[Roll over, Beethoven! “The Fabulous Fifth” mentioned here is the legendary, three-overtime Game Five thriller of the 1976 NBA Finals between Phoenix and Boston. Some still call it greatest game ever. But rather than build the case here, let’s go to the New York Times’ Sam Goldaper. He offered the following on “The Fabulous Fifth” in the 1977 paperback titled Great Moments in Pro Basketball. So, here you go. You make the call on whether it still is the GOAT.]

****

Thirteen National Basketball Association banners hang from the rafters of the old Boston Garden. Each was put there by a Boston Celtic championship, filled with sentiment and memories of great basketball moments. But as long as people compare and discuss sports, arguments will always develop over whether the fifth game of the championship series between the Boston Celtics and the Phoenix Suns, on June 4, 1976, was the best and most-exciting basketball game ever played.

The following day, newspapers throughout the nation, proclaimed the game “The Fabulous Fifth.” Some called it the greatest game ever played. But in news stories, columns, and editorials all agreed that it was a game against which all future aspirants to greatness will be measured. It was a game not only notable for extraordinarily spectacular plays, but for the amount of human frailty embodied therein.

Soon after the Celtics had beaten the Suns, 128–126, and the first triple-overtime game in the history of the NBA finals, Tom Heinsohn, the Boston coach, who stands 6-feet-7 and weighs in somewhere around the 300-pound mark, had to be assisted to the trainer’s room. Once there, he blacked out—suffering from nervous exhaustion.

Meanwhile, in the Phoenix, dressing room, Ricky Sobers, the pugnacious rookie guard, sat with his head in his hands, complaining of feeling weak and dizzy. And down the hall, in the Celtic dressing room, Paul Silas, the bedrock of the Celtics, looked wearily at his tattered sneakers and wondered out loud: “Can these go one more game? Can I?”

It took 63 minutes of playing time, spread over three hours and eight minutes of debris-throwing and name-calling, for the Celtics to take a 3-2 edge in the best-of-seven game series. Before the game was over, hundreds of young people in the capacity crowd of 15,320 at the Boston Garden tried to swarm to the players. Many in the crowd were hauled away by police for fighting with the referees, the players, the coaches, the broadcasters, the ushers, and each other.

Rick Barry of the Golden State Warriors, serving as an analyst for CBS during the series, had a soda thrown at him. A member of the crew of a local television station had to be treated for a leg injury after the game. Richie Powers, one of the officials, could not quite make it to the safety of the dressing room. As thousands stormed the court, Powers was confronted by a fan. Powers first raised his hands to defend himself, then switched to throwing punches.

Two days later, the Celtics defeated the Suns, 87–80, for their 13th championship in 20 seasons.

Never did the Celtics appear invincible. At times, their offense sputtered as they went four, five, and even eight minutes without scoring a basket. Rarely did they flash the old-style fastbreak of Celtic renown. Instead, they were a team that played well when they had to and found a new hero when they had to. What kept them alive in many games was honest defense, intelligence, and hard manual labor under the boards by Dave Cowens and Paul Silas, better known as the greatest one-two muscle duo in basketball.

Red Auerbach said of the 1976-77 Celtics, “This team had to scratch and claw for everything. Never once in these playoffs did I chew them out. You know, give them the zing like I did in other years. They did the best they could.”

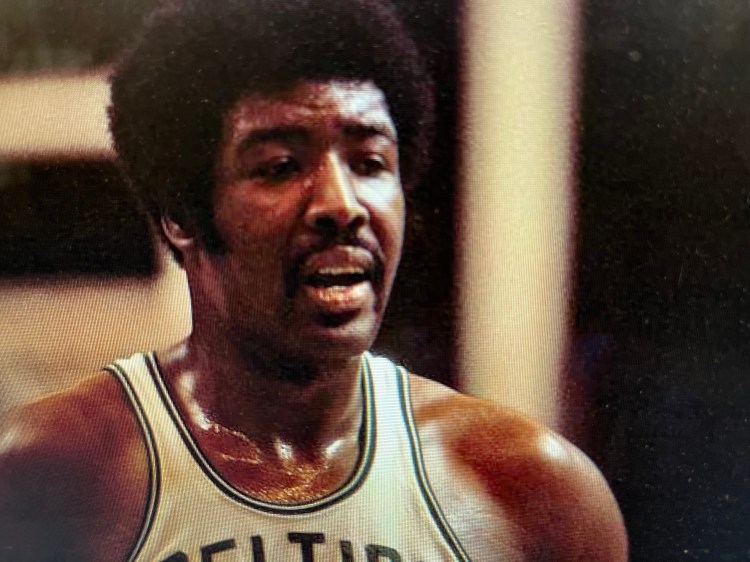

What the best amounted to was in the Celtic tradition. The names on the team changed from Bill Russell and Bob Cousy to Dave Cowens and Jo Jo White and Charlie Scott, but the character of the team remained the same.

John Havlicek once explained the Celtic tradition best when he said, “The rookies, the young players, they learn through osmosis. They look, and they absorb. They see what it is to be part of this team. It’s the long green line, and there was always someone to step in, to take over.”

In 1975, it was Scott joining the company of Dave Cowens, Jo Jo White, John Havlicek, and Paul Silas. Scott was acquired from the Phoenix Suns in a trade for Paul Westphal.

It didn’t take long for Scott to get a taste of Celtic tradition. After the Celtics’ first home game, he said, “I looked up and saw all those championship flags on the ceiling, and the feeling just captured you. It was more like college that way, with an esprit de corps. You feel like you’re part of the family.”

The Boston family, of course, makes certain demands of its players. “All they asked me to do,” said Scott, an elongated guard with quickness, tremendous speed, outstanding range, and an amazing wingspan, “is hustle every day, to play hard and hustle.”

When the 1975 Celtic training camp opened, a rookie tried to beg off doing wind sprints. “What’s the matter?” Paul Silas asked.

“I’ve got cramps,” the rookie explained.

“We’ve all got cramps,” Silas snapped back.

The rookie did his wind sprints.

Boston began slowly, but when the regular season ended on April 11 in Washington, a rejuvenated John Havlicek had scored 38 points to lead the team past the Bullets, 103-99. The Celtics had won the Atlantic Division title, even though they were never really the favorite. At the start of the season, the Buffalo Braves figured to win in the Atlantic Division, Washington was supposed to be the major playoff obstacle in the East, and the Golden State Warriors were to be the final test.

Instead, the Celtics beat out Buffalo and Philadelphia by eight games each in the Atlantic Division and then eliminated Buffalo in six somewhat easy games in the playoffs. The Celtics never had to play either Washington or Golden State. The Cleveland Cavaliers had eliminated the Bullets, and the Phoenix Suns had put out Golden State, the defending champion.

For the Phoenix Suns, it was a fairytale season. In carrying the championship series to six games, they, too, had won in a sense. The Suns, with two rookies in the starting lineup, center Alvan Adams and guard Ricky Sobers, were in last place as late as February 1. That’s when they found the missing piece to their jigsaw puzzle in the form of the power forward Gar Heard, obtained in a trade with the Buffalo Braves. From then on, the Suns played steady ball and clinched a playoff berth with some big victories in the final week of the season.

Still, the Suns finished in third place in the Pacific Division, 17 games behind the Golden State Warriors, the division champion. Never before had a team so far down in the standings reached the final round. The closest such feat was performed by the 1959 Minneapolis, Lakers, who finished 16 games behind the St. Louis Hawks and then made it to the final against the Boston Celtics.

After Phoenix had eliminated the Seattle SuperSonics, in the first round of the Western Conference playoffs, the question most people asked was, “Who were these faceless Suns?”

Since Charlie Scott had played three seasons in Phoenix before coming to Boston, he was the authority on the Suns. To the inevitable questions, Charlie would reply, “They are a great ball-moving team. They are a team of eager kids lusting for their first test of fame.”

Yet, nobody gave the Suns a chance against the Warriors in the second round. But the Suns established their credibility by winning the second game in Oakland, and from then on, it was the series. The key game was the fourth, a spectacular double-overtime triumph. But the game which changed the Suns’ image was the seventh, played in Oakland.

Tension was high for the seventh game. Everyone was waiting for the Suns to crack. Even though they were down 10 points at one point in the second period, they did just the opposite. The Suns broke open a tight game with eight-straight fourth quarter points, and then protected their lead brilliantly to nail down their first Western Conference title, 94-86. From last place in February to a conference championship in May, was a fabulous, meteoric rise.

Now the stage was set: the amazing Phoenix Suns against the awesome Boston Celtics—the new kid on the block against the all-time king of the hill.

The Celts had beaten the Suns seven straight times over a two-season span, but that was a statistic both teams ignored. Still, the Phoenix-Boston matchup figured to be the most one-sided series in the 30-year history of the NBA.

The Suns missed 62 percent of their field-goal attempts and lost, 98-97, in the opener. Then they were beaten, 105-90, in the second contest. The fans again questioned whether the Suns were just lucky to get by the Golden State Warriors, and if they really belonged in the final round.

When the Celtics arrived in Phoenix for the third and fourth games, Tommy Heinsohn, the Boston coach, analyzed the situation and said, “The Suns have got their thing going for them out here—the sun, the heat, the pools, and all that jazz. It will be a big factor against us. They may have had their backs to the wall, but they’ll be in front of that big home crowd.”

Heinsohn was correct. Paranoia power was turned on full-blast, and Phoenix won, 105-98, as Alvan Adams, the Oklahoma Kid and the Rookie of the Year, scored 33 points and pulled down 14 rebounds.

The Celtics trailed most of the way in game four—rallying to within two points eight different times in the fourth period, the last time with 13 seconds left, before losing, 109-107.

If game five did nothing else for NBA history, it accomplished two things for sure: It elevated the 30th final playoff series from gripe to greatness, and it proved that the Suns, funny suits, Thom McAn shoes, college offense, and all, belonged.

The way the Celtics attacked in the fourth quarter, the bizarre ending to the “Fabulous Fifth” was hardly expected. The Suns were down, 32–12, after nine minutes; 36–18, at the quarter; and at one point, Boston led by 22 points—its largest margin of the game. Havlicek, White, and Cowens had controlled the boards and helped in the 61-percent shooting in the first quarter. At no time during the playoffs, did the Celtics play better than in those inspired 12 minutes.

But the Suns fought back, as they have done so often in their late charge to glory. They refused to fold. Coach MacLeod had taken a diverse group of rookies and veterans—some of them castoffs—and molded a tough team. Systematically running their clockwork offense, the Suns, patiently chipped away. The Celtics, forced to shoot from the outside, scored only 34 second-half points.

The Suns trailed, 61-45, at halftime. Then they hit Boston with a 19–7 surge that cut the lead to 68–64. But the Celtics recovered quickly, and when a Havlicek jump shot made it 92-83 with 3:49 left, it appeared as though the Suns were beaten. But Paul Westphal, once the Celtics’ 1972 top draft choice, then began to express his vengeance for being traded. He scored nine of the next 11 Sun points, including a three-point play which tied the game at 94-all with 39 seconds left.

Seventeen seconds later, the Suns’ comeback seemed complete when Curtis Perry made a free-throw to put them ahead 95-94. But Alvan Adams committed his sixth personal foul, forcing him out of the game. With Havlicek at the foul line for two shots and only 19 seconds left, it appeared he was ready to ice the game for a nice, normal finish. But the Celtic captain made the first to tie the game—and missed the second.

Havlicek got the ball back again with three seconds left on the regulation clock. He shot from the corner, but the ball bounced off the rim into a Phoenix player’s hands. The Suns called timeout for one more shot, which Heard missed, to set the stage for the first of the three overtimes.

In the first five-minute overtime, each team scored six points. The Celtics went ahead, 101–97, on a baseline jumper by Jo Jo White with 1:58 remaining. But a turnaround 14-footer by Curtis Perry and a 10-foot baseline fallaway with 45 seconds left tied the score at 101-all and set up what was to be the most bizarre of the extra sessions.

Trailing 109–106 with 19 seconds to go, Dick Van Arsdale hit his only basket of the game. Westphal stole the ensuing inbounds pass from Havlicek and fed it to Perry, whose jumper put the Suns ahead, 110–109, with five seconds remaining.

Havlicek, no stranger to the task, sent the crowd into a frenzy as he made a running jumper. Everyone in the Boston Garden thought the game was over, and hundreds of young people tried to get to the players. The security police had completely lost control.

But wait! Richie Powers, one of the two officials, determined there still was one second to go. The crowd was finally persuaded to return to the sidelines, chanting, “We’re number one!”

The final second proved to be sufficient time to set up a third overtime. For openers, Westphal suggested that the Suns take a timeout—even though none remained and a technical foul would be called. His reasoning was even though the Celtics might go two points up, the Suns would get the ball at midcourt instead of under their own basket. After Jo Jo White made the technical foul that put the Celtics ahead, 112–110, Heard took an inbounds pass and made a 20-foot jumper to tie the game.

“One second is a lotta time,” Heard was later to say. “I knew I could get the shot off. Don Nelson was overplaying me because he was afraid I was going to the basket.”

MacLeod said, “Thank God for Westphal’s timeout. At the time, it saved us.”

Whereas the first two overtimes had featured incredible clutch shooting by Jo Jo White of the Celtics and Ricky Sobers, Gar Heard, and Paul Westphal for Phoenix, the third overtime belonged to Glen McDonald, the little-used sub, who came off the bench when Silas fouled out. McDonald played a superb 63 seconds, scoring two baskets and two free throws to give Boston a 126-120 advantage with 36 seconds left.

When the third overtime began, some impressive players were watching from the bench. Alvan Adams, Dave Cowens, Charlie Scott, and Paul Silas had all fouled out. Westphal tried some more heroics with two wondrous shots—a banked fallaway from 20 feet on the right side and a 360-degree spinning, right hander in the lane, but he was no match for White and McDonald. The pair combined for 12 points in the last overtime, and Jim Ard, Cowens’ understudy, hit two free throws that provided the winning points.

No one will recall that the Suns came from 22 points down in the first quarter, when it appeared the Celtics were going to blow them right back to Phoenix. What people will best remember is that the Celtics prevailed in a classic game on the night all hell broke loose in Boston. They will also remember that the Suns could have folded up and gone home.

Instead, the Suns proved they belonged.

As MacLeod fought his way through the crowd to the dressing room after the game, he said, “People thought we were a bunch of guys from the West who shouldn’t have been here. What do they think now?”

[In his 2014 autobiography Scribe, the Boston Globe’s Bob Ryan spent several pages recalling the thrill of the 1976 NBA Finals. That, of course, includes a special swoon for game five. He wrote: “The game featured so much athletic splendor, so much craziness, and so many timely plays made by so many different people. It would have been a very good NBA Finals game had it ended with the Celtics winning in regulation. But the events of the final seconds of the fourth quarter and the ensuing three overtimes transformed this very good game into a true NBA epic.”

Below is a younger Ryan in his own, “I can’t believe what I just saw” words written right after “The Fabulous Fifth.” Rarely, does a hometown reporter heap praise on both teams, but this is one of those awed instances.]

What do you say after you’ve seen the greatest game of professional basketball ever played? That there should’ve been two winners? That it should’ve been a bargain at $250 courtside? That no matter what happens in the final two games of the 1976 playoffs, two teams with heart are competing in the finals? Perhaps rarely in the history of any professional sport have so many incredible clutch plays been turned in during one game by so many people?

Yup, yup, yup, and no doubt about it. A delirious mob of 15,320 fortunate patrons stayed at the Garden past midnight last evening to see the Celtics grab a 3-2 series advantage by virtue of a dramatic 128-126 triple overtime victory over the valiant Phoenix Suns.

So much happened in the final 19 minutes of this memorable affair that the scintillating first half (in which the Celtics built up a 22-point lead, had it chopped to seven, and then mounted it back again to 16 at the half) seemed as if it had been played back on Easter Sunday.

By the time the team got around to settling the outcome, Dave Cowens, Charlie Scott, Paul Silas, Alvan Adams, and Dennis Awtrey had all fouled out, and the game was being decided by the most-improbable playoff hero since Gene Guarillia—Glenn McDonald.

It was McDonald, sent into the game when Silas fouled out at 3:23 of the third overtime, who came up with a minute and three seconds of big plays that he and all the Celtic fans will long remember. His little spurts began with the score tied at 118, that deadlock having been provided by the next-to-last in an incredible string of Sam Jonesian baskets by Jo Jo White, who crammed 15 of his game-high 33 points into the three overtime periods.

At 118-all, Jim Ard (another big hero) won a jump ball from Curtis Perry at the Suns’ foul line. That turned into a Boston fastbreak on which McDonald deftly converted a pretty pass from White. Gar Heard—more on his astounding heroics later—missed a jumper, and Don Nelson rebounded. On this transition, John Havlicek spotted McDonald on a crossover along the left baseline and hit him with a crisp pass. McDonald hit a quick turnaround to make it 122-118.

Paul Westphal (an amazing fallaway) and White matched baskets, before Dick Van Arsdale missed—the Suns were tiring, at long last—and McDonald soared for the rebound. Curtis Perry (another hero in defeat) fouled him in the backcourt, and McDonald calmly tossed in two free throws to give Boston a 126-120 advantage with 36 second remaining.

But these were the Phoenix Suns, a team which is becoming synonymous with adjectives such as gutsy, spunky, gritty, and classy. The game was far from over, even when Ard, fouled intentionally off the ball, made two foul shots with 31 seconds left.

Those Ard foul shots were sandwiched between a pair of Phoenix baskets, a layup by Ricky Sobers—he’s a rookie—and a driving, 360-degree banked spinner by Westphal. When McDonald lost the ball underneath the Boston basket, Westphal wound up with a sneak-away layup to close the gap to 128-126 with 12 seconds to play.

Again, the Suns threatened when Westphal actually got his fingertips on a looping pass intended for Ard. But Ard kept possession, and the Celtics were finally able to run out the clock, even as Heard and Van Arsdale were vainly trying to foul away from the ball in the hopes of regaining possession.

But if the ending was a battle of punched-out heavyweights, what set it up was worthy of Graziano-Zale at their peak. Take, for example, the second overtime, the final 19 seconds of which included: a White drive to give Boston a 109-106 lead; a Van Arsdale 18-footer four seconds later; an immediate Westphal steal from Havlicek on the inbounds pass; a Perry third try swisher from 15 feet to give the Suns their third lead of the entire ballgame; a Havlicek leaning banker with two seconds to play to give the Celtics and their fans what they thought was a 111-110 triumph; a crowd celebration on the court; a declaration by the officials that the Suns would still get a second to play; a technical foul on Phoenix for calling a timeout they didn’t have in order to get the ball at midcourt; a White conversion of the technical to make it 112-110; and, finally, a perfect toss into the basket with no time remaining by Heard to send it into the third overtime.

Somewhere back around the start of the 6 o’clock news, the Celtics had come blasting out of the locker room to annihilate Phoenix with great shooting (8-for-11 to start the game) and defense to move ahead by scores of 32-12 and 34-14.

The resilient, patient Suns were unmoved by the experience: they fought doggedly and implemented an increasingly sticky defense to pull within 16 (61-45) at the half and within five (77-72) after three quarters. Seemingly dead, while trailing, 92–83 with 3:49 left, they rallied behind Westphal to go ahead, 95-94, on a Perry free throw, which Havlicek matched with 19 seconds to play in regulation.

Towering figures abounded on both sides, but The Man with all the money on the table was White, who established his backcourt preeminence in the series with a great show. But any number of people could ask for a bow. To have seen this masterpiece was a privilege, and nothing less.

[On June 14, 1993, the Arizona Republic ran retrospective on The Fabulous Fifth with this timely interview with Gar Heard about The Shot Heard ‘Round the World. The bylines belong to Bob McManaman and Pat Underwood. For the sake of continuity and clarity, I’ve edited out references to the 1992-93 NBA season.]

The date was June 4, 1976, the place Boston Garden. The Phoenix Suns and Boston Celtics were in Game 5 of the best-of-seven NBA Finals, the first time Phoenix had made it to the championship round since the team’s inaugural 1968-69 season.

After eliminating the Seattle SuperSonics and upsetting the world-champion Golden State Warriors in the Western Conference finals, the Suns were tied at two games apiece, up against the likes of rugged Celtics center Dave Cowens, tenacious forward John Havlicek, and hot-shooting guard Jo Jo White.

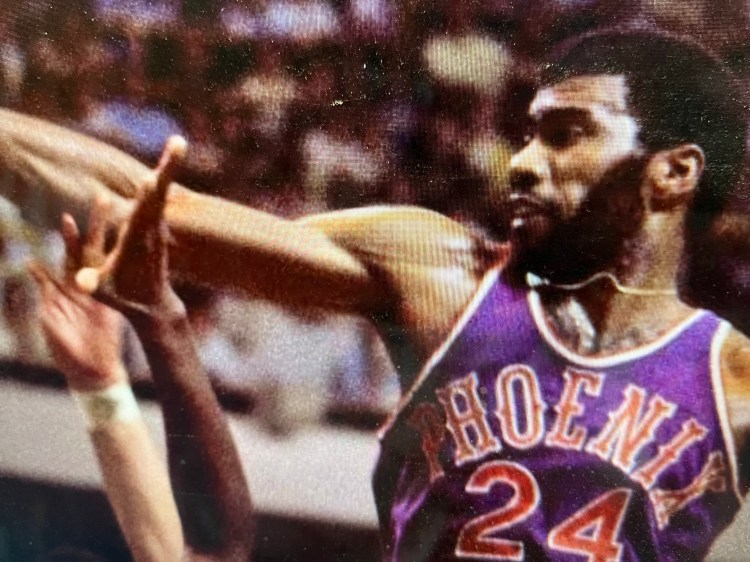

That the Suns knew. What they didn’t know was that they were to make NBA history that day . . . and it was an unlikely hero who forced Game 5 into triple overtime. Garfield Heard, a Suns forward with an inconsistent outside shot, made a 20-foot rainbow jumper from above the circle that was to become known as “The Shot Heard ‘Round the World.”

And it was made in the final, frantic second of second overtime in what’s been called The Greatest Game Ever Played. That the Suns lost Game 5, 128-126, or fell in the Finals, four games to two, didn’t diminish the Suns’ effort that day or Heard’s dramatics.

There’s still disagreement over whether Heard was supposed to get the shot on a designed play. But not if you listen to Heard.

“Forget what everybody else says about it,” Heard said, laughing. “Let me tell you how the play was called.

“There was only one second left on the clock. It was supposed to have been a lob pass from Curtis (Perry) to the basket, and I was supposed to try and go in and get the pass and tip it in.

”That,” Heard explained, “was the designed play, although I’ve heard about 15 other plays since then.”

Heard remembers the play like it happened yesterday. But that’s probably because he is asked about it all the time. “Don Nelson was playing me, and he wouldn’t never let me go back door,” Heard said. “For some reason, he played behind me, and Curtis just threw the ball directly into me. I just turned and shot.

“So, it was designed for a lob, but after we couldn’t get the lob, we just kind of improvised a little bit, and it worked out.”

It was a shot that thousands of young Suns fans that year kept reliving on Arizona’s playgrounds and schoolyards. It is safe to say that none of their shots was as perfect as Heard’s was at Boston Garden.

And he wouldn’t have gotten it had it not been for a baseline jumper from Dick Van Arsdale with 15 seconds left in the second overtime. Or if Paul Westphal hadn’t swiped the ensuing, inbounds pass, which resulted in a Perry jumper and a one-point lead for the Suns with five seconds to go.

Havlicek’s leaning jumper in the lane with time running out gave the lead back to Boston. Fans rushed the court, thinking the game was over. But it wasn’t. When the bedlam subsided, Westphal shrewdly called timeout. The Suns were out of timeouts, which Westphal knew would cost them a technical, but it paid off.

Boston made the free throw for a 112–110 lead, but the technical meant Phoenix would get the ball at midcourt instead of under the Celtics’ basket. After the officials put one second back on the clock, the stage was set for Heard. Here’s how Al McCoy, the longtime voice of the Suns, called the play:

One second remaining in the second overtime. Here’s Perry. To Gar Heard. Here’s the jump shot . . . GOOD! IT’S GOOD! IT COUNTS! GAR HEARD TIES IT. We’ll go to the third overtime! I’v got to take a breather. Garfield Heard made the basket. I want to tell you something, somebody up there is on our side!

Heard said he wonders to this day if divine intervention had anything to do with his high-arching shot swishing through the net. “You know, when it went in, I really felt something,” he said. “I don’t know what it was. But I felt something.

“Then again, right after that, I thought we were really going to win the game, too.”