[Nate Archibald had a fantastic NBA career. But most people think of him today and remember his early days with the Royals. They think of “Nate the Skate” going one-on-one—and winning—so often on a losing team that he remains the only NBA player ever to lead the league in scoring and assists during the same season. All true. But there was always so much more to Archibald’s game than breaking down defenders and getting to the rim.

Toward the end of his career, Archibald showed exactly that running the point in Boston and winning an NBA title. This article, from the April 1982 issue of the magazine Sport World, tells Archibald’s story while healthy and sporting Celtic green. Telling the story is reporter Jack Clary of the Boston Globe.]

****

It was kind of funny when you stepped back and looked from a distance. There were all those big hulking guys standing around and waiting for a guy named Tiny to come in and take charge. But you don’t have to be on the NBA merry-go-round as long as Red Auerbach to know the biggest brutes in captivity can’t win if they don’t have someone to point them to the right spots.

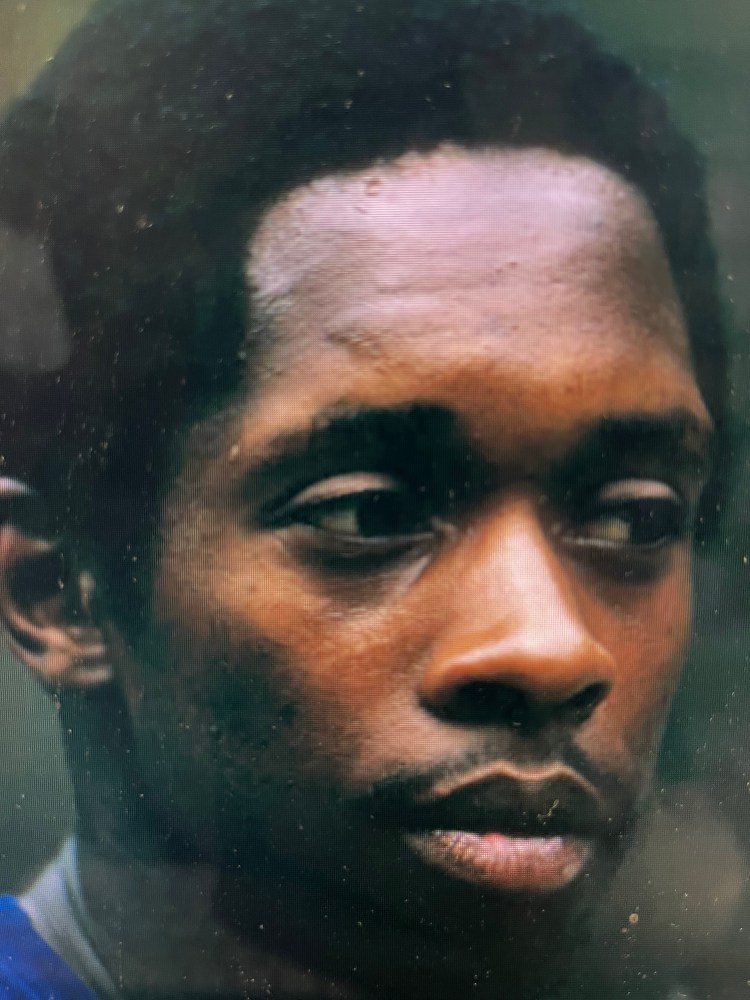

This is where Tiny Archibald, all 6-feet-1, has come to the fore since he joined the Boston Celtics for the 1978-79 season, last year becoming a driving—in every sense of the basketball term—force in the Celts’ 14th NBA title.

Though he is 33 years old, Archibald once more is the trigger that fires the bullet that becomes the Celtics’ famed fastbreak, one that can run-and-gun an opponent into merciless submission before he hardly knows what has happened. He is the classic example (along with Houston’s Calvin Murphy) that size of the body is not always equated with the size of the heart.

Archibald is the man who makes the Celtics’ offense go. He is the “penetrator,” the man who will get the ball and bring it into enemy territory, past the guards and into land supposedly dominated by the game’s giants. But those giants can’t stop what they can’t see or touch, and Archibald is like a little water bug as he skitters hither and thither, before shooting or dishing off the ball to Larry Bird, Robert Parish, or Cedric Maxwell, the Celtics’ frontline.

Some NBA teams labor for years without success, because they never have a player with those talents—one who can make things happen close to the basket. Some teams have been content to sit around the perimeter and patiently try to work the ball in toward the basket. If it happens fine; if not, they will try again the next time down the floor.

This has never has been the Celtics’ forte. Auerbach set the tone during his great coaching days when he demanded and got a flowing style of offense that went coast-to-coast with the ball, knowing it could score quicker than the enemy could regroup from offense to defense.

It takes someone to run this kind of offensive style, someone quick, who is both a good ballhandler and a good shooter. Auerbach had Bob Cousy for most of his glory years, then switched to Sam Jones when Cousy retired. In between, he’d bring in Frank Ramsey and John Havlicek, his famed “sixth men,” and the tempo would always race at the same quick beat.

When Jones retired, the Celtics continued to have some success with Jo Jo White in the role. But soon other deficiencies sapped this energy, and even White became discouraged and moved on.

As he tried to remake his dynasty, Auerbach never lost sight of the need to get a guard who could make things happen. But he had more serious problems trying to survive under the misery inflicted on his once-proud franchise by owner Irv Levin. He often acted without consulting Auerbach, his general manager, and brought in a succession of non-Celtic players, and the team slipped to the dungeons of the NBA.

Yet, after every rainstorm there’s always a rainbow. In one pure stroke of dumb luck, Levin and John Y. Brown, then the owner of the NBA’s Buffalo team that was being switched to San Diego, decided to swap franchises. Levin took the Buffalo team, and Brown became owner at Boston, along with his partner Harry Mangurian. Levin also took along many of the good players whom Auerbach had managed to accumulate through some shrewd trading. What Red got in return was a dismal array of talent that had bad reputations as one-dimensional, non-winning players.

Archibald was in that group. He had labored for years with the Royals, first in Cincinnati, later in Kansas City; then, with the New York Nets; and then to Buffalo, before coming to Boston. He had a reputation of being a fine scorer but doing little else. Tom Heinsohn, when he coached the Celtics, once remarked that Tiny “could give up 32 points on offense but give away 36 on defense, so you were [behind] even before the game began.”

Of course, that estimate was made in the context of who Archibald was playing with and the style of play that he had to endure. There is a little doubt that he still cannot be called a defensive giant, but he works at that phase of the game hard enough to at least stem the tide and direct the flow of the opposition’s offense toward the Celtics’ better defensive players.

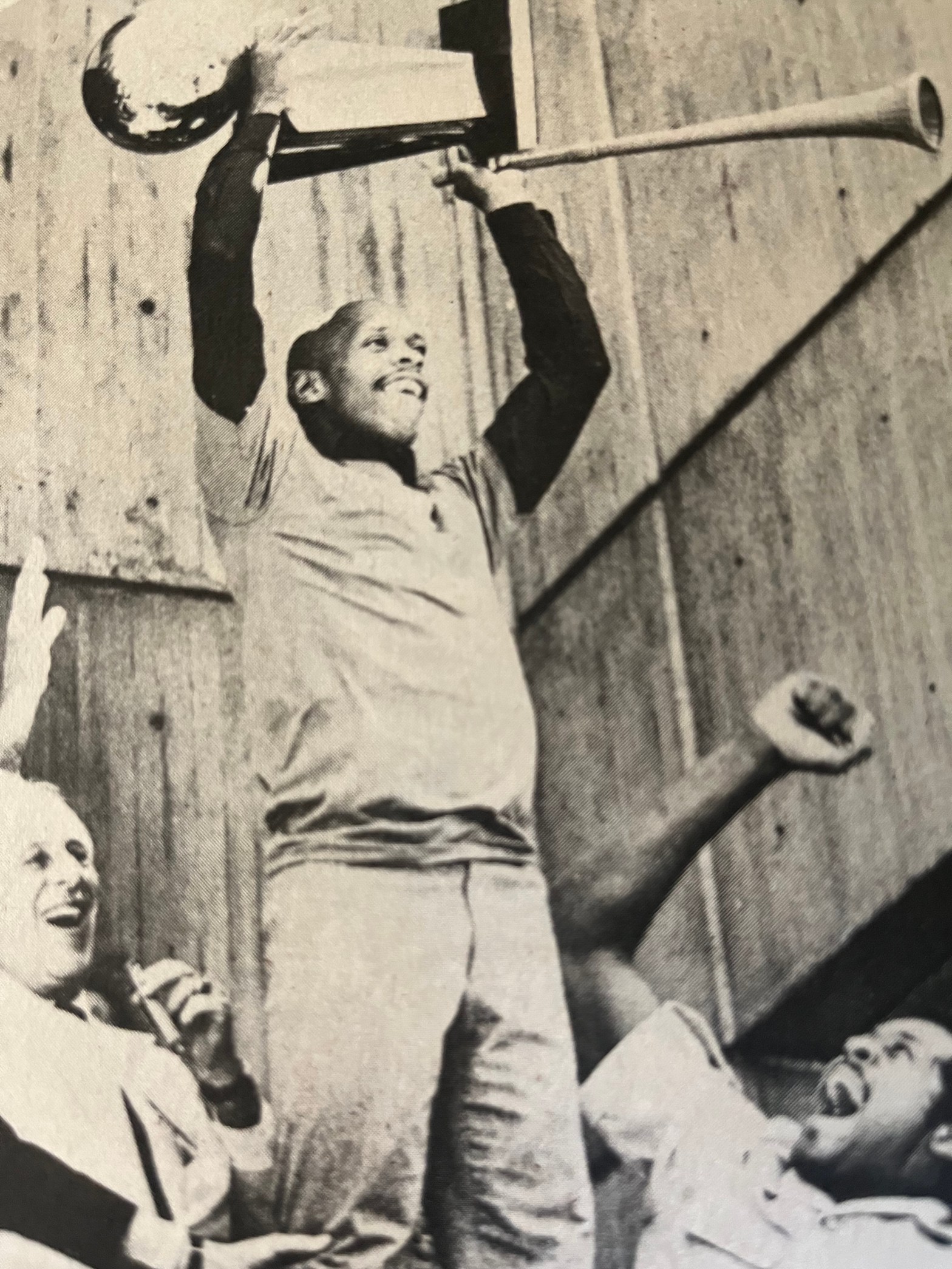

That is just one change in the life of this little man since his career was reborn in Boston. The biggest, in his mind, was at last being able to get his world championship ring after the Celtics had blown away the Houston Rockets in six games last year for the NBA title.

“Until that season, I had achieved most of the individual honors in pro basketball, and while I appreciate them, I wanted to win a title,” he says. “I felt we were close in 1980, but inexplicably we fell down totally in losing to Philadelphia in five games. That could have been discouraging for someone with a team that might be a once-in-a-lifetime playoff participant.

“But with the Celtics, I still felt we’d get back into the playoffs, and that I’d get another good shot. Well, it all happened, and I had my world championship. Now, I feel we can do it again, because the nucleus still is here if we can fight off other teams, which also are improving.”

Archibald knows all about that. He did some changing in his own right when he came to Boston and then had to integrate his talents into Bill Fitch’s style of play. Fitch, who became head coach at the start of the 1979-80 season, demanded more on both ends of the court.

Fitch also put great emphasis on “spreading around the word.” This meant that Archibald no longer could be expected to do it all. But it also meant that he was expected to fulfill his role precisely and with total energy.

Thought of as frail, he soon became a 48-minute player, leading the team in minutes played in his first season. Thought of as a freelance scorer, Archibald would go scoreless, but hand out a dozen or so assists, and the team won. Thought of as having lost a step at then age 31, he scored passels of points with his driving style and created defensive problems for the Celtics’ opponents.

“If you let it happen, this game will pass you by,” Archibald declares in looking at his different roles with the Celtics. “They gave me a challenge, and I had to meet it.”

Archibald now has the luxury of looking back on his career, at the various way stations and what he did and did not accomplish, even as he looks forward to the few years that he has left to build upon his recent achievements.

He maintains that his desire for a championship ring is not a case of simple hunger. Basketball is more than a job or business venture with him. During his previous NBA stops, he learned that the surrounding cast determined the overall success of any individual.

His lack of team success with the Kansas City Kings was mainly because he had to carry the scoring load. He could cite the same reasons for his dismal first year in Boston, too, along with the fact that while he sat more than he played, the turmoil of a franchise in trouble boiled around him.

“Winning a title is not a case of being hungry,’ he says. “It’s knowing your personnel and knowing the shape you’re in when the playoffs begin. When I thought we’d beat Philadelphia in 1980, I thought we’d also win it all because of all the experience we had on our team. But we fell in Philly, and that experience didn’t really mean too much.

“Last season, it was the same situation in that we had the best record and the homecourt advantage for the playoffs. But the added dimension for us was the new players who came to the team, like Kevin McHale and Robert Parish. The ingredients they brought to us helped us out more than the experience. And I don’t know if it’s the magic of the Celtics or not, but they do seem to find players who fit into their game style right away.”

The idea of fitting into a winning style is the one edge that has given Archibald his new basketball life. He astounded many by the fact that he could abandon his one-on-one type of play, or always wanting the ball to do the scoring, and become a total team player. “My role didn’t change from 1980 to 1981,” says Archibald. “I took a few more shots, but that’s all that I really changed. Mostly, I tried to stay with the gameplan.”

Archibald’s play the past two seasons reminds Cousy of the young rookie who broke in with the team in Cincinnati and then became better when the team moved to Kansas City. Cousy was the coach of those teams, and Archibald became the only player ever to lead the NBA in both scoring and assists the same year (1974-75).

The man whose opinions count the most is Fitch. He admits he wasn’t sure whether Archibald could play when he became head coach, because Tiny had missed so much playing time over the previous three seasons from problems with his Achilles tendons. “The toughest position for a guy to play for me is at point guard,” Fitch notes. “That’s because I expect him to be me.”

That means that the player must think like the coach, his alter-ego on the court, and that was totally new to Archibald. But he had made up his mind that he would make the adjustment, regardless of the cost, because he long had admired the Celtics’ type of player, and “I wanted to be considered as a leader.”

Fitch recalls that Archibald got into the spirit of his new job immediately. He ran the Boston break and soon had begun to accumulate 17 and 18 assist games. When other teams began to adjust to the fastbreak offense, he moved his game to the open areas opponents had left near the basket—the “back door” areas, where a quick, fast player such as Archibald can traverse the narrow spaces between the baseline and the area near the basket and do his scoring.

“There is only one Tiny,” Auerbach remarked time after time as Archibald became the team’s on-the-floor leader. “He can make the play. He’s the leader out there, and he’s exactly what we need.”

What helps Archibald in this continuing romance with basketball is his total dedication to the game. Every summer, he returns to the New York City playgrounds, where he first began to perfect his game. He doesn’t play basketball as much on the hot cement as he once did in the summertime (“I’m the commissioner now”), but he still organizes the teams and mingles freely with the players, helping here, teaching there, totally at home with his roots.

He also is totally at home with a new two-year contract that makes him one of the higher paid NBA players, and he fully expects to finish his career with the Celtics. He has tested the free-agent market, but with a touch of Celtics’ Pride under his belt, he never could bring himself to leave the Hub for more riches and less professional satisfaction.

That is one reason why he signed a one-year contract before the 1980-81 season was too old. That’s also why, before it ended, he had tacked two additional years to his Boston stay. “It was always Boston,” he says. “I knew what the team needed me for, and I came to do my best for my teammates.”

Now that he is onboard for at least two more seasons, there is a great feeling of well-being. That goes for the Celtics, who feel that his fragile legs can sustain their master for that time. That also goes for Archibald, who wishes to duplicate the success of last season at least one more time.

Down the road, the Celtics hope he will be around to tutor his successor, Danny Ainge, once the latter’s contract problems with the Toronto Blue Jays baseball team are resolved. Ainge still is the great hope of the future in Boston’ s backcourt, a player whose talents are a mirror of Archibald’s—he’s a penetrator, good shooter, developing playmaker, and probably can be a better defensive player because of his greater size.

“It would be a nice transition,” Auerbach says, noting that Archibald and Celtic guard Chris Ford are becoming greybeards at about the same time, and the team will have to come up with solid replacements.

“Tiny always has been the kind of player who is willing to help others,” he continued. “When we begin our transition, it would be fine if he could smooth it along with his own contributions in teaching and showing the new guys some of the tricks of the trade.”

Until that time, though, Auerbach fully expects that Archibald will be doing his usual job of directing traffic in the Celtics offense. He needn’t worry.

“There is one thing about this organization,” Archibald notes. “It has good people. Good owners, good management. It’s a family. Just look at the guys around the game who used to be Celtics. They’re coaches, general managers. A lot of things. I’m happy to be a part of it. Not only for now, when we’re still celebrating our championship, but also for the future.”