[A while back, From Way Downtown ran a 1982 article chronicling the ups and downs of Billy Ray Bates, then a beloved, but enigmatic, member of the Portland Trail Blazers. Bates would self-destruct in the local spotlight shortly thereafter, blowing up his brief NBA career and sending him bouncing from continent to continent overseas. The article that follows picks up Bates’ life in 1995. He’s now in his late 30s, and the good times are all gone. All that remained are the last remnants of the dream.

This story, published in the August 1995 issue of Rip City Magazine, is a good one. You’d expect nothing less from one of the best, L. Jon Wertheimer. Today, Wertheimer’s name is linked to Sports Illustrated, where he’s done great things for nearly 30 years as a writer and editor, and as a face that pops up from time to time on 60 Minutes. But when Wertheimer wrote this piece, he was still several months shy of his Sports Illustrated gig. He’s listed as Rip City’s former assistant editor.

Bates would land on the wrong side of the law three years later and do time for robbing a New Jersey liquor store while drunk and assaulting the teenaged clerk. But before that difficult chapter in his life, here’s Billy Ray Bates in 1995.]

****

Billy Ray Bates once missed a game for the Portland Trail, Blazers because he overslept. These days, he wakes up early. Too early, to hear him tell it, “My shift starts at 7:30 a.m., so I’m up by six,” he says, laughing and shaking his head. “Can you believe that?” Bates rises at 6:00 a.m. so he can get to his $10-an-hour job at Sun Oil of Pennsylvania, where he’s “kind of like a distributor.” He’s looking to get into another line of work, but claims Sun Oil is better than his other recent occasional gigs, which have included kneading dough for a New Jersey pizzeria and stocking Coke machines. His worst job? Gluing leather onto briefcases for $7 an hour.

Bates recounts his shaky recent employment history as we drive around Sicklerville, New Jersey, a nondescript town 20 minutes outside of Philadelphia, where Bates lives in a modest apartment complex. Though he has resided in Sicklerville, on and off, for more than 10 years, Bates is having trouble finding a place where he can shoot some hoops today.

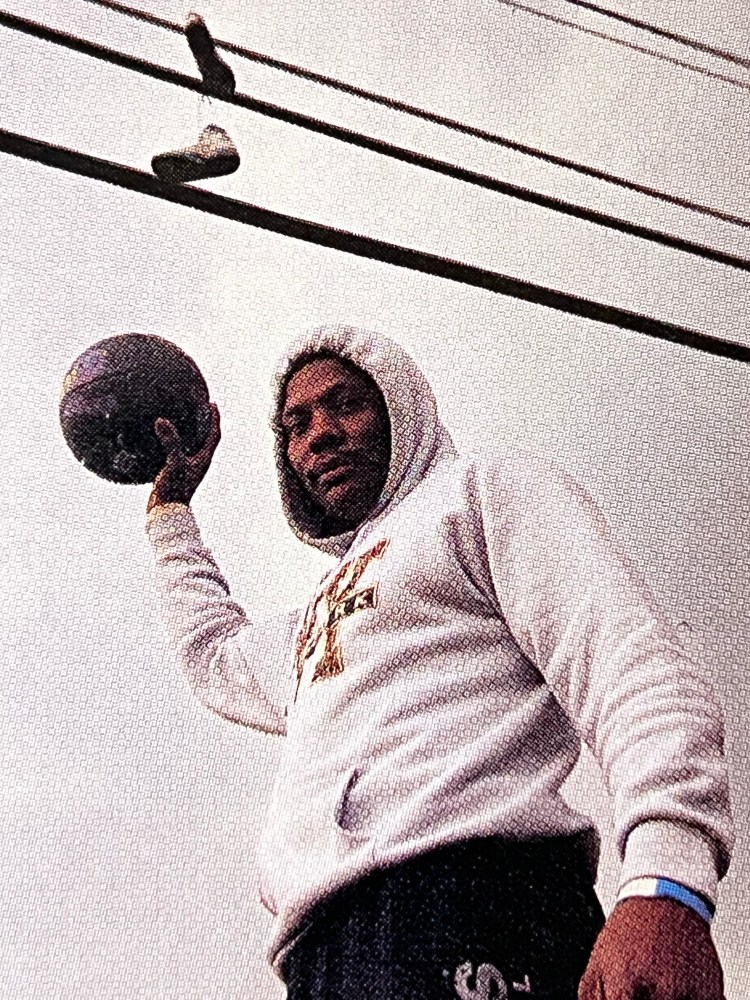

But the man with the gift of gab has no problem maintaining a hilarious-stream-of-consciousness dialogue, discussing everything from his dislike of the game of golf (“I get tired of being patient”) to his past relationships. Suddenly, he stops in mid-sentence. “See that,” he says, pointing out the window to a phone line. “A few years ago, I was so frustrated with basketball that I didn’t know what to do. So, I took my shoes and threw them up there.”

Sure enough, on closer inspection, there is a pair of size 15 Avia high-tops draped over the line. “I guess I should get them down one of these days,” he says with trademark indifference.

Now 39, the Billy Ray Bates of today is little different from the enigmatic phenom who took Portland by storm more than 15 years ago. Although he has to defend against a well- upholstered midsection, he looks extraordinarily fit. Later in the day, he shows he can still dunk and rain in three-pointers. And, most poignantly, he still has the mix of instant likability and naïve openness that made him both so popular as a player and so vulnerable as a person.

****

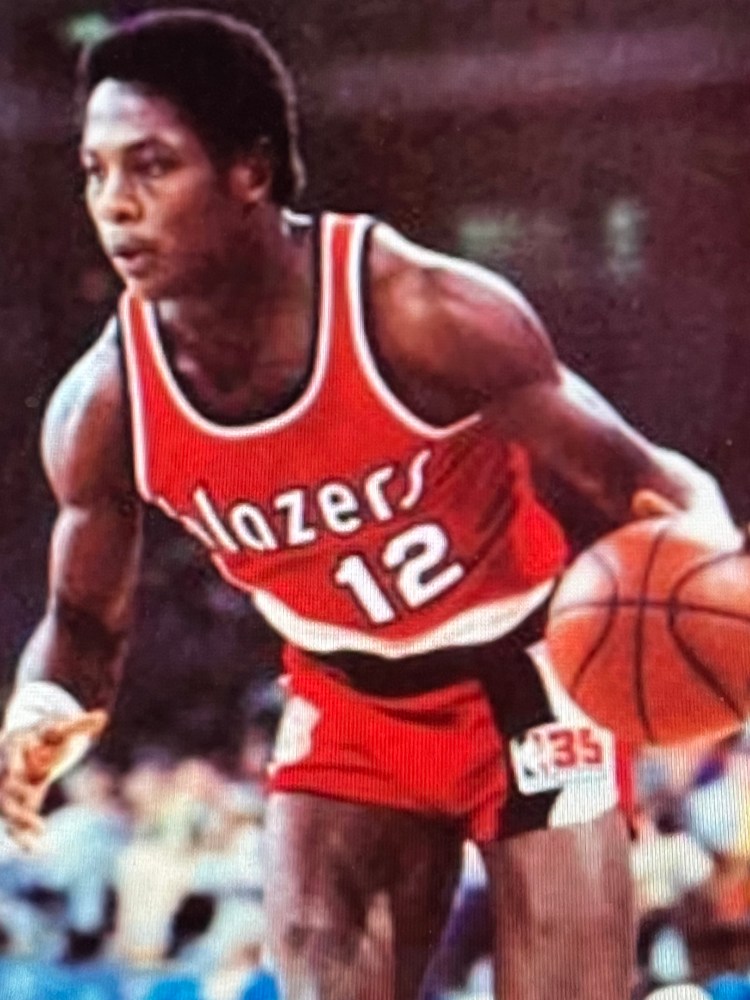

Late in the winter of 1980, the Blazers were a team struggling to remain in the playoff hunt. Decimated by injuries, they looked to the fledgling Continental Basketball Association (CBA) for help and were titillated by a wildly talented, wildly undisciplined, barrel-chested guard from the Maine Lumberjacks. Even his name, Billy Ray Bates, was straight out of pulp fiction.

“I had seen him at a camp in Portsmouth and was immediately impressed,” recalls Bucky Buckwalter, now senior scouting consultant with the Blazers.

“Physically, he was just awesome. He was only 6-4 but was a great jumper, and he was so strong. He didn’t play for a big college program, and his game was rough around the edges. But Stu Inman [then general manager] and I really wanted to take a chance on him.”

On paper, Bates and the Blazers were, to put it charitably, a precarious match. Bates was an improvisational player who never had a decent coach and never learned fundamental team basketball. The Blazers, meanwhile, were coached by Jack Ramsay, a man faithfully wedded to structure and a playbook so heavy it could give lesser players a hernia. But Ramsay knew his team needed a jumpstart. He agreed to give the kid a shot.

When the Blazers offered Bates a 10-day contract, they had little idea they were about to open one of the most exciting and intriguing chapters in the franchise history. Bated joined the club on February 23, 1980, his reputation as an eccentric, Marvin “Bad News” Barnes-type apparently having preceded him. “One of my first memories as a Blazer was meeting Bill Walton in an elevator in New York after I just joined the team,” Bates says. “I looked at him and said, ‘Hey, Big Red, I’m Billy Ray Bates.’ He just looked at me and started to laugh. I guess he heard I was a pretty funny guy, which I still am.”

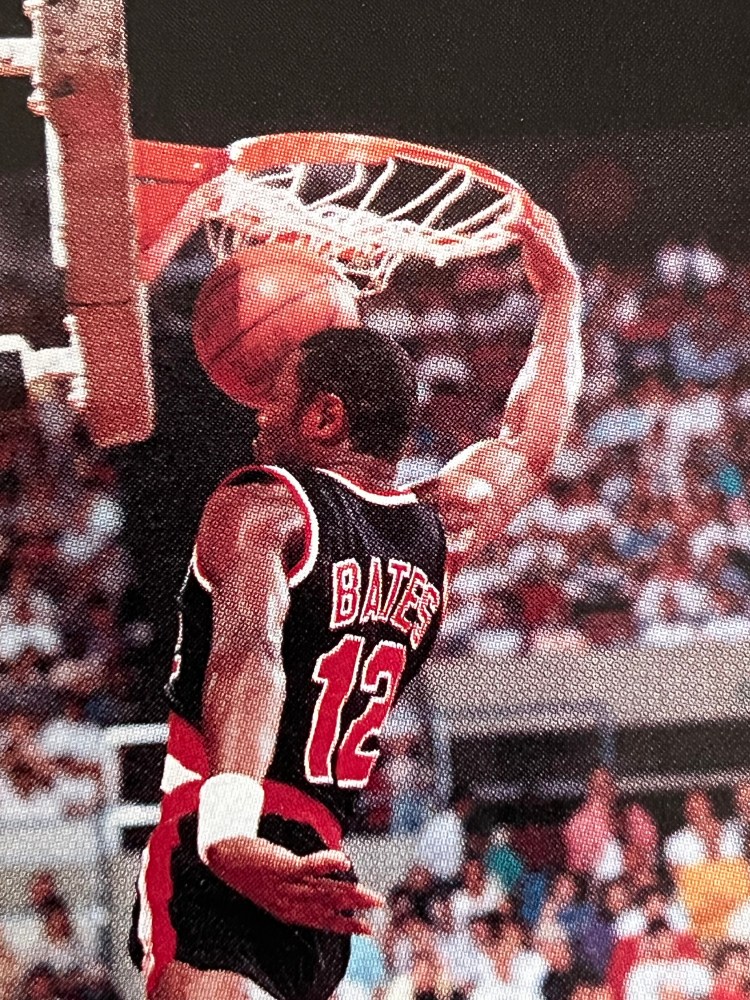

With some initial reluctance, Ramsay let Bates loose on the court. The 23-year-old rookie and two-time NBA reject made the most of his chance. With muscles bulging and legs built of coiled springs, Bates immediately took over and became the team’s most-potent offensive player, averaging nearly a point a minute. By March, after having been in the league for nary a month, Bates was voted NBA Player of the Week.

Concurrently, Bates was the catalyst in righting the Blazers’ ship, pumping life into the team with his electrifying dunks as well as his quirky personality. “Billy Ray was Michael Jordan before Michael Jordan,” says former teammate Mychal Thompson, now a Portland sports radio host. “He was Mr. Excitement, Mr. Slam Dunk, Mr. Instant Offense. He was like a comet that came out of nowhere.”

Bates magically salvaged an otherwise ho-hum season. “He was the reason we made the playoffs that season, plain and simple,” says Thompson. And Bates was even better in the postseason. Though the Blazers lost in the first round, Bates scored 25 points a game, then the highest postseason average in team history.

David Halberstam, whose classic book The Breaks of the Game chronicles the Blazers’ 1979-80 season, still smiles at the mention of Bates. “I’ll never forget the way Billy came in and just carried the team. He had such tremendous athletic ability that, once he got in the open court, you knew something exciting would happen. But most of all, I remember his sweetness. He had such a humanity to him.”

For all of the Bates’ mid-air poetry and last-second heroics, ultimately it was his endearing nature that made him a fan favorite and later a cult hero. After games, while the rest of the team headed to the locker room, Bates would stay on the Memorial Coliseum floor and sign autographs. Sometimes he even would put on an impromptu dunking exhibition. When he had satisfied every fan, he jetted to the press room, where he regaled reporters with spirited interviews.

“Billy was one of the nicest players you’ll ever hope to meet,” says Buckwalter. “He’d stay and sign an autograph for every kid. He’d not only talk to the media, but he’d engage anyone who just wanted to talk. Unfortunately, this quality didn’t always serve him well.”

The flamboyance, flare, and reckless abandon that Bates displayed night after night on the court carried over to his personal life. Bates was a cause célebre in Portland, but with that, he became a magnet for the unsavory, including drug dealers, eager to immerse themselves in the company of a celebrity.

“People felt at ease with me, because I am an easygoing guy,” he says. “But I was the kind of guy who never would say no. Everyone in Portland must have had my phone number, and people I didn’t even know would come up to me like we were friends from way back.”

Players perhaps are better equipped to deal with a meteoric rise to stardom today. But not a marginally literate 23-year-old from Kosotusko, Mississippi. Bates, who had trouble driving a dilapidated station wagon that the Blazers initially rented for him, suddenly cruised up and down Front Street in a souped-up BMW, bedecked himself in enough gold to make Mr. T jealous, and was—how to say it—a prodigious ladies’ man. But if basketball gave Bates money, women, and overnight fame, it also built for him an impervious wall of your irresponsibility.

“Basically, he was a big kid,” said Halberstam. “But to understand Billy Ray Bates, you really have to understand his background. A lot in the world was hard for him, coming from where he did. In many ways, he just didn’t have the tools to make it in a post-industrialized society.”

Indeed, based on the conditions of his childhood, one would think the Bates bio started in 1856, rather than 1956. Bates was the son of a sharecropper who worked the land on a white man’s immense estate. He and eight siblings shared a shack with no running water nor electricity. When Bates was seven, his father died. Shortly thereafter, Little Billy Ray earned extra money for the family picking cotton.

He recalls vividly the day he was six years old and first picked up a basketball. “My mother saved up some money and bought us a rubber ball. My brother and I had dug the hole and mounted the basket and everything and were so excited to play. I gave him the first shot, but we left a nail hanging out when we built the goal. So, my brother takes the first shot and hits the nail, and the ball bursts. We didn’t have enough money to buy another ball.”

Eventually, Bates got a new ball. “For as long as I can remember, I wanted to play in the NBA,” he says. “I used to listen to the NBA on the radio late at night. All I wanted to do was play basketball every day.” When Bates arrived at McAdams High ready to make the varsity team, he was greeted by signs with hateful racial expletives. “It was strange,” recalls Bates, “because I never had any prejudices.”

After the dust settled and the anti-integration racists switched schools, Bates stayed at McAdams, where he not only made the varsity but went on to be a star. After averaging “something like 40 points and 20 rebounds” his senior season, Bates earned a basketball scholarship to Kentucky State. There, he came within 15 credits of graduating, fairly remarkable given the fact he read on a third-grade level. Bates’ superior athleticism made him a standout on the basketball court; so long as that was the case, he seemed to pass his classes.

The Houston Rockets selected Bates in the fourth round of the 1978 NBA draft. Bates held out, so the Rockets cut him. From there, he bopped from tryout to tryout on the Eastern Seaboard and eventually found himself in Bangor, Maine, in the disorganized CBA. Bates was seemingly a million miles from both Mississippi and his NBA dream, but he didn’t show it. He played hard, braved, the cold, and—par for the course—was the fans’ favorite player. His coach half-jokingly suggested he run for mayor.

But when Portland called, Bates was all too happy to liberate himself from the minors. “I knew I didn’t belong in the CBA,” he says. “I was ready to show the world what I could do. I honestly felt that I had more athletic ability than any player in the world.”

It was probably this sheer physical ability alone that kept Bates in a Blazer’s uniform for more than two seasons. After spending the first summer of his life with money in his pocket, Bates “lost his spark and never regained it,” says Ramsay. Given the expectations he had set with his dazzling rookie performance, the 1980-81 campaign was a lackluster one for Bates. He averaged a respectable 13.8 points, but made inexplicable mental mistakes and rarely played well on the road. As if to tease the team, the fans, and himself, he was again unstoppable in the playoffs, averaging 28.3 points in three games.

Still, the Blazers brass were profoundly concerned about Bates—a concern that only intensified the following season. Bates was tentative and erratic on the court, a far cry from the dynamo who was drawing comparisons to Dr. J just two years earlier. And off the court, he was visibly depressed and uncharacteristically distant. It was common knowledge within the organization that Bates had a drug and alcohol problem. Twice, the Blazers checked him into rehab. Both times he wasn’t able to complete the programs.

“I didn’t ever have a drug problem,” Bates claims. “I tried it, but I didn’t like it. My biggest problem came from keeping the late hours. All that’s behind me now, though. Besides, the Blazers didn’t use me right. Everyone said the reason I got cut was because I didn’t know the plays, but I knew every single one.”

Ramsay disagrees. “The drugs and alcohol did him in. There was no question that he had immense talent, but you need more than that to make it in the NBA. He never really learned the plays or picked up on the team concept.”

On the eve of the 1982-83 season, the Blazers sent word to Bates in Mississippi, where he was tending to his ailing mother, that they had decided to cut him. Days later, his mother died. Bates had nowhere to turn. The blazing comet who briefly illuminated the basketball stratosphere was now fully faded and out of sight.

Following an uninspired stint with the Washington Bullets, Bates retreated to suburban Philadelphia in the throes of depression. “I got real down and came back here and just drank beer and barbecued all day long.” Soon, Bates was in rehab, this time at The Meadows in Arizona.

“When he was at The Meadows, a lot of what was going on was psychiatric,” says Don Leverthal, one of the few friends from Bates’ glory days who still keeps tabs on him. “Most guys are in there for six weeks. Billy was there for eight weeks and, when he left, they wanted him there for another four. They wanted to know where this guy was coming from. Billy is a beautiful person, but if there are 100 people in a room and one of them is a troublemaker, rest assured, Billy will find him.”

Barely a week out of The Meadows and in woeful playing shape, Bates signed a 10-day contract with the Lakers, a top team with a martinet of a coach named Pat Riley. Bates lasted four games. “I got the opportunity, but I wasn’t in the right spot at the right time,” says Bates in typically cryptic fashion. “The only thing I remember from the Lakers is that Kareem and Magic teased me a lot about my Jeri curl. Then they brought Steve Mix to replace me. Can you believe that? Steve Mix to replace the legendary Billy Ray Bates?”

His reputation for being a “headcase” all but solidified, Bates did what most players do who still have a little game left in their legs. He went overseas. The first stop was the Philippines. “I was Michael Jordan over there. They called me the Black Superman.” He even wore signature shoes that bore the Superman logo.

He next played in Switzerland before returning to the Philippines for two seasons. The U.S. Basketball League, Mexico, and Uruguay followed. Bates’ shtick transcended language and culture, and his rep in each stop was remarkably similar; he was a massive talent, unstoppable scorer, an instant fan favorite who wore out his welcome on account of his lifestyle.

In 1992, at the age of 36, Bates returned to Portland in hopes of getting a tryout. “After all I had done for that team, I thought they owed me another chance,” he says. “I honestly feel like they owe me a million dollars. A million-dollar contract for three years. Is that too much to ask?”

Bates is frustrated to the point of waxing irrational when he discusses the Blazers organization. Yes, he remembers with uncanny precision every minute detail of his career here—literally every basket he scored in a white, red, and black uniform—and still follows the team today. “I keep telling him to go back to Portland,” says Leventhal. “[In New Jersey], he’s just another guy, but people still remember him in Portland.” Indeed, Mychal Thompson claims that Bates is the second-most popular player in Blazers history behind Clyde Drexler.

Eventually, with nothing to cushion his post-basketball free fall, Bates moved back to the East Coast, where his life turned more dire. Having parted ways with his long-time agent and guardian angel Steve Kauffman (“Last time I talked to him, he threatened me,” Kauffman says), Bates took it upon himself to call every team in the league in hopes of getting a tryout. Not surprisingly, there were no takers. He eventually ran his phone bill up to $2,000 before the line got turned off.

****

Today, Bates does receive phone service, but the state of his finances is dubious at best. Where did the money go? Bates says he’s not sure, but in the course of our eight hours together, he casually mentioned waterbeds, stereos, and car payments he made for various “friends.” To add insult to financial injury, Bates is short of qualifying for an NBA pension by only about half a season’s worth of games, and he already squandered an annuity he was supposed to receive from the Blazers when he turned 45.

Curiously, there is no indication whatsoever that a former NBA player lives in this tastefully decorated apartment that Bates shares with his wife, Beverly, and her daughters, Markeesha and Yamnisse. It is too small, though, for the four of them to live in peace. “I’d like to move to a bigger place,” says Bates. “But right now, I’m in financial debt. The good Lord will look out for me, though, and we’ll be out of here soon enough.”

After sweet-talking a custodian to let us into a high school gym outside Sicklerville, Bates wasted little time showing why he still thinks he can play in the NBA. The most casual fan knows the absurdity of any NBA team taking a chance on a former player who last suited up when Michael Jordan still was in college. Yet watching Bates, now clad in an ill-fitting mesh jersey over a tattered Suns t-shirt, making three-pointer after three-pointer, bank-in baseline jumpers, and display a dazzling array of dunks, the dreamer in you, if only for an instant, can’t help but think what a great story it would be for him to return.

Word spread that an NBA legend was in the house, and before long a host of prepubescent Shaq wannabes peered into the gym. Bates invited them onto the court and challenged them to a game of “Roughouse.” Relishing the attention and clearly in his element among adulating kids, Bates tricky-dribbled and toyed with the gang of suburbanites whose shoes were more expensive than his. Finally, he finished them off with the most-improbable 30-footer off the glass. “Put a little backspin on it,” he says with a wink. “Just like my father told me.”

None of the New Jersey teenagers had the slightest idea who Billy Ray Bates was. No matter. By the game’s end, they each went over to shake his hand and invite him back. “Next week, same time,” he responded. “You bring some guys, and I’ll bring some guys; and we can go full court.” Same old Billy Ray.

After the gym cleared out Bates continued shooting, and his monologue wavered between self-delusion and self-hate. “I just want one more chance,” he said, as he effortlessly drained jump shots from every spot on the court. “The only player out there better than me right now is Jordan, and that’s only because he’s younger. In my prime, I could do all the stuff he did.” You’re never quite sure whether he’s serious or whether to laugh.

Eventually, however, the moments of clarity won out. “I had a chance, and I’m thankful for that. But I just got caught up in some things I shouldn’t have been caught up in. I’m just glad I’m clean. I haven’t done drugs or had a drink in five years. I’m a born-again Christian; I go to church every week, and it feels good. I just wish I had some money in my pocket.”

What’s next for Bates? He talks in vague terms about coaching and working on an autobiography. “I would love to go back to Portland,” he says. “But I’d have to find a job that pays at least $40,000.” When it’s suggested that Bates audition for the Harlem Globetrotters, he suddenly turns serious. “Do you think you can get me a tryout?” he asks. “All you have to do is talk and play basketball, two things I’m good at. Besides, I bet they pay pretty good.”

Even before the 1994 documentary Hoop Dreams laid bare the myth of deliverance through basketball, countless Americans offered their version of the “I coulda been a contender” speech. But what makes Bates’ saga so compelling is that he was a contender. He doesn’t have to use his imagination to envision the what-ifs; he need only pop the highlight tape the Blazers made for him into his VCR for confirmation.

As we sit on his couch and watch a series of ferocious slams and game-winning baskets, recapturing them with the help of the slo-mo button, Bates’ face is aglow. It’s only when announcer Bill Schonely talks about defenders with names like Roundfield. Kupchak, and Gervin does one realize how much time has elapsed since the glory days of Billy Ray Bates.