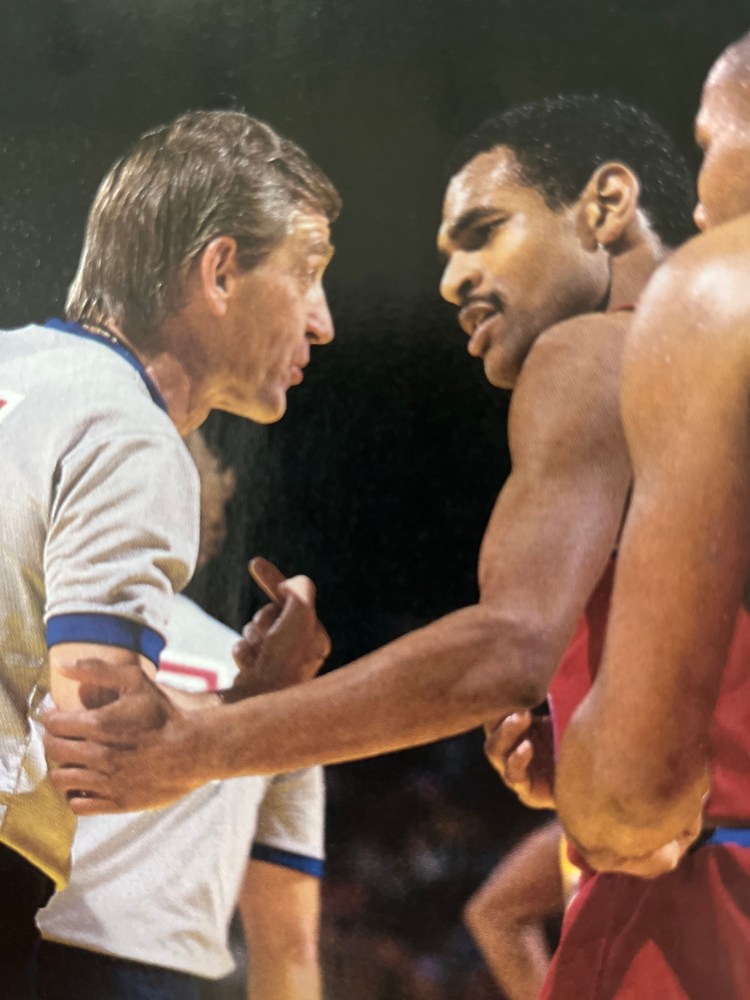

[Maurice Cheeks always has been a class act. Not bad for this once-shy kid who sang Happy Birthday in rookie camp. Cheeks also was one of the best true point guards of the 1980s, as many of us vividly remember. In this article, pulled from the April 1988 issue of Hoop Magazine, the Philadelphia Daily News’ excellent reporter/columnist Phil Jasner takes a look at Cheeks during his 10th NBA season and playing alongside the young Charles Barkley. Cheeks would spend 15 years in the association, retiring at age 36. Now age 66, Cheeks is an as assistant coach with the Chicago Bulls and a deserved Hall of Famer, class of 2018. ]

****

It is the spring of 1978, and the Philadelphia 76ers, without a first-round pick in the upcoming draft, are scanning the country for an appropriate guard to take in the second round. They have some interest in Tommy Green from Southern and Jeff Judkins from Utah. And a kid from a bad, walk-it-up West Texas State team. Maurice Cheeks.

They invite the three to a specially convened camp in Cincinnati put together by attorney Ron Grinker. It is a laboratory experiment for the benefit of general manager Pat Williams, coach Billy Cunningham, and super scout Jack McMahon.

It is the beginning of a relationship. “Because of the playoffs, Jack hadn’t been able to come to the camp I have every year, but he called one day and said, ‘Listen, can you have your camp again?’” recalled Grinker.

“Again?” He explained that they wanted to look at some guards, and they gave me a list. I filled in with kids in the area, so we could have scrimmages. It was no secret that Jack liked Green and Cheeks, and when the camp was over, I asked which one he’d go for. He said I’d find out.”

New Orleans snapped up Green. Boston reached for Judkins. Cheeks fell to the Sixers.

“I asked Jack then—I ask him now—and he says it was Cheeks all the way,” Grinker said. “Then he always smiles and says, ‘But you’ll never know!’”

“I say that,” said McMahon, now with the Golden State Warriors, “but, really, it was a no-brainer. If we had a first-round pick that year, we’d have taken Maurice there, too.”

It is 10 years later. Nine full seasons. Four all-star games. Three visits to the Finals. A championship. Four berths on the All-Defensive Team.

Maurice Cheeks, at 30, is suddenly the oldest Sixer, even if he does not feel it. He is a leader, even if he does not want to be one. He is a spokesman, even though he usually prefers to say little. “It’s all gone quickly and slowly at the same time,” he was saying. “What’s interesting is, I can remember everything that has happened in the 10 years. Even the restaurant at training camp (in Lancaster, PA)—where I had to get up and sing as a rookie—has been redone. Now the rookies ask when they should sing!”

The rookies this year unfurled a terrific rap, wearing dark glasses and turned-around baseball caps, stunning the veterans with their ingenuity and clever lines. “Me? I sang ‘Happy Birthday,’” Cheeks recalled.

“I didn’t say a word to anybody that whole camp, unless somebody said something to me. Even then, I didn’t say much. And I said it almost in a whisper. I sang my song; it was probably the only time anybody heard me. They gave me the thumbs up, I sat down. I think it was because I’ve been so quiet, hardly anybody knew I was there.”

He wouldn’t mind if a reporter never approached him with a pad and pencil, if a cameraman and producer never asked him to do a TV spot. He might be the only player out there who doesn’t want to be a TV analyst after he retires.

“This is all so different now,” Cheeks was saying. “I’m the older player here, as opposed to when I was trying to make the team. I see the kids following us, looking around, observant, as opposed to me doing the following.

“I came to my first camp, it wasn’t that I was skeptical of my talent, it just wasn’t something I thought much about. I just went out each day and played, hoped the results would take care of themselves. I had been surprised to have been drafted that high. At one point, I was surprised to have been drafted at all. I had even focused on not making it, so that when I got cut, I wouldn’t be devastated.”

Cut?

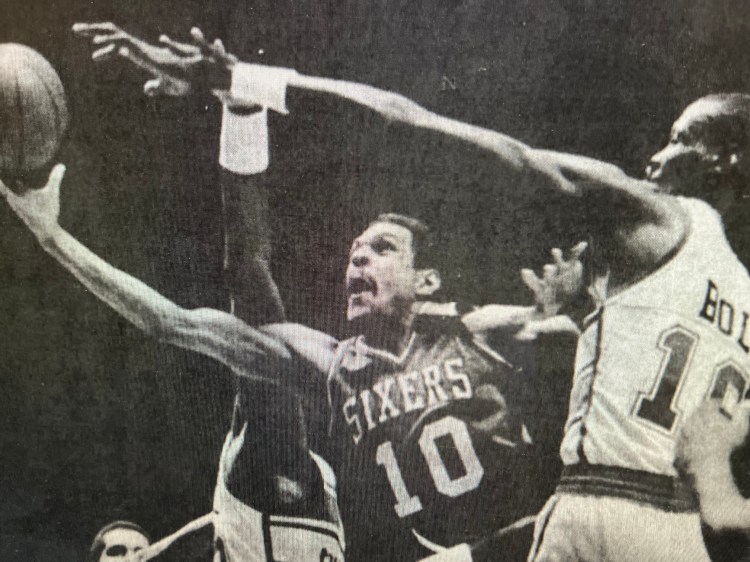

Maurice Cheeks has become the game’s best, most-consistent pure point guard. That’s disregarding the Los Angeles Lakers’ Earvin “Magic” Johnson, because point guards aren’t supposed to be 6-feet-9 and capable of leading a team in rebounding. That’s disregarding Detroit’s Isiah Thomas, because he’s at once so dominant offensively yet frequently error-prone.

There are other fine ones. Houston’s Eric “Sleepy” Floyd. Utah’s John Stockton and Rickey Green. Seattle’s Nate McMillan. Milwaukee’s John Lucas. Portland’s Terry Porter. New York’s rookie Mark Jackson.

But the best is in Philadelphia. Right now. “Without flare or flash,” says Sixers’ assistant coach Fred Carter. “Simplicity is his game. He doesn’t appear to be disrupting an opponent’s defense, yet he gets 15-to-17 points every night. When he plays defense, he sets you up, then gets his steals off the set-ups.

“His reputation was always as an underrated player, but never among the other players or the coaches. The key is his dedication, and dedication in any field is a beginning. God gives you the level of skills, but you need to do the work to bring them out.

“It’s easy to say there are no perfect players, yet at his position, what he gets done, he’s a perfect player. Point guards come into the league every year. He sees them come; he sees them go. They swagger out, he shoots them down.

“No oohs and ahhs. No rave reviews. No curtain calls. But he’s the one to emulate. Hey, everybody can’t sing like Springsteen, but we can all get into the shower and try.”

“The way he plays defense is an insight into his personality,” suggested Sixers assistant coach Jim Lynam. “You pressure the ball 35-40 times a night, it’s a thankless job, you usually have to prod that out of players. It’s not something that’s going to draw a reaction from the fans.

“And he’s there every night. A lot of guys come close to every night, but he doesn’t miss any. Break down his game, and he doesn’t have many weaknesses, A to Z. What sometimes gets missed is his ability to spot-up shoot. I don’t like to use cliches, but in that category, he’s flat-out great.”

Eras change.

Sometimes painfully.

Maurice Cheeks once said he couldn’t imagine the Sixers without Moses Malone. Pretty soon, Malone was gone, traded to Washington.

Cheeks said he couldn’t see a Sixers team without Julius Erving. When last season ended, Erving retired.

His comrades were going, going, gone. Andrew Toney was struggling with foot problems. Clint Richardson and Clemon Johnson were traded. Bobby Jones retired. Even Billy Cunningham, his coach, his authority figure, left.

”I know it was inevitable, but it was rough last year. It’s rough right now,” Cheeks said. “I used to come out on the court and see Doc (Erving), Moses, a healthy Andrew. Bobby and Clint would be right behind us. I always knew I had a chance to win. Not just win a game, but win all the time, win it all.

“To go out there now, knowing I’m the oldest, that those guys aren’t here . . . Sometimes I think: ‘What happened? Why aren’t they here?’ But I know why. I felt that way last year, even though Doc was still here. I knew this was coming.”

They went to the Finals in 1980 and 1982, brought in Malone and won the title in 1983. They haven’t been past the second round since.

“I’m biased toward Moses, always will be,” Cheeks said. “I knew if we needed a field goal, I could give it to Moses, he’d get a bucket, get a foul, get a rebound. I can do that with Charles (Barkley) now, but Moses had been through the trenches, year in, year out.”

They miss the Doctor, too, in ways they don’t understand or won’t acknowledge. But Cheeks understands. Cheeks knows. “I miss him on the court, in the locker room, on the road, off the court,” he said. “When something needed to be said, he’d say it more diplomatically than Charles might say it. On the bus, he’d always be the last one on, but he waited. We knew he was coming.

“I always thought the young guys should have appreciated him, observed him, learned from him . . . But kids coming in now are more confident than I was. I don’t know if that’s the quality of the individuals, how people are brought up nowadays, the type of schools they come from, or what. David (Wingate) comes in, you can see where he’s been. He has a toughness that comes with being at Georgetown, winning the NCAA tournament. He knows he can play.

“They had ceremonies in every city for Doc. I hope the young guys (around the league) appreciated it. They may never get a tour like that, but they don’t always think that way. They think they’re so good (already), they have different minds. Some are spoiled before they even get to the pros.

Cheeks, reluctantly, is sharing the captaincy with Barkley. “I’ll do what I’ve done for nine seasons. I won’t deviate,” he said. “I’ve been leading without saying much, but that’s me. Charles is more energetic; he’ll lead us his way. He’ll take the scoring load, the rebounding load, he’ll be out front. It’s funny, I never thought about being a captain. It was always Doc’s job.”

The young Maurice Cheeks needed reassurance, support. He got it from Billy Cunningham. “People say I’m the best, and it’s nice to hear, but I know things change overnight,” Cheeks said. “I don’t get caught up in it.

“One year, I got off slowly, Billy took me aside, said I had worked too hard to let it slip away. It made me think. I hadn’t tried to play bad; it just wasn’t happening for me. But I played harder, harder than I thought I could.”

“His rookie year, we lost to San Antonio in the playoffs,” Cunningham said. “He took the last shot, it didn’t go; he’s so dejected. I told him I was ecstatic for him. I said anybody could have missed the shot, but not everybody would have taken it.

“Another time, I told him he had to improve his leadership, be more an extension of the coach. He went home to Chicago that summer and played on the youngest team in the summer league so he’d have to lead.

“During the 1984 playoffs, we were in the first round against New Jersey. He had taken a terrible fall, had a bad knee, a cut above his eye. I asked him how he felt. He said his knee was fine, his eye was fine, but he couldn’t straighten his back. He played 48 minutes.”

“There’s usually a syndrome of a point guard turning 30, slowing down, showing a dropoff,” said Sixers owner Harold Katz. “But Maurice had a great year. I looked for telltale signs, didn’t see any. I saw what I always saw. I love to watch him.

“I remember him as a rookie, before I bought the team. That year, he went from being a good rookie to a mature player that fast.”

Last year, Katz gave Cheeks a new four-year contract believed to be worth $4 million. “I sometimes feel guaranteed contracts are dangerous for older players,” Katz said. “My concern was Maurice would be 34 at the end, and most fade at 32. But I watch him now. I don’t see that happening.”

No, Cheeks hasn’t changed. He’s still pressuring the opposing point guard, picking him up at three-quarter court 30-to-40 times a game, looking for the two or three steals that might make the difference, creating the disruption that might warp an opponent’s gameplan.

“I don’t count the times I (apply) pressure, it’s just something I do instinctively,” he said. “I want the opponent to be thinking, to be concerned about the next time, the next game, make him remember he has to get ready to play against me.

“I’m a confident player today, and that comes from Billy, too. He trusted me, believed I could play when I didn’t believe in myself. It took a lot of guts on his part.”

“Sometimes a big reason for success is circumstance,” McMahon said. “That was a time when we had a bunch of crazies, and I’ve always believed that Maurice’s coachability kept Billy in coaching as long as he stayed. Other guys, you couldn’t tell anything. Maurice, you could tell him something and see the results.”

McMahon recalled gathering his initial clues watching Cheeks play for West Texas State. “Not a good team, and no one was allowed to shoot past 15 feet,” McMahon said. “To be involved in the offense, Maurice had to take it to the hoop. I saw speed in him, and, anyway, I never liked stand-around shooters.”

Ten years later, Cheeks does not know what he will do with his life after the cheering stops, but he says it will not be a major adjustment. “It won’t have to be,” he said, remaining perfectly in character, “because I try not to listen to the cheering now. If I don’t listen now, I won’t miss it later.”