[This is a long post, so I’ll keep my comments brief. As many may remember, David Greenwood was the second pick in the 1979 NBA draft, right after Magic Johnson. The 6-feet-9, two-time UCLA All-American enjoyed a solid pro career that stretched into the early 1990s and brought him to several NBA teams. Everywhere Greenwood played, he was viewed as a great guy, great teammate. But, as this post highlights, Greenwood’s role as an NBA teammate would change over the years in ways that a former number two picks can ever imagine.

Let’s start with a quick introduction to Greenwood, two seasons after he entered the NBA with the Chicago Bulls. The article, written by reporter Alan Greenberg, was published on December 4, 1980 in the Los Angeles Times.]

****

David Greenwood, now employed by the Chicago Bulls, was in the stands at Pauley Pavilion

Saturday night when his alma mater played Notre Dame. It was his first time back as a non-participant, and he felt strange.

But only for a while. As the game wore on, Greenwood became more and more comfortable as he watched his successors dismantle Notre Dame the way UCLA teams have been dismantling opponents for nearly two decades. “You’re watching different guys running the same old offense, and it’s running the same old way,” Greenwood said. “And you say, ‘Wow, the old stuff keeps on working.’”

It worked so well that the Bruins did something Greenwood was never a party to during his three years as a starting forward: beat the Irish in Pauley. The next day, the Bulls were practicing at an empty Forum before playing the Lakers that night when someone told Greenwood it looked like UCLA didn’t miss him.

“I hope so,” Greenwood said. “That’s what it’s all about. I love UCLA, but it’s something I had to put behind me. You can’t live in the past. You put it up on the mantle, put it in the trophy case, and keep on going.”

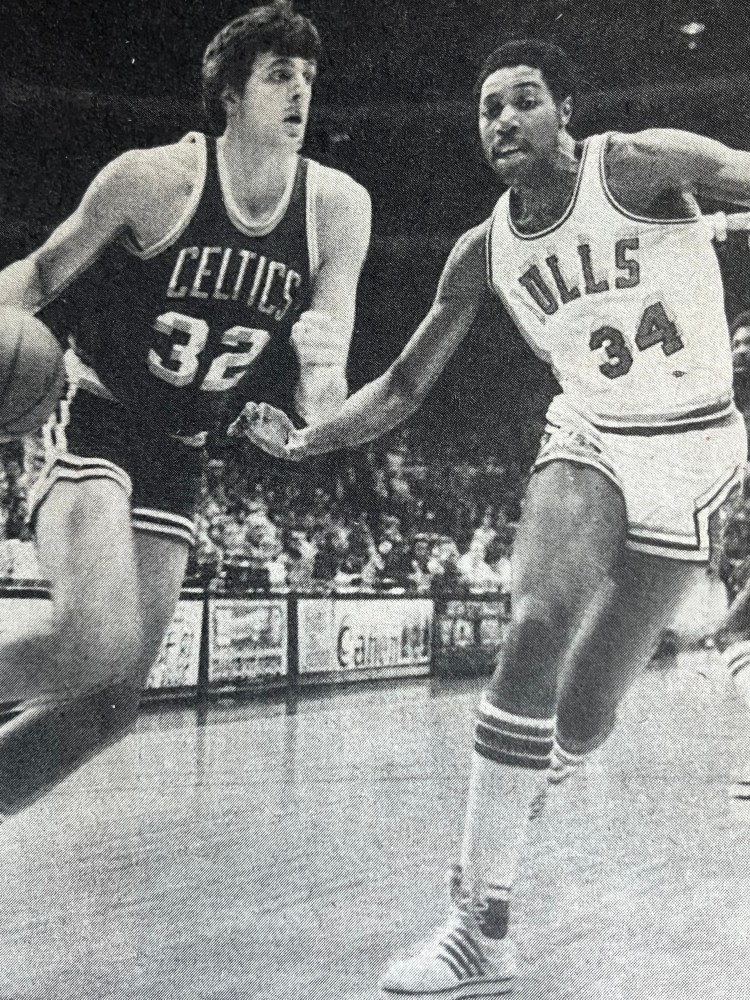

For Greenwood, the Bulls’ first-round draft choice in 1979 and a member of the National Basketball Association’s first-team All-Rookie squad, it is the only way. His entire career—and life—has been predicated on respecting authority, conforming to the system, and being a team player.

Consequently, Greenwood’s biggest problem in adjusting to the NBA has been learning to flout the rules. Schooled at L.A.’s Verbum Dei High School and UCLA to play with finesse and minimal contact, Greenwood—to his displeasure—soon realized that pushing and shoving were as much a part of the NBA as cramped plane rides and 6 a.m. wakeups. When it came to trickery and bending the rules, it was be good or be gone.

Especially at power forward, Greenwood was a greenhorn. But it didn’t take him long to understand why “Truck” is what everybody calls NBA power forward Leonard Robinson. “He was pushing and picking and shoving me,” Greenwood said, “and he had license to do it.”

So, the 6-feet-9 ½ , 230-pound Greenwood, after being bounced around by the likes of Robinson, Maurice Lucas, George McGinnis, and Elvin Hayes, got himself a learner’s permit. When in Rome . . .

“In college, you never got bruised,” Greenwood said. “You never went home from UCLA sore, stiff, and hurting.”

Now, he does. Sometimes, with his ears still ringing from opponents’ oral bullying. “The only shocking thing is this is the pros,” Greenwood said. “I didn’t know guys still tried to talk a good game to shake you.”

But he has adjusted and has started every game since joining the Bulls. After all, David Greenwood didn’t grow up on “Fantasy Island.” He grew up on the playgrounds of Watts and Compton, where he learned to survive.

But more importantly, he grew up one of five children in the home of Mr. and Mrs. Murphy Greenwood, where he learned to behave. Murphy Greenwood is a 6-feet-6 construction worker, and his wife, Johnnie, is 5-feet-10. They not only laid down the law, they enforced it. That meant church every Sunday, no smoking or drinking, being home by 11 on school nights—and no socializing until homework was finished. Parental permission was required to watch television.

Father Thomas James, now Verbum Dei’s principal, recalls that when he met Murphy Greenwood, his first instructions were, “If you have any trouble with David, you call me, and we’ll take care of it.”

Nobody ever called.

“David Greenwood,” Father James said, “is a model of what I’d like a student graduating from Verbum Dei to be. He wasn’t a basketball player in the senior class; he was a senior who played basketball.”

Bulls’ general manager Rod Thorn: “He’s a class human being . . . a pleasure to be around.”

Bulls’ coach Jerry Sloan: “They don’t come any better than David.”

Verbum Dei, a private school with an academic program as highly regarded as its basketball team, was tailor-made for Greenwood. Although he was All-CIF (California Interscholastic Federation), he shared the spotlight with his boyhood friend Roy Hamilton, a sharp-shooting guard, and a host of talented teammates. Greenwood never averaged more than 21 points a game, but Verbum Dei won two CIF titles while he was there. For him, that was reward enough.

When it came time to pick a college, Greenwood never seriously considered anywhere but UCLA. Being a vital cog in the Rolls-Royce of college basketball programs suited him fine. But not Reggie Theus, his friend since junior high and the star of Inglewood High. Theus, a 6-feet-7, third-year guard and Greenwood’s closest friend on the Bulls, chose the University of Nevada Las Vegas, a team with a run-and-gun, one-on-one style as gaudy as the town.

“I could have gone to UCLA,” Theus said. “But UCLA would have taken so much from me. I didn’t want to be toned down. David likes things to come to him, to be set up for him. But he’s a survivor. He gets along well with people. For him, UCLA was the perfect place.”

Although UCLA failed to win a national championship during Greenwood stay, he was twice a first-team All-American and developed the sound fundamentals and winning attitude that makes NBA general managers so covetous of UCLA players at drafting time.

In some ways, however, Greenwood believes UCLA hurt him nearly as much as it helped. For one thing, it made him such an unselfish player that Sloan and Thorn are always urging him to shoot more. For another, it didn’t prepare him for one constant in any NBA team’s 82 game schedule—losing.

“When we lost in college, guys were basically in tears,” Greenwood said. “People would look at us and say, ‘Crybabies, spoiled brats.’ We were. The way guys had their heads down, you’d have thought the H-bomb had dropped. All you ever did was win. Now, out in the real world, you see that nobody’s gonna win 84 straight. I still haven’t learned how to accept losing. I’ve just learned to deal with it.”

One thing that wasn’t easy to deal with was the arrival of forward Larry Kenon from the San Antonio Spurs. Greenwood, whose first inclination is still to pass rather than shoot, became so obsessed this season with getting Kenon in the offensive flow that he all but took himself out of it. Kenon, who only shoots the ball when he has it, was getting his points. But Greenwood, his favorite operating room inside clogged by Kenon and 7-feet-2 center Artis Gilmore, wasn’t, and the Bulls were suffering.

Things got so bad that Greenwood called up his cousin, Pittsburg Steelers defensive end L.C. Greenwood, for solace. “For 10 or 12 games this year, I’ve just been out on the court watching him, wondering, ‘How am I gonna play with this guy?’” Greenwood said. “For a long time, he was going east, and I was going west. Out here, you have to be a little selfish to be a superstar.”

Now things are better, and Greenwood’s per game scoring average is up to 14.3. Last season, he averaged 16.3 and led the Bulls in rebounds and blocked shots. Gilmore missed most of last season with a knee injury, and Greenwood was forced to play every frontcourt position. The Bulls’ best defensive forward, he is often assigned to guard the top NBA “small” forwards like the Bucks’ Marques Johnson.

“A lot of people thought David wasn’t physical enough to be a power forward,” Thorn said by phone from Chicago. “But he’s learning quick. We think he’s gonna be a great forward for the next 10 years.”

Greenwood was the second player picked in the 1979 NBA draft. The Bulls chose him after Thorn—heeding a straw vote of Chicago fans—called “tails” when NBA commissioner Lawrence O’Brien flipped a coin. It came up “heads,” and the Lakers, picking first, took Magic Johnson.

The Bulls got Greenwood. “A typical UCLA player,” Theus said. “He’s boring. He’s pretty standard.”

Greenwood is not about to forget who and what helped mold him. Verbum Dei has had a lot of outstanding players, but Greenwood is the first to stick in the pros. He already has made a donation to the school, taking the principal out to lunch, and given instructions that the transcript of his brother, Tracy, a Verbum Dei freshman, be forwarded to Chicago. Big brother is watching.

It doesn’t sound like the guy who called his mother long distance last year and a half joked, “I’m coming home, Mom. I don’t want to grow up.”

Greenwood not grown up? You decide.

“There’s always a player that’s gonna come in and do what you did and do it better,” Greenwood said after watching UCLA thrash the Irish. “And if you’re my kind of a person, you’re gonna hope that’s what happens.”

[By February 1984, the Bulls were ready to blow up its roster and start all over. That meant mostly trading away its high-scoring, ball-dominant star Reggie Theus, and Greenwood’s name came up in a couple of proposed multi-player swaps. All fell through. But the writing was now on the wall: Greenwood was expendable in Chicago. He may have been a class act, a top rebounder, and a good glue guy, but Greenwood would never be an NBA superstar.

Greenwood’s contract was up at the end of the season, and he wanted to test free agency in the early years of the salary cap. It blew up in his face. What follows is a brief article from the October 23, 1984 issue of the Chicago Tribune that shows how Greenwood, the class act, became Greenwood, the holdout. The story, written by the excellent Bob Sakamoto, also shows just how highly regarded he was as a teammate and team leader.]

One by one, the Bulls’ players drifted over to greet the familiar figure standing by the doorway of Angel Guardian gym Monday. They all seem to miss David Greenwood. “Yeah, they all call me on the phone and say, ‘Hey, man, when are you coming back?’” Greenwood said.

Orlando Woolridge, for one, can’t wait. While Greenwood is working out a new contract, the 6-feet-9 forward from Notre Dame has had more than his accustomed share of inside jobs. Life in the paint just doesn’t agree with this finesse player.

When Rod Higgins wandered over, Greenwood squeezed one of Higgins’ muscular shoulders and said, “You’re going to be a power forward.” Higgins smiled and bowed his head, mumbling something about how nobody could replace Greenwood.

Indeed, the Bulls’ captain has led the team in rebounding the last two years and was ninth in the National Basketball Association last year, averaging 10.1 a game. Coach Kevin Loughery spends more time bemoaning the absence of Greenwood than talking about anything else.

Loughery knows the best way to compensate for his team’s weakness in outside shooting is to use the fastbreak. Rebounding is the key to a successful fastbreak. David Greenwood is the Bulls’ key rebounder.

None of this is lost on Bulls’ vice president of operations, Johnathan Kovler, who is negotiating with Greenwood’s agent, Larry Fleisher. “David Greenwood is very important to our team, and we’d like to have him,” Kovler said. “But this is going to take longer than we thought.”

Originally, the Bulls made an offer to Greenwood of about $2.1 million for three years, but Greenwood opted to test the free-agent market. When nothing came through, the Bulls’ offer came down to $450,000 a year. Greenwood is reportedly asking for more than $700,000. There are a number of quality players experiencing the same problem, including Phoenix’s Maurice Lucas, Utah’s Adrian Dantley, and Golden State’s Joe Barry Carroll. Apparently, the NBA’s new salary cap, which limits a team’s payroll, has slowed the movement and acquisition of players.

“David is asking to be the highest-paid player on the team,” said Kovler. “Our position is no.”

“They wanted David to sign for about half of what they originally offered,” said Fleisher. “I don’t know if they’re trying to punish him or what for not signing earlier. The chances of David signing with Chicago by opening day are bleak.”

Meanwhile, Greenwood was all set to report to training camp in the best shape of his career. He has lost 20 pounds and is down to 220 through a regimen of dieting, running, and lifting weights that began in June. His vertical leap has increased three inches, and he claims his strength is up 40 percent over last year. “I felt sluggish and heavy towards the end of last year,” said Greenwood. “I wasn’t as quick, and my blocked shots were down. I also could have gotten more rebounds.”

Crediting the three-times-a-week weight training sessions and his trimmed-down body, Greenwood said he can now reach the top of the square on the backboard with his jump. He is shooting 300 jump shots a day six times a week and said, when the call comes through, it will take him two weeks or less to be in playing shape.

“It is disappointing to be sitting out after working so hard all summer,” he said. “Hopefully, the Bulls and I can work out some kind of compromise.”

[The compromise came the next month when Greenwood accepted $1.7 million over three years. He returned to start of the Michael Jordan era in Chicago. “Look at these phone lines,” said GM Rod Thorn. “They’re all lit up like never before. Four year ago, the phone company told us we had an antiquated phone system, Michael Jordan proved them right.”

The Bulls needed another scorer to ease the load on Jordan, and Greenwood was back on the trade block. In October 1985, Chicago sent him to San Antonio for George Gervin. “I have no animosity towards anybody, no hard feelings,” Greenwood said upon getting the news. “I’ve been with them a long time. I will keep up with them in the newspapers to see what the guys are doing.” Now age 28 and starting all over again in a new organization, Greenwood would become typecast as a steady veteran who scrapped inside for rebounds, played tough defense, and was good for maybe eight points a game.

In January 1989, San Antonio shipped Greenwood and guard Darwin Cook to Denver for Calvin Natt and Jay Vincent. His minutes dropped to about 17 per game, but Greenwood kept his mouth shut and went along with the system. He tried free agency the next summer and got a bite from Detroit. Their power forward Rick Mahorn had been lost to Minnesota in the expansion draft, and Greenwood would fill his shoes. Instead, Greenwood helped fill the very end of the bench. Sportswriter Mitch Albom tells the tale in this lengthy article headlined Bench Buddies. It was published in the April 18, 1990 issue of the Detroit Free Press.]

“So where’s the popcorn?”

“Huh?”

“The popcorn. Don’t you know the rules?”

“Yeah. Any fan sitting in that seat has to buy us popcorn. And beer.”

“But . . . the game is going on!”

“That’s why we’re giving you till the fourth quarter.”

“Wait a minute . . . You guys eat during a game?”

“Of course.”

“When else?”

“Are you serious?”

“We’re serous.”

“And we’re hungry. Get going.”

****

Grab a sleeping bag. Fill the canteen. We are heading for the End of the Bench. It isn’t exactly The End of the World. It’s worse. Even Columbus never looked for the End of the Bench. If he did, this is what he would have found: Scott Hastings and David Greenwood ordering popcorn.

Not that they eat it. Oh, once, against the Knicks, Hastings, after countless nights of sitting, shoes tied, jacket on, never getting a look from the coaches, finally decided to sneak a handful. “And a minute later,” he says, “when the kernels were still back in my wisdom teeth and I’m trying to pick them out with my tongue, I hear a Chuck Daly yell, “SCOTT! SCOTT! GET BILL. GO GUARD PATRICK!”

“You must have panicked,” I say.

“Well, I was happy to get in. And athletes are pretty superstitious. So, we figured from now on, we should eat popcorn every game.”

“Right,” Greenwood says. “Popcorn. Good idea.”

Here are two men in a world they never made: They come out with the Pistons, night after night, race through layup lines . . . and sit. And sit. And sit. Occasionally, they get into the action, for a pass, or a free-throw, or two minutes’ worth of garbage time. “But basically,” they say, “our job is to get stiff for two hours.” They squirm, they scream at refs, they make up jokes, they check out the fan in the fourth row.

“Does it ever get so boring you run out of ideas?” I ask.

“The last Charlotte game,” Hastings says.

“Yeah,” Greenwood says, “I looked over, and you were all foggy-eyed. I yelled , “SCOTTIE! SNAP OUT OF IT!”

“Thanks, man,” Hastings says, shaking his head. “I almost lost it that night.”

Other stories have been written about the last guys on the bench. Usually, they carry quotes such as: “I’m ready if the coach needs me. I don’t mind waiting.” Very nice. Very sweet. Complete bull. This is the real story. A world where boredom is the enemy, where humor is essential, where a “hello” from the head coach is a special occasion. A world where you rush to catch the bus because it might leave without you. Sitting? Watching? Night after night, without breaking a sweat? Who in his right mind wants to be one of the last two players off the NBA bench? It’s grueling. It’s frustrating.

And after careful study, Hastings and Greenwood have concluded there is only one way to avoid going nuts.

Go nuts.

Dave & Scottie’s How to Avoid Boredom, Idea No. 87: Take a Lap

Hastings: We got a 20-second timeout down to a science.

Greenwood: Yeah. As soon as it’s called, we get up and try to circle the team while patting each of the guys on the butt—

Hastings: —and get back to our seats before the buzzer sounds.

Greenwood: One lap.

Hastings: One lap.

Greenwood: You can make it in just under 20 seconds.

Hastings: Of course, if you stop to say something, it takes longer.

Greenwood: Yeah. Usually, you can only say, “Good job,” and move on.

****

Now, let’s get something straight right from the start: Nothing Hastings and Greenwood do is meant to take away from the team. They root. They holler. They want to win just like the other guys. Why else would they go through all this sitting?

But, yes, there are times they scream obscenities at the ref for a bad call, and, then, the instant the ref turns their way, they spin their heads toward the stands and go, “Who said that?”

And, yes, there are times when, for want of something better to do during the game, they check what their wives are wearing: “Say, Dave, Joyce looks real good tonight.”

“Purple skirt. Got it for her last year.”

There is the little dance, they do to the warm-up song, You Can Call Me Al by Paul Simon (“Sort of a Temptations thing,” Hastings says.) And there are the discussions they get into with the fans, who often sit inches from their end of the bench. “This one time in Dallas, a woman got all upset over one of our players cursing,” Greenwood says. “So, Scottie decided to talk to her.”

“Yeah,” Hastings says. “I asked, ‘What is a dirty word really? I mean, aren’t all words basically clean?’”

“After a while, he convinced her.”

“Maybe I just confused her.”

Maybe these two should go on the road. Live from Detroit, it’s . . . ScottieWood! Well. Why not? Have you ever tried reaching the top of your profession—and then just watching? The distance between stardom and trivia is just a few yards on the NBA bench, but those few yards can feel like a black hole. It was into this breech that Greenwood, 32, and Hastings, 29, tumbled this season, one a former first-round draft pick with a long, solid career and sore knees; the other a stringy-haired veteran with a lanky body and Jay Leno’s sense of humor. Unlike many 11th and 12th men, they were not rookies, they were not kids all starry-eyed and “happy to be here.” No. They were veterans who knew better. They grew friendly. They grew close. Now they are Martin and Lewis.

Dave and Scottie Talk about Fear

Greenwood: Unlike some other bench guys, we never root for the starters to get in foul trouble.

Hastings: Yeah, because our biggest fear is that the starters will all foul out, and they’ll actually use Vinnie Johnson at power forward before they use us.

Greenwood: Who needs that kind of embarrassment?

Hastings: Really.

****

Of course, we might have seen this coming with Hastings. Wasn’t he the Atlanta Hawk who once slapped high-fives with owner Ted Turner after sinking a three-pointer? Wasn’t he the guy who wrote a column for the Miami Herald last year as a player for the expansion Heat? Didn’t he once suggest the Heat’s losing streak could be solved with three easy steps: 1) Keep working hard. 2) Pick a fight with every opponent averaging more than 20 points, 3) Trade for Magic Johnson, Michael Jordan, and Karl Malone.

Hastings, 6-feet-10, is a Huck Finn face stuck on a giant scarecrow body. If he can’t make you laugh, you’re medically dead. You could picture him in overalls, steering a raft down the Mississippi. Of course, he’d be playing Nintendo at the same time. What do you expect from a man who comes from Independence, Kan.?

They call guys like Hastings “free spirits”—usually right before they call them “free agents.” That’s what he was last July. After stints with New York, Atlanta, and Miami, he signed with the Pistons.

Greenwood came a few months later. He, too, was a free agent and was coveted by several teams. But, at 32, a new team wasn’t enough. He wanted a ring. Coming out of college, he was a star, second player taken in the entire 1979 draft. Unfortunately, the first was Magic Johnson, who went to Greenwood’s desired team, the Lakers. Greenwood went to Chicago. He suffered there until the arrival of a kid named Michael Jordan—then the Bulls traded him to San Antonio. He suffered their waiting for a kid named David Robinson—then the Spurs traded him to Denver. Timing? Do you want to talk timing? David Greenwood has the timing of the coyote in the Road Runner cartoons.

“I figured Detroit could use me, since they had just lost Rick Mahorn,” he says. So, he signed in October. A one-year deal. A slow training camp hampered him. Then the improved play of James Edwards, John Salley, and Dennis Rodman left little room for his 6-feet-10 presence.

Suddenly, the former hero of UCLA found himself the last seat on the Detroit bench. What? “I said to Scottie, ‘I’m not used to this, man. If you ever look over at me and see me losing it, you gotta help me, OK?’”

Scottie nodded OK. He knew just what to do.

Dave and Scottie’s How to Fight Boredom No. 128: Chew a Towel

Greenwood: Scottie has this thing during the game where he just chews the end of a towel until he can pull a string out between his teeth.

Hastings: I used to leave it hanging in there, just to hear people yell, “Hey, you got a string hanging from your mouth!”

Greenwood: Then, one day he started blowing them onto people.

Hastings: They’re just little threads. Sometimes, James Edwards will come over, and he’ll be all sweaty. I’ll blow one at him.

Greenwood: And it sticks.

Hastings: Yeah, it’s pretty cool.

****

Now, I know what you’re thinking. Goodness. All that money and so little work in these fellas are having . . . fun? Well, before you condemn it, remember that these fellows, despite their spots on the bench, are still better than 97 percent of the basketball players on the planet. That’s the crazy thing about the NBA. You take a guy who was king of his high school, prince of his college, and, suddenly, in the pros, he’s the mop-up man. “I don’t care if you’re Mr. Optimist of the world,” Hastings says, in a rare serious moment. “Nobody can sit there and watch his job being done by someone else and feel like he’s contributing.”

“I never used to think about bench guys when I was a starter,” Greenwood adds. “I’ve gained new respect. It’s one of the hardest things to do. I really believe guys sitting would give up some money for the chance to play.

“And garbage time doesn’t cut it. I’ll be honest with you. Going into a game with 30 seconds left and a 35-point lead—that’s not playing basketball. It’s almost like an insult. That’s like saying the guy ahead of you can’t last another 30 seconds, so you get in there. Heck. We have a better chance of getting injured coming in cold than the guys who were already playing.

“Garbage time is a lose-lose situation. If you play well, they say, ‘Aw, it was just against the other team’s scrubs.’ If you make a mistake, they say, ‘See? That’s why we can’t play him.’”

Hastings listens. He nods. “Last month, I went into a game with 12.8 seconds left and came out with 11.6 left.”

“Amazing,” Greenwood says.

“Yeah, I got what we call a trillion.”

A trillion?

“Yeah. That’s when the box score reads: ‘1 minute played, followed by a row of 0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0.’ I got lots of those.

A trillion?

Dave and Scottie Answer the Question: Who are We?

Greenwood: Honest now, Scottie, when was the last time a coach came up and said, “Hey, how you doing? How’s your wife and kids?”

Hastings: Never!

Greenwood: See? We do not exist.

Hastings: Right. We are like the twins that the family hides in the basement.

Greenwood: We are like professional blackboards; there’s nothing there.

Hastings: We are like the insurance policy that you get when you’re first married—

Greenwood:—and then you stick it in the attic—

Hastings: —and 40 years later, you dust it off and say, “HEY, HONEY, LOOK WHAT I FOUND! IT’S DAVE AND SCOTT!”

****

Which is not to say they are bitter. Oh, sure, they want to play. And maybe they wish the coach would feel what they feel. But they’re enthusiasm for teammates is almost legendary. Joe Dumars, during his recent injury, spent the first few games sitting amid the Hastings-Greenwood show. “You guys are too into it for me, man,” he said, finally, moving back uptown. “I can’t believe how much you yell!”

Often times, when a Piston is having a bad stretch, he will come to the bench and get an earful from Chuck Daly. Then he’ll wander to Hastings and Greenwood, who he knows have been watching. “James, you drove the baseline the last five times. Go to the middle next time,” they’ll whisper. “Salley, stop thinking so much and just go up with it . . .”

Often, the advice is good. And when the guys go out and sink a basket, they turn to Greenwood and Hastings and point and smile. Let’s face it. Sitting on the bench makes you a pretty keen observer. But, mostly, sitting on the bench just leave you sitting on the bench. Sometimes, even the jokes can be painful. There was a time when Hastings and Greenwood were giving a verbal lashing to referee Darrell Garretson. Finally, Garretson turned and said, “Hey, you getting in the game tonight, Greenwood?”

Ouch.

There was the time when Hastings was a few seconds late, getting back to the locker room. The Pistons have a tradition after every game of huddling together, putting their hands in, and giving a word of togetherness. By the time Hastings opened the door, it was finished. They had forgotten about him.

“That must have hurt,” I say.

“Yeah,” Hastings admits. “But me and Dave just put our hands together and went, ‘YeeeaaaAAH!’ You know, our own thing.

****

The truth is, it’s not easy, this life of understudy. It’s dull and it’s agonizing, and you always feel you should be doing more. Especially when you’ve put in your time in the league. But you can swallow life’s lemons or you can turn them into lemonade. Hastings and Greenwood go for the laughs.

“Guys on the team ask us why we’re cheering so much,” Greenwood says. “But I say, ‘Wait a minute. I didn’t sit on this bench all year so we can lose the championship! Are you kidding? Are you crazy? I WANT A RING!”

He turns to Hastings. “And he wants a Porsche 928.”

And on they go. If the Pistons do indeed repeat as NBA champions, their pine ride will have been worthwhile. If not, about all they have to show for this most unusual season—besides a lot of “trillions”—is their friendship. Actually, it’s one of the nicer things about the NBA.

“We have grown pretty close, haven’t we?” Greenwood says.

“Yeah,” Hastings echoes. “Of course, 10 years from now when Dave is living on the street somewhere in a cardboard box and I am living in Buckhead, Georgia, I don’t know if we’ll still reach out and touch each other . . .”

If you can’t join ‘em, joke ‘em. Live from Detroit, it’s ScottieWood! By the way, should you go to a Pistons game and sit alongside these two and they turn and ask you for the popcorn, you can take it from there. They’re only kidding.

Now, about the beer . . .

[Finally, take a look at this clip from June 12, 1990. The Pistons are chasing championship number two against Portland, and who does Chuck Daly summons in game three? Reporter Michelle Kaufman answers the question.]

David Greenwood would find it funny he’s getting backslaps and handshakes for his five rebound performance Sunday afternoon. As far as he’s concerned, he should have had eight. “It’s not a surprise that I can play basketball,” said Greenwood, who hadn’t played in 11 straight games before playing 13 minutes in Sunday’s 121-106 Pistons’ victory.

“It’s no secret that I can rebound. People have been telling Chuck (Daly) to go to me all year, but he’s an eight-player coach. He likes to go to those guys he’s been loyal to, and that’s fine. But I think it got to the point where he had to go to whoever can do the best job off the glass, so he gave me a chance. I was shocked.”

Greenwood replaced Bill Laimbeer with one minute left in the first quarter and stayed in the lineup until two minutes before halftime. Greenwood’s aggressiveness on the boards was especially timely because of Dennis Rodman’s injury. “David played superb,” Daly said. “I question why I haven’t used him more. I guess I’m not smart enough.”

Laimbeer said: “Greenwood came in and dominated. He kept getting us all these T-shirts and thanked us for getting to the NBA Finals. I think he ran out of patience with us and decided it was time to do it himself.”

Greenwood, not one to gripe publicly, admitted the season chewed away at his insides. “I feel like I only played in four games all year, counting Sunday,” he said. “Tell you the truth, most of the year I didn’t even feel like part of the team. I can go buy a ticket if I want to sit and watch a game. I can buy pompoms if I want to be a cheerleader.

“If I’m not really going to contribute, I’d rather not be there. I don’t mind coming off the bench. I know my days of 40 minutes are over. But if next training camp comes and I’m going to play the same role I did this year, there’s no chance I’ll be back. Definitely not. I can’t take it mentally.”

Greenwood isn’t used to sitting. He was selected by the Chicago Bulls with a second pick of the 1979 draft, behind Magic Johnson. He played 30.1 minutes per game the first 10 years of his career. This season, he averaged 5.5 minutes.

Were it not for Scott Hastings’ humor, Greenwood might not have made it this far. The two seldom-used Pistons spent many off-days together, running, working out, and talking. “I was losing it by the end of the season,” said Greenwood, who played in fewer regular-season games (37) than any other Piston on the playoff roster. “If it weren’t for Scottie, I’d have lost it completely. He really helped me through it. We developed a very special friendship.

Greenwood winked at Hastings from the court several times during Sunday’s game. His most memorable minutes were the three in which Hastings got called off the bench. Neither could remember another time when they played together in the first half of the game this season. It was the first NBA Finals game for both.

“Just last week, we both had a good practice, and Dave was saying he wished we could play in a game together,” said Hastings, an eight-year veteran. “It was kind of neat being in there together. Normally, it’s like us, the team, against them. But this time, it was us against them.”

Hastings said, playing in the game made the victory much more gratifying. “The whole time, we were telling the other guys, ‘Win us a ring, win us a ring,’” he said. “But now, we got to do something for ourselves, so if we win it, we know we were part of it. I can tell my grandchildren I played in an NBA Finals game, at crunch time, when it counted. That’s the ultimate.”

Greenwood won’t be satisfied if Sunday’s 13 minutes are the last that he plays this series. “Scottie and I have different perspectives,” he said. “Scottie sat on the bench most of his career, but I’m used to playing 30-plus minutes. I wasn’t nervous Sunday, because playing is the most natural thing in the world for me. Sitting on the bench is the hardest thing for me to do.”

How many minutes would Greenwood like per game? “I’d be perfectly satisfied with 15 to 25— that’s not greedy, is it?”

He’s thrilled the Pistons lead Portland, 2-1, but considers the season “bittersweet” and said it was the toughest year of his life. “This was the hardest time for me, period, including childhood, high school, and college,” he said. “It seems like my team this year won more games than I won in 10 years in the NBA, but I didn’t have much to do with it, so it’s not as much fun.”

His one wish is that he gets a ring for all his private agony. “Don’t get me wrong, I’m behind these guys 1,000 percent,” he said, smiling. “I want them to win it all. Anything less than a ring would be terrible. It really is the only thing that would salvage the season for me. If we don’t win it, my season’s been a total washout.”

[Greenwood got his ring in Detroit. He also got a final season back in San Antonio, where played in 63 games, averaging 16 minutes, 3.5 rebounds and 3.8 points per outing.]

Thanks for this – this was great!

Greenwood may not have played much but he came up with the “Hammertime” slogan the Pistons used and which is associated for that 1990 season. I’ll always remember him for it!

LikeLike