[No need for an introduction here, the headline and opening paragraphs below tell the whole story. But I will add that the byline belongs to Don Brown, a name way too generic to pin down over a half century later, and his article appeared in the magazine Pro Basketball Almanac, 1968. Enjoy!]

****

He’s a veteran ballplayer who didn’t quite live up to his college All-America promise his first couple of years as a pro. But he’s learned his trade gradually—and well—and now he is indispensable to his ballclub. He is not usually the high-scorer, and even if he leads his club in rebounds or assists, he’s usually no more than fourth or fifth in the league’s overall individual figures—behind the superstars.

In addition, he performs in a publicity vacuum. The fans don’t respond to him, and the newspaper headlines go to his rivals and teammates. But both rivals and teammates know how much he means to his ballclub. They understand, and the coaches understand and pay him his due.

He is the underrated player. Every team has one, and each is the lifeblood of his team. But in the NBA, some underrated players are better than others—and some are more neglected than others. To learn just who the best—and most—underrated players are, PRO BASKETBALL ALMANAC surveyed coaches, scouts, general managers, and players from every NBA city and came up with five names: Adrian Smith, Cincinnati Royals; Bill Bridges, St. Louis Hawks; Lucious Jackson, Philadelphia 76ers; Dick Van Arsdale, New York Knickerbockers; and Jerry Sloan, Chicago Bulls.

Here is why they rate so high.

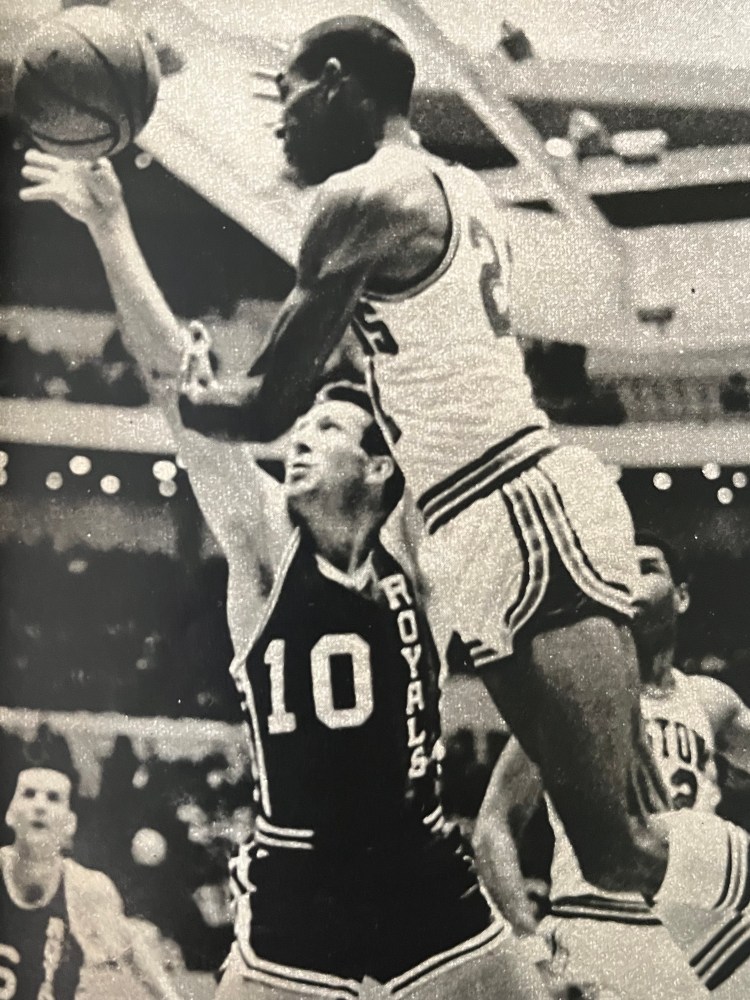

Almost all of the basketball people questioned put Adrian Smith near the top of the underrated list. The 6-feet-1 backcourter fits in two ways. First, anyone who plays guard alongside Oscar Robertson is bound to be underrated and almost unnoticed. Second, the former Kentucky All-America came into the NBA six years ago and averaged just 7.2 points per game as a rookie. Though he steadily raised his average two or three points per year to a high of 18.4 in 1965-66, he’ll probably never be able to change the image formed by his modest beginnings.

For an appraisal of Adrian Smith’s qualities, we talked to Jack McMahon, coach of the NBA’s San Diego Rockets. He coached Smith for four years at Cincinnati. “Although Odie is a fine ballhandler,” said McMahon, “Oscar handles the ball about 80 percent of the time, as he should, and you never get the chance to see what Odie can do with it. But that doesn’t matter because offensively Odie’s job is to shoot, and he’ll shoot your eyes out if you let him. He can get off a good shot faster than anyone in the league.

“He’s also the best foul-shooter in the NBA (Smith had a league-leading .903 percentage in 1966-67), and I’ll bet that he took 50 or 60 technical fouls for us last year, many of ‘em crucial, and never missed one.

“But the big job that he really does for Cincy is defensively. Though he’s only 6-feet-1, he goes 110 percent on defense all night, dogging the Greers, the Sam Joneses, the Wests, giving away a lot of height, but making those guys really work and press for their points. This gives Oscar a slight breather defensively and keeps him from getting into foul trouble. That’s something the fans never think about.

“Another facet of Odie’s game,” said McMahon, “is how he helps the overall defense. When the opposition gets its fastbreak going, who’s always back there to break it up but Smitty? I’d say maybe 150 times a year Odie’s back there by himself facing the fastbreak, and he puts himself in the way of some thundering elephant and draws the offensive foul, breaking up the play. That destroys the other team’s momentum and can really turn the game around.

“I remember once last year, we were playing the Celts, and Odie, as usual, got back on the break, just in time to be run down and over by Tom Sanders (6-feet-6, 210). He hit the floor hard and lay their motionless for a moment. Finally, after what seemed like an eternity, Odie struggled to his feet and limped back toward the action. ‘Odie, are you all right?’ I yelled. ‘Don’t worry about me, Coach,’ he mumbled back through split and puffed lips. ‘The bigger they are, the harder I fall.’”

Adrian Smith did have one brief, shining moment in the spotlight. In the 1965-66 All-Star Game, as befits an underrated player, Adrian made the last spot on the East squad by a wafer-thin margin over Dick Barnett of the New York Knickerbockers, who seemed to have the edge over Smitty in various statistical categories. A lot of people thought that Smith’s selection had more to do with the fact that the game was being played in Cincinnati than with the fact that his play had earned him the honor.

He showed ‘em. Adrian didn’t start the game, of course, but when he got in, he was hot. The smallest man on the court, the most-controversial selection, and the most lightly-regarded All-Star, Smith collected 24 points, three assists, and eight rebounds—all in just 26 minutes of play. And he received the MVP award, a new sportscar, and some long overdue recognition.

****

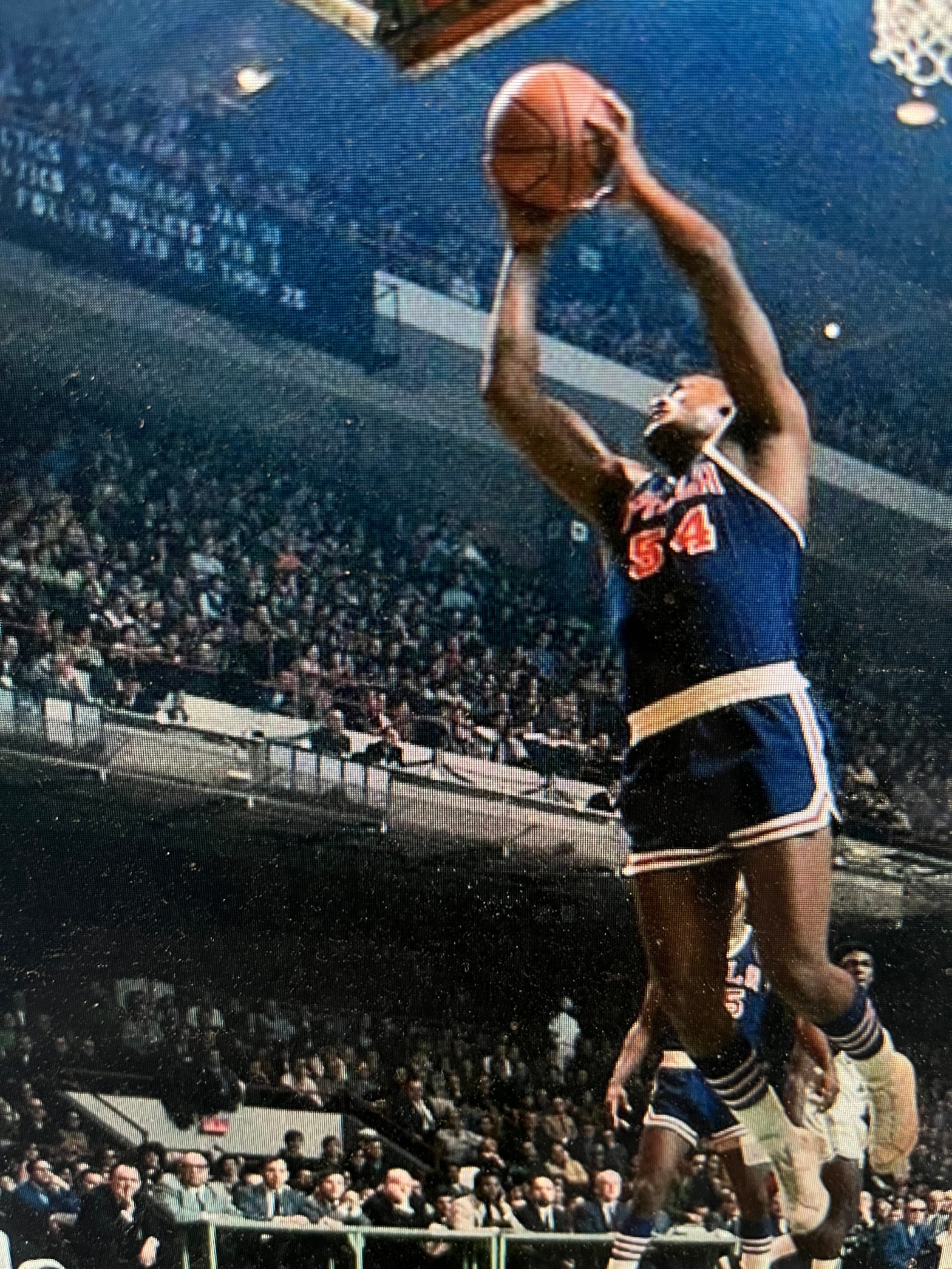

Lucious Jackson is another cup of tea. He is a hulking, muscular, 6-feet-9, 240-pound cornerman and a displaced person since Wilt Chamberlain joined the Philadelphia 76ers two-and-a-half years ago, forcing Jackson out of his natural pivot slot and into the corner. But he learned his job and was a vital force last season as the 76ers dethroned the Celtics for the first time in 10 years as Eastern Division champions. Chamberlain received most of the credit, even though it was a job he had been unable to do previously with the Warriors. He needed help, a lot of it, and most of the experts interviewed by PRO BASKETBALL ALMANAC pointed to Luke Jackson as the man who provided much of that help.

Former Celtic star K. C. Jones said of the burly frontcourter, “Luke Jackson goes up for a rebound ready to fight the world. If Chamberlain doesn’t get it first, Jackson sure will. It’s tough to beat that kind of board strength.”

Baltimore Bullet coach Gene Shue, another Jackson booster, said, “Luke’s the kind of player you need in a winning combination. He sacrifices his own figures for the good of the team. They don’t play to him, so he doesn’t score too much. He does a lot of boxing out, so Chamberlain picks up the extra rebounds. And he sets a lot of picks and blocks for his teammates’ shots, and that never shows up in the statistics. That kind of play may leave you underrated outside the league, but we know what he’s doing. That’s the price you pay to make your club a winner, but it’s worth it!”

Fred Schaus, general manager of the Los Angeles Lakers, is another Jackson fan. “Besides, what Luke does rebounding and intimidating the opposition around the basket,” Schaus said, “he helps the 76ers in another, less-obvious way. He provides center insurance against injury to Wilt, and he also provides incentive for Wilt to keep on his toes, because there is a strong back-up center who can handle his job. All these things are intangibles, which he brings to a ballclub and which may never be utilized to any great extent. But they’re there just the same, and they help.”

****

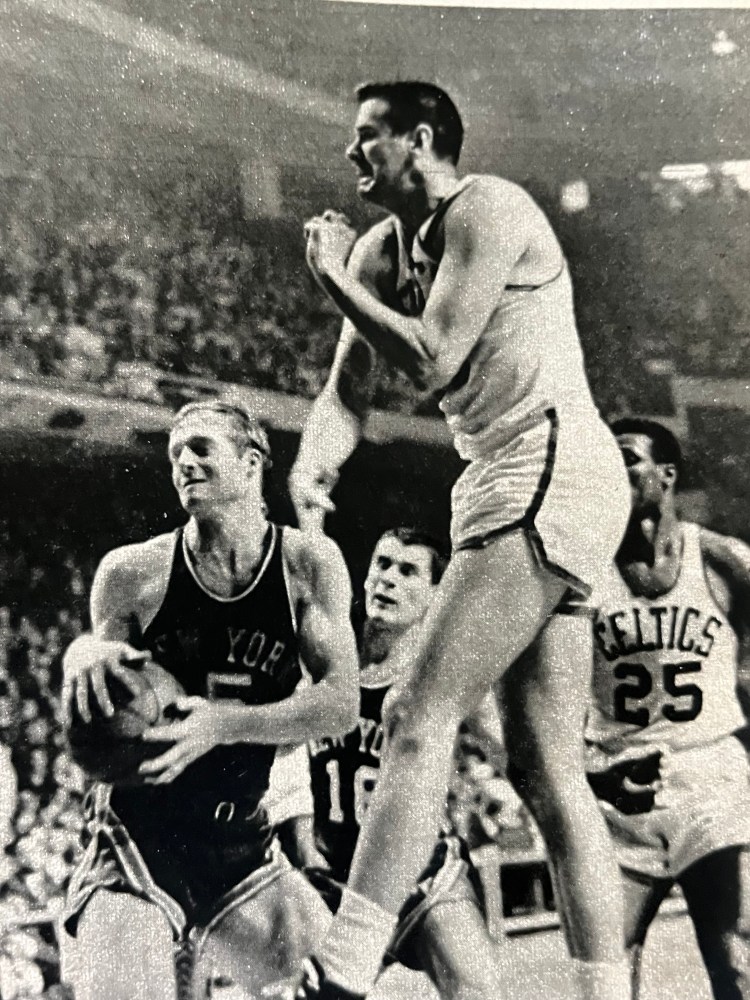

Part of Dick Van Arsdale’s problem is that he is playing with a bad ballclub. Or at least the New York Knicks have been a bad ballclub. But with potential superstar Bill Bradley signed, sealed, and set for January delivery, perhaps that will change. Dick’s other hang-up is playing on a frontline with skyscrapers Walt Bellamy (6-feet-11) and Willis Reed (6-feet-10). Though “Bells” isn’t exactly a superstar anymore, he was one when he broke into the league in 1961-62 with a 31.6 scoring average, and Reed may yet become one as he pushes his average into the 20s. Between them, Bellamy and Reed average about 40 points and 30 rebounds per game, and that doesn’t leave much for Van Arsdale up front. So, Dick does the dirty jobs. He plays the tough, agile forwards in the league, like Elgin Baylor, John Havlicek, and Rick Barry. And he doesn’t give them a moment’s peace.

“When he joined us,” said Knick general manager Eddie Donovan, “we didn’t know whether to play him up front or at guard. At 6-feet-4, he’s a little small for frontcourt, but we had a lot of guards and some room at forward. Right away, he showed us. He didn’t mind banging heads with the bigger fellows. And he showed us he could pass out more than his share of lumps, too. With big guys like Reed and Bellamy, we could afford to sacrifice height for a little more mobility from a hardnosed kid like Dick.”

And what kind of job does he do? Ask the NBA’s leading scorer last season Rick Barry. “When we played the Knicks,” Barry said, “I knew that Van Arsdale would be on my neck all night. What makes him so tough is he plays you with the ball, without the ball, and wherever you are. Sometimes it feels like he picks you up when the team bus hits the Garden before a game and doesn’t let up till you get out to Kennedy Airport.”

Red Auerbach of the Boston Celtics is another Van Arsdale man. “He’s the kind of player any coach would like to have. He hustles, plays defense, and he’s tough. And another great thing about him. They almost never play to the guy, but he gets his points. He gets about 15 a game on garbage shots. I don’t mean he can’t shoot. I mean he scores [on] follows, tip-ins, on the break—all those points when you’re not looking for him because he’s in the right place at the right time. He knows the game, and he gets the most out of this talent. Would I want him? You bet!”

****

Bill Bridges’ difficulty in getting recognition, probably stems from a slow start in the NBA at St. Louis. Part of it may be attributed to playing behind superstars Bob Pettit and Cliff Hagan, but part, too, stemmed from his being out of position at forward. Though Bill is just 6-feet-6 ½, he’s basically a pivot man with pivot shots, and he had to prove that before he could begin to play up to his potential. Seeing limited action behind Pettit and Hagan cut Bridges’ averages to 6.1, 8.5, 11.5, and 13.0 his first four years in the league. And during his third year, he recorded an awful .286 field-goal percentage.

That figure, along with his modest beginnings, is probably responsible for his relative anonymity now. That’s despite a 17.4 scoring average in 1966-67, compiled on a brilliant .458 shooting percentage, and despite the fact that he finished fifth in the league in rebounds with a fine 15.1 mark per game.

Jack McMahon was the first man to discover how to use Bridges most effectively. “I had him when I was coaching the Kansas City Steers in the old ABL a few years back,” Jack said. “I also had 6-feet-9 Gene Tormohlen, and he played pivot for me to start the season. But before we got along too far, I began to realize that Tormohlen had a great outside shot and would be better in the corner, and Bridges had the hook and little jumper that make him ideal in the pivot. I made the switch, Bridges went wild, and we romped all over the league the second half of the season. It’s a pity it took this long for Bridges to get a shot at the pivot in this league.”

That Bridges did get the chance to play the pivot and really blossom in the NBA is just another of those double-edged breaks that disables one man and makes another in sports. Hawk pivotman Zelmo Beaty, 6-feet-9, was injured early last season, and coach Richie Guerin, with no big man to replace Beaty, shoved Bridges inside in sheer desperation. And with the move, the Hawks began to win. Bridges led crippled St. Louis to a surprising second-place finish in the NBA’s Western Division, just five games back of the champion San Francisco Warriors.

One man who fully respects Bridges and his potential is his own coach, Richie Guerin. “My guy comes to play,” said Guerin, “and nothing will keep him out in some of our big games. In the playoffs, he could barely walk on a bad ankle. But we shot him full of Novacaine, and he never complained. He just went out there and played like nothing was bothering him, and he was the best we had.”

****

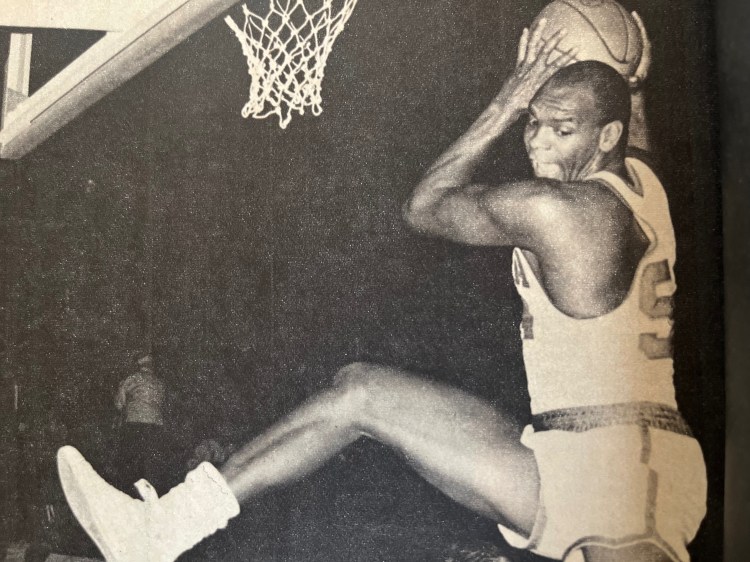

The Chicago Bulls were a bad team last year—an expansion team—but they weren’t quite as bad as everybody thought they would be. And one good reason was Jerry Sloan. It was tough to appreciate what Jerry Sloan meant to the Bulls last year, because he played guard and didn’t do the things a little man is expected to do. He scored (17.4 ppg), but he wasn’t the Bulls’ leading scorer. He passed, but Guy Rodgers rarely needed help in that department (Guy led the league with an 11.2 assist mark).

So, Sloan just helped out here and helped out there, and when they added things up at the end of the year, the “figger filberts” did a double-take. For Jerry Sloan had pulled down more rebounds than anyone else on the club—an astounding feat for a guard.

Al Bianchi, who was an assistant coach at Chicago before taking over as head coach of the NBA’s new Seattle Supersonics, says Jerry Sloan provided much of the sinew that held the Bulls together, enabling them to beat out Detroit for a playoff berth. “Jerry was all hustle,” recalled Bianchi. “He played the tough guard on defense, he got the key baskets, and he played both ends of the court. For a 6-feet-5’er, he was just amazing on the boards for us.”

****

When you come right down to the business of being underrated in basketball, the explanation is really quite simple. The name of the game is points, and a player is usually underrated because he doesn’t get a lot of points. This doesn’t mean a player can’t score. It just means that he doesn’t score because there was only one basketball, and he must do more important things with it to help his club.

A few years back, one of the most-underrated players in the NBA, workhorse Rudy LaRusso of the Los Angeles Lakers, struck a telling blow for all underrated players who don’t score because they’re too busy handling other vital jobs. Though Rudy’s game had always been to play tight defense and do the tough rebounding to free Elgin Baylor and Jerry West to do the scoring, LaRusso was suddenly called upon one night to take over the scoring load as well when Baylor and West both sat out a game with injuries.

All the Rudy did was toss in 50 points. Of course, this doesn’t mean that LaRusso can toss in 50 points on any night, but then, neither can Baylor or West. It does suggest, however, that specialists in the less-glamorous aspects of the game—like rebounding, defending, and passing—are not necessarily deficient at the headline-grabbing art of shooting. It’s just that their value lies in being able to do the dirtier jobs that some of their high-scoring teammates might not be able to do as well or as consistently.

There were other underrated players in the NBA last year, of course, and every NBA coach named two or three players on his own club. But the players we analyzed were the players whose names came up most frequently in our discussions. If we missed your favorite underrated player, we’re sorry. But it just proves that you’re right—he’s so underrated, even the experts never got to him!