and a journalist named Leander Jones had the honors. I’m not familiar with the name. Toward the end of the article, Jones muddles Wilt’s declared free agency a little bit, and the rumors of Chamberlain, Baylor, and Alcindor jumping to the ABA made good copy. But they had no basis in fact. Otherwise, Jones offers an informed overview of Wilt, circa 1968.]

****

To fully understand the transformation of Wilt Chamberlain, one must first understand the enigma of being over 7 feet tall and a pro basketball player . . . and if you are going to be one you might just as well be the other.

Both facets of Wilt’s life were driven home on a snow-flecked December night in 1965. The Newark (NJ) Air Terminal was jammed with holiday travelers, despite the lateness of the hour. Christmas music wafted through this spacious building, as arriving travelers hurried to waiting arms and departing travelers scurried to the same comfort hundreds of miles away.

Five men came through the main doorway carrying zipper equipment bags bearing the 76ers insignia. For the most part, they went unnoticed by the hustling crowd. They were followed by three more men with the same suitcase. As the group shuffled in zombie-like silence towards the East arcade . . . they caused only an occasional glance from passersby.

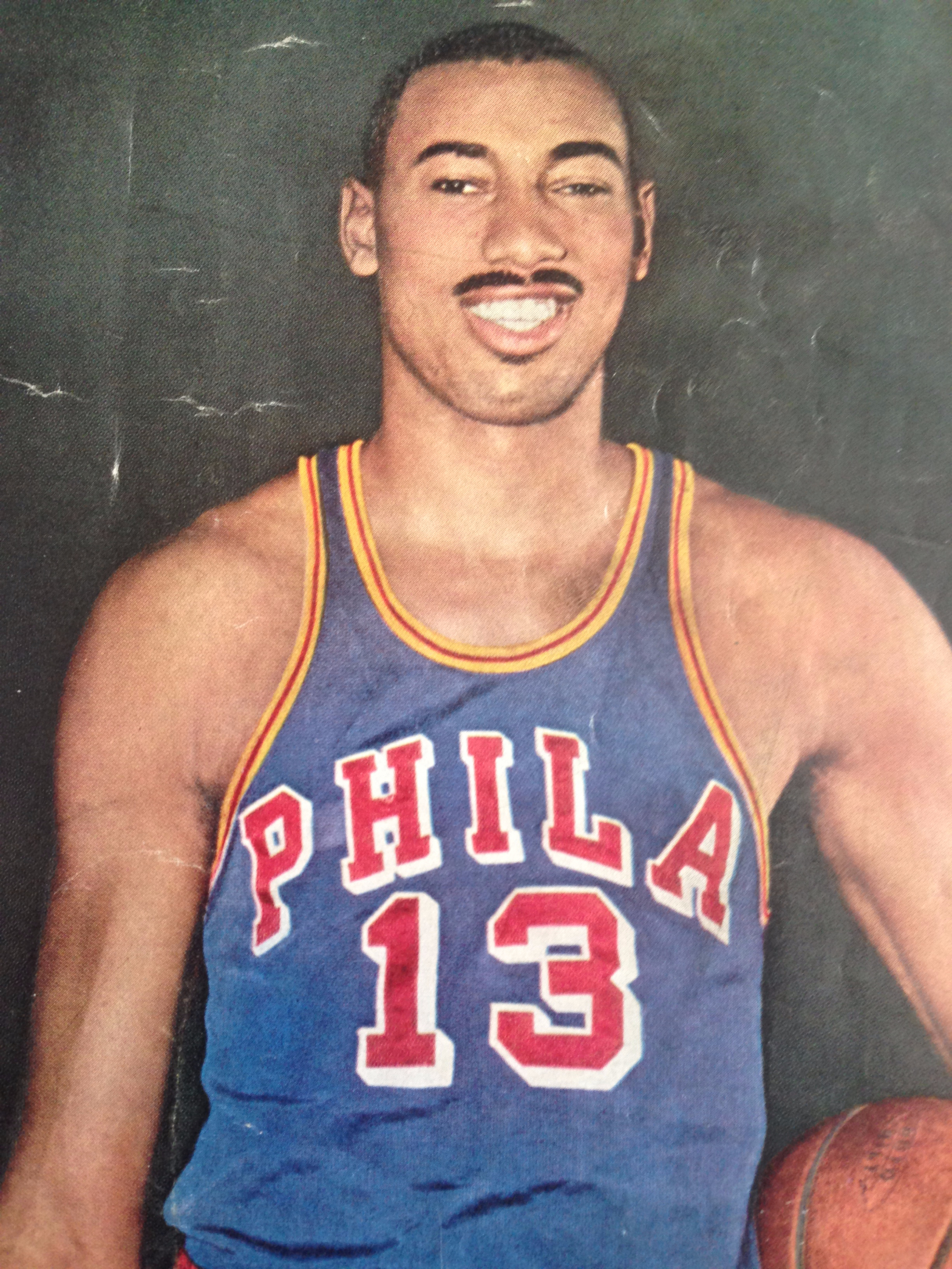

Then, as if a trumpet blast had sounded, the doors parted and in strode goateed Wilt Chamberlain, all 7-foot-1 and 1/16 inch of him. The crowd stopped just as if someone had suddenly pressed a button on a stop-action camera. They froze, and they stared . . . gawked would be a better word, as Chamberlain moved in long striding steps towards the East arcade.

Then the moment which Wilt (and his fellow members of the altitudinous set) hate happened. A middle-aged man who had certainly enjoyed both of his aerial cocktails enroute began with an absolute original, “. . . hey, boy, how’s the weather up there?”

Encouraged by the near-drunk boldness, others began the comments. “Duck, Wilt, there’s a plane landing,” and one woman shoved a cringing youngster to Wilt’s side and said, “Mr. Chambers, let me take a picture of my son with you. His friends will never believe he saw a real giant.”

This is the cross carried by the tall pro basketball star, and sometimes it is questionable if what he is paid justifies the mental anguish.

Almost from the time he entered Philadelphia’s Overbrook High School, Wilt began wondering if it was worth it all. He never enjoyed any of the protection which was meted out to Lew Alcindor, another of the nose-bleed set, when Alcindor attended Power Memorial High School in New York. Nor was Wilt given any of the cloistered protection when he attended Kansas that Alcindor receives at UCLA. Wilt was box-office, and anybody who thinks college basketball doesn’t cater to box-office better believe that Joe Namath is joining the priesthood.

When Wilt left Kansas to play with the Globetrotters, it was just a little bit different. They were showbiz, and they moved in showbiz circles. Surrounded by eccentric characters who thrived on public adulation, Wilt was divested of some of the stares by those who tried to attract attention.

Back in the pros, he became box-office once again, and when he averaged 50.4 points per game under the guidance of Frank McGuire in 1961-62, he was doing what he was asked to do . . . score . . score . . . score. He hooked, he jumped, he tapped, and he dunked; and that was the Philadelphia Warriors offense . . . Wilt Chamberlain. He did little else other than grab the ball off the backboard and rush downcourt to set up. All four men worked to get the ball into Wilt. Wilt worked to get the ball into the basket, and he did that an average of 20 times in each game.

When the Warriors went West, Wilt was intended to be the attraction that would sell pro basketball on the West Coast. Three-thousand miles away from the tiny knot of friends he had on the East Coast, Wilt became disillusioned with the Western migration. He busied himself by making wise investments in real estate, but his basketball efforts were only so-so. He was not as popular in California, as it was thought he would be, and the fans took to booing and ridiculing his efforts. An extremely sensitive individual, this worked inwardly on Wilt . . . and eventually it showed outwardly. His scoring average dropped from 44.8 in 1962-63, to 36.8 in 1963-64, and finally to 34.7 in in 1964-65.

Not bad, but not good enough for the Californians.

When the Syracuse franchise was transferred to Philadelphia, Wilt went along with the deal. He resented being pushed around like a head of cattle and was on the surface not too happy about returning. For a while, it was touch-and-go as to whether he would join the Philadelphia 76ers.

In the turbulent existence that is Wilt Chamberlain’s life, his actions have frequently been influenced by others; but only a very few have found the key for solving Wilt’s complex nature. One such person was Frank McGuire, but Frank’s personal problems forced him to take the South Carolina coaching job rather than head West with the Warriors in 1962. Another such influence on Wilt was Alex Hannum, who had been named coach of the 76ers, replacing the mild-mannered Dolph Schayes.

Schayes had taken the 76ers to first place in the East, but failed miserably in the playoffs. Being a good businessman, Wilt had joined the 76ers, but was at constant cross purposes with Schayes almost from the start.

Under Schayes, the top six men on the 76ers were Wilt, Hal Greer, Larry Costello, Dave Gambee, Chet Walker, and Lucious Jackson. Their ragged play in 1964-65 left them third in the East, as the top six men fouled out a total of 30 times, and the 76ers ranked even behind the Knickerbockers, one of pro basketball’s weakest teams, with 53 team disqualifications.

With Wilt about to quit and the 76ers about to crumble, Hannum came on to replace Schayes and rescue both Wilt and the 76ers. In his first season with the 76ers, Hannum re-created Wilt’s style and, and so doing, gave Wilt what he wanted most—a championship!

In 1965-66, the 76ers edged into first place and cut down their disqualifications to 39. The unit that brought this change about was Chamberlain, Greer, Walker and Jackson, with Wally Jones and Billy Cunningham replacing Costello and Gambee. Although the pieces were beginning to shape up, they were not yet ready, and the Celtics edged the 76ers in the playoffs, 4-1.

This should have been a portent of things to come, however, for almost from the outset of the 1966-67 season, the 76ers had that title touch. Hannum had prepared Chamberlain for a new mission, and from the outset, it was obvious that Wilt was working with a changed philosophy. Accuracy and teamplay replaced his previous do-it-all for box-office flamboyance. Where he had 250 assists in 1964-65, he passed off for 414 buckets in 1965-66 and upped it to 630 in 1966-67.

His rebounding had always been a strong point for any team he played with, yet the “new” Wilt managed to pull down 1,957 in the 1966-67 season as compared to 1,943 in 1965-66 and only 1,673 the year prior, the latter being his worst rebounding season in the NBA.

Thus, the transformation had begun . . . but it could conceivably come to a screeching end! Someplace along the line, SOMEONE has jerked the rug out from under the new Wilt Chamberlain—and big Wilt doesn’t rumble softly.

The “team play” bit cost Wilt the first scoring title in his eight pro seasons, but it brought him his first team championship since he was in junior high school. Nearly 15 years of famine before winning a championship and many, many years of frustration.

Each of those disappointing seasons came with the same format: Wilt sweeps the backboard. Wilt passes off and goes down to set up. The ball comes into Wilt. And Wilt scores . . . or nobody does . . . If the shot is missed, Wilt gets the rebound.

The price that Wilt paid in physical torment under this frustrating formula was awesome . Up tight, where those screens can blot out the murderous jab of elbows and knees from the officials’ vision, it is called the “slaughterhouse,” and for seven years, this is where Chamberlain labored. He put in over 425 hours of almost continuous play in the “slaughterhouse” and NEVER FOULED OUT OF A SINGLE GAME IN HIS ENTIRE PRO CAREER.

When Hannum took over in 1966, there was a new plan for Wilt. He came out of the “slaughterhouse” much of the time and became the hub of the 76ers’ offense. Greer, Jones, Cunningham, Walker, and Jackson buzzed around the big post man like a swarm of stinging bees. In-and-out, and when a defensive man took his eye off them for a split second, up they’d go with a lightning jumper.

The wisdom of using Wilt as the deep hub of the 76er offense is pointed up by the fact that only three others (Greer, Walker, and Cunningham) managed double digits the year before Hannum took over, and they represented an average of 52 of the 76ers’ 117 joint output . . . less than half.

Last season, the same trio were joined by Jones and Jackson to score nearly two-thirds of the 76ers’ 125-point average. Wilt had turned the scoring over to the boys in the backroom and had become the team’s traffic cop as he palmed off a record 630 assists . . . half again more than the best center in the NBA had ever tallied, and that happened to be 414 by a fellow named Wilt Chamberlain.

It is ironic that Chamberlain’s transition to a team player should bring him his first championship . . . and contractual problems to boot. Here once again is the complexity of Wilt in its most-confusing form.

When he left San Francisco, Wilt joined the 76ers begrudgingly under Schayes. The third-place finish that first year together opened a schism between the two, which erupted completely when they won the battle, but not the war, in 1965-66. The breach was closed by the signing of Hannum as coach, and Alex, a ballplayer’s coach, spun his own charm over the unhappy Chamberlain. The format for last season was placed on the drawing board for Wilt and, at just the right moment, they talked contract.

In the mixed-up world that is the NBA, there is a rule against a player having a piece of the club . . . at least openly. The deal the 76er brass laid before Wilt included lots of goodies besides plain old taxable money. First off, it was for one year with a muttered gentleman’s agreement (not in writing) about “only being for a year.” Wilt has now interpreted this to mean that his contract was NOT subject to the usual option clause which binds NBA players into almost continual servitude . . . or at least it did until Rick Barry challenged its validity.

Another inducement Wilt says that he was to get was a piece of the club, something which could not be put in writing as such. After his magnificent teamplay of 1966-67 brought the 76ers their title, Wilt lined up to discuss those hidden persuaders he had accepted, but the 76ers brass didn’t want to know from nothing.

Their hear-no-evil, speak-no-evil, see-no-evil attitude began when Wilt’s name had been linked by a New York columnist as a possible player/owner in the new ABA. One report had the deal all buttoned up with Wilt to be a player owner in 1967-68, to be followed by Elgin Baylor (who would play out his option in the NBA and join Wilt at the conclusion), and then the duo would be joined in 1970 by Lew Alcindor, who would be ready for the pros that season.

By the time Alcindor took over, Wilt would have become the first Black owner in professional sports, with Baylor wrapping up his 10 years of pro servitude and joining Wilt as a one-third partner, the other third belonging to Alcindor. This would be possible in the ABA, where there is no restriction against a player being an owner of the club.

It works in reverse, too, and if things get bad enough in Oakland, Pat Boone may go into the Oaks’ backcourt, white buck shoes and all.

Chamberlain is a proud individual. Down deep, he didn’t enjoy losing the scoring crown he owned since his very first season in the NBA. Fans who pay their way to see Chamberlain perform expect him to score a basket every time he has possession of the ball.

The new Wilt Chamberlain scored fewer points last season, and it resulted in bringing Philadelphia its first championship. Still, the zest for individual brilliance remains inside Wilt. Last year, he sacrificed the scoring title for a team victory. Everyone talked about it, and it seemed that everything Chamberlain had done in the past was wrong.

What Wilt Chamberlain would really enjoy is the personal title to go along with the team championship. Only then will he accomplish everything he desires out of basketball.