[Just to be clear, the headline above doesn’t refer to Bill Laimbeer’s greatest hacks and cheap shots of 1988. We’re referring to the many articles written about Laimbeer and the Bad Boys of Motown from that year. We’ve got four greatest hits to share. Think of it as an extended play (EP) post, not a full double-sided LP.

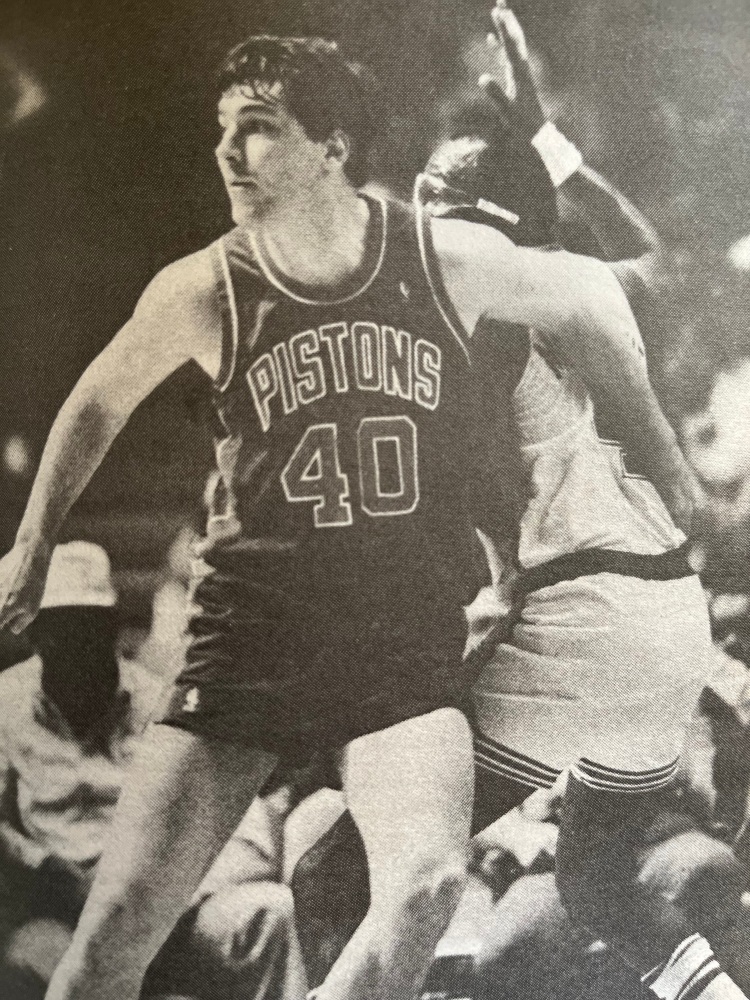

Let’s start with our first selection. It’s a general overview of Laimbeer for anyone who may have come to the NBA after his career. This first selection comes from the April 1988 issue of Basketball Digest and penned by Marc Hoffman. His article ran under the well-stated headline: Bill Laimbeer: A Mule Among Thoroughbreds.]

****

Chuck Daly remembers the first time he saw Bill Laimbeer play basketball. “It was the 1980 Olympic Trials,” remembers Daly, the coach of the Detroit Pistons. “Everyone pretty much agreed that he was the worst player there.”

A lot has changed since Laimbeer, now the Pistons’ center, was cut from the Olympic team. He’s averaged more than 15 points per game in each of the last four seasons and better than 11 rebounds per game each of the last five. He’s played in four All-Star games.

“I can’t tell you how he does it,” says Daly. “He’s 6-feet-11, but he can barely dunk. He can hardly jump over the lines painted on the floor. He’s got very slow feet. And he’s got no post–up moves to speak of.”

Daly smiles and shakes his head. “Yeah, he’s made himself into quite a player.”

Laimbeer is definitely a self-made player. In a world of thoroughbreds, Laimbeer is a mule. And he doesn’t wear blinders. “I get the most out of my ability,” he says. “I outhustle everyone. I play harder than anyone, that’s how I get by. I don’t have the natural ability most of these other guys do. I’m not a shot-blocker I don’t do any monster dunks. I’m not flashy.

“I’m not going to match moves with Michael Jordan and Dominique Wilkins. I learned a long time ago that I am what I am. I am a blue-collar player.”

He’s a mule, though many would substitute the more vulgar synonym. There probably isn’t a more-hated player in the league than Bill Laimbeer. “No, I sure can’t think of one off the top of my head,” says New Jersey forward Roy Hinson.

“His reputation precedes him, that’s for sure,” says Bulls forward Brad Sellers.

A rookie last year, it didn’t take Sellers long to see for himself. The Bulls and Pistons came to blows several times last year and again this year. On at least two occasions, Laimbeer boiled the bad blood by knocking Michael Jordan into the basket support from behind on breakaway dunks.

“Bill Laimbeer’s a cheap-shot artist,” Hinson says flatly. “He grabs you, he pushes you, he elbows you. And he whines a lot. He’s the master of the flop. [faking a foul]. He should invent a new dance: The Laimbeer Flop.”

Cavaliers center, Brad Daugherty won’t be going to dinner with Laimbeer either. After an early season game with Detroit, Daugherty exploded when I asked about Laimbeer. “It’s no damn war with him out there,” he said. “Don’t make him out to be a tough guy. He’s a damn baby; that’s all he is.”

Confronted with his reputation, Laimbeer is undaunted. “Hey, I hear that all the time,” he says. “When I’m out on the court, I have a job to do. I play a certain way, and I can’t worry about whether people like me or don’t like me. People don’t like the way I play because most guys want to run and shoot jump shots without anyone touching them. They can’t do that when I’m on the floor. I’m going to bump you, push you, and bang you.”

“The other guys in the league may hate him, but they’d love to have him on their team,” Daly says. “No, he’s definitely not a popular guy around the league. He irritates people, they get mad, and Bill just smiles and walks away. He’s such a tough–minded, stubborn guy. He is one of the most–competitive people I’ve ever met.”

“He’s a different type of player,” says Laimbeer’s college coach, Notre Dame’s Digger Phelps. “He’s not afraid to be physical, to be aggressive, to step in and take a charge. That gets misunderstood, but that’s his personality.

“But off the court, you couldn’t find a better person. He’s been good to his family, his school, the community. He’ll do anything for you.”

Laimbeer concedes that he is “a completely different person off the floor than on it.”

“Basketball has never been the most dominant thing in my life, and it never will be,” he says. “Basketball is my job. It’s how I earn my living. It’s not my whole life. I don’t act at home the way I do on the basketball court.”

His family, no doubt, is thankful for that.

[Now, that we’ve got things rolling, track two is the great Harvey Araton of the New York Daily News. He wrote this classic piece during the 1988 Detroit-Boston playoff series and grudge match. His story, which ran in the Daily News on May 27, 1988, appeared under the headline, “Boston is Laimbeer’s Combat Zone.” Enjoy.]

Boston—The movies are a good place to kill an afternoon. There is one of those multi-theater complexes in a mall next to the downtown hotel. Bill Laimbeer likes to slip into a seat, hopes the lights are dim right away.

Walking the streets is out. He is a big, burly man, and can take just about anything inside of a basketball arena, but who needs obscene verbal abuse in the middle of a sunny afternoon? Who needs the finger-pointing? Who needs to be a target of hate in the middle of Boston?

Boston hates Bill Laimbeer, probably more than it hates any single Republican. He, more than anyone else, is the personification of the Detroit Pistons. The Celtics do not like the Pistons, not even a little bit, which means the man in the street, likes them even less. Which further means your average Bostonian would love to take a boot heel to Bill Laimbeer’s Boy Scout face and turn it into a road map of Massachusetts.

“We were talking the other day about how they hate me here, and I said, ‘What if the lights go out again in the Garden while we’re out on the floor?’” Laimbeer said. “One of the guys said, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll sandwich you, make sure nobody lays a hand on you.”

He is despised here more than any player I can recall in the nine years since Larry Bird showed up and we all started buying hotel time shares for these annual late spring playoff festivities. Besides being a general physical nuisance with that snotty, fresh–faced look, Laimbeer did the unthinkable: Ralph Sampson may have punched Boston reserve Jerry Sichting, but Laimbeer hammered Mayor Bird to the floor in last year’s Eastern Conference final. Deposited him there like a bag of balls.

Bird—on the wall of his Garden locker stall is a picture of Laimbeer swinging a golf club with a head shot of Johnny Most pasted over Laimbeer’s face—hasn’t forgiven him. Boston will never forgive him. He knows that, accepts that, uses it to generate some hate of his own.

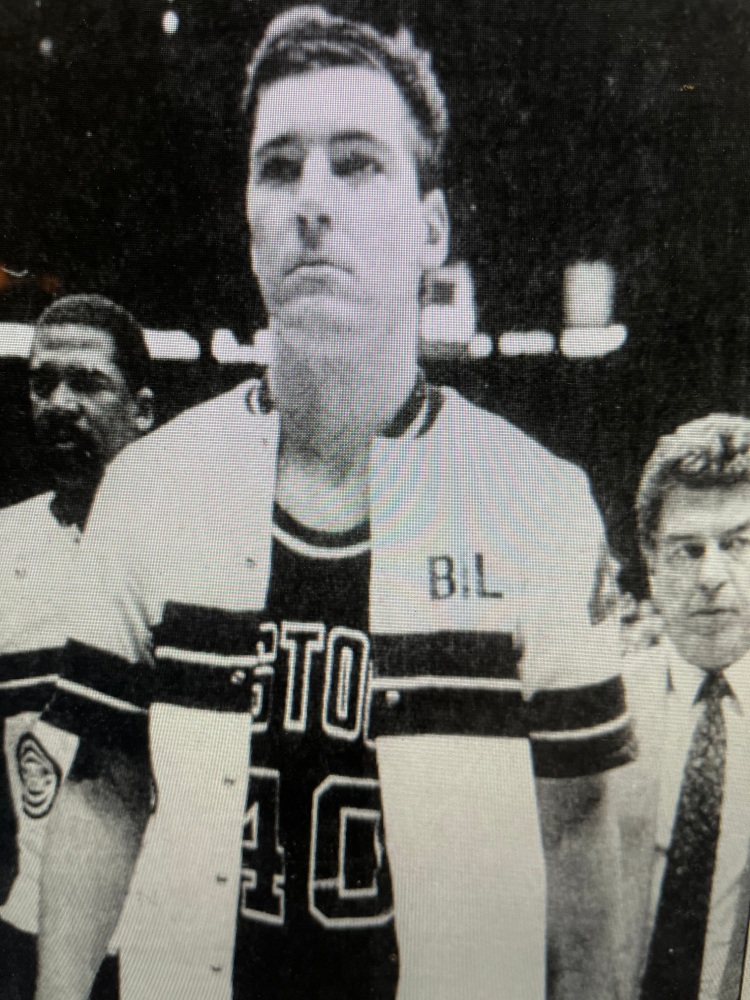

Remember the game face Bernard King used to put on when he was a Knick, the one that made mothers grab their children to make a run for the blue seats? That was Laimbeer, when he was announced with the other Piston starters before Detroit’s 104-96 victory Wednesday night in Game One. The crowd booed . . . louder . . . louder . . . so Laimbeer, palms upturned, wiggled his fingers telling these people, “That the best you can do?”

The Celtic starters were coming out now. Laimbeer, leaving the Detroit huddle, walked toward the middle of the court. He was on his toes, a fighter in his corner, awaiting the opening bell. He stared. Out came Danny Ainge, Dennis Johnson. Laimbeer stared. Out came Robert Parish, Kevin McHale, finally Bird. Laimbeer stared.

“Who was that for, you or them?”

“That was for me.”

“For what?”

“To get focused. To remember who they were, where we were.”

“Did he do that?” Vinnie Johnson said. He shook his head and laughed, “I didn’t see that, but I’m not surprised. That sounds like Bill.”

Laimbeer did not figure much in the big Pistons win Wednesday night, the one that broke their 21-game losing streak in this heretofore Temple of Doom. He hurt his shoulder during the second quarter going for a rebound, felt excruciating pain, left for the locker room in the third quarter, and stayed there for the rest of the game. He was feeling better by yesterday morning, ready to play in Game Two last night.

You couldn’t find his mad-dog look in the box score, but it said as much about the Pistons Wednesday night as the final score. This time, it said, they were here for serious role-up-the-sleeves, Wall Street business. They were here this time with game faces. People said they celebrated too soon last year. Wednesday, when Dennis Rodman came dancing down court in the final minute, the assistant coaches jumped off the bench screaming, and Isiah Thomas was in his face.

This is business. Game faces at all times. “I was in here, and it was on TV, but I couldn’t watch, “ Laimbeer said. “I sat here trying to figure it out by the crowd noise.

“I could tell when they had the ball, when we had it. I’d count down the 24 seconds, and when I heard that groan, that ‘Ohhhh . . .,’ I knew we’d scored.”

When it ended, he didn’t know the final score, didn’t know about Isiah’s 15 fourth quarter points, only that the Pistons had their precious road win. He waited by the door, and when the security guard pushed it open from outside, Laimbeer, an ice pack on his right shoulder, held his left hand high. One by one, the Pistons reached up to it. There was still fire in his eyes.

[Track Three? Let’s go to the June 9, 1988 edition of the Detroit Free Press. The great Mitch Albom is waiting. He’s been in Los Angeles for the NBA final between the Pistons and Lakers. Albom decided to take a side trip to Laimbeer’s privileged Southern California neighborhood. Here’s what he found.]

Palos Verdes, CA—I am walking past the cliffs that drop into the Pacific Ocean. I am walking next past the Corvettes, and the BMWs, and the dark-blue Mercedes. I am walking past the tennis courts and the long turquoise pool.

I am walking into Bill Laimbeer’s old high school.

His high school?

“Do people really go to class here?” I ask Laimbeer’s former coach, John Mihaljevich, 52, who greets me dressed in a red windbreaker, sunglasses, shorts, and a deep tan. “Do they actually study, you know, math and science and all that?”

“Oh, yeah,” he says. “All that.”

All that. All this. I am seeing ocean views and red-tile roofs and birds chirping an expensive tune. I am seeing palm trees and coiffured lawns, and driveways that disappear into . . . who knows? High school? Can that be right? Are they sure this isn’t a hotel?

I had heard all the stories about Laimbeer, the Pistons’ center who had recovered from a sprained arch well enough Thursday to return to Game Two of the NBA finals against the Lakers. Laimbeer had told me many of the stories himself: How he was the only player in the NBA who made less than his father. How he never worked a day in his life. How he had a new car on his 16th birthday. Palos Verdes High School. A privileged upbringing. I was never sure how much he was kidding.

“What do houses go for around here?” I ask Mihaljevich.

“Four to six million,” he says.

He wasn’t kidding.

This was not the way I went to high school. We did not have an ocean. We did not have cliffs. Cliffs would be bad for the bicycles.

Here there are cliffs. Out in the distance, you can see a sailboat. I look at the students who are walking through the schoolyard. Actually, it is not a schoolyard, it is more like a campus. Actually, they don’t look much like students either. They look more like the cast members from Less Than Zero.

But back to Laimbeer.

“So tell me,” I say to the coach, taking a seat in his office. “Was Bill a good kid?”

“Oh, yeah. He was a good kid. I have to say Bill’s approach to life was to do as little as possible in the easiest way possible. But he was a good kid.”

“Did he ever get into trouble?” He pauses. “Well, once, during his senior season, we were in this all-star tournament, I think it was in Kentucky. And the bus was leaving for the game. I asked around, ‘Has anybody seen Bill?’ Nobody had, so I went looking for him.

“I went up to his hotel room, he wasn’t in it. Then I saw this other room, and the door was open. I looked in, and there was Bill playing poker with all these strangers. Grown men! And here was this 18-year-old kid.”

He smiles. “After that, I started to think maybe there was stuff Bill did in high school that I never found out about.”

There was the time Laimbeer broke his arm playing football his freshman year, and the time the coach yelled at him during a Christmas tournament, and Laimbeer started crying. There was the time, lots of times, really, when the opposing teams said of the Palos Verdes Sea Kings, “Let’s beat these rich kids from the hill.”

There was a time when Laimbeer took his SATs and scored 1,000, and the recruiters said “Great! That’s unbelievable! No problem!” and Laimbeer’s friends said, “One thousand? Too bad. Maybe you can take them again.”

How strange to hear these stories. Most of us in Detroit, know Laimbeer only as the center for the Pistons, a man who gets the most out of limited physical skills, a man considered the most-hated man in the NBA. On TV lately, during these NBA finals, he has been labeled “The Villain.”

Here is where The Villain went to high school. “I’ve got some photos of Bill when he was here,” Mihaljevich says, pulling some photos from a yellowing file. “This was during the California state championships. That was his biggest game. His senior season. We upset a team that was ranked No. 1 in the country.”

“Wait a minute,” I say, holding up the black-and-white picture. “He’s shooting . . . a hook shot!”

“Oh yeah. Bill had a great hook shot. And a good pivot to the basket.”

I stare in disbelief. “You mean he was . . . a post-up player?”

“Strictly. I never let him shoot more than eight feet from the basket. If he did, I’d break his neck.”

Somebody get me the smelling salts. Are we talking about the same Bill Laimbeer? The guy who treats the offensive backboard the way a housefly treats a Shell No-Pest Strip? That Bill Laimbeer? Top-of-the-key jumpers? Perimeter passing? That Bill Laimbeer?

“Yes. All the outside shooting came after he left here. Sometimes I would catch him in the gym, you know, after practice, and he was shooting jumpers, and I’d yell at him. ‘What are you practicing that stuff for?’

“My theory is, he has the mind of a point guard trapped in the body of a center.”

I mentioned to the coach how Laimbeer brags about never having had to work in his life other than basketball. “That’s not true,” says a man overhearing our conversation (I believe he was an English teacher.) “There was a summer where he got a part on a Saturday morning TV show for kids. It was called Land of the Lost. He played a monster. Him and a couple of other basketball players. They were called Slee Stacks.

“A monster?” I say.

“Yep. I remember telling my daughter who watched the show, ‘Hey, see that monster? That’s Billy Laimbeer from the high school. She asked me to get his autograph. He signed it ‘Bill Laimbeer, Slee Stack.’ That may have been his first autograph ever.”

A monster? A TV show? I leave the high school, walk past the Corvettes, get into my car, drive down Paseo Del Mar, and stare at the ocean.

That night, I see Laimbeer in the locker room. He asks me what I thought of the school.

“Pretty, uh, nice,” I say for lack of better words.

“Good view, huh?”

“Yeah. Hey Bill. What’s a Slee Stack?”

He grins. “Oh yeah. It was a TV show. We dressed up in these giant lizard costumes and stalked around making hissing sounds.”

“Hissing sounds?”

“Actually, the hissing was dubbed.”

“Was this a job?”

“Oh yeah. Three weeks worth.”

“How much did you make?”

“Let’s see . . . about $7,000.”

Uh-huh.

After the game, I return to my room. The phone is ringing. It is a radio talk show that wants some input about the Pistons. “What do you think?” the voice asks.

I close my eyes. I see swimming pools and hook shots and giant lizards. I see turquoise pools and sports cars and a poker game in a Kentucky hotel room. What do I think? I think we know very little about these guys, when all is said and done. That’s what I think.

[And our final selection of the post comes from Dan Barreio of the Minneapolis Star Tribune. He wrote this nationally syndicated column in June 1988 during the Pistons-Lakers NBA finals.]

Bill Laimbeer is talking about his image, which among most NBA fans is somewhere between Cro-Magnon and Neanderthal, and he is saying there is no use fighting it. “You sort of get used to it,” he says. “It makes for a good story, you know? ‘The Pistons are a bunch of thugs.’ Some guy in Chicago called us pond scam. It bothered my wife and my mother for a while, but not me. It never bothered me.”

Maybe it’s just me, but I would not want to be called pond scum. Uh, Bill, why doesn’t it bother you?”

“Because I don’t need 200 million friends,” he said. “I don’t care if everybody doesn’t like me.”

That is probably just as well, because he may be just a wee bit shy of that 200 million mark. On a Boston Celtics fan’s Most Wanted List, he is right up there with Jack Nicholson and Pat Riley, and in Chicago, where he has tangled with the untouchable Michael Jordan, he is not exactly revered either.

After Game Four of this year’s NBA finals, Laimbeer was asked whether he ever had seen Lakers guard Magic Johnson so angry. “You mean when he got a little chippy?” Laimbeer said.

Chippy? Laimbeer was going to talk about another player being chippy? A little irony there. For when it comes to being chippy, nobody does it better than Laimbeer (unless it’s teammate Rick Mahorn, the other reason the Pistons have the reputation they do).

Pond scum? That may be carrying it just a bit far. But Laimbeer is indeed very capable of playing the goon. Sometimes he’s a victim of his own image—he is presumed guilty, even when innocent in an altercation—but sometimes the image fits.

And because he has complained on almost all 2,388 fouls called against him during his eight-year pro career, he also has earned a reputation as a whiner.

So, on the Laimbeer image index, here’s what we have so far: A whining, chippy thug on the level of pond scum.

Then there are the people who belittle his athletic talent. In Game Three, Laimbeer twice found himself chasing Lakers about to score on breakaway layups. According to the Laimbeer Image Index, which also states he has the vertical leap of your average five-year-old, there was only one thing he could do: Maim the player about to score a layup.

So, what did Laimbeer do? He blocked the shot. Cleanly. Both times. First, he blocked Byron Scott’s shot, then James Worthy’s. “He goes up, and he looks like Eddie the Eagle,” says Mychal Thompson.

Question to Laimbeer after the game: “Bill, how did you manage to get off the ground and block those two shots?”

“Next question.”

There are days when the image weighs a bit heavy. But Laimbeer figures he has a job to do. “I do what I’m supposed to do.”

At Notre Dame, he got a degree in economics. He understands one thing: They don’t pay him to look pretty. They pay him to bang (and to hit the outside shot).

We can argue with some of what he does, but not with the consistency with which he does it. Laimbeer has played in 646 consecutive regular-season games. He has started 522 in a row. Those are the longest active streaks in the league. “I always tell everybody it is because I don’t jump very high, and I don’t put myself in a position to get hurt,” he said. “I never get into midair where my arms and legs get tangled.”

Even Laimbeer is capable of making fun of the Laimbeer image. “The night before a game, I’ve occasionally felt like I wouldn’t be able to play the next night,” he said. “But I’ve never felt like that when it got to game time. I’ve never even considered not playing.”

Before Game Two, he was listed as questionable because of a strained arch in his left foot. But he played. He always plays. And while we’re at it, we might want to give him credit for consistent production. For the last 522 regular-season games, he has delivered 16 points, 12 rebounds, and 35 minutes a game. Though at 6-feet-11 he has absolutely no inside moves, those numbers are quite solid, especially when one considers he was the 65th player taken in the 1979 draft.

Somebody once asked Laimbeer whether he ever noticed an opposing player trying to end that iron-horse streak on purpose. “That depends if you count taking swings at me,” he said.

At least give Bill Laimbeer credit for always being there to hate.