[In the late-1990s, the Knicks and Heat went to war in the NBA playoffs. The series was brutal, low-scoring, grind-it-out halfcourt basketball. I remember reading Phoenix’s Jerry Colangelo, by this time an NBA lifer dating back to the 1960s, grumbling afterwards something to the effect: Who wants to watch grown men beat on each other for 48 minutes? There’s nothing entertaining in it, and the NBA is in the entertainment business.

His response to the brutality, along with the concurrence of others in NBA executive suites, led to rule changes that opened up the floor and hastened the NBA’s evolution into today’s best-of-times, worst-of-times style of play. The ball movement and shooting can be spectacular on some nights for a few quarters. But too many games turn into long-range shootouts that miss the mark over and over and over again. Throw in the trend toward “ole” interior defense, and the NBA has a few problems to fix. And yet, there’s no denying it. The NBA’s current constellation of stars, from the ageless LeBron to young Wemby, has never shone brighter.

What follows is a really good article that takes a look at the presumed viability of the Colangelo Committee’s rule changes in a halfcourt, defense-oriented league. Back then, the Sacramento Kings were Kings of wide-open NBA play, and we should never forget the likes of the late Pete Carril, Geoff Petrie, and Rick Adelman for building a team that was the flashpoint for the great things to come in San Antonio and Golden State.

The article, which appeared in the December 1999 issue of Hoop Magazine, was written by USA Today reporter Greg Boeck. His sourcing is excellent, and so is his writing. Definitely worth the read.]

****

Pete Babcock’s routine was the same after every Atlanta Hawks home game last season. “I’d get home,” said the Hawks’ general manager, “and the first thing I’d do is turn on NBA League Pass DirecTV and look for a Sacramento game. They were the most fun team to watch last year.

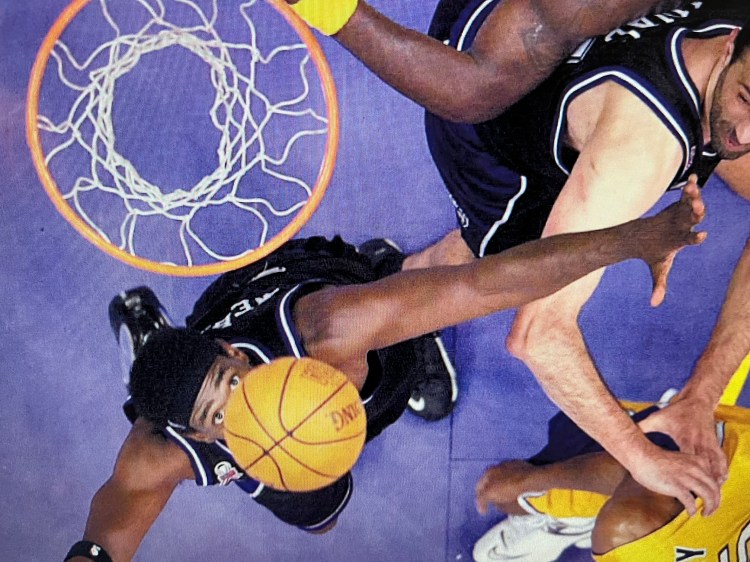

Talk about King-sized entertainment. The Sacramento Kings made channel surfing for Jason Williams’ latest behind-the-back pass and Chris Webber’s next break-ending jam a league-wide phenomenon. Transition game? Trash the 1990s-speak. The Kings flat-out fast-broke their way into nightly highlight films, the playoffs, and the hearts of everyone who loves baseline-to-baseline basketball mayhem.

“Loosey-goosey basketball,” New Jersey Nets coach Don Casey called it.

Their high-octane offense played at Concorde-like speed with laser-precision passing, conjured memories of 1980s hoops. It was Showtime on the West Coast all over again. Run. Pass. Shoot. At 78 rmps, it was, well, Magical.

But this was more than a trip down memory lane, when the Magic Johnson-directed Los Angeles Lakers and Larry Bird-orchestrated Boston Celtics stockpiled titles with breakneck basketball. While the Kings are a nostalgic flashback to an era of 120-110 free-for-alls, they were also a flashpoint to the future, at the cutting edge of the rebirth of the running game and, perhaps, the return of scores that routinely smash the century mark.

Make no mistake. Halfcourt basketball is still the rule rather than the exception in the slowed-down, defensive-minded NBA. “I still don’t see teams running fastbreaks in terms of two wings and a trailer,” said former Detroit Pistons star Isiah Thomas. “There is really no early offense. Everything is really out of sets now.”

Starting with the defensive-oriented Pistons of Detroit in 1989, teams with defensive mindsets and finely tuned, half-court offensive schemes have ruled the league. The Chicago Bulls packaged the triangle offense featuring Michael Jordan and in-your-Nikes defense into six rings. The Houston Rockets won two championships with an unstoppable inside-outside game anchored around 7-footer Hakeem Olajuwon and three-point bombardiers.

And the freshly minted new champions, the San Antonio Spurs, blitzed through the 1999 NBA playoffs with a twin-towered, in-the-paint duo of David Robinson and Tim Duncan who wreaked havoc at both ends of the floor. They capped their crowning climb in the NBA Finals with a five-game slam dunk of the New York Knicks, whose Patrick Ewing-less, makeshift, run-gun, guard-oriented offense triggered by Latrell Sprewell and Alan Houston wasn’t quite ready for prime time yet, but did manage to steal a game in the Finals.

But thanks to the Knicks’ unexpected postseason success, Sacramento’s contagious open-court play, and new rule changes and interpretations designed to reward quickness and finesse instead of brute power, there is a budding movement afoot back to the full-throttle running game.

“I think there is a tremendous emphasis around the league to go in that direction,” said Babcock. “We, for one, feel we have a great need to play up-tempo to be competitive.”

The Hawks learned the hard way. In the second round of the playoffs, their stand-around, half- court offense was no match for the Knicks. “Their speed and quickness ran us in the ground,” said Babcock, “and I see it league-wide.”

So, the Hawks reconfigured in the offseason, trading for two finesse guards—Isaiah Rider and Jimmy Jackson in a deal with the Portland Trail Blazers. “We have to play that type of game,” said Babcock, “and I see it league-wide.”

Even Houston is making the transition. Although aging Hall of Famers-to-be Olajuwon and Charles Barkley remain the Rockets’ bread-and-butter in their post-up offense, they are younger and more athletic this season with the acquisitions of swingman Shandon Anderson and rookie guard Steve Francis, two slashing, run-the-floor types.

“With the new rules with less contact, the league is trying to promote a more attacking type of game, slashing, driving to the basket,” said Rockets coach Rudy Tomjanovich. “I think Shandon is one of the most tenacious drivers in the league, and we’re going to try to present some situations where we exploit that strength.”

Scottie Pippen left Houston, but his trade to Portland only made the Trail Blazers doubly dangerous to play. Now they can either pound you in the halfcourt with a front line of Arvydas Sabonis, Rasheed Wallace, and Brian Grant, or run-you-to-death with a small-ball lineup featuring Pippen, Steve Smith, Damon Stoudamire, Wallace, and Grant.

That’s exactly how the Utah Jazz made back-to-back Finals appearances in 1997 and 1998. They are widely hailed for their half-court, fundamentally rooted, pick-and-roll game. Less celebrated but no less devastating is Utah’s fill-the-lanes running game, often started with a Karl Malone rebound and climaxed with a John Stockton-to-Malone layup at the other end.

If Malone is the prototypical power forward who can run the floor, Kevin Garnett in Minnesota is the small-forward-of-the-future—big enough at 6-feet-11 to guard power forwards and quick enough to fly past smaller small forwards. He’s the reason the Timberwolves are looking to run into the next millennium.

“I don’t like 74-72 games,” said Timberwolves Vice President of Operations Kevin McHale, a product of up-tempo basketball with the Celtics in the 1980s. “I think there is a conservatism that has crept into the league. For some reason, it’s nobler to lose 79–75 than it is to lose 115–107 and, realistically, you have a lot more chances to win that 115–107 game, because there are more runs and more possessions.

“I hope more teens start to run. Coaches may say people don’t appreciate good defense, but you know what? Good offense beats good defense all the time. If I have the ball in my hands and I’m at the top of my game, I don’t care who’s guarding me. He’s not going to stop me, because I know where I’m going—and I have the ball. By nature, basketball is an offensive game. Sometimes, we get confused between good defense and bad offense.”

The teams most inclined to rebound-and-run are those with lightning-quick guards around whom they can build their offenses. Philadelphia with Allen Iverson, Eric Snow, and Larry Hughes in the backcourt, New Jersey with Stephon Marbury and greyhound-like Kerry Kittles, and Phoenix with Jason Kidd and Penny Hardaway fit into this new mold.

You can’t stop what you can’t touch, and the new rules—specifically, the prohibition of forearm checking above the free-throw line—are designed to encourage green-light hoops. “Of the 29 teams, 25 of the offenses are basically the same,” said Rod Thorn, NBA Vice President of Operations. “And I dare say that the majority of teams don’t have a secondary fastbreak in their playbook anymore. We’re hoping this will get offenses to do some different things. We want to see some different looks and attacks.”

Phil Jackson, for one, doesn’t see a wholesale change in offensive mentality, however. He’s the new coach of the Lakers who brought an old look, the Bulls’ triangle offense, west.

“I don’t see the running game coming back,” he said, “because there are too many stops in the game, a zillion of them. You just can’t get any momentum in basketball. Then you throw in the commercials for national TV, and there are something like 17 to 20 more stops. So, you have a game that is herky-jerky, maybe at the most three to four minutes of uninterrupted play. And you can’t play basketball unless you get a running, flowing type of game.”

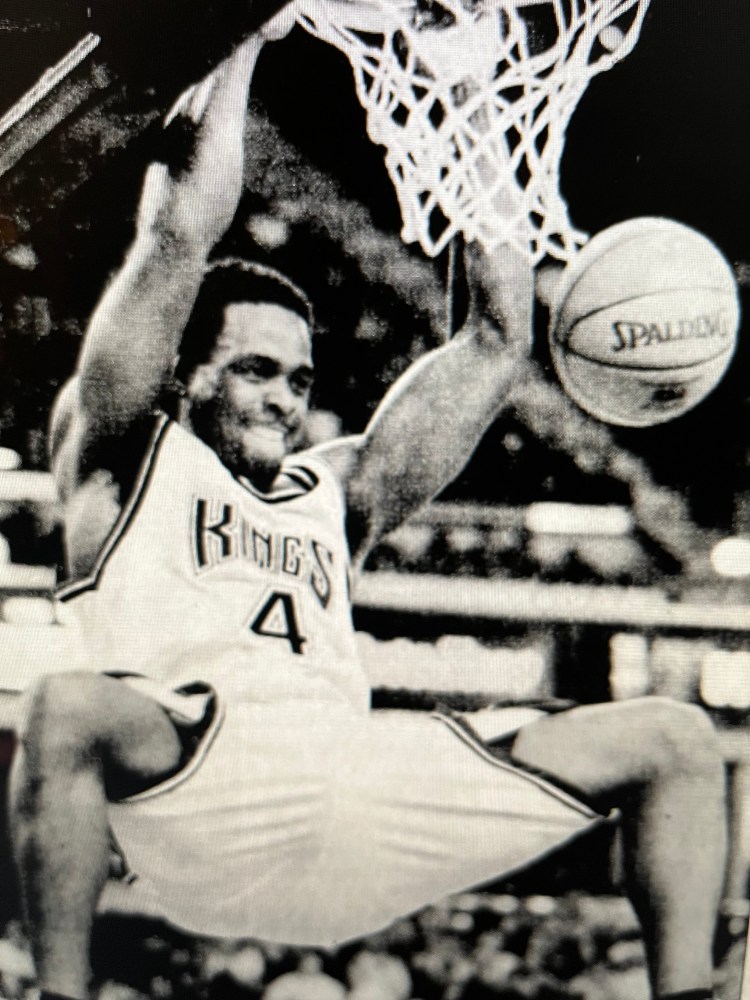

That’s Kings basketball, a style embraced by fans, TV, and the league, if not by job-wary coaches who want to control the game with halfcourt sets. One of Sacramento’s biggest fans: NBA Commissioner David Stern. “They demonstrated they’re an exciting team,” said Stern. “Their style of play is upbeat. They are clearly the prototype of the team of the millennium.”

Not surprisingly, they are the new darlings of the NBA. Once TV outcasts, they will appear on TNT or NBC 20 times this season. They even showed off their wares in Japan in two regular-season games against Minnesota in November.

“For the running game to flourish, coaches and fans will have to accept that on some nights their team will lose by 15 or 20 points,” said Thomas. “And I don’t know if coaches are willing to accept that. That’s what sets the Kings apart. Some nights, they’ll win by 10; some nights, they’ll lose by 10. But Geoff Petrie [Kings’ Vice President of Basketball Operations] believes in that type of basketball and understands there are going to be scoring swings, and he’s comfortable with his coach playing that way. So, he doesn’t panic when they lose by 12.”

Said Petrie: “What people saw was a different kind of game. They saw a more wide-open game, a team that passed the ball and enjoyed playing with each other. And they really looked like they were having fun.”

They did, emerging from the 1998-99 season as the only team to average 100 points and nearly upsetting the Jazz in a scintillating, five-game playoff series. “We have a lot of players who are very skilled,” said Petrie. “A lot of people who are attracted to that. To me, pure, physical strength is not a basketball skill. What we’ve done to go forward is to put a higher emphasis on the actual skills of the game.”

More and more teams are following their lead.

“People should get excited about a team like Sacramento,” said Hawks coach Lenny Wilkens. “That’s the fun part of the game, to get out there, create, penetrate, dish, see the spectacular play. People like that. I think every team wants to run and get out and push the ball. As coaches, all of us have to buy into that, because it’s going to make the game better, and the game has to be bigger than your team.”

Great story. I consume a lot of NBA content, but this blog is the only source that makes me stop everything I’m doing to read whenever a new post pops by my email. Great work!

LikeLike