[We ran an earlier post about the Continental Basketball Association from 1980, and it included a brief section on NBA journeyman Brad Davis. Well, the journeyman tag didn’t stick long. Davis settled in around that time with the expansion Dallas Mavericks and stuck with them through thick and thin over 12 productive seasons. The Mavs even honored Davis several years ago by retiring his number 15 as thanks for the memories. At last count, Davis still lives in Dallas and still works for the Mavs.

But Davis’ happy ending almost never came to pass. He’d been knocked around by the NBA one too many times and was determined to call it quits for his self-esteem. This article, published in the February 1982 issue of Basketball Digest, explains Davis’ frustration and reluctant decision to give his NBA career one last shot in Dallas. DaJere Longman, then with the Dallas Times Herald, tells Davis’ story.]

****

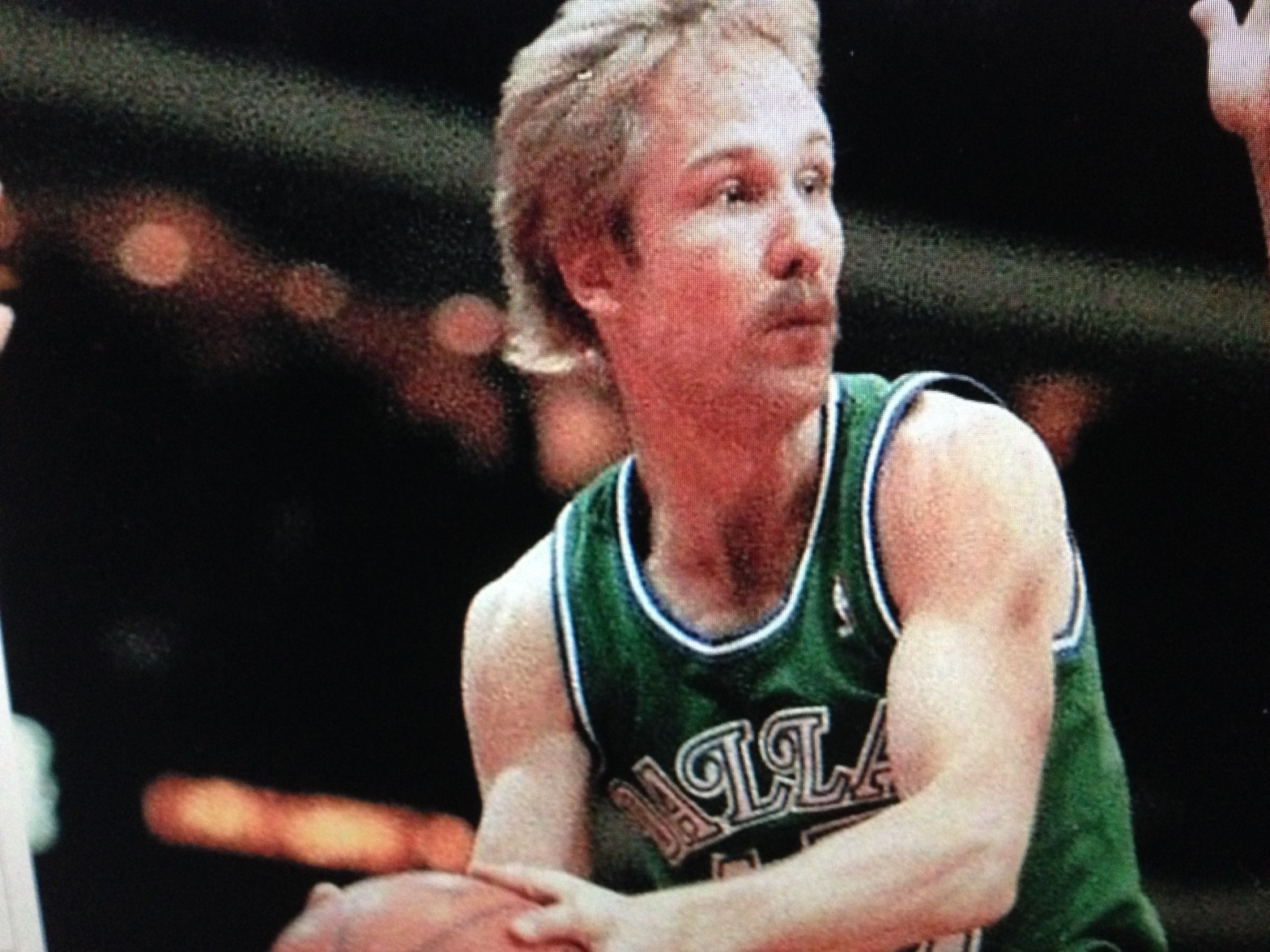

Scotty Robertson is giving Brad Davis one of those character talks coaches always give their players. Or ex-players. They are at shooting practice before a Dallas-Detroit game. He is trying to convince Davis that four years in the NBA with five different teams will make him a better man. Davis is not eager to hear this. Robertson’s words glance of him like a foul tip.

Davis doesn’t want to hear that crap anymore. He knows he can get great money, good hours, and the discipline of the team accomplishment out of sports, and he wants to leave it at that. He is no longer young and idealistic and fresh out of Maryland and a first-round draft choice of the Los Angeles Lakers. Once his pocketbook was fat, and the good life was forever. Now his dreams stop at the next trading deadline.

He is ambivalent toward Robertson. He is thankful for the tryout chance in Detroit two summers ago, the last chance he thought he would ever get. He is disappointed because he played well for the Pistons and was cut the day before the season started. Cut even though his teammates needed his passing and wanted him around. Now he is in Dallas. He puts his hands on his hips and listens, eyes searching the Reunion Arena floor, a little embarrassed. He must go on listening to Robertson’s talk.

“A lot of things happen in this league. You gotta make the best of them. It’ll make you a better person,” Robertson tells him.

He sounds like George in Of Mice and Men. He sounds like George telling Lenny about the rabbits and living off the fat of the land.

“All those guys that made it to the top right away, like Magic, they think this is the easiest thing in the world,” Robertson continues. He has been bounced around, too. New Orleans, Houston, now Detroit. “Sure it is when you play with guys like Kareem. They ain’t been cut like me and you. It’s hard. But stay with it. It’ll make you a better man.”

For four years now, people have been telling Davis to stay with it. To wait his turn. That it would be all right. That he couldn’t miss.

It has not been all right. The Mavericks had to coax him out of retirement. It has not been all right attending more tryouts than a Broadway chorus girl. It has not been all right changing uniforms like socks. It has not been all right stowed away in the Continental Basketball Association, struggling in an outpost like Anchorage, waiting for another chance.

Davis has another shot. His fifth. When Geoff Huston had been traded to Cleveland, he was left to run the Mavericks’ offense at point guard. Starting over. He is not yet comfortable. He wants, expects, not stardom but simply minutes. P-T, playing time. He wants to get off the roller coaster. He does not want his career to be a perpetual tryout. He wants, he says, to be on an even keel.

“It’s all new to me,” he said of his starting role last season. “It’s been so long since I’ve been out there for a jump ball at the beginning of a ballgame, it’s unbelievable.”

Davis started the final 26 games for the Mavs. They were 8-48 in the first 56 games, and 7-19 in his 26 starts. He led the Mavericks with a 6.9 assist average and in field-goal percentage (.561). Davis notched 11 games with double figures in both scoring and assists in the same game. He scored a Dallas-record 31 points and sank 11 consecutive field goals in a 117-105 loss to Boston. Following the Huston trade to the Cavaliers, Davis averaged 17.4 points, 9.3 assists, shot .595 from the field, and .831 from the foul line playing 39.3 minutes per game.

After joining the expansion Mavericks in mid-December, he was the team’s most-consistent playmaker, although Huston continued to start and log more playing time. Dallas coach Dick Motta says he had never seen a player pick up his offense so quickly. In 13 years, he says, he has had few players run his offense more efficiently.

“He came in here with no playing time and no confidence and picked up the offense as fast as anyone I’ve had,” Motta says.

He is a classic playmaker, 6-feet-3, 180 pounds, with Orphan Annie hair and unselfish style whose job is to run the break and get the ball to his teammates in the pattern offense. While he is not the scorer that Huston was, he is a better passer and is more adept at pushing the ball up the floor.

“He makes you want to run harder because you know he will get the ball to you if you’re open and get it to you at the right time,” says forward Tom LaGarde. “There’s a difference between passing the ball and passing at the right time. Brad has great timing. He is especially good on the break and penetrating the middle. It’s tough to come into a situation like he came into. When things don’t go your way, it’s a struggle. He’s really come along great.”

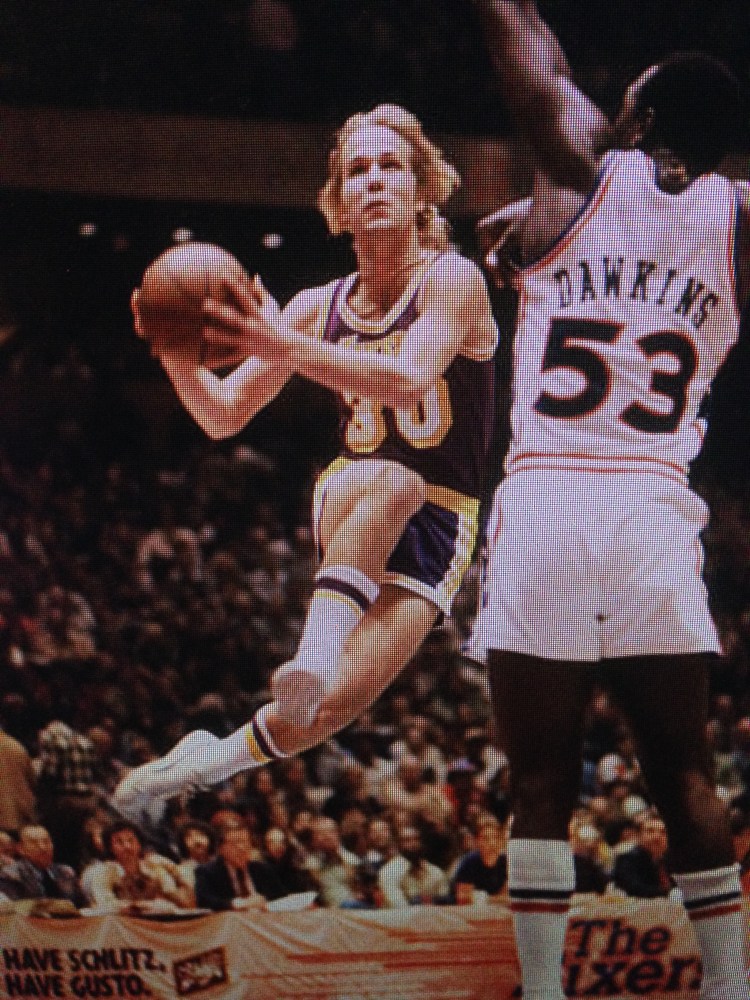

Lured by the siren of first-round draft money and the chance to play for Jerry West, Davis went hardship in 1977, leaving Maryland after his junior year. He was hell on the fastbreak. He was All-America, a “can’t miss” prospect. Unfortunately for him, the Lakers had three first-round choices that year. Norm Nixon couldn’t miss either. While Nixon sent the ball to Jabbar like a veteran, Davis and his fastbreak talents rode the pines for all but 334 minutes.

He was waived in October 1978, and he got a rep. He was said to be uncertain on the break now, an average shooter, questionable on defense. Perhaps not quick enough. He had a quick bite to eat in Indiana in 1979, then was waived again. He was a role player. The same commodity that would make him invaluable in Dallas, ironically, was contributing to his early transience.

“You see guys like Brad move around the league because a lot of times role players depend on the luck of finding a club that can use your skills,” says Dallas assistant Bob Weiss. “They’re not a guy that’s going to turn your around. But they may be a piece to a puzzle that fits perfectly with some team.”

Davis had the dreams of every other kid out of college. He wanted to play five or 10 years in the same town, the way John Havlicek played in Boston and Walt Frazier in New York, then retire and go into business in that town. He does not regret leaving college early. The money was right for him then.

Quickly, though, the hopes faded. He would never be another Jerry West. He couldn’t control his frustration. His parents could tell how upset and disgusted he was on the telephone, and how much confidence he had lost. His wife had to endure solemn rides home from the Forum. His only escape was to run the beach at night.

“I didn’t like myself,” he says.

“There were some low points. All the times I was getting released and not getting any playing time. You wonder if it’s worth it. The money’s good, the hours are great, it’s a great profession to be in. But it takes its toll on you mentally. When you feel like you’re good at something, when you’ve worked your whole life to get where you are, and somebody says you can’t play anymore, with their club at least, it’s disheartening.”

After Los Angeles waived him in October 1978, Davis was exiled to Anchorage in the CBA, a sort of Siberian minor league. At first, he played stiffly. His shot was tentative, his selection poor. His NBA experience had unnerved him. “Someone had convinced him in L.A. that he couldn’t shoot,” says his Anchorage coach, Bill Klucas.

Suddenly, he found himself playing in a high school gym on a meager $10,000 contract and washing his own uniform. His team was on the road for a month at a time, playing in Hawaii one night, then catching a 1 a.m. plane to the mainland for a connection to Bangor, Maine. Gone were the ribeye steaks. A $12 per diem meant lunch and supper at Wendy’s and McDonald’s or a hotel buffet. The civic auditorium crowds seldom surpassed 4,000 and often slipped to 300.

“Some of the hotels were okay, some were dives,” he says. “A couple looked like they were out of a 1955 B-movie with the neon and all that. Travel was the hardest thing. You’d spend a day and a half flying and waiting in airports. I don’t remember a lot of funny times. You spend most of your time sleeping or reading the box scores seeing how certain guys were doing at your position or with the team you played with formerly. For me, that was about five teams I had to look at. You always check the injuries and transactions to see where people are going.”

Indiana picked him up in February 1979, but released him eight months later. This time, he ended up in Butte, Mont. for a cup of coffee before the roller coaster ride brought him to Utah in February 1980. He appeared in 18 games that year, finishing with 50 assists and 83 points (4.6 avg.). When he asked Utah for security in his contract, they offered only the minimum salary. So, he didn’t return. Instead, he was invited to a tryout camp in Detroit. He thought he performed well, but was dropped on the final cut.

“I think he ran into a problem because some people had some guaranteed contract money,” Weiss says.

Detroit was to be his last shot. He was tired of the gypsy life. He wanted some stability. He had grown weary worrying about his residence from week to week. A 10-day contract with Kansas City was turned down. He had been 10-dayed to death. For a second time, he headed to Anchorage. The plan was to play until the spring semester began at Cal State Northridge, then return to school.

In December, the Mavericks came calling. In two days, they talked three times. Davis wasn’t interested. “We called him and got a very surprising answer,” Weiss says. “Usually, these kids say, ‘I’m packing now.’ Brad said he wasn’t interested in playing basketball. We hung up and said we really didn’t want to kid who wasn’t hungry and doesn’t want to play. Then we got curious about why he didn’t want to play.”

Weiss called back, and Davis said he was tired of knocking around. He was disillusioned, ready to call it quits. He said no again. Weiss called back a third time, at 6 a.m. He told Davis he could sign a contract for the remainder of the season and quit anytime if he wasn’t satisfied. If he wanted to return to school after two or three weeks, there would be no hard feelings. This time, Davis consented. “It was too early in the morning to say no,” he says.

Things are going well now. Davis says he tries not to reminisce about his failures. “I try not to put the blame on anyone in L.A.,” he says. “I try not to look back and point fingers. It’s been four years, although it seems like a lifetime, and I try not to look back. I just figure I was in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Nor does he look much further ahead than the next game. He enjoys running Motta’s offense, but he has been burned too many times, been disappointed too much, to feel his job is anything but tenuous. Some call him cynical, distrustful. He prefers to call it realistic.

“I’m conscious of what’s going on,” he says. “That comes from being bounced around four years. I don’t want to get hyped up at this point. I would just like to go on an even flow for once. Things are going pretty well so far, but that could change in a minute, so I take it day by day. I feel I have to play each game to the best of my ability just to stay here.”

So when will he be able to feel at home? “Give me about four years here,” he says, chuckling. “Maybe that’ll do it.”