[It was one of the strangest trades in NBA history. No, not Wilt for Lee Shaffer, Connie Dierking, Paul Neumann in 1965. I’m referring to the ownership swap of the Boston Celtics and the Buffalo Braves in 1978. Here’s a real quick summary of events from former Buffalo Brave Randy Smith:

Once John Y. Brown got his hands on the team, Buffalo was the last place he wanted to have it play. He and I used to talk a lot. He’d tell me about the possibility of the team going to Dallas, San Diego, Kentucky—it was inevitable the team was going to leave the Buffalo area. Then I woke up one morning and he had made the team swap. I was home in Buffalo. Somebody called me from the Braves’ office to tell me the news. John Y. had swapped teams with Irv Levin, and Irv Levin was going to take the team out to San Diego . . .

I started to get checks from the Boston Celtics for deferred payments. I didn’t know where to expect my checks to come from back then, but you don’t care as long as they didn’t bounce. That’s what happens when things get as crazy as they did at the end of that season. You just hope the checks don’t bounce.

The story that follows from the old-reliable New York Times reporter Sam Goldaper dives into the craziness a bit. But it’s really about the old Celtic stalwarts getting rid John Y. and reclaiming their championship ways with the new kid named Bird and youngsters Robert Parish and Kevin McHale en route. The rest is the stuff of NBA legend. Goldaper’s story ran in the magazine Basketball Special, 1980-81.]

****

It was late March, and the regular National Basketball Association season was nearing an end. Some 10 days later, the Boston Celtics would finish the 1979-80 season with a 61-21 won-lost record, the best in the league, and accomplish the biggest single-season turnaround in NBA history. The season before, the once-proud Celtics, who have won 13 titles, had posted a 29-53 mark, their worst finish since the 1949-50 season when they won 22 and lost 46.

“It was basically a terrible year, a waste,” was the way Don Chaney, the Celtic co-captain, was later to describe the 1978-79 season. “We were in constant turmoil, and the front-office interference was unbelievable.

“Players came and went, and you can’t play basketball or win with so many changes. That season, we had something like 30 different guys in and out of Celtic uniforms. I don’t think the owners should have anything to do with the players. That’s why there are coaches and general managers.”

Chaney’s criticisms were directed at John Y. Brown and Irv Levin, who in July 1978 had staged one of the most unusual sports trades ever when they swapped ownerships of their respective franchises. In the deal, which also included seven players changing uniforms, Brown and Harry Mangurian, the owners of the Buffalo Braves, took over control of the Celtics. Levin, the Boston owner, who lives in California, became the owner of the Buffalo Braves. Levin’s next move was to relocate the Braves closer to his home, and the San Diego Clippers were born.

The ownership change was the Celtics’ eighth since Walter Brown, the team’s founder, died in 1964. Levin had become a half-owner of the Celtics with Robert Schmertz in 1975 and became the club’s sole owner after Schmertz’s death the following year.

Brown, currently the governor of Kentucky, had purchased the Buffalo franchise in early 1977 from Paul Snyder, the team’s original owner, and then sold a half-interest to Mangurian. The two have completely different personalities in their basketball ways and dealings. While Mangurian, the Florida businessman, prefers to stay out of the limelight, Brown has always craved the spotlight, dating back to the days when he owned the ABA’s Kentucky Colonels.

Brown was a strong believer that he could make things better. He was never satisfied with things as they were and often acted on impulse. Nowhere was his attitude more apparent than in his impulsive trading of players. In those half-dozen years of his involvement with the Colonels, Braves, and Celtics, he engineered more than 50 deals, including some of the bigger names in the sport.

Brown’s acquisition of the NBA‘s most-celebrated franchise was viewed from the start as a damnable irony. His meddlesome ways were strange to Chaney, who spent nine of his 11 pro seasons in the Celtic backcourt, and even stranger to Red Auerbach, the Celtics’ legendary president, general manager, and former coach, who has led Boston to nine championships in 16 seasons.

The Celtics storyline is familiar. A benevolent owner named Walter Brown hired a gruffy coach named Auerbach for the 1950-51 season. Auerbach took a ragtag, financially depressed team and built it into the pride of pro basketball. From 1957 to 1969, the Celtics won 11 NBA championships in 13 seasons, a feat unmatched in professional sports history. When the Celtic old guard was finally ushered out in the persons of Bill Russell, Sam Jones, K.C. Jones, and Tom Heinsohn, there was nothing left for the 1969-70 season.

But Dave Cowens arrived to play center the following season, and a new era began. That era yielded two more championships before things began to fall apart in 1977 under Levin’s ownership and the following season with Brown in control of the club.

During the 1977 and 1978 seasons, when the Celtics won 61 and lost 103, they lacked the Auerbach chemistry that had always blended the right players, acquired with the right owners, and handled in a proper manner by the right coach. Those ingredients were missing during those two seasons.

From May 1, 1966 to May 23, 1975, the Celtics went without making a body-for-body trade. However, by the time the 1978-79 season was 17 games old, Cedric Maxwell, the Celtics’ 1977 top draft choice, was third on the team in continuous service.

All previous Celtic ownership changes went smoothly and always left Auerbach in complete control. In John Y. Brown, Auerbach had acquired an owner of a different stripe. Brown had come from the ABA, a league scorned in the pre-merger era by Auerbach. More importantly, Brown, in word and deed, immediately declared himself an active owner who would be involved in the details of the club’s operation, something new to Auerbach.

But what really got Brown and Auerbach off on the wrong foot was a controversial seven-player trade that had accompanied the franchise shifts. Neither Brown nor Levin had consulted with Auerbach about the trade in which the Celtics gave up Kermit Washington, Freeman Williams, Sidney Wicks, and Kevin Kunnert for Nate Archibald, Marvin Barnes, and Billy Knight.

The immediate question was whether Auerbach and Brown could work harmoniously together, since they were both set in their ways. “I have had a lot of owners in the 12 years,” said Auerbach in response to his ability to work with Brown, “and some didn’t know the difference between a basketball and a hockey puck. I got along with them.

“Sure, I’ve got my own personality and my own feelings, and sometimes I like to have my own way. But usually, I think it’s only fair to discuss situations with the guy who owns the ballclub. It’s his money, he’s entitled to know. I don’t have an ego that I want to do it all myself.”

Auerbach was hardly without options when Brown arrived. Sonny Werblin, the president of Madison Square Garden Corporation, which owns the Knicks, offered him the presidency of the team. Only Auerbach’s long Celtic association kept him from moving to New York.

Auerbach tried working with Brown, but became even more enraged when John Y., without his knowledge, traded the Celtics’ three first-round draft choices to the Knicks on February 14, 1979 for Bob McAdoo.

The McAdoo trade again almost sent Auerbach to the Knicks. It was only after Mangurian purchased full control of the Celtics before the start of last season that kept Auerbach in Boston. Mangurian was smart enough to put Auerbach back in full control, and the Celtic turnaround followed.

Auerbach and Mangurian have hit it off perfectly. “Not a single disagreement,” says Auerbach.

“That’s because Red has gotten his way on everything,” added Mangurian with a smile.

And that, it now seems, is what the Celtics needed. The new atmosphere—almost one of athletic resurrection—was evident in everything the Celtics did since Auerbach regained control. “The losers are gone from this locker room,” said Chaney of the turnaround. “Now the feeling is back.”

That very night in March as Auerbach sat in his office, he hardly knew where to begin discussing the Celtic turnaround. Was Auerbach’s best move the hiring of Bill Fitch as the Celtic coach? Or was Auerbach’s most-inspired action his gamble to draft Larry Bird in the 1979 draft as a junior eligible and then weather months of negotiations before Bird finally signed his $650,000 a year contract.

Maybe Auerbach’s biggest coup was sweet-talking M. L. Carr, a Detroit Piston free agent, into a Celtic uniform and then settling the compensation issue by giving up McAdoo and receiving the Pistons’ No. 1 choice in the 1980 college draft. That pick, which the Celtics traded to the Golden State Warriors for the 7-foot Robert Parish, turned out to be the No. 1 selection in the entire draft.

The Celtic new—Fitch, Bird, and Carr—blended well with the Celtic old—Dave Cowens and Nate Archibald.

Fitch was the first Celtic coach since Auerbach who wasn’t a former Celtic player. “After Bill Russell, Tommy Heinsohn, Satch Sanders, and Dave Cowens,” said Auerbach, “we just ran out of former Celtic players as coaches. We went outside the family, and it was the best decision I ever made. No matter how successful you are, you have to have the flexibility to make changes when they come up.

“A year ago, when I would walk to my seat in the Boston Garden, I would hear the fans accuse me of butchering the team. Now that we’re winning, everyone is telling me that I went from a genius to a dunce to a genius.”

Fitch coached the Cleveland Cavaliers for nine seasons before coming to Boston. During the 1970-71 season, the Cavaliers became a member of the NBA and, simultaneously, a national joke. After losing their first 15 games, a newspaper sponsored a contest in which it asked readers to predict the first victory. The prize was two tickets to a Knick-Cavalier game at Madison Square Garden.

Cleveland’s first success came on November 10, 1970 against the Buffalo Braves. The Cavaliers then went off on another losing streak during which Fitch said, “Sometimes you wake up in the morning and wish your parents had never met.”

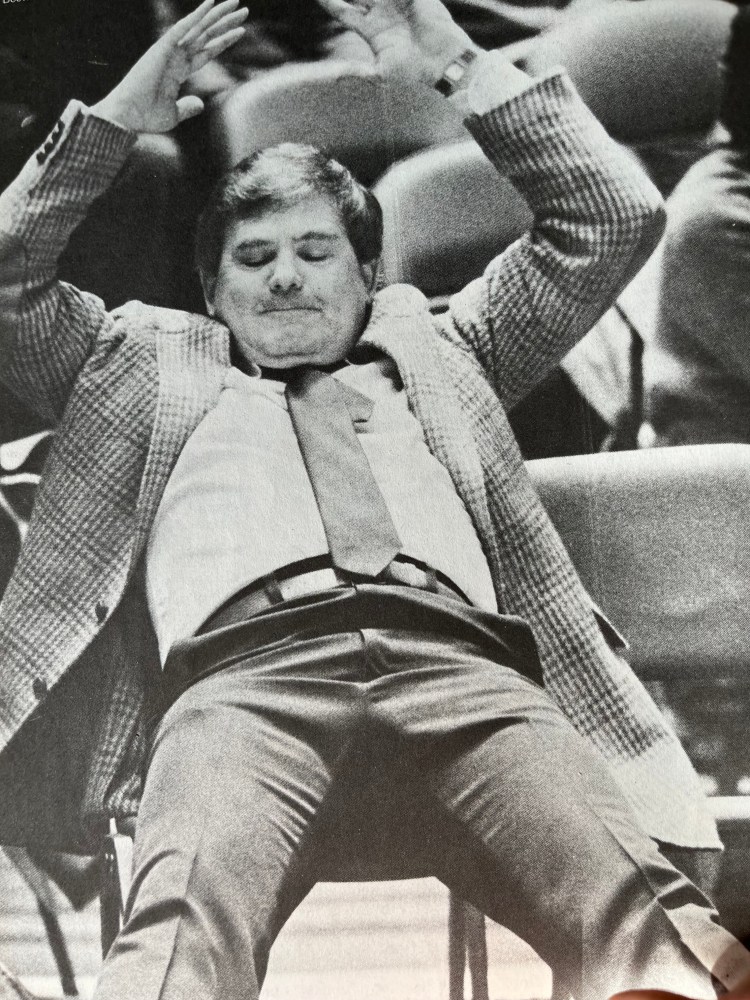

As the Cavaliers became the lovable losers, winning a total of 35 games in their initial season, Fitch became the NBA’s funnyman. Once, when his team came close to winning a game, Fitch quipped, “Close only counts in horseshoes, hand grenades, and drive-in movies.”

With the pressures of reviving the Celtics mounting, Fitch forgot about the joke routine and instead put the Celtics through a grueling training camp and unmercifully rode those he thought were not going all out. All season long, he demanded two hours of non-stop exertion from his players during the practices, and more often than not, he did not reward them with words of kindness.

“It hasn’t been as much fun as you might think,” said Fitch as his team headed into the playoffs. “The pressures have been incredible. You just can’t relax. It’s like playing a record at the wrong speed; it doesn’t sound pretty.”

Auerbach made one of his shrewdest moves when he drafted Bird after his junior year at Indiana State. Right from the start, Bird proved he was worth every cent that he bickered for. He helped bring the fans back to the Boston Garden.

The importance of Bird’s contribution to the Celtic turnaround cannot be understated. In winning Rookie of the Year honors, the 6-feet-9 Bird, in 82 games during the regular season, averaged 21.3 points, 10 rebounds, four assists, and helped make everyone else on the court a better player. In Celtic tradition, Bird threw blind passes the way Bob Cousy did. Additionally, he proved to be an awesome shooter and a better rebounder than anyone had thought.

In Celtic tradition, Carr, a small forward occasionally shifting to the backcourt, became the all-important sixth man, a vital aspect in Celtic winning tradition. The 6-feet-6 Carr, who could play defense and pick people up, was quick to understand the Celtic way better than most.

“Celtic pride is not a myth, it’s for real,” said Carr. “You don’t have a lot of petty junk here and, in the NBA, that’s the exception, not the norm. This isn’t a team with overpowering talent, but it’s a team that won’t die. Guys are concerned with the situation and have a common goal—to win games for the Boston Celtics.

“This team will be America’s team. We got nothing but All-American guys. Nobody does anything bad. We break curfew the wrong way. We go to bed an hour before we were supposed to instead of an hour after. Everybody here has a role and, in the pros, this is what it’s all about. I came to the Celtics as a player and as a fan. A lot of people would give anything to be in my situation.”

Cowens was equally as happy as Auerbach when Brown sold out to Mangurian. The 6-feet-9 Cowens had never been a fan of Brown, nor of McAdoo, whom Brown forced on Cowens in the Knicks trade.

Cowens became the player-coach in November 1978, replacing Satch Sanders after the Celtics had won only two of their first 14 games. Boston had a 27-41 won-lost record under Cowens, and the total of 53 losses was the most in one season by any Celtic team. With both jobs too much for him, Cowens resigned as the coach at the end of the season to concentrate on being Cowens, one of the best centers in the NBA for 10 seasons.

Cowens was born again when Fitch took over the coaching reigns. He came to training camp in better shape than anyone else and provided the leadership in words and by deed.

At age 31, Cowens no longer had the unique leaping ability he showed during his younger days in the NBA. In addition to averaging 14.2 points a game and hauling in 947 rebounds, Cowens remains the best defensive center in the league. “Dave is our quarterback,” said K.C. Jones, the Celtics assistant coach, “and that is what a center is supposed to be on defense. He’s not a shot blocker like Russell, but other than that, he’s the best.”

Archibald, like Cowens, was born again under Fitch. The 1978-89 season had been a dismal one for the 6-feet-1 Archibald as his scoring average tailed off to 11 points a game, the lowest since he came into the league with the Cincinnati Royals for the 1970-71 season. He missed the entire 1977-78 season while playing for the Buffalo Braves, and the effects of his leg injuries were still evident.

It was different last season, as Archibald showed sparks of the form that earned him three earlier all-star berths. He was second in the league with an average of 8.4 assists a game. When the Celtic offense slowed down, Archibald was expected to penetrate—and usually did. His rubber-band drives became a legend around the Boston Garden.

After a first-round playoff bye, the Celtics overwhelmed and eliminated the Houston Rockets in four straight games and advanced to the Eastern Conference final against the Philadelphia 76ers, a team they had battled for first place in the Atlantic Division during the regular season.

The Celtics went into the series as the favorite, but were quickly eliminated in five games. For the first time all season, several of the Celtic weaknesses surfaced, especially Darryl Dawkins’ ability to dominate the older Cowens. “All season long our strengths were our quickness and outside shooting,” said Fitch in appraising his team’s quick elimination. “The 76ers took those parts away from us. We beat them three times during the regular season when we shot 50 percent from the outside. If you don’t shoot the basket outside, you won’t beat Philly inside. They were awesome inside defensively. That was especially evident in the fourth game when we tried to go inside, and they blocked 15 shots against us.”

The Celtics hopefully rectified some of their inside weaknesses during the offseason. Instead of using the first pick in the draft to select the 7-feet-1 Joe Barry Carroll of Purdue, the Celtics traded their No. 1 and No. 13 picks to the Warriors for Parish and the third choice in the draft. In Parish, the top selection in the 1976 draft, the Celtics got a young, established center to spell Cowens. Parish averaged 17 points, 10.9 rebounds, 1.6 blocked shots last season. Boston used the No. 3 pick for the 6-feet-11 Kevin McHale of Minnesota, an outstanding power forward.

But far beyond winning and losing, tradition, at long last, returned to Boston last season. Tradition? During the golden years, the Celtics knew they were in a big game, because Russell always threw up before the warmups. Then the sixth man, Frank Ramsey, would toss in three quick baskets at the conclusion of the warmups.

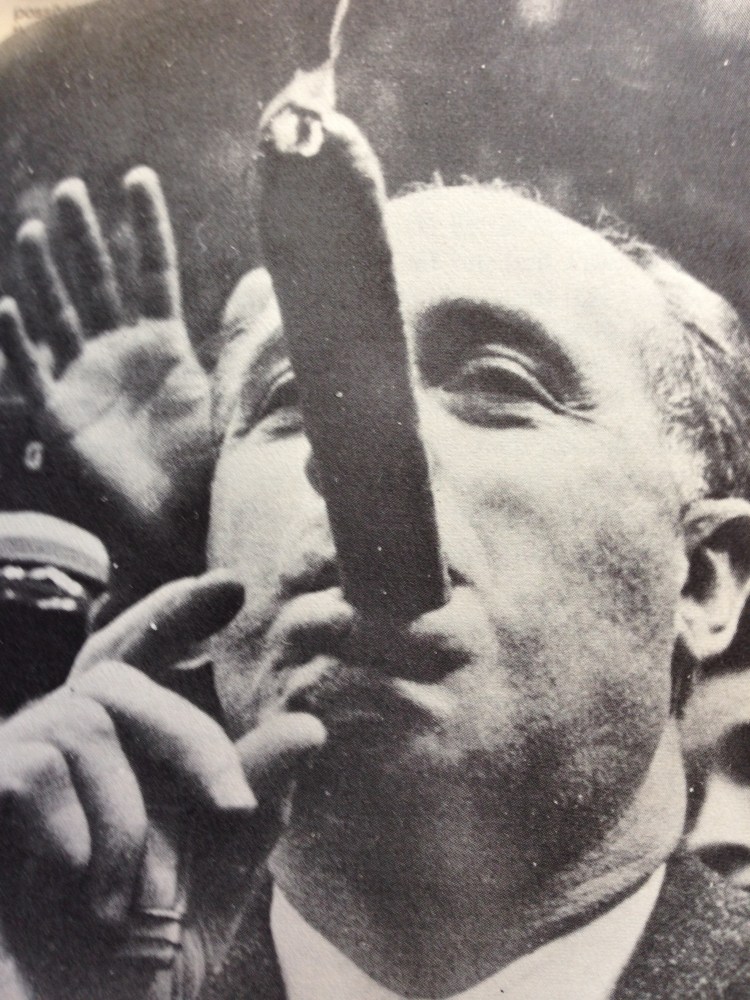

It was not much different last season. Cedric (Cornbread) Maxwell replaced Russell’s ritual with a post introduction, pregame dash to the men’s room. Cowens assumed the chore of tossing in the final three baskets after the Celtic warmup. In the stands, Auerbach had a few cigars waiting in the breast pocket to light up in victory. The Celtics were again a family.