[This is a long feature article mainly about St. Louis Hawks’ owner Ben Kerner. So, I’ll keep my comments brief. Kerner, though mostly forgotten today, was one of the NBA’s true pioneers and a man with a plan. Make that, lots of plans. And boundless energy. Wrote Leonard Koppett in the book 24 Second to Shoot: “Kerner was flamboyant, noisy, liable to lose his temper, restless, and at times crude—but he had the capacity to recognize and admit mistakes, to analyze problems, find imaginative solutions, and grasp the true role of publicity in promotions.”

Wrote Bob Pettit in his autobiography: “I think the NBA is lucky to have Mr. Kerner as an owner. He is a very progressive-thinking person, a promotion-minded owner who is always looking for ideas to help sell his product and further the cause of professional basketball.”

Back to Koppett writing of the mid-1950s NBA: “What Kerner came to stand for, within the league, was ‘big-league Image” as a goal. [New York’s Ned] Irish had always fought for this, but lost; [Boston’s Walter] Brown had always been eager to go along with it; [Philadelphia’s Eddie] Gottlieb had felt it was overrated; [Fort Wayne Fred] Zollner always considered his team a very private proposition. The others had always been too busy fighting for survival and fighting each other to worry about such long-range refinements. Now Kerner saw the importance of it and helped shift the balance of power within the league towards this outlook.”

Make no mistake about it, Kerner was an acquired taste. I once met Marty Blake, who had been Kerner’s number two man in St. Louis, and our conversation turned to his former boss. Blake’s tone after so many years was telling. It was like listening to the survivor of an epic hurricane tell his tale. There was awe, respect, and some thrill that eventually dead-ended into a weary ache. It sounded like Blake was glad he experienced it, but he never wanted to live through that one-man human hurricane again.

But I digress, let’s let journalist Irv Goodman explain more about Hurricane Ben. Goodman’s story ran in the December 1958 issue of SPORT Magazine.]

That the volatile-and-proud St. Louis Hawks, champions of professional basketball, are still owned by the volatile-and-proud Ben Kerner, the man with the shoestring budget, is amazing. The way things usually work out, this fellow who tried to survive in the jungle of pro ball while possessing only a talent for corner-cutting, a desire to own a winner, and a nervous stomach—well, he should have fallen flat on his face. He stumbled—oh, how he stumbled—but, stubbornly, he kept squirming and scrounging and straightening out until, finally, he hit the jackpot.

This is the essence of the success story of the remarkably happy Hawks and their exuberantly happy boss. There is much more to it, of course, since both the team and the man are complex commodities, products of the war waged by pro basketball to achieve the status of a major league. But remember, as we trample through their life and times, that Ben Kerner and the young men who have played for him fought the instinctive fight of the survival of the fittest. If they have come out of it with some lumps on their head, that’s okay, too. They made it, and it wasn’t easy.

Like any good winning fighter, the Hawks and their boss ignore the wounds and dip deeply into the joys of success. No other NBA club has as happy a time. With Ben Kerner and his boys, this comes easily. Both the team and the man are given to frequent bursts of physical and emotional activity. The team is exciting; its owner is excitable. Both have seen and have been the worst and the best that there is in pro ball. Both are, at the moment, feasting at the bountiful table of the victor. They like it fine.

When you say Ben Kerner owns the Hawks, you give that word its full due. He is the Hawks, and he is nothing else. He rides his team’s back to victory, and they ride his back to the rewards. It is a full ride.

Kerner lives and dies with his team. A loss cuts deeper and lasts longer with him than with others. He wakes up at night in a sweat, remembering the call that cost him a ballgame, and he dresses, goes out into the street, and drives hard through the dark, quiet avenues of St. Louis. He is a familiar sight to the nighthawks of the city, the cops, the milkmen, the lovers. An all-consuming competitor, he will return home at four in the morning, gulp large glasses of orange juice, and assault his bed again.

He once sent a St. Louis newspaperman fleeing through the streets when, driving downtown with him one day, he stopped at a corner newsstand for a late-addition newspaper and proceeded to read it as he negotiated his car through traffic. The sportswriter ordered the car stopped, stepped out gingerly, and with a resounding, “I’ve had it, Benny,” was gone.

Kerner had a fight with Red Auerbach, once a coach of his and now the fearless leader of the Boston Celtics, over the strange charge that someone had tampered with the height of the baskets for a championship game between their two teams. It was a one-punch contest, Auerbach delivering the blow cleanly to Kerner’s nose. “I took his best punch,” Kerner said afterward.

He has had other fights, including one with referee Jim Duffy, in which he took a swing at the official following a backcourt-violation call. This was in a game in a season when his team was in last place and going nowhere. “That didn’t matter,” Kerner says even now. “He took something from us.” The league took $500 from Kerner.

He once threw two chairs at an official over one call and was assessed two technical fouls for it. When charging was called on Ed Macauley with 17 seconds to go in the second overtime of the final playoff game against the Celtics two years ago, Kerner came apart at his well-worn seams. The call had cost the Hawks the game, and thin, mild Macauley is notorious as a non-charger. These facts clanged in Kerner’s brain. For months afterward, he woke up at night, as from a nightmare, screaming at the officials. “To this day,” he says, “I think about it, and I get sick.”

He fired—or at least he did not rehire—the coach of his championship team, Alex Hannum, who has an equally incendiary temperament. And he has gone through more coaches than any other owner in the National Basketball Association.

So? So, Ben Kerner is nervous and excited and aggressive and troublesome and tough on officials and coaches? Well, if he is—and none of this should be put away as unchallenged fact—remember, too, that he is a dedicated, friendly, generous, honest man, of whom his greatest star Bob Pettit has said: “If Ben traded me, I quit. I only want to play for him.” Such praise is not given to many men who sign the checks.

But Kerner—in the 11 years when his teams were bad and he lost money, and in the two years when his teams were good and he made money—has always wanted to spread the wealth. He just never had it until lately. One of the more-entertaining news stories of the past year was the flood of gifts he plumped on his players. It just happened one night last November when Pettit showed up in a hotel lobby wearing a new sports jacket that was noisily admired by his teammates.

“I’ll tell you what,” Kerner offered. “Win five in a row, and I’ll buy you all sports jackets.” So, the Hawks, not doing well at the time, went out and won five in a row. “Let’s keep it going!” Kerner shouted, disinclined to break the winning pattern he had suddenly designed. “Win tomorrow night, and I buy sports shirts!” Again, the Hawks won.

Now new ground rules were set up. After five wins in a row, only road games—the tough kind—would count. “Win the next [road game], and I buy slacks,” he said. The Hawks lost, and the slacks were out.

“We got to start over,” Kerner said. “I’m sticking with the system. Win five again, and it’s shoes.” The team won five, and the 12 men on the roster at the time went out and got their shoes.

“Okay now,” Kerner said. “Back to the slacks. Win one on the road.” The Hawks won, were the best-dressed team on the circuit, and now led the NBA by eight and a half games.

Kerner wouldn’t and couldn’t quit, and, everyone knew, shouldn’t quit. The league and the other owners didn’t like what he was doing, but that didn’t matter. “Okay,” he announced. “For one win, sweaters.” So, the Hawks went into Syracuse, a tough away-town, and set a new league scoring record, piling up 146 points.

By now, Kerner thought that the players’ wives might be feeling slighted, so he offered hats and handbags for them if the streak were extended. But it wasn’t, and he didn’t pick it up again. “I’ll go broke,” he gurgled unconvincingly. He had spent almost $150 per man on the clothing, but that wasn’t the reason.

League commissioner Maurice Podoloff had finally stepped in and stopped the giveaway as an illegal incentive procedure. “I was waiting for the letter,” Ben reported. “Sure, I wanted to win five again, and I’d have been willing to be fined for it. But the owners were complaining, and they were right. If I had been them, I’d have been screaming my head off long before that.”

It was hindsight that suggested to Kerner that his clothing giveaway would turn out to be good business—and he is a very good businessman—but his first instinct, at the moment he came up with the idea, was a desire to be generous.

He is notoriously generous. When the All-Star game was held in St. Louis last season, Ben was host at the St. Louis baseball writers’ golden anniversary dinner to 20 players on the two teams, all the coaches and officials, as well as members of his club, their wives, and his office force. Originally, he ordered 100 tickets, at $10 each. When additional requests came in, he ordered 40 more tickets.

To the fans in St. Louis, he is an honest promoter. For a Saturday night game against the Boston Celtics, for example, he booked Count Basie and his band to entertain the crowd. You’re crazy, people told Kerner. A game like that is sold out anyway. Why don’t you book Basie for a Wednesday night game against Minneapolis?

“Because.” Ben told them, “I’m in the business of merchandising a product. People must have confidence in me, and I can’t expect them to be doing me any favors. If they’re good customers, I have to show them I appreciate it. I give them an extra when they don’t expect it, when they know it’s an ‘extra.’ I don’t go around pleading any Fifth Amendment.”

It has been good business. After losing money in each of his first 10 years in pro ball, Kerner broke even (“I even made a few dollars,” he says) his first year in St. Louis and has made good money the past two seasons. Last year, in 38 home dates, he drew 276,000 customers, third highest in the league behind New York, with an 18,000-capacity hall, and Boston with 14,000. Kiel Stadium, the Hawks’ homecourt, holds 10,000.

“I can’t expect to top those two clubs in attendance with a smaller place, but I’m not complaining, believe me. It’s some difference now from what it used to be. What did I draw in the old days? Well, you can say that in my first year, I did under 50,000 for the season, well under it. And how!”

Kerner’s impulse for generosity shows best with his players. After the Hawks won the championship this past April—in a titanic final game, the exciting conclusion of which Kerner missed, after 13 years of struggling and waiting, because in those last 30 seconds he blacked out—nothing could contain the happy boss. In his time, this man has been called a chiseler and a shoestring operator and a small-timer, and now, having survived this and holding claim to the champion, he wanted to dignify his status. The league gives no memento to its winner, the way baseball and football and even the Little League does. Wanting to correct this, Ben went out and had special rings made up, with diamonds inset, at a cost of almost $300 per ring. They were larger and shinier than baseball’s World Series rings, as Ben had wanted them to be. He gave out 26 rings to the team, the writers who traveled with them, the radio broadcasters, the fellows on his office staff, the trainer, the clubhouse boy, his attorney, the club physician, and himself.

In the gentle arms of victory, however, as it was under the heel of defeat, Kerner lacks whatever talent is required for unfeathered relaxation. His problem is that he cannot turn his back on his basketball team, he can never forget about them or ignore them. (The fact that he is a 40-year-old bachelor adds to the problem because it allows him that much more free time to worry and fret and not eat.)

He proclaims proudly that he has never taken a vacation, and if he did, he would become anxious, worrying what was happening back at the shop. He would have a miserable time. In his closeness to his franchise, he reminds you of your hard-working father (or was it your uncle?) who loved his business while he cursed it, who bemoaned the long hours and working conditions and the fierce competition and the tiny profit margin, but who was lost without it. There is something refreshing, in these days of boards of directors and 100-man trusteeships and absentee ownership of so much of the property in sport, to find a man who owns all of it, watches all of it, and frets in his mother-hen way about every little part of it.

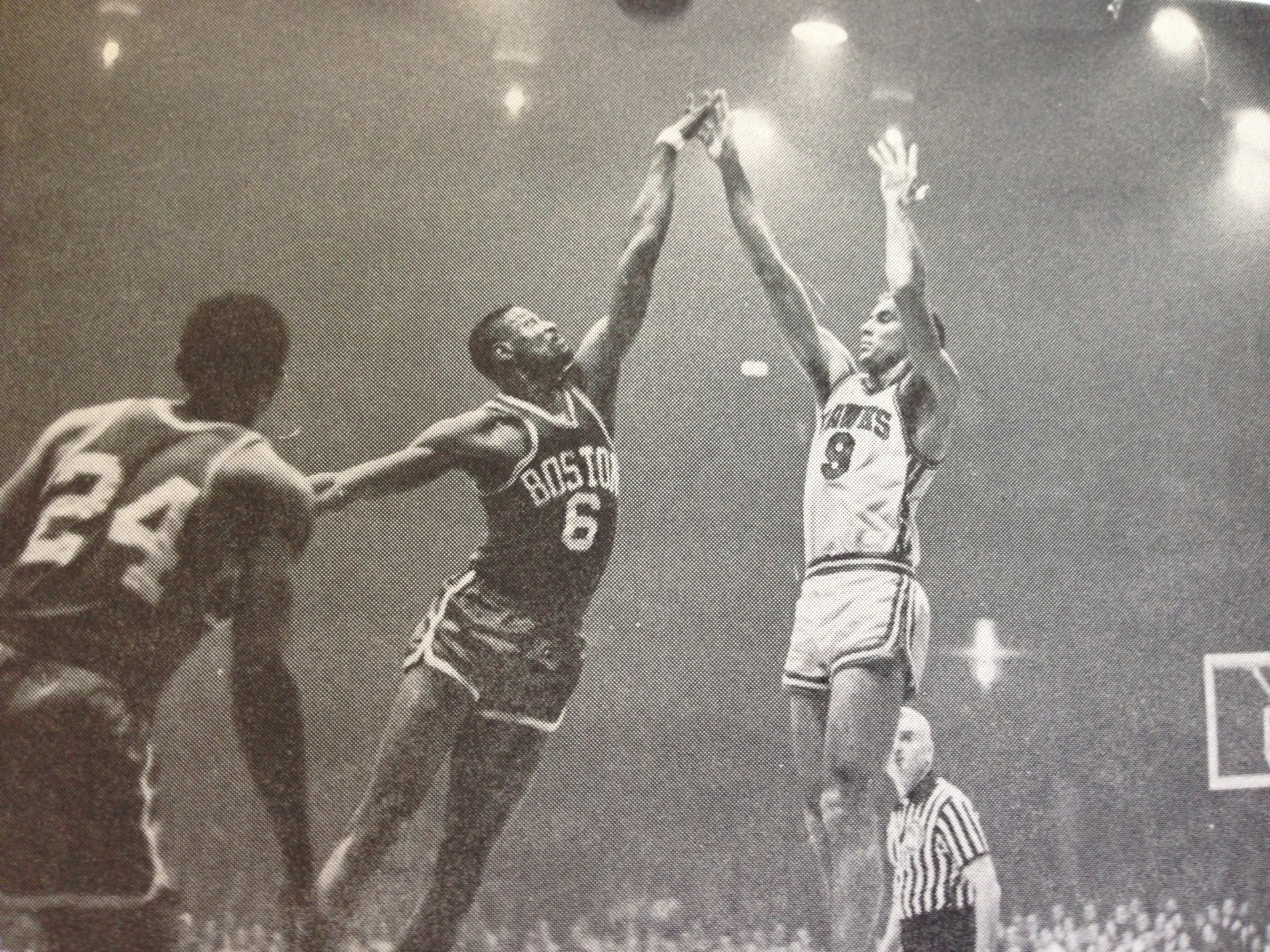

With such pride of ownership, you take nothing for granted. Not anything. In the opening second of the first game of the 72-game NBA schedule last year against the Celtics, the Hawks lost the center tap. Kerner flung his cigarette to the floor and muttered, “We’re in trouble.” Such are the sentiments of a man possessed.

He once took Buddy Blattner—the former baseball player who now does the radio broadcasts of Hawk games and is a close friend of Kerner’s—and his wife to a St. Louis nightclub. A girl vocalist who delivered her spicy lyrics while wandering from table to table was on, and the room was dimmed, with only a spotlight following her. When, in her wanderings, she arrived at Kerner’s table, the spotlight fell on Ben, who had his head lowered to table level and, with the aid of a pocket flashlight was reading a newspaper. In it, there was an item about the Hawks.

The inroads of such dedication are considerable. Ben sat once with Bill Rigney, the manager of the San Francisco Giants, at a sport luncheon at which ravioli drowned in hot sauce was served. Kerner looked at Rigney, and Rigney looked back. “Don’t you wish,” said nervous-stomach Ben to nervous-stomach Bill, “we could eat this stuff?”

Kerner comes to a basketball game looking, fittingly, likes the best-dressed man in the hall. He leaves looking more like Emmett Kelly, the clown he has often booked as a halftime entertainer. His tie gets undone early, then his tie pin drops to the floor, and his clothes begin to look slept in. And he invokes his fair-sized collection of superstitions. When the game is over, you may make light of these habits, but at the moment of battle, he lets go of nothing. He believes in continuing any circumstance that prevailed during good stretches by the Hawks. If he is smoking and the Hawks are ahead, he will burn the cigarette down to his fingertips. If the team goes behind, he will kill the filthy weed.

He once took the young son of his lawyer to a game. The Hawks were leading when the youngster announced that he had to go to the bathroom. Kerner refused to permit him to leave, not while the Hawks were winning.

Ben has acquired something of a reputation as a boss who is as rough on his coaches as he is good to his players. Understandably, the label is based on his ample turnover of coaches. When you ask him how many he has run through in his 13 years in pro ball, he has to stop and count on his fingers.

He is a bit bothered by the reputation, although he covers up with a sense of humor on the subject. But each time he made a change, he believed he had no choice. When he was running low in places like Buffalo and Tri-Cities and Milwaukee, he sought to get people’s minds off the bad teams by unloading the coaches. It is an ancient and unconvincing maneuver, but a persistent one in all sports just the same.

“My theory is,” Kerner says, “that if there is no club, then no coach can win. But the point is that when you lose, the coach gets more depressed than the players. I can’t say there was that much wrong with the coaches I picked. Look how well they’ve done elsewhere.”

He had Red Auerbach for one season at Tri-Cities—that would be Moline and Rock Island in Illinois and Davenport in Iowa. After that season, Commissioner Podoloff called Ben and asked for a favor. Boston wanted Auerbach. The city, considered important to the league, was in trouble. The Celtics had taken a poll, and the fans’ choice was Auerbach. Would Kerner let him go? Sure, Ben said. And that’s how one who is not unhappy about it was sent away by the tough boss.

Another of his coaches was Doxie Moore, who left to become the league’s umpire-in-chief. Another was Fuzzy Levane, who never coached before Kerner took him on at Milwaukee. The poor ballclub depressed Levane, Kerner thought, and after a year and a half of it, Ben sent for “a new man with a new perspective.” Levane now coaches the New York Knickerbockers.

Red Holzman, another of his coaches, did what Ben considered a good job. The team began to move under him, after it had shifted to St. Louis. But, perhaps for no reason other than disturbing coincidence, Holzman was what Kerner calls “a streak coach.” His team would win a bunch, then lose a bunch. The Hawks finished higher than a Kerner club ever had before, second in the division, and made it to the finals of the league playoffs. But the streak habit worried Kerner, and after the season, he considered making a change. It was then that he made the first of his three tries to get Andy Phillip, the man who is running his championship team this year. But Fort Wayne, which had player Phillip at the time, refused to let him go.

The next season, 1956-57, there was another slump, and Kerner became too distraught not to do something about it when the club fell into last place. He went after Phillip again. Andy was with Boston now, and Celtic owner Walter Brown was willing to release him. But on the Sunday before Phillip was due to move over, three Boston players got hurt, and Andy, still a very able backcourtman, was needed in Boston.

Holzman had already been informed that he was being let out, and now suddenly the team was without a coach. Kerner went to Slater Martin, whom he had just acquired from the Knicks, and offered him the job. But Martin didn’t want it. He couldn’t be a player and a coach, he said, and he wanted to play.

But Kerner persisted, and Martin agreed to try it for a while. He did well, better than most people know. He changed the team’s style of play and turned it into a champion. The Hawks had employed a slowed-down, deliberate offense, but Martin, knowing what that youthful personnel could do, got them to run. Even though he had been, for so long a time during the great days of the Minneapolis Lakers, the quarterback of the most-deliberate offense in the league, Martin was always a runner. He believed in it, and he was convinced that the Hawks, with Pettit and Cliff Hagan and Ed Macauley and Jack McMahon and himself, would win if they would run.

****

He was right. The club won four out of five games before Slater went to Kerner and turned back the job. I can’t do it both ways, he told Ben, and I want to play. And the Hawks needed him playing. So, Alex Hannum, the soon-to-be-celebrated Alex Hannum, who was the ninth man on the squad, backed into the job. He continued Martin’s running game and became a winning coach. The Hawks won the division title that season and lost the championship to the Celtics in an eventful seven-game series. The next season, he took the team all the way.

But trouble stewed between Hannum and Kerner. A temperamental and often hard-headed fellow, Hannum resented interference. And Kerner, while not openly intruding on the coach’s handling of the game, insisted on maintaining control of his property.

There was no open conflict until after last season’s All-Star game. Hannum had been given a bonus and a raise after the 1956-57 season. He was a good cheerleader, an asset for any NBA coach, and, for a while, he was listening to his players. In fact, the Hawks became known as a team of nine coaches and Bob Pettit.

Then it changed. Hannum stopped listening. Slater Martin came into a team huddle during a timeout and made a suggestion. “I’ll do the thinking around here,” Hannum barked. After that, Martin never again said a word in the huddles.

And, of course, there was the Selvy affair. As a rookie during the team’s last year in Milwaukee, Frank was sensational. He and the other rookie on the club, Pettit, were the fifth and sixth high scorers in the league. Then Selvy went into service, and when he returned last year to a much-improved ballclub, he had lost something—his confidence, according to many people close to the situation. Hannum didn’t use him, and Kerner screamed.

“It’s true the kid wasn’t fighting for his job,” Kerner explains, “and he wasn’t in top condition. But all I ever wanted for him was an equal chance. After all, I know it was the team, and not Selvy, that won me the title the year before. But this is quite a boy, the kind of kid I want in pro ball. He’s good for the game and the league, not just for the Hawks. He’s a fine boy, quiet, pleasant, shy. He doesn’t drink or smoke or swear. The public would like him to make good. I wanted only a chance for him. After that it was up to him to want to make good.”

Hannum would not go along. Selvy doesn’t fit our style, he told Kerner, and finally Frank was sent to Minneapolis, on the condition that the Hawks successfully sign one of two Laker draft choices who had gone into AAU ball.

(It is an interesting postscript that the Hawks didn’t sign either of the draft choices, and Selvy was returned to them before this season. He called Kerner one day this past summer and said, “I think I’ll retire.” Kerner was shocked. He had just spent a year battling a coach because of him—and now this. Ben talked softly to him. “You can’t yell at this boy,” he explains—and Selvy hedged, saying his knee was bad, and then finally that he had taken a job with a sporting goods firm. While Ben was on the phone with him, a newspaperman came in with the press wire story announcing Selvy’s retirement. The kid had given the news to the press before he had notified Kerner. Ben felt as if he had been pummeled, but he kept talking, and he finally convinced Selvy to come to St. Louis for a physical examination. The examination showed nothing wrong with his leg, Selvy resigned his job and was back with the Hawks. It had been a battle.)

****

But back to Hannum, another battle. The day after the Hawks won the 1957-58 championship, stories appeared in the St. Louis newspapers quoting Hannum as saying that if he didn’t get what he wanted from Kerner, he would stick with his construction business in California. I want a two-year contract, he said.

Who placed the story, Kerner wanted to know. I did, Hannum told him. This was the beginning of the end. Kerner, now even more concerned about Hannum’s challenges, still offered him a one-year contract for this season, with another raise. Hannum said no.

They negotiated further over the long-distance telephone, and both stubbornly held out. “I can’t take the job,” Hannum said. He wanted the same money Auerbach was getting from Boston—and it had to be for two years. What, Kerner wanted to know, was Auerbach getting, and when Hannum told him—he may or may not have been correct—Ben said, “I’m surprised. I thought he was getting even more. He’s been a coach in this league for a long time, ever since the beginning. But do you think you’re now on a par with Auerbach? Why, you’ve just finished your first full year as a coach. Give yourself some time.”

Their conversation closed, Kerner thought, with Hannum refusing to accept a contract. He would not be back.

Kerner stewed over his problem for a while. To announce that the coach of a title-winning team was resigning meant considerable explanation and doubt and confusion. It was not good business, he knew, but neither is it good business to permit the coach to dictate terms. Finally, he decided he would have to carry it out. He had a letter of resignation prepared, called Hannum long distance, and read it to him. Hannum said he liked the way it had been worded—the announcement did him justice—and it was okay with him to release it to the press.

Then, when the newspapers got hold of the story, they called Hannum in California for comment. “What are you talking about?” he said. “I don’t know a thing about it.”

This disturbed Kerner. He had witnesses to his conversation with Hannum, but he refused to use them unless he was compelled to. Reporters called Hannum again that day, and this time he said he had meant that his resignation was not final and that “the door was still open to resume negotiations.” But Kerner responded that the door was shut.

****

Soon afterwards, Ben called his players together for a three-day vacation and consultation in Miami Beach, on him. He was going to ask them whom they wanted as coach. But before going down there, he again contacted Phillip. “Look, an offer might be becoming,” he said. “But I want to know first what your reaction would be.”

“I’d be interested,” Phillip said.

Kerner’s task at Miami Beach was to learn the feelings of his players. It is not a simple matter to find a suitable coach in the NBA. Because of the long schedule and constant traveling, it is not a job for an older man. Because of the brief preseason training period, there is time only to get a team in shape, not to teach it a full system.

Generally, none of the players wanted a college coach. The big men wanted a big man, the little fellows a little fellow. And all of them were in favor of Andy Phillip.

So Kerner went for the quiet, experienced, intelligent pro. Boston willingly released him under the one condition that the 36-year-old backcourtman refrain from playing. The famous pre-war Whiz Kid of the Illini comes from Granite City and is well-known around St. Louis. He is a good listener, a sound basketball man, and, being only one year removed from the pace of the pro circuit, won’t mind the travel and night flights and living out of a suitcase.

“You’re in a tough spot, taking over a champion team,” Kerner told him.

“It’d be tougher taking over a loser, wouldn’t it?” Phillip answered.

At the start of the season, Kerner said, “I’m willing to say this. If this fellow can’t do it for me, then no one can.”

So, for the first time in his career, Kerner felt ready for a season, with a good team, a promising coach, a happy town, and money in the bank. It was a fantastically far cry from the beginning. Kerner was publishing sports programs for wrestling, stock car racing, and the like in his hometown of Buffalo when the old National Basketball League began to expand with the post-war boom in 1946. He thought it would be a good idea to get in. “It cost next to nothing to get a team started in those days,” he says. “What I pay Pettit and Cliff Hagan now is more than my total payroll for everybody and everything, only six years ago in Milwaukee.”

With no pro draft in those days, he went out and signed up college players and old pros from the Eastern League and even a few from the pre-war dance hall teams. “My first coach,” he says proudly, “was Nat Hickey, the old Original Celtic.”

In the middle of that first season, he moved. He had a bad club and a bad schedule. “We were the sixth sport in town, behind boxing and wrestling and college basketball and American League hockey and even the stock cars,” he says. “I was given playing dates on Mondays and Thursdays, both shopping nights in Buffalo. I didn’t have a single weekend date. It was terrible. I’m ashamed to say what we drew.”

Business picked up slightly at Tri-Cities. “Not that it was good,” Ben explains, “but I didn’t get hurt too badly because my overhead was so small.” While he was at Tri-Cities, the war with the new Basketball Association of America got started.

“It was survival of the fittest and what was now a 17-team National League. Franchises dropped like flies, first to 12 teams and finally to eight. But who ever wins in a war anyway? I was in Tri-Cities four years, and I just managed to stay alive. That was always my history until, thank goodness, St. Louis.”

Without large outlays of cash to back him, Kerner always had to sell, deal, trade—and scrounge—to stick. He sold Frank Brian to Fort Wayne for $18,000, and Mel Hutchins to the same team for $30,000, an amount he believes is the largest cash transaction ever negotiated in the league. “In 10 years, I sold $100,000 worth of players,” he says now. “That’s no way to build a team, but it got me needed working capital to pay my bills and stay in business. Since we’ve come to St. Louis, I haven’t sold one player for the sake of money.”

At times, when there were no salable ballplayers available, he mortgaged his home and his business and took a loan on his life insurance policy, but he never missed a payroll. This is an article of some pride with him—and with his players.

In 1951, with the league down to 10 teams, large cities began putting pressure on the NBA to come in. And Kerner went to Milwaukee, an available big city with a new building. He got there two years before the baseball Braves did and left two years after the Braves arrived. “That last year in Milwaukee was the worst I ever had. I lost $36,000. I couldn’t sell players anymore. I knew that if I did, I might just as well get out. The league was getting big now, and so was the overhead. So, I decided to build.”

That last year in Milwaukee was the turning point for Ben. In the college draft before the season, he got Pettit after Baltimore, picking first, took Selvy. Later, when Baltimore folded, Kerner got Selvy, too, in the pro draft.

When he first acquired Pettit, Ben made a prophetic published observation: “This kid is the greatest,” he said, and the newspapers printed it. “If we stick together long enough and my money holds out, he’s going to win me a league championship.” Four years later, in the last game of the playoffs, Pettit scored 50 points, a record performance, and he won Kerner the league championship.

While he was finishing out that last season in Milwaukee, Kerner knew that he had to leave town. On the road, late in the season, rookie Selvy set a scoring record, and then the team came home to play the Celtics on a Saturday night. Still, they failed to draw a crowd. This convinced Ben that he was licked. The Braves had taken over all of the available sports business, he decided, and he began looking elsewhere.

As an experiment, he booked the team in other cities. In February 1955, he played one of these test games in St. Louis. Everything was against the doubleheader he had arranged—Cinerama opened in town that night, the strong-drawing show, Oklahoma, was playing. St. Louis University was meeting popular rival Bradley, and it was Ash Wednesday. Still, the doubleheader drew 7,500—in the snow. The next season, the Hawks settled in St. Louis and, at last, had found a home.

They should remain there for a long time. The current championship team is young and talented. Pettit, who wants to be the greatest player there ever was, gets them the ball at one end of the court and puts it through the hoop for them at the other end. This is difficult work, and nobody in the league does the combined job as well as he does.

Cliff Hagan, Li’l Abner to his friends, has a fine scoring “touch,” desire enough to mangle people for the ball, and a deadly jump shot. Martin, the old pro and the most-popular man in the league among the players, is the team’s leader. He brings the ball up, gets the team moving, and keeps it running. “Our club,” says Pettit, “cannot function without him.” McMahon, the other backcourt veteran, has shown a wide strain of unselfishness. He gets the ball into the pivot effectively.

And behind these two are Win Wilfong, the No. 1 rookie in the league last season, and Al Ferrari, an exciting ballplayer who “can eat you up.” He returned from service last summer. Macauley, the popular hometown hero, comes off the bench and maintains the shooting pace up front. Although past his peak, he is highly serviceable in this role. Charley Share, the big fellow who relieves Pettit, has been with Kerner the longest and is a tough man to handle under the boards. Then there are rookies Dave Gambee and Hub Reed and Jack Stephens and Julius McCoy back from the service. And Clyde Lovellette, the big fellow he got in a trade with Cincinnati in September. The Hawks have depth this year, too.

And Kerner? Well, he has chartered a DC-3 for his team’s private use. And he bought them special suits to wear when they travel around the league, on the style of the outfits the Braves and the San Francisco Giants began using this summer. He has consigned a budget of $53,000 for outside promotions this season, like booking Louis Armstrong, Lionel Hampton, Duke Ellington, and George Hamilton IV for halftime shows. He is in favor of the players’ association. He is charging the lowest prices in the league for his attraction, with a top of $2.75. And he still drives a low-priced car through the dark streets of St. Louis on sleepless nights.

But when it is over, after he has worked 12 months a year and has taken no vacation . . . and has spent money . . . and has worried . . . and has nursed ballplayers—after all this, he remembers the one important fact. “When the season starts,” he says, “what I have and what I am doesn’t count. I got to turn it all over to five guys wearing $6 pairs of sneakers.”

Could you tell me the name of Bob Pettit’s autobiography

LikeLike

It is titled Bob Pettit: The Drive Within Me. The first printing was in 1966.

LikeLike