[Last night, I caught the third installment of the four-part Bill Walton documentary, The Luckiest Guy in the World,” now airing on ESPN. The documentary offers a chance to meet a slower-talking, more introspective Walton, not the wacky, stream of consciousness version on PAC-12 broadcasts. What a joy to see that Walton, through all of his hardships, has found peace and perspective. May he continue on that path for the rest of his days.

Getting-there has been the decades-long hard part. We all know the arc of Walton’s career and its sudden hard stops due to injury. We also remember well that lots of folks back then weren’t happy about his limited play or hardline politics, especially early on in Portland. In this article, published in the Basketball News 1978 Yearbook, Long Island-based basketball writer Bernie Beglane writes about the Big Redhead after Portland’s championship season and the pinnacle of Walton’s NBA career. Like so many stories from back then, Beglane piles on Walton the Tree-Hugger, but celebrates Walton the NBA Superstar—when healthy.]

****

Bill Walton has never felt comfortable with reporters. This was reinforced during his college days at UCLA, when John Wooden, the Bruins’ coach, restricted the access members of the media had to his players.

When Walton would not speak, some reporters let his lifestyle speak for him. Bill’s actions were not that different from those of other students or members of the counter-culture during the early 1970s—his love for the environment, his arrest at a demonstration against the mining of Haiphong Harbor, his letter to President Nixon asking that he resign, his concern for the plight of Blacks and other minorities as voiced in a plea that he not be called a “Great White Hope” in a Black man’s sport.

Bill Walton has come a long way. Walton still has a way to go.

He has become one of the most dominant figures in pro sports. Bill has remained one of its most enigmatic personalities. He is a complex young man, a shy, sensitive person who is wary of any but the closest of acquaintances.

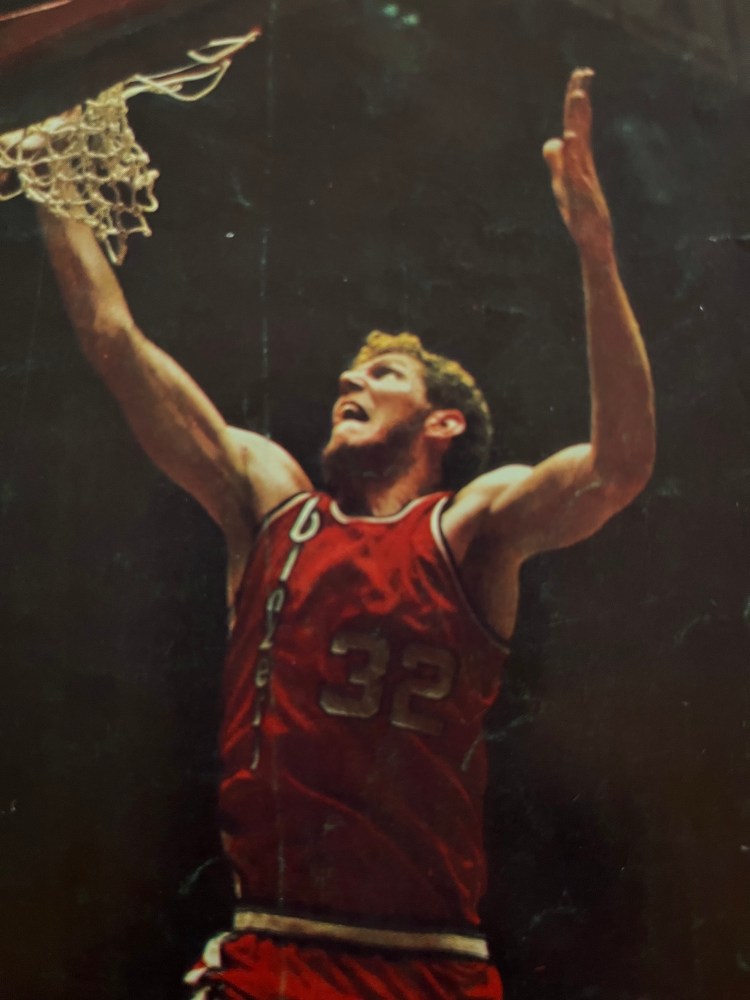

He is in the public eye, but he cannot deal with the close scrutiny. On the basketball floor, he loses all that. Walton is a tremendous player, running up and down the floor, controlling the action at both ends of the court. In practice, he seems completely at ease, engrossed in the action on the court, exchanging wisecracks with his teammates on the now NBA-champion Portland Trail Blazers. Big Bill exhorts them to higher peaks of performance and enjoys himself to the utmost.

In games, he is intense, battling opposing centers for position, jumping high for rebounds, switching over to block the lane and bat away an opponent’s shot, putting up that flip of his that is neither a jumper nor a hook shot, spotting teammates cutting to the hoop and hitting them with passes.

In locker rooms, however, Walton retreats into a shell. He is uneasy talking with strangers, such as newsmen with whom he has not had a long relationship, and rather than try to overcome this, he chooses to fall back behind the psychological barriers he feels he needs to protect himself.

Walton sits in front of his dressing stall and stares down at the floor, treating his chronically aching feet with ice. Reporters surround him and lean forward to hear him speak. However, the words don’t come easily, and when they do come, they are few and far between.

“I don’t want to talk, I don’t have anything to say,” he repeated time and again during the title series against the Philadelphia 76ers.

“Bill doesn’t mean any harm by it,” says Jack Scott, the sports activist who has shared a house with Walton. “He is just a very shy person, and there are many situations in which he does not feel comfortable.”

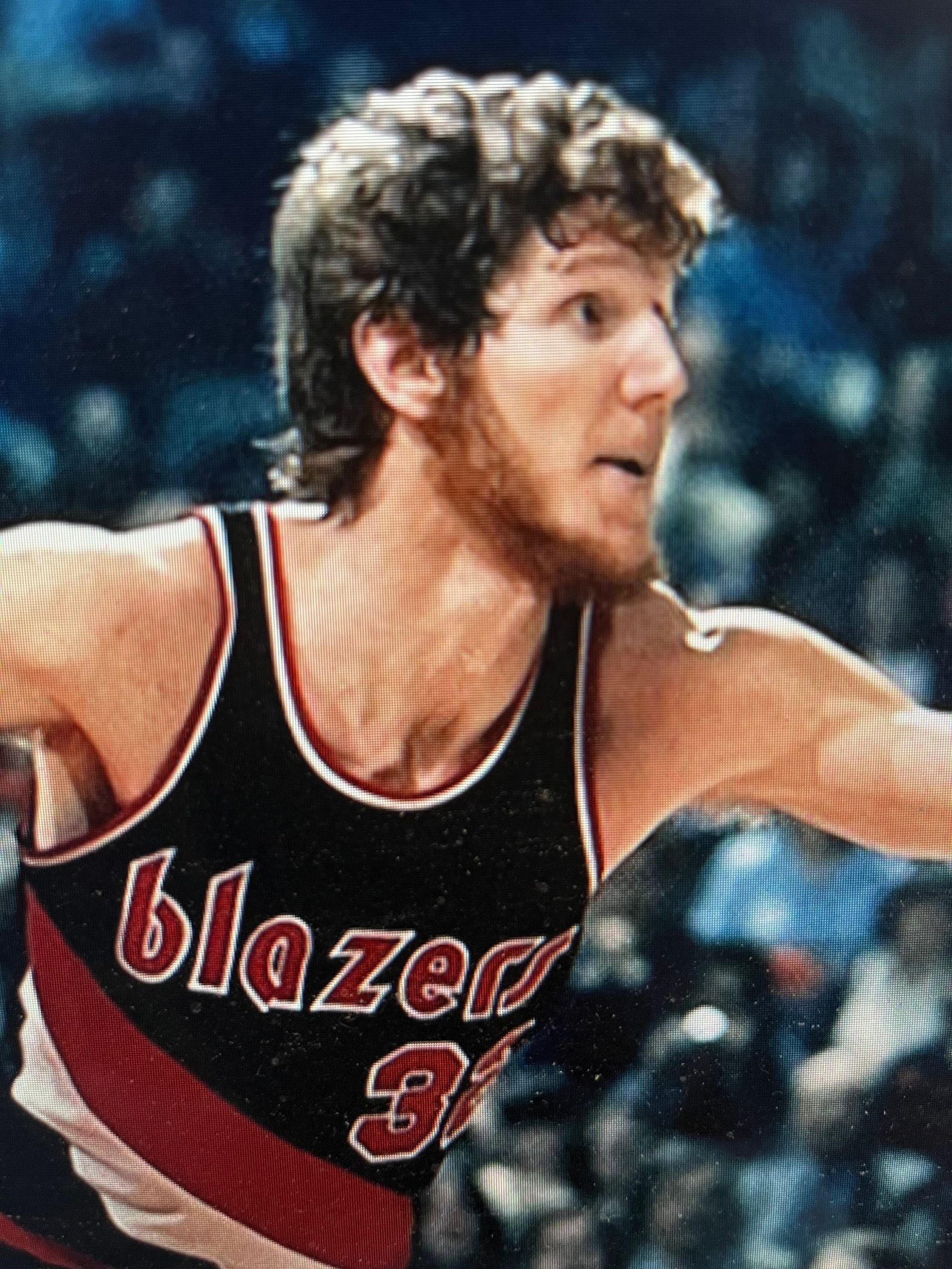

His teammates have accepted Walton, both on and off the floor. This was not the case during his first years in Portland. The club’s established starters, Sidney Wicks and Geoff Petrie, had trouble dealing with the 6-feet-11 center with the long red hair.

“Bill’s our leader,” related rookie guard Johnny Davis. “It’s just in his personality. Bill’s such a great player, he brings out the best in the players around him.”

Some people predicted a conflict between Walton and Maurice Lucas, the talented forward who came to the Blazers from the ABA with the reputation of being a hard man to get along with. It never happened.

“A lot of cats approach Bill differently,” says Lucas. “They think he’s different. Not me. We’re both vegetarians, so we have that in common. We both really like to play basketball. And we play similar type games.”

Walton returns his teammates’ affection and respect. “I like everybody on my team,” he offered. “I love the way they play, the way they act off the court. I respect them, and I respect the coaches.”

The long, fiery hair has been shorn nearly to a crew cut, the scraggly beard has been trimmed. That does not mean any great philosophical change. “Bill works out with weights,” explains Scott, “and between those workouts, practices, and games, he takes two and three showers a day. During the summer, long hair becomes a drag.”

The most important of all of Portland’s draft picks—a total of nine were on last year’s club—was Walton, who was that No. 1 selection in 1974. Ironically, the Blazers won a coinflip with the Sixers, which enabled them to take him. It took three seasons, and a change in coaches, but the Oregon team finally found the players to compliment Bill.

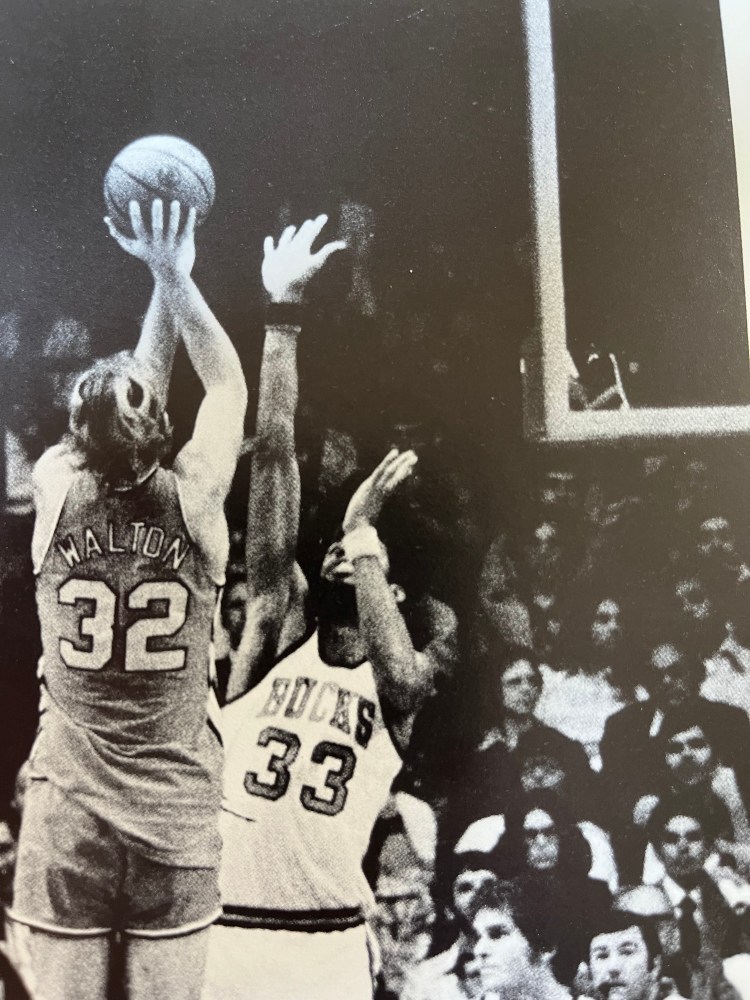

Compared to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar of the Los Angeles Lakers, Walton possesses more overall ability. Abdul-Jabbar is more offensive minded. He is more intimidating on defense. Walton could score 25 points a game, although it would minimize his other assets. He might be the best passer ever to play his position. He is an excellent rebounder and shot blocker. He makes the outlet pass to start the fastbreak as well as anyone has.

After two controversial years, Walton kept a low-profile last season. Injuries sidelined him for most of the 1974-75 season, and some people suggested the pain was more imagined than real. His lifestyle, his political and social views, also brought him negative publicity.

He lives simply, indulging in no apparent excesses. When someone tried to pour champagne over his head after the Blazers had won the championship, Bill slapped at the bottle and it fell to the floor. “I’m no alcoholic,” he muttered.

There are those who believe material things do not concern him, but Walton reportedly does earn $400,000 a season. He has not offered to play for less. He would not comment on any of that during the playoffs.

The ex-UCLA star did not allow even Wooden to suppress his individualism off the court. When he plays basketball, however, Walton is the consummate team player. Every coach in the NBA, including Gene Shue of Philly, would like to have a player of his caliber at center.

“The next time I take a coaching job, I’m going to have people write down what they want,” Shue says. “If they want a classic team, give me Bill Walton and I’ll give you a classic team. With him, I’m going to have leadership, intelligence, and a great fastbreak.”

“Bill Walton is the best player, best competitor, best person I have ever coached,” said Jack Ramsay, coach of the Blazers.

With one second left in the 109-107 clincher, Philly’s George McGinnis, driving to the right, pushed up a jumper, but this one bounced off the rim. After Walton leaped to knock the ball away and secure the championship, he whirled, ripped off his shirt, and heaved it in the general direction of the Blazer fans. “If I had caught the shirt, I would have eaten it,” said Lucas. “Bill’s my hero.”

“Did I plan the shirt?” Walton laughed at the question as people tried to shower his red hair and beard with champagne. “I only planned on winning.”

Then Bill asked, “Where’s my fruit juice?”

Walton, in cutoffs and a sweatshirt (and with a big lipstick print on his cheek), led the Blazers on his 10-speed bicycle as 50,000 people jammed the streets of downtown Portland the day after the victory to hail their conquering heroes. Somewhere along the route, Walton and his bicycle were parted.

He said the decision to ride the bike “may have been the stupidest thing I’ve ever done,” and asked whoever wound up with it to “please bring it back. It’s the only one I’ve got.”

Those who think of Bill as a shy, introverted, somber person wouldn’t have recognized him 24 hours after he led the Blazers to the crown. “This is as much fun as I’ve ever had in any sport since I started playing when I was eight years old,” he told 8,000 people who gathered at the Federal Plaza at the end of the parade route. “I can’t imagine it getting any better, but I’m sure you folks will find a way to make it that way.

“I now consider Oregon, rather than California, my home. I still have basically the same friends. As for my mystery man image, I’ve learned that there is a time when it’s in the team’s interest not to say anything. In some instances, not saying anything is saying a lot.

“Life isn’t a fairy tale. There’s always something you don’t want to do, but you have to do it. I’m 24 years old. This (the title) is not the end of my life. I have a long way to go . . . a lot of things to do.”

Good bye Bill Walton, we didn’t deserve you, but thanks for the Championship in ’77. And staying true to yourself.

LikeLike