[Bill Russell retired at the end of the 1968-69 season, leaving Bostonians to wonder who would dare to fill the giant sneakers of the then-arguably greatest player of them all. On August 22, 1969, Boston got its answer. Celtics GM Red Auerbach stepped to the podium and announced that the team had purchased from San Diego the contract of rising third-year veteran Henry Finkel. Around the city, the announcement elicited a collective: Who the hell is Henry Finkel?

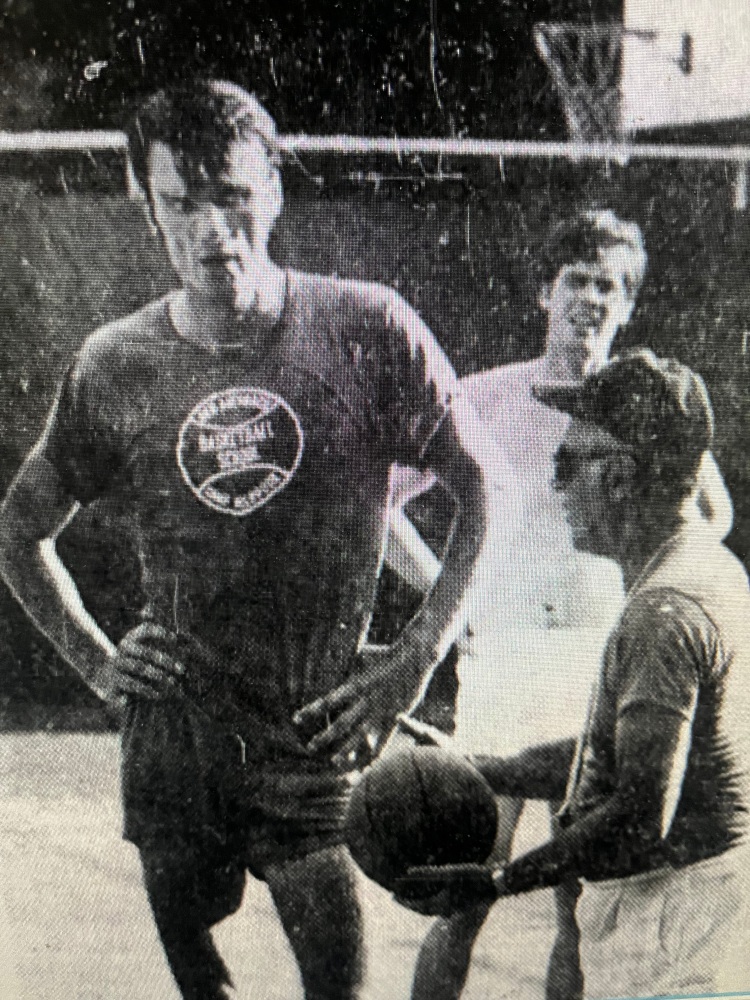

Finkel, looking like a villain from a James Bond movie, arrived in Boston a few days later to work out with his new team. He wore a green T shirt (photo below) bearing the words “Red Auerbach Basketball School—Camp Milbrook.” “He didn’t look bad,” Auerbach said afterwards of Russell’s seven-foot, 240-pound replacement.

By October, with the 1969-70 season prepared for tip-off, the Celtic Dynasty had one last dying hope: Finkel. “Look,” said Celtic veteran Larry Siegfried, “it all depends upon what Hank does. If we can get the ball and get the shots, we’ll be all right. If we can’t get the ball and get the shots, we aren’t going nowhere.”

And so, all eyes locked on the new guy “with the name of a next-door neighbor in a television comedy.” Finkel played hard, but his lumbering limitations inside the paint soon became obvious. He couldn’t jump, couldn’t rebound, and, sacré bleu for anyone replacing Russell, couldn’t block shots or dominate defensively. The leather lungs in Boston Garden mocked him mercilessly. Bob Ryan picks up the narrative in his 1975 book Celtics Pride:

The big man had everything going against him. Succeeding the greatest player of all time was bad enough. But having a humorous name, a large head (he was no threat to the male models of America), and awkward movements, compounded the problem. His teammates weren’t always helpful either. Havlicek, who had yet to develop his skills fully as a passer (he would by the end of the season), continually fed Finkel bullet passes on the pick-and-roll that would have tested the ability of a [NFL receiver] Lance Alworth. John threw his passes far too hard, but when they bounced off Finkel’s fingers, it was the poor center, who got the boos and suffered the insults, and not the superstar.

[Boston coach Tommy] Heinsohn knew that Finkel just wasn’t going to be the answer. It wasn’t going to be a matter of playing Henry for 40 minutes and giving him a little breather with [backup “Bad News”] Barnes. If the Celtics were to have any chance of beating certain teams, they would have to do it with a relay system. Hence, Bad News Finkel Barnes, Boston’s two-headed center, was born.

Bad News Finkel Barnes soon gave way to the rookie revelation named Dave Cowens. Finkel, the guy “with the name of a next-door neighbor in a television comedy,” then became a seven-foot tool in Heinsohn’s toolbox. He got spot minutes when his size, soft jump shot, and six fouls were needed. He also became a mostly beloved crowd favorite in Boston for six seasons (1969-1975).

But before Bostonians turned warm and fuzzy about Finkel, long-time NBA scribe Milton Gross wrote the following article about Bill Russell’s unfortunate replacement and wrath that awaited him. The article ran in the April 1971 issue of the magazine Sports Today under the headline: “7 Feet of Frustration.”]

****

The Metropolitan Basketball Writers Association of New York was staging its annual frolic and, as usual, the feature was not the food, but the fun—at somebody else’s expense. The target for the night was Henry Finkel, a seven-footer who had mysteriously disappeared from the campus of St. Peter’s of New Jersey and reappeared as the center of the basketball team at the University of Dayton.

The scribes could not let such an incident go, unnoticed, or unsung. They put it to verse, if not worse, and borrowing from Lerner and Lowe’s “Mimi,” they warbled:

Finkel—you’ve got me mad and grieving

Please don’t be leaving, you’re deceiving.

Finkel—I know you’ll be an All-American;

Finkel, you’re the blinkel of mine eye.

The reprise is still being sung, and it’s still a lampoon. Henry Finkel is a 28-year-old who can fairly be described as seven feet of frustration, of sensitivity, or despair turned into resignation, of anger converted into acceptance.

Henry Finkel knows what he is. He knows what he can do. He knows how people are going to look at him from the stands, and what they’re going to shout. He wears the uniform of the Boston Celtics, and he likes that. But he doesn’t like the epithets and snide characterizations that are spewed at him. He is damned if he does, damned if he doesn’t, and damned if he knows what to do about it within the limits of his talent and the temper of our times.

“Tall guys get abuse anyway,” says Finkel. “They get more than shorter guys, and if [the fans] don’t know by this time that I’m no Bill Russell, they’ll never know it.”

Who is? But Henry was in the unfortunate position of being the seven-footer the Celtics got when the 6-feet-10 Russell retired as incomparable center and then player-coach after leading the Celtics to their unprecedented string of National Basketball Association championships. In the best of circumstances, he would be by comparison the object of ridicule. But he was thrust into the worst of circumstances. The Celtics were going from champions to also-rans, and in such a situation, the fans look for a scapegoat. The seven-foot Finkel was easy to see.

A season and a piece have passed since Finkel was pushed into the situation. He did not seek it, still does not like it, and would disown it if he could. Yet still, such things as this happen to him:

The Celtics were playing the world-champion Knicks at Madison Square Garden earlier this season. Toward the end of the first quarter, coach Tommy Heinsohn’s young rebuilding team held a tenuous 22-20 lead. Finkel was sent into the game to replace Garfield Smith, a 6-feet-9 rookie, with 3:22 left in the period. A pass was thrown to Finkel. He fumbled for it, and it went through his hands. The Knicks recovered, and Walt Frazier, their ubiquitous guard, quickly made a basket. Dave DeBusschere was fouled and converted. Bill Bradley followed with another basket. Before you could sing “Finkel, you’re a blinkel of mine eye,” the Knicks took a 29-27 lead at the quarter and went on to win, 114-107.

“Hey, Heinsohn,” a foghorn voice exploded from the stands, “how long you going to stay with that spastic?”

“The fans pay their way into the arena,” says Kathy Finkel, Henry’s 5-feet-8 wife, mother of his 3½-year-old son, Denny, and pregnant with their second child. “But paying their dollars doesn’t give them the right to be so rude and unfeeling. They have the right to criticize, but you can take so much.”

In this case, the female of the species certainly is the more deadly. Finkel says he hears some of the comments, they bother him, but he is able to walk away and forget them. Of course, he may be deluding himself as a defense mechanism against the abuse.

Kathy, who calls herself “Garrulous Gertie,” doesn’t walk away. She steams. “I don’t break into tears. That’s not my style. I get hot, red hot,” she says. “We have the big image—Hank replacing Russell—and there was no way it was humanly possible. People should have realized it when the Celtics got Hank from San Diego, but people are cruel. Maybe somebody else would burst into tears, but not me. I bellyache all the way. Hank doesn’t complain. He keeps it inside. I am the complainer. I let it out.”

All the way for Kathy goes back to Dayton when she and Finkel were courting. Kathy would sit in the stands and listen to some of the comments and explode. “We were playing at Loyola of Chicago,” recalls Finkel, “when somebody said something derogatory about me, and Kathy just turned around and hit him with her pocketbook.”

“Oh,” replies Kathy, “you know about that one. Well, that only happened once, but I was so angry. I just couldn’t sit there and listen without reacting. I slugged him. I should have kept my purse to myself, because after I hit him, I was so frightened. I thought he would take me to court or something.”

“Kathy was so embarrassed by the incident that she got up and ran away,” Hank remembers. “She realizes now that comments are a dime a dozen, but she still has to say something in defense.”

She may realize it, but that doesn’t make it easier for Finkel’s wife. She cannot sit quietly by as the game goes on. People get to know her, and so they bait her, just as they blaspheme her husband.

“Men blow smoke in my face once they realize I’m Mrs. Finkel,” she says, “although this season it is certainly better than it was last year. The team’s been better. Hank’s been better, and the ghost of Russell’s no longer behind Hank.”

But it isn’t only Russell’s ghost. The problem is really Finkel himself. He is a quiet, gentle man, who never could hide in a crowd, not even when he was a youngster back in Union City, NJ. He discloses that he’s always had a complex about his height. As a grown man, he can now take such a ridiculous comments as, “How’s the weather up there?” But as a child who stood 6-feet-10 and was extremely thin when he entered Holy Family High School, being different was almost more than he could bear.

“It wasn’t just being so tall,” says Finkel, “it was being so skinny. I was a good shooter in high school, but never a good rebounder, and it made me miserable. Even now, when a big man performs poorly, he experiences a sense of frustration. It’s like the people getting on Wilt (Chamberlain) for missing free throws. A guard does something wrong, and it is hardly noticed. A man of my size performs inadequately, and he cannot miss being noticed.”

Certainly, there is no place to hide, and Finkel would not want to. “I realize I’m in the NBA only because of my height,” he says. “I also realize my shortcomings, but I’ve got to make the best of what I’ve got.”

The trouble, of course, is that basketball fans, especially those who have become accustomed to the grace of the breed of agile giants who perform in the NBA, somehow seem compelled to make fun of the homely, awkward-looking Finkel. A man who is 5-feet-7 or 5-feet-8 and stands eyeball to belly button with somebody Henry’s size feels an almost irresistible urge to put him down. In Atlanta recently, Finkel went up for a loose ball. He came down with it, but he came down hobbling. A fan behind the press box laughed aloud. “Now, there’s a real klutz,” he shouted. “That’s a glandular case if I ever saw one. Put him in sneakers, and that’s supposed to make him a basketball player. Phew!”

Finkel sat on the bench the remainder of the game. His leg was heavily wrapped in a pressure bandage under which squat, short Celtics’ trainer Joe DeLauri had applied an icebag. The Celtics beat the Hawks without Finkel, but for the next few days, Henry could barely walk. Nevertheless, the callous fan’s parting remark was, “Finkel, you stink, even with the ice.”

Now that’s unnecessary and completely unfair. Finkel is not Russell. Nor is he Chamberlain or Reed or Thurmond or Alcindor, all of whom are extremely more agile, adapt, and natural. Henry’s agility is not great. He does things almost mechanically, but as Johnny Most, who broadcasts the Celtics games, says, “If Henry makes a mistake, he gets the dirtiest end of the stick all the time. If he misses on a play, he’s disjointed. If somebody else misses, they’re nervous.” Most knows. His wife and Finkel’s wife are close friends.

Most should know a good deal about what goes on inside this big guy. When Finkel came to the Celtics, after being with Los Angeles and San Diego, the broadcaster began to refer to him as, “High Henry.” It is characteristic of Finkel that he came to Most and asked that he be called by another nickname.

“Sure,” said Most, immediately beginning to see the promotional potentialities of a contest to give Henry a nickname in the request. He anticipated having a poll conducted of his listeners, with the contest winner getting some sort of a reward for coming up with some highly descriptive nickname that would make the fans forget the disparaging ones. How about Foothills Finkel or Himalaya Henry? But Finkel didn’t shine to the idea of having a contest at all. Nothing that would focus attention on him.

“What would you like to be called?” Most asked.

“Hank,” said Finkel. “That’s what I was called in high school and college and what my wife calls me.”

Again, we have a significant insight into the Finkel psyche. Wilt Chamberlain has “Dipper” monogrammed on his shirt cuffs and painted on the side of this luxurious Bentley and Maserati. Lew Alcindor is Mount Alcindor and was LewCLA in college. Russell drove a Lamborghini, wore a cape, and was the first to grow a beard. Finkel, 10 years later, would prefer to have an interviewer forget that he jumped from St. Peter’s to Dayton and why. He also deftly steers the conversation elsewhere when another incident is mentioned in which he was the center of attraction for the Celtics.

The Celtics made a presentation to Henry in a mock ceremony that is part of the camaraderie of a team. They were on a plane taking off for a roadtrip when captain John Havlicek summoned all the players to the lounge of the first-class section. With all the pomp and circumstance that should be invested in a knighting, Havlicek presented Finkel with a two-foot-long comb. Finkel must have assumed somebody was trying to tell him something. Immediately afterward, he changed his hair style.

“At the time,” says Henry, “I was growing my hair longer and had it all pushed back. They were calling me all kinds of names like ‘Flip Wing,’ so I decided to change the styling.”

Now Finkel wears his hair parted and has grown a mustache again. But if there is anything to be deduced from the comb ceremony, it is that the players decided that Henry should not consider himself different but part of the team. Basically, Finkel is a quiet person, the kind who finishes a game and then goes home. He’s not particularly gregarious, but he is well-liked by his teammates, and the ceremony was meant to make him understand that.

None of the Celtics pretend that Finkel is anything but what he is. He is not quick, but he is able. He does not stand out in any particular area of the game, but he fits into the scheme of things better than he did last season, and there are moments when his particular ability—a fine shooting touch for a big man—is just what the situation demands. It’s taken him a full season to believe that he belongs and rid himself of both the doubts which assailed him and the speculation, that with Russell gone, management acquired him only because it had to acquire somebody, a big body, to try to fill a role nobody could fill.

Why he should feel that way is understandable. Finkel came into the league with the Lakers for the 1966-67 season, went in the expansion draft to San Diego on May 1, 1967, and was sold to Boston for cash and a draft choice on August 22, 1969, With Los Angeles and San Diego, he played a total of 1,589 minutes in three seasons. With the Celtics last season, he played a total of 1,866 minutes. He was able to contribute, although Kathy still sat through a lot of the games with her head bowed because she didn’t want to hear the crowd. “The things they shout about Hank,” she told Mrs. Most once, “and it upsets me.”

“What it was really,” says Finkel, “is that Kathy felt that the home crowd shouldn’t have acted that way. This year, it’s been so much better. Last year, the fans were disenchanted, and I was the one they took it out on. I was the guy to take Russell’s place.”

“People just expected too much of Hank,” says Kathy. “He’s not Chamberlain or Havlicek, either. It bothers me when people expect him to play like them. I know Hank doesn’t like my reactions. But it’s not so bad this year. Things are better, and his attitude is so much better. Last year, he was so nervous and so much of it was so unfair.”

“What was in my mind so much of the time.” says Hank, “was that I had to be good enough to help get the team into the playoffs. I was trying to do better, so I pushed myself. I should have played my normal game, but the extra pressure put my whole game out of whack.”

What is normalcy for an awkward seven-footer who frankly is simply not a natural athlete? What is normal for one man is not for another. Criticize Alcindor or Chamberlain or Russell, and they become angry and try to tear you apart. Finkel hears himself called a freak or a goon or a spastic, and it distresses him. “You don’t have to be special,” he says. “Everyone is sensitive to criticism.”

Maybe Finkel has rabbit ears. Maybe he has a right to have them. Give him a spot on the left side of the key, and he may not be able to shoot the eyes out of the basket, but he’s gotten to the stage where he’ll make his share. If the defense comes out on him now, he’s learned to step aside and go for the hoop. He doesn’t do it gracefully. He never will. Grace is not his bag.

But it is even more graceless for a fan to sit in the stands and shout insulting remarks at the man just because he happens to be seven feet tall and wears a professional basketball uniform. Not all good things come in little packages, and maybe some of those little people who degrade this soft-spoken giant are experiencing more frustration than even Henry Finkel.

It’s something Kathy thinks about. She’ll never forget, the cruelty that spurred her to hit the man with her purse. “Hank was hurt, and yet he tried to play,” she remembers, “but finally it became too much. He had to sit down. A man sitting next to me said, ‘That kid deserves an Oscar for the act he’s putting on.’ So, I let him have it.”

Finkel will never get an Oscar. It’s unlikely he’ll ever make an all-star team. But one thing is certain. He tries. Oh, how he tries, despite the abuse that are like darts tossed at him. Some men just are spear carriers. When the spear carrier’s seven-feet tall, awkward, and homely, he looks funny. But inside, he’s not laughing.

Imagine if Caitlin Clark did that her centers like Havlicek did. Credo to Kathy Finkel for standing up to her man.

LikeLike